Similar Posts

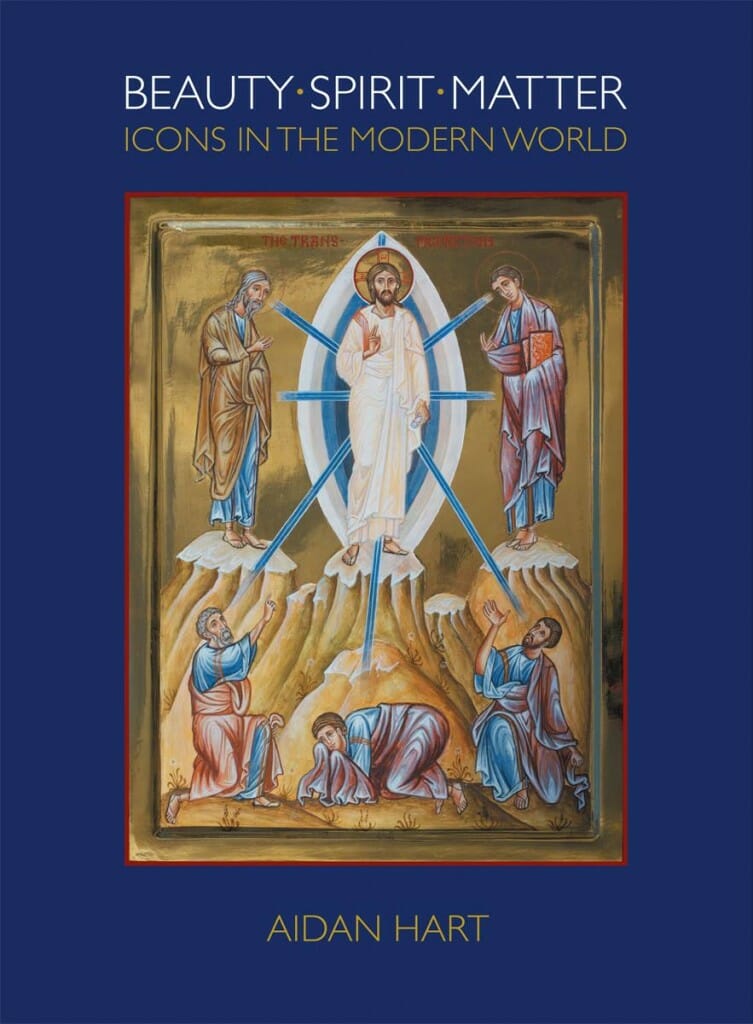

For the past 12 years or so, when perusing Aidan Hart’s essays and lectures, I often wondered if they would ever be published in book form. So it was a pleasant surprise to encounter some of them collected in Hart’s most recent book, Beauty-Spirit-Matter: Icons in the Modern World. It’s a long overdue book, bringing together in nine chapters the main themes scattered throughout his prolific writing. Whether Aidan Hart is talking about the icon, Tradition, ecology, beauty, the human person, scientific knowledge, contemporary culture, or modern art, the golden thread that joins the themes is the Orthodox teaching on deification: participation in the divine nature. Herein we find an aesthetics and theology of the icon that Aidan Hart elucidates in various ways throughout the book, using it to address some aspects of contemporary culture.

One of the main topics that Hart explores is how the doctrine of deification touches on questions surrounding ecology. St. Maximos the Confessor says: “For the Word of God and God wills always and in all things to accomplish the mystery of his embodiment.”(Ambigua 7) This mystery of “embodiment,” intended from “beyond the ages” as the destiny of man, is fulfilled in the Incarnation of the Logos, Jesus Christ, and actualized in us through our participation in Him in the sacramental life of the Church. Hart points out that the “embodiment” of the Logos pertains not only to man but also to the whole of the cosmos. Consequently, insofar as he fails to actualize his deification in Christ, man in turn abuses and desecrates the material world. In other words, an “ecological crisis” is inextricably tied to our failure, or our refusal, to become gods by adoption. Iconography then is not only relegated to the crafting of objects and images, but also to the personal struggle of acquiring the divine likeness- the art of reacquiring our paradisiacal beauty. Through the theology of the icon Hart then refutes the common accusations against Christianity as being a religion that disdains the body and condones the abuse of natural resources for selfish advantage.

Hart treats life in Christ and the salvation of man as an ontological, cosmic and personal unfolding of Beauty, arising from the mystery of divine embodiment. Beauty is first and foremost a name of God and therefore not merely based on subjective taste, what pleases the eye, or opinion. Rather, it has to do with ontology, the grounding of beings in their Source. A thing is beautiful in so far as it lives up to its intended purpose or nature. Therefore, in failing to live according to the truth of our being, grounded in the goodness of virtue through grace, in participation of the divine nature, we fail to become beautiful and impart beauty to Creation. Deification then is the acquisition of Beauty. The saints in their holiness are clothed with Beauty: “Oh worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness.”(Ps. 96:9 KJV) This “aesthetics” then is not limited to the classical “static” notion of beauty as symmetrical order, balance, measure, mathematical proportion and the like. Rather his is a more dynamic aesthetic that is personal, a process of actualization from glory to glory, taking into consideration relationship, communion in love, which iconizes the Holy Trinity.

When it comes to artistic practice, Hart discusses the copyist tendency in the current revival and calls for a more creative engagement with living Tradition as essential to renewal, pointing that there is much work to be done towards the founding of rigorous liturgical-art centers to further the training of iconographers.

Most Orthodox authors treating the question of modern art tend to limit themselves to scathing critiques. But in chapter 9, “Abstract art and the Icon,” Hart takes a refreshing, moderate approach to the question of modern art and abstraction. He points out that the pioneers of abstraction in fact were looking for an “art of essence.” That is to say, they, like the pioneers of the icon revival, wanted to go beyond naturalism, beyond the senses. In fact, they were looking for the logoi in Nature. Hart demonstrates this by extensive quotations, mainly Brancusi and Kandinsky, who came from an Orthodox background, and touching on other masters of modern art. However, he also points out the failures of modern art. He does this by contrasting it to traditional sacred art, describing its main features. Sacred art reflects man’s nostalgia for the paradisiacal life and his desire to unite with the Uncreated. Sacred art is mediatory, incarnational, a means of embodying the divine and making it accessible, immanent, palpable. Modern abstraction longed to accomplish something along these lines without Tradition, but in the end could only vaguely allude to a higher reality- it could not actualize our personal encounter with the Sacred.

Hart does not end on this seemingly bleak note, but suggests something further. He admits to the fact that “gallery art” is here to stay. Therefore he is not wholly pessimistic about the prospect of a “threshold art” arising from this fact, that is, an art that points to the Sacred and parallels the function of the icon and other forms of sacred art. As he puts it, “Gallery art as distinct from sacred or liturgical art is here to stay, and when at its best it enriches our lives. Though not art of the altar, it can function as art of the threshold, art of the atrium (the paradisiacal forecourt in front of the entrances to ancient churches).” (p.191)

“Abstract art and the Icon” would have been even stronger if Hart expanded on this observation, a challenging subject that touches on the role of Christianity as leaven in culture. If Orthodoxy has altered the course of cultures previously, imbuing them with newness of life, why can it not do so today, especially in the realm of non- liturgical art? I’m hopeful that Hart will elucidate this topic in the future.

At times historical in tone, then catechetical, devotional, even charming in his last chapter, Hart communicates with a simplicity that parallels the modesty of iconography. Perhaps in the not too distant future Hart will further discuss the question of “threshold art.” Although he touches on it here, he leaves the reader waiting for more. The book clearly demonstrates how the icon arises from the Tradition of the Orthodox Church, from the fullness of liturgical life in the Holy Spirit. Putting the icon within this context is very important today since as the icon becomes more and more popular the danger arises of treating it as an extra-ecclesial, activity, ironically ending up as another subjectivist “spirituality.” But in holding strongly to Tradition, as Hart shows and frequently cautions, we should not fear creative freedom within its parameters- true freedom that leads us to Beauty, in the life of the Spirit, and the transfiguration of matter.

Thank you, Fr. Silouan, for a fine review. I eagerly await Hart’s new book.

Excellent review, Fr. Silouan!

Moving along into a discussion of “threshold art,” given that it serves to enrich our lives and point us in the direction of the sacred (if not connect us to it directly) I suppose the discussion may get a bit subjective and non-academic right off the bat because what enriches my life might not enrich yours – you might find it offensive. We’re not going to have a canon of threshold art because one of the operating modes of this art is to overturn money-changing tables in the court temples, if you will. It makes us uncomfortable. I believe Chesterton said something like, “It is the peculiar call of the artist to remind us that we have each forgotten the name written on our deep heart.” And even when threshold art is not being provocative I suppose it is highly cultural and highly personal, which is good.

However, I would like to submit some names for your consideration of folks I believe operate in this threshold. Perhaps you will find something enriching for yourself, perhaps not. Those of you who are smarter than me can take this discussion back to academia if you want. I’m going dancing 🙂

Literature: Wendell Berry, Flannery O’Connor, Scott Cairns

Music: Sufjan Stevens, Arvo Pärt, CHVRCHES

Photography: Michael A Muller (http://www.michael-muller.com)

Painting: no comment for now. Peace.