Similar Posts

To anyone who thinks that the Lives of the Saints have little practical application to our everyday life, I humbly beg to differ. To prove my point, I would like to offer some personal reflections on the new Russian film Leviathan, a film that would seem to be almost irredeemably bleak. But if considered in the light of the lives of holy fools, a very interesting picture emerges.

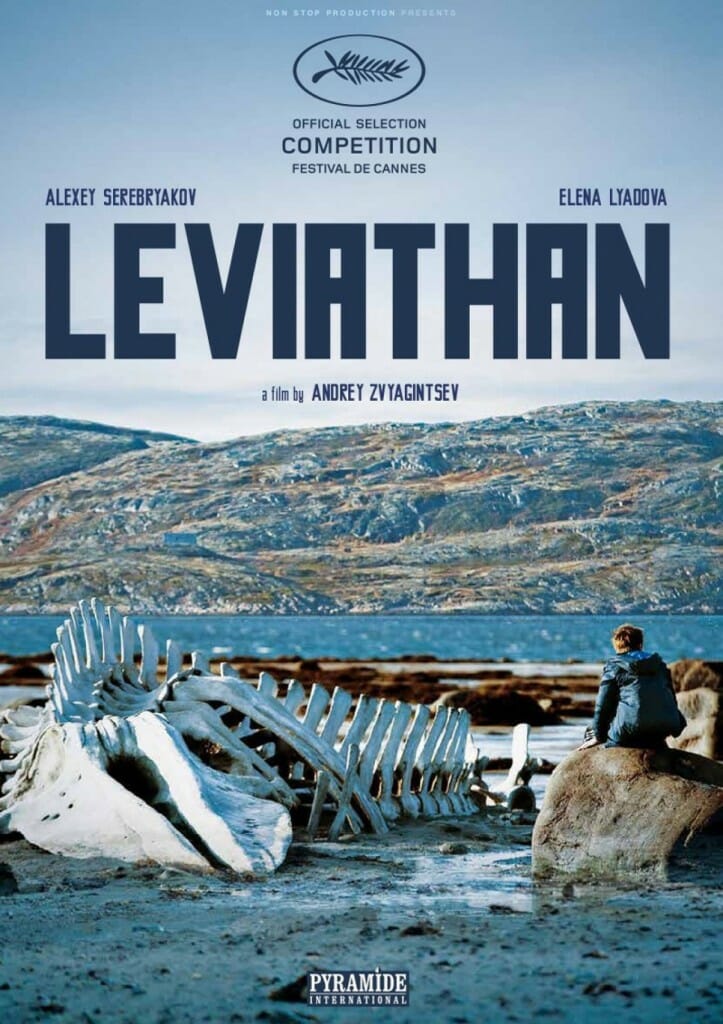

Although it has yet to make a ripple with American audiences, Leviathan is already causing a furor in Russia. Andrey Zvyagintsev’s fourth film, Leviathan is by turns beautiful, horrifying, ugly, depressing, and ultimately unforgettable. It is an extremely difficult film to watch, not only because of the obvious—profanity, nudity, alcohol abuse so pervasive it’s nearly comical (except it’s horrifying)—but because Zvyagintsev uncovers festering wounds in human nature that can leave no honest viewer complacent.

Most western media outlets focus on the externals of the story, especially on the “Putin-like” corrupt politician’s use of force against a local man named Nikolai and his big-shot Moscow lawyer, merely because he craves the land that Nikolai’s house is situated on, ostensibly to build himself a mansion. These reviews immediately assume that the Leviathan of the title—a reference to the Book of Job—is the irrepressible might of corrupt government as it crushes the defenseless citizen like an ant. And of course, to some degree, it is. But countless details in the film, and the final scene especially, suggests an entirely different interpretation, one that makes this film nothing less than a horror movie for any who call themselves Christian.

Here is why: the Leviathan of the title is actually, shockingly, the local administration of the Russian Orthodox Church, as represented both by a village priest and the local metropolitan. When faced with the reality of total human suffering, the village priest can offer little comfort other than the insufficient phrase “the paths of God are mysterious,” as well as a completely wrong-headed interpretation of the Book of Job, suggesting it’s better not to agitate the great beast Leviathan, lest he devour you. The metropolitan, next to the nuanced characters surrounding him, is little more than a cardboard villain until the last scene, when his technically correct sermon about God being found “not in power, but in truth” reveals him to be the devil himself, parading in a bishop’s miter and speaking with a forked tongue from the ambo to the oblivious churchgoers.

So, it would seem that widespread denunciation of the film among Russian conservatives as “anti-clerical” and even “anti-Christian” is warranted. Except that at least one Russian metropolitan actually thanked the director for his “inspiring” film, and many others have rushed to defend it. I say, without reservation, that they are right to defend this film. It is not, contrary to one irate Russian protopriest, a work “tainted by ideology.” It is not, as many have complained, a film shot with Western audiences in mind, a pandering attempt to secure a foreign-language Oscar. Leviathan is a work of art, inviting serious reflection and questioning, but offering no easy answers to the most pressing question that we did not even know we should be asking,

The question is simple, asked several times by different characters in the film, both “good” and “bad”—although there really are no “good guys” in this film at all, to be honest—“Do you believe in God?” The question is always asked at inconvenient, but essential moments. No one is able to answer this question in the film. But that is the point.

The movie is, after all, not called Job, but Leviathan, and Leviathan is the most terrifying Old Testament conception of evil incarnate. The village priest is not able to answer the question. The metropolitan is not even aware of the necessity of the question, but not because he believes. Rather, it is because he does not worship Jesus Christ of the New Testament. He worships Leviathan. All the characters do, even though most do not know it. In a subtle bit of brilliant imagery, when the main character wrestles with a loss no less terrible than Job’s, he asks “Why, Lord?” But he is asking this question while looking at the open sea, the lair of Leviathan. And when, in the next scene, he asks the village priest: “Where is your all-merciful God?” the priest asks him: “what god do you pray to?” By this he inadvertently stumbles on the truth – that Nikolai has been actually praying to Leviathan, not the all-merciful God.

If I could distill the film’s “message” into one phrase, it would be from Scripture: “Look carefully then how you walk, not as unwise men but as wise, making the most of the time, because the days are evil.” (Ephesians 5:15) The days depicted in Leviathan truly are evil, because those who call themselves Christian have become the Pharisees of the Gospels, content in their knowledge of truth and their guaranteed access to God and salvation, but oblivious to the reality of horrifying human suffering. Zvyaginstev has just made the Grand Inquisitor into a Russian metropolitan.

All through the last scene of the film, as I grew more and more horrified at what was being revealed, I kept thinking about another Russian film set in the far North – Ostrov (The Island). To all the eloquent oratory of the Leviathan-bishop about how “we all have access to the truth and righteousness of God because we are all the Church,” the voice of the saintly fool Fr. Anatoly reminds him that our “good deeds stink to high heaven before the Lord.” Truly, all this film needs to make it transcendent is the appearance of a holy fool right in the middle of the sermon to pelt the bishop with nuts.

I refer to the life of St. Symeon the Holy Fool, who used to do all sorts of absurd, even “deviant” things, as Derek Krueger aptly said in his Symeon the Holy Fool. St. Symeon used to shock the “proper” Christians by extinguishing all light in the church during a service at the wrong time, by pulling a dead dog around on a leash, by defecating in the street, by throwing nuts at assembled churchgoers. However, his actions were entirely intentional, even if they seemed mad—to shake Christians out of their complacency and the inevitable result of their spiritual complacency—hypocrisy. If Zvyagintsev has the gumption to offer us a vision of what happens when Christians allow themselves to become a new generation of Pharisees, I only wish he had the wisdom to throw in a holy fool in the last scene to teach everyone the lesson they so desperately need to hear.

Alas, Zvyagintsev does not do this, instead content to let the viewer remain in a state of shock at the horrors he just witnessed. So I recommend the following. Whoever has the courage to watch this tour de force should watch Ostrov immediately afterward. Not merely to get a bad taste out of one’s mouth, but to remember the lessons of the holy fools. If all of us begin to think more as they did; if all of us begin to live a life of humility and repentance as Christ taught with word and deed, then there would be no reason for the horrors depicted in Leviathan, or at the very least, there would be an answer to the eternal questions it raises. In any case, I’m glad I watched Leviathan. It made me want to be a better Christian.

[…] The Two Russias : Leviathan and The Island […]

Yeah.

Friendly reminder to all:

The world doesn’t need hagiography; it needs contemporary living holy people.

The former is helpful, but not ultimately convincing as it will not have an air of authenticity in a climate that is devoid of living proofs that these are not fairy tales.

So c’mon, y’all!

I don’t agree. There are contemporary living holy people. However, without hagiography, they tend to appear as madmen or even deviants. Anyone who doesn’t know about the lives of the desert fathers will read Elder Ephraim’s biography of Elder Joseph (My Life with Elder Joseph), for example, and think that the whole thing is made up, there are so many encounters with demons in a style very reminiscent of hagiography. So, yeah, we need holy men, but we need hagiography just as much. See my next week’s post on why we shouldn’t be so quick to use the term “fairy tale” in a derogatory manner, by the way. Thanks for the comment!

But the world doesn’t read hagiography. Yes of course, hagiography is an integral part of the nurturing life in the Church. I’m being brash.

I really like your thought that hypocrisy is the inevitable result of complacency. Comfort -> Complacency -> Hypocrisy -> A. Urgent Need for Holy Fools / Saints / Prophets, or B. Rebellion of the Young Members of Christ’s Body.

I’m just saying.

Glad I gave you some ammo for next week’s article 🙂