Similar Posts

This post is the third part of a series. Part one: Mercy on the Right, Rigor on the Left, Part two: St-Peter on the Right, St-Paul on the Left

One of the aspects of Right/Left symbolism that is so usual in iconography it can almost go unnoticed is how Christ and the saints will be seen holding a book or scroll in their left hand, while blessing, pointing, showing, addressing with their right hand.

The most obvious image of this type is the Pantocrator, that image so common in Orthodox liturgical life. In this Icon, Christ is represented as the great Judge. With his right hand he blesses and in his left hand he holds a book, a book that is properly seen as the Gospels, but which can sometimes be interpreted as “the book of life” found in the book of Revelations.

The blessing gesture of Christ has a long history in Christian art, and it seems pretty clear it is a development of the Roman gesture of “address”, the gesture used in Roman art to denote that a figure is speaking. In fact, if we look at the earliest Christian art, we see how it is precisely this gesture Christ is making in those first images of him in a position of glory, of power or as a philosopher. In the same manner, the fact of holding a book or scroll in the left hand is usual in Roman art.

That a gesture of address would be transformed into a blessing should not surprise those who that have been following my articles on the left and right hand symbolism. Both the address and blessing suggest “directness” of influence. One can only receive a blessing from a person, not from a book, just as the notion of “logos” suggests the very act of speaking. The book on the other hand suggests the “roundabout”, the “indirect”, the fixed outer guard of law. It also suggests the “physicality” of law rather than the more “spiritual” logos. Here again we have the right hand as an image of the center, whereas the left hand is an image of periphery.

In order to understand this relationship of the left and right hands, we must never forget that the Pantocrator is an image of a Judge and a Ruler. His iconography became linked with Roman imperial typology because the Pantocrator is Christ as Lord of Lords. In this sense, one of the aspects of Right and Left in this image becomes the representation of the authority and power of Christ. Although authority and power have become almost interchangeable words in our times, in Roman and Medieval times they had a very distinct and meaningful complementary relationship. In fact, the idea of Auctoritas and Potestas was the basis of the entire Roman political system and adaptations of this distinction came to define both Byzantine and Western political relationships between the religious and temporal aspects of society.

In the old Roman system, the Senators represented the utmost in “auctoritas”, that is a capacity to influence based on who they were, their accomplishments, their social status, family history. Their capacity to influence was great, but it was not “executive”, it did not have the force of Law. This authority manifested itself by “speaking”, by influencing others through argument but also through your “clout”, who you were as a wise and experienced man with the appropriate status. In the image of the Emperor we have posted, the gesture of address is simultaneously interpreted by art historians as a gesture of authority.

The executive legal powers were given to magistrates and through other positions that could officially have laws ratified as well as apply and enforce them. This was viewed as “potestas”, that is power to transform the recommendations of the Senate into action. Potestas was linked to law, but also to military might through “imperium”, which was the ultimate form of potestas. Both legal and military powers contain a form of “applied power”, a form of exteriority. And here just as what we have said before, in the image of the Emperor Titus, the scrolls in his left hand is sometimes interpreted by historians as these “powers” that he holds. And since authority and power which were held separate in the Republic ultimately came to be united in the Roman Emperor, so too these powers came to be ultimately seen as originating in Christ who was the source of all authority and power.

We can get a sense of what we are discussing in the image of the Traditio Legis, an image type from early Christianity we have looked at in our post on Sts Peter and Paul. This image is of Christ giving the “New Law”. This is tradition in the strict sense of the word, that is a handing down, a transmission. In one version of this image, we have what is known as both the Traditio Clavius and the Traditio Legis , that is we see Christ giving the keys to St. Peter and the Law book to St. Paul. A thoughtful examination will show us that we have here a kind of extension of the Pantocrator image. On the right, Christ gives the capacity to bind and unbind, to open and close, this capacity is a “direct” power or rather an authority, the influence of blessing and cursing. On the other hand, the law book is the external power, it is the law in the sense we understand it today as a written code of rules and principles. The first is direct and linked to personal influence, while the second is indirect and linked to an external measure.

Notice the “remnants” of the Traditio Clavium and Legis in this 16th century Cretan icon St. Peter and St-Paul as pillars of the Church. St. Peter holds the keys and St. Paul holds a large book.

In the political sphere, with the advent of Christianity, this Roman understanding of authority and power soon morphed into an understanding of the Christian Roman Empire as having religious authority and temporal power, that is authority became more and more linked to spiritual influence. Although this took different facets in the East and West, in both cases these two aspects of influence became viewed as complementing each other, and this is the main meaning given to the two headed eagle, symbol used by both the Byzantine and later the Western Holy Roman emperors.

It seems therefore natural that, although speaking and blessing were always tightly related as a kind of direct influence, the “addressing” hand of Christ in Pantocrator typology became more explicitly a “blessing” hand just as “auctoritas” became more directly associated with religious authority and the sacramental reality it represented.

Double headed eagle from the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople. In its right claw, the eagle holds a cross, symbol of spiritual authority, in its left claw it holds a globe, symbol of temporal power. Here the two keys, rather than representing the “direct” influence as a whole, represent rather the power to “bind” from the right and “unbind” from the left.

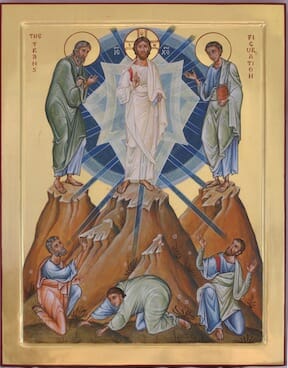

This play of authority and power is not only based on Roman institutions, rather we can see it in the Bible in the relation between the prophets and kings. The prophet’s authority is in his person, his holiness and is not bound by any external law (unlike the priests and Levites for example), yet the king receives his power through being anointed by the prophet and thus has the “right” to wield his power and to enforce law. This vision of the prophet as being the complement of law seems to be one of the reasons why in the icon of the transfiguration we have Elijah on the right of Christ as the prophet with direct influence, whereas we have Moses in his position of “receiver of the Law” on the left of Christ. (There is more to this placement in my opinion, but we can leave that for a future discussion).

Elijah on the right of Christ, and Moses holding the Law on the left of Christ. Transfiguration icon by Aidan Hart

There is yet more to the image of the Pantocrator, and how in this image Christ is shown a having both a left and right side, but we will leave this for our next installment relating to oral and written tradition. I am certain though that those who have been connecting the dots of the analogies I have been evoking can already trace the natural extension of the oral and written traditions as falling neatly on each side.

This post is the third part of a series. Part one: Mercy on the Right, Rigor on the Left, Part two: St-Peter on the Right, St-Paul on the Left

[…] https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/authority-on-the-right-power-on-the-left/Wednesday, Feb 27th 9:00 amclick to expand… […]