Similar Posts

Editorial note: This post is the first of a series of four which touch on the topic of “canonicity” in icon painting. The series consists of an expanded version of an article previously published in Serbian and in Russian. * The author, Todor Mitrović, is one of the foremost representatives of the icon painting revival in Serbia today. He is also professor of icon painting at the Academy of the Serbian Orthodox Church for Fine Arts and Conservation in Belgrade. For more information on Todor Mitrović’s work see the interview published by OAJ.

Canon as a Paradigm

Are those icons painted according to the canons? This inescapable question defines the very “artistic” identity of the contemporary iconographer. It sounds like something you might ask a building engineer: Is this building designed according to prescribed standards? (Otherwise, it will come crashing down on our heads…) If we reframe the metaphor in religious terms, it sounds like a typical Old Testament legalistic dilemma: is this (food) kosher or not? Considering the context that raises this question and the reactions to different types of answers, the question itself seems to deal solely with an exclusivist religious setting, applied—in this case—to the visual arts. It sounds as though the correct liturgical art will appear, almost magically, only if the prescribed recipe is followed to the letter, and if the traditional rules are scrupulously obeyed. Following this prescription, within the precisely defined religious setting, produces particular goods exclusively for the community. They are not forbidden for “those others” but their production and use are binding and strictly codified for “us”—defining an important aspect of “our” identity.

This is not a parody—at least not in predominantly Orthodox societies. “Canonical” icons done strictly by the prescriptions (carefully hidden from the public) became the magical commercial formula for the growth of peculiar icon-production companies. Their empty and soulless “artistic” products could be promoted as optimal devotional images and—at the same time—as optimal commercial objects because their quality is guaranteed by the (mysterious) rules, sealed by the authority of millennial tradition. In such a stable synergy of religion, economy and arts, everyone is inevitably satisfied. [1] The production process is reliable, stabile and cheap, because it does not burden painter with unnecessary dilemmas and decisions. [2] The person who commissions the icon is pleased, because the result is of attested quality for a reasonable price. [3] The Church authorities are satisfied, because these icons effectively express their deep concern for art. After all, who would not be happy to see the steady growth of artistic production that also closely follows deeply grounded ecclesiastical traditions?

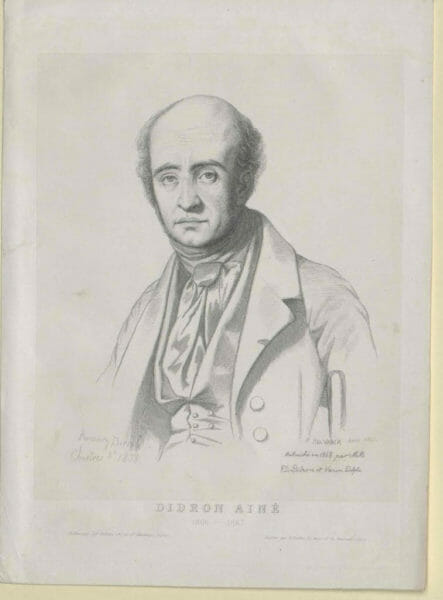

From the perspective of such a profound social consensus, the words of Adolphe Napoléon Didron, published way back in 1845, sound almost like a prophetic formula of the neo-Byzantine revival of ecclesiastical art. Let us then read the famous paragraph once again from this specific (contemporary) hermeneutic perspective:

The Greek painter is the slave of the theologian. His work is model for his successors, just as it is a copy of the works of his predecessors. The painter is bound by tradition as the animal is by instinct. He executes a figure as the swallow builds its nest, the bee its honeycomb. He is responsible for the execution alone, while invention and idea are the affair of his forefathers, the theologians, the Catholic Church.[i]

Adolphe Napoléon Didron (1806-1867), French archaeologist. Engraving published in Annales Archéologique, vol. 25 (1865), p. 376a.

Fortunately, art historians and theoreticians—in both East and West—have quickly moved beyond such one-sided and over-simplified categorizations, by developing cognitive tools to enable them to recognize Byzantine art as one among many of the highest artistic achievements of European culture. Unfortunately, on the other hand, a kind of invisible consensus—motivated by an understandable but irrational fear of losing the newly-re-discovered tradition—could turn the Orthodox Church into the devoted guardian of Didron’s “mantra,” thereby condemning the newborn art to become a pale shadow of the sublime heritage it was supposed to inherit. Finally, against the backdrop of those complicated circumstances, there is the impression that the end of the 20th and beginning of the 21st century have witnessed some important changes—both theological and artistic—in the reception and understanding of contemporary church art. This impression is precisely the motive for the following discussion.

Is there some different approach to the concept of canon and canonicity that could save us from this confusing consensus, which obviously does not sufficiently reflect what church art was in the Middle Ages, much less what it should be today? Perhaps the history of the term itself might inspire a hermeneutic approach. As Kittel’s New Testament theological Dictionary indicates, the appropriation of this ancient term by the Christians has been marked by interesting developments. In the New Testament, the word is used rarely. Only Saint Paul uses it in a specific way: “Paul uses kanṓn, though rarely, as a measure for assessing oneself or others. Thus, in Gal. 6:16, Christians have only the one “canon”; they see that all previous concepts and standards are set aside and they must now live by the new reality of the freedom that Christ gives. This will both determine their own conduct and enable them to see whether others truly belong to the Israel of God.”[ii] Later on, the term would gain more prominence, while its meaning would be adapted according to the changing ecclesiastical and cultural context. The entry continues: “Very early, disputes arose as to what was genuinely Christian. Hence, the Church was constantly forced to set up norms, e.g., for doctrine, for life, for accepting books as Scripture, for worship. It thus felt the need for a word that would unmistakably denote what is valid and binding in the Church. The terms κανών and κανονικός, which passed easily into Latin in their journey from East to West, seemed well adapted to this purpose. For the Roman Church, in particular, they took on decisive significance. (…) In the first three centuries, ὁ κανών served generally to emphasize what is an inner law and binding norm for Christianity. The term was hardly ever used in the plural.”[iii]

However, “after the 4th century, the general use was supplemented by the description of certain things in the church as κανών and κανονικός.” Canon, thus, becomes a terminological designator for “the collection of writings of the OT (…) and of the NT” or for “resolutions of Church councils.” These were later on “gathered in collections of canons” forming the basis for what would become the “ius canonicum.”[iv] Canon also became the designator for the catalogue of the clergy of a certain area— “to prove ordination and appointment to a specific office, all clergy were put on a list.”[v] From its genuinely generalized use, thus, the concept of canonicity shifted its semantic scope towards the juridical realm. The overall process of institutionalization which had struck the Church, after its perfusion by the Roman imperial power networks (in the fourth century), seems to have reshaped the term canon on its own. Thus, this generalized, abstract and internal norm of piety, Christian life, doctrine or worship,[vi] which would be closest to contemporary use of terms such as lore or tradition, was changed to the juridical form of list or catalogue, which is much closer to strictly formalized cognitive disciplines, such as law, logic or engineering. Now, why would this ancient paradigmatic change be important for the discussion of contemporary church art?

Notwithstanding 20th and 21st century theological developments, our contemporary church life is not governed by the kind of discipline characteristic of the early Church, but by the kind of discipline developed in imperial times. What we are dealing with today is obviously the semantic heritage of the post-Constantine concept of canonicity, quite akin to the legalistic discourse of a contemporary lawyer. However, it sounds quite odd, even a bit comical, in an artistic context. Of course, we can always say that icon painting is not just an art, since it is something more than that. However, is this mysterious “something more” that makes an icon so special in this confusing world—based primarily on some kind of list of rules? I doubt that anyone versed in this subject would be so naive as to answer this question in the affirmative. Nonetheless, I do not think the discussion about the (list of) rules can be closed by imposing such a question, either. Moreover, the reason for insisting on this discussion is the strong impression that the image of the list of icon-painting rules, however imaginary it might have been, hangs over the heads of contemporary iconographers, and radically defines the entire artistic production of the Orthodox Church.

To be continued…

*Todor Mitrović, “Сумрак канона: о потреби за одоцнелим језичким заокретом у црквеној уметности / Twilight of the Canon: On the Need for the Belated Linguistic Turn in Church Art”, THEOLOGY.NET: Theological Internet Magazine, March 29, 2019; Todor Mitrović, “КАНОН: ВРЕМЯ МЕНЯТЬ ПАРАДИГМУ. Почему концепция «языка церковного искусства» может стать альтернативой / Canon: Time to Change the Paradigm. Why the concept of ‘language of church art’ can be an alternative”, Gifts Almanac 5 (Moscow 2019), 14-27.

[i] Translation from: Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 1994, 18.

[ii] Hermann W. Beyer, “kanṓn,” in: Theological Dictionary of the New Testament: Abridged in One Volume (eds. Gerhard Kittel, Gerhard Friedrich), William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan 1985, 414 (only for this quote I used the Abridged in One Volume edition, since it gives a shorter formulation, more convenient for the purpose of this essay).

[iii] Hermann W. Beyer, “κανών,” in: Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, Vol. III (ed. Gerhard Kittel), William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1965, 600.

[iv] Ibid, 601.

[v] Ibid, 602.

[vi] “In three combinations it plays an increasingly significant role in the ancient Church: a. as ὁ κανών τῆς αληθείας ; b. as ὁ κανών τῆς πίστεως and c. as ὁ κανών τῆς ἐκκλησίας or ἐκκλησιαστικὸς κανών.” Ibid, 600.

Thanks for your efforts Todor. I know how all these questions are primal to many of the contemporary iconographers. All languages and all identities have both a coherent internal set of characteristics that afford us the capacity to recognize them for what they are, and they also contain a degree of variability which makes them living systems. Icon painting is no different than English or Science Fiction novels. It is as counter-productive to attempt reducing any living system of meaning to a set of rules and limits as it is to on the other hand to deconstruct these rules and limits by simply emphasizing their variability and showing exceptions. The first is the work of the obtuse legalist and the second is the work of the subversive divider. The former will stifle the system into paralysis, the second will deconstruct it into mixture and chaos. Having said that though, we also need those who point to the dangers of extreme variability because they have seen church iconography swallowed by modern paradigms of “art” in the 19th and 20th centuries. To think that cannot happen again is naive, especially as Christianity is under siege by secular philosophies. But we also need the intuition of artists who are integrating the language of iconography in a way that is alive and vibrant with particularity. I just wish the intuitive ones did not feel the need to attack the very tendency towards coherence, because if they do that, they run the risk of finishing their life as exceptions that have not been integrated into the greater system of meaning.

Thank you for your comment, Jonathan. I do agree that extremities are basically dangerous. Moreover, the idea of the integral article is how to overcome the extremities. Thus, next parts will speak about the rules and principles – may be a bit surprisingly – in quite an afirmative context :))

Todor thank you for starting this very important discussion. I personally agree that there is a problem. To find the correct solution though we must define the problem of contemporary iconography as accurately as we can. To ask the correct questions is fundamental to get the correct answers.

Would I correctly understand that you define the problem as a lack of personal artistic authenticity because a bunch of hidden external, juridical recipies are imposed on today’s iconographer?

In other words are you saying that personal authenticity is sacificed to achieve ecclesiastical – spiritual authenticity?

Your dialogue with Jonathan confused me even more. For Jonathan -and Jonathan please correct me If I misunderstood- personal authenticity is sacrificed to achieve a uniformity of the artistic language. Too much of the former destroys the latter….right Jonathan?

So is the balance we need now between personal expression and linquistic coherence? Because today we have the latter without the former?

Or is it about a balance of authenticity personal and ecclesiastical, because again today we have the latter without the former?

Can you please clarify? I want to be sure I understand you, correctly. Thanks.

Dear Dimitrios,

Thank you for joining the conversation with your excellent questions. I’m glad the article is beginning to stimulate discussion. I just want to remind you and Jonathan that this post is just the first one of a series of four. So I think the questions you have will gradually be answered in the upcoming installments. Be assured that Todor has taken into consideration most, if not all, of the angles and concerns you and Jonathan have brought to the table. Thanks again for joining the conversation!