Similar Posts

TODAY AND TOMORROW: PRINCIPLES IN THE TRAINING OF FUTURE ICONOGRAPHERS

by Aidan Hart

1. INTRODUCTION

In this article I discuss the training of iconographers, not primarily the practical ways that this can be achieved, but the more fundamental question of what sort of iconographers we are trying to train. Or to put the question another way: What constitutes a well painted icon? Icon schools and teachers are working blind if we do not first give deep consideration to the qualities that we wish to nurture in the works of our students.

The effective training of iconographers is a pressing and practical issue. As the number of Orthodox churches increases, both in the West and in traditionally Orthodox countries, more icons and wall paintings are required. Also, Roman Catholic and Anglican/Episcopalian churches and individuals are increasingly wanting icons.

But given this demand, churches will be filled with mediocre work if our training of iconographers is mediocre. Forward planning is needed. It takes many years to become a good painter. According to the master iconographer Archimandrite Zenon, 10,000 hours of practice are needed to become proficient.

So is a good icon simply an accurate copy of a past masterpiece, or are there timeless principles within which there is room for creativity and variation, both from artist to artist and from epoch to epoch? Or perhaps the formal qualities of an icon have little theological significance and it suffices that the image simply bears the name of its subject?

Icons fulfil many roles, but I would like to concentrate here on two main functions that can be summarized with the words communion and illumination. I will give particular consideration to the role of illumination because this has the most importance for the formal or stylistic qualities of icons, and therefore on the ability and training of the iconographer.

Most of the article will outline various qualities which I believe are fundamental to well made icons. Some of these are theological, some aesthetic, some practical.

I have arrived at this “list” through a combination of close observation of actual icons over the past thirty years that I have been a full time iconographer, and from my teaching – in particular the Diploma in Icon Painting that I run for The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts. I will attempt to relate these principles to the theology of the Church as expressed through her liturgical texts, the Scriptures and writings of the Fathers, and also to current debate among Orthodox thinkers.

To illustrate my points I have mostly chosen examples from contemporary iconographers, and especially from some of those who tried to go beyond mere copying.

Contemporary debate about icons

I will begin by outlining a debate current among some Orthodox writers regarding why icons tend to be painted the way they are, what distinguishes them stylistically from other paintings. It is an important debate since the outcome will affect the future of icon painting and the training of iconographers. Fr. Silouan Justiniano has already covered this subject admirably in his series of three articles in OAJ, “The Pictorial Metaphysics of the Icon”. Here, I will therefore only give a summary of the matter as it relates to our subject of training.

For the past century the most commonly held view, led by Pavel Florensky, Photis Kontoglou (1895-1865), and Leonid Ouspensky is that the stylistic abstractions found in traditional icons exist to indicate the transfigured world, and that this style is integral to what makes a traditional icon what it is.

Although patristic writings dwell not on the formal quality of icons but on the theological fact that the icon is holy because it depicts holy persons, these writers argued strongly that icons, to be worthy of the name, must reflect spiritual realities in their style or form. Much of their writing was therefore centred on developing what we might call a “mystagogy of style”. As Ouspensky wrote:

The historical reality alone, even when it is very precise, does not constitute an icon. Since the person depicted is a bearer of divine grace, the icon must portray his holiness to us. Otherwise, the icon would have no meaning.[2]

The Orthodox critics of this notion, for example Evan Freeman[3], Irina Gorbunova-Lomax[4], Julia Bridget-Hayes[5], and George Kordis [6]assert that since patristic or historical accounts make no reference to such a thing, this mystagogy of style is a non-Orthodox innovation. As Bridget-Hayes writes:

The equation of abstraction with spirituality is found nowhere in Byzantine and patristic sources but is rather a modern phenomenon.[7]

They remind us that the Church Fathers defended icons purely on the basis that they depict the visual reality of the person and inscribe their name, and did do not refer to any capacity of icons to indicate the inner spiritual state of their subject. As the Acts of the 7th Ecumenical Council state:

Therefore it is in this form, seen by men, that the holy Church of God depicts Christ, according to the tradition of the Holy Apostles and Fathers. She does not divide Christ, as they frivolously accuse her of doing. For as we have said many times, what the icon shares with the prototype is only the name, not what defines the prototype.[8]

The icon lacks a soul – something impossible to describe, for it is invisible. Thus if it is impossible for one to depict a soul – even though soul is created – how much more is it impossible for one to consider depicting, in a perceptible way, the incomprehensible and unfathomable divinity of the only-begotten Son? – unless one is totally out of his mind.[9]

In his paper, Freeman calls the iconology of Florensky, Kontoglou and Ouspensky an “essentialist” approach, because the latter assert that icons must indicate the essence of the subject and not just the visible aspect of the holy persons that they depict. He argues that this mystagogic approach therefore contains the error of the iconoclasts, who believed icons shared in the essence or nature of their prototypes, whereas in reality the iconodules asserted that the image is linked to its subject through likeness to its subject and not at all through identity of essence. An icon is wood and pigment, not flesh and blood.

The critics argue that essentialism in iconology stems not from Orthodox theology but from modernist western aesthetics and philosophy. Florensky, Ouspensky and Kontoglou were not reflecting an Orthodox tradition at all, they say, but in fact owed their approach to the western mind that they so vehemently criticized. A pioneer of this essentialist conception of abstraction was the German art historian Wilhelm Worringer, whose work Abstraktion und Einfühlung (“Abstraction and Empathy”), was published in 1908. Worringer argued that abstraction in art aims to:

…wrest the object of the external world out of its natural context, out of the unending flux of being, to purify it of all its dependence upon life, i.e. of everything about it that was arbitrary, to render it necessary and irrefragable, to approximate it to its absolute value.[10]

While most of these critics acknowledge that icons do and should have stylistic parameters and should not be naturalistic, they give reasons other than essentialist. Juliet Bridget-Hayes writes for example:

There are reasons for the abstraction used in Byzantine iconography, but as we will see, it has nothing to do with symbolizing Christ’s divinity and the deification of the saints. Rather it is what helps the icon achieve its function of making the persons depicted present in the same time and space as the viewer.[11]

And later in the same text:

The icon, for the Fathers, shows historical reality. It shows the persons and events (“feats and braveries”) that took place, it doesn’t describe their spiritual state.

According to Irina Gorbunova-Lomax, herself an iconographer and teacher, one practical outcome of what she considers the pseudo-spiritualisation of style is that it tends to hinder iconographers from studying form and other aesthetic principles, and thus it becomes an unwitting cloak for artistic ineptitude.

Father Silouan Justiniano’s three OAJ articles present I think a very well argued case for finding the best in both of these two schools of thought. Arguing against those who claim that Byzantine icons were not stylistically different from secular work, he shows by examples that Byzantines were in fact selective about what they took from their classical and Hellenistic heritage, leaving aside its overtly naturalistic trends whilst retaining its respect for basic laws of form and drapery.

Father Silouan also addresses the curious fact that the few Byzantine passages that do comment on the stylistic aspects of icons actually praise them for their life-likeness. They do not comment on any departure from Hellenistic naturalism, in the way that Florensky, Ouspensky and Kontoglou later did, let alone give a spiritual explanation for it. Father Silouan argues, I think persuasively, that the Byzantine concept of being “life-like” cannot be identified with its current associations of photographic verisimilitude. A degree of abstraction is in fact required to do justice to the life of the subject, who is not of course simply a body but is a union of matter and spirit. As he writes:

… reality itself consists of intelligible (noetos) and sensible (aisthetos) realms. These spheres of being are symbolically conveyed by abstraction and naturalism respectively.[12]

I would add that, according to a Greek scholar friend, a better translation of the original Greek would in fact not be “life-like” but “living”, “full of life”, “as though alive”. This being the case, the emphasis in the Byzantine texts is not on the image’s likeness to the saint but on how the image makes the saint come alive for the devout viewer.

So, while on the face of it the silence of the patristic writings seem to side with the critics of the mystagogic approach, the witness of actual icons tells us that they have consistently favoured a considerable degree of abstraction. The question is why.

Because this stylistic abstraction has been such a constant feature of liturgical images in Orthodox countries, reason tells us that this surely must be related in some way to their liturgical use and their subject matter. Just what the actual reason for this is what is being debated. And I do not think that this is a debate just for cleaned fingered academics. Active, paint-dirtied iconographers must engage in it if they are to execute their ministry with intelligence and understanding.

Icon as agent of union and of transformation

My personal view is that these critics of Florensky, Ouspensky and Kontoglou do have a point, and must be listened to. They are a corrective to an uncritical spiritualisation of every stylistic aspect of icons, and often of just one particular school.

But I also believe that in some aspects the critics have, by way of over-reaction, gone too much the other way, especially in neglecting the capacity of style to affect the way that we see things.

I believe that the icon acts in two respects. First, as a likeness it helps draw us into relationship with the holy persons depicted. This is the icon’s primary role. But secondly, through its formal or stylistic qualities an icon can also be a means of transforming the way we see things.

While the quote from the Seventh Ecumenical Council given above makes it clear that icons cannot depict invisible divine realities as such, the ancient witness of icons themselves show that icons through symbolism do indicate their existence. All icons of the transfiguration, for example, indicate Christ’s glory by painting a nimbus around Christ.

After all, the Church Fathers had no hesitation in writing about divine things, albeit in a very guarded and provisional way.

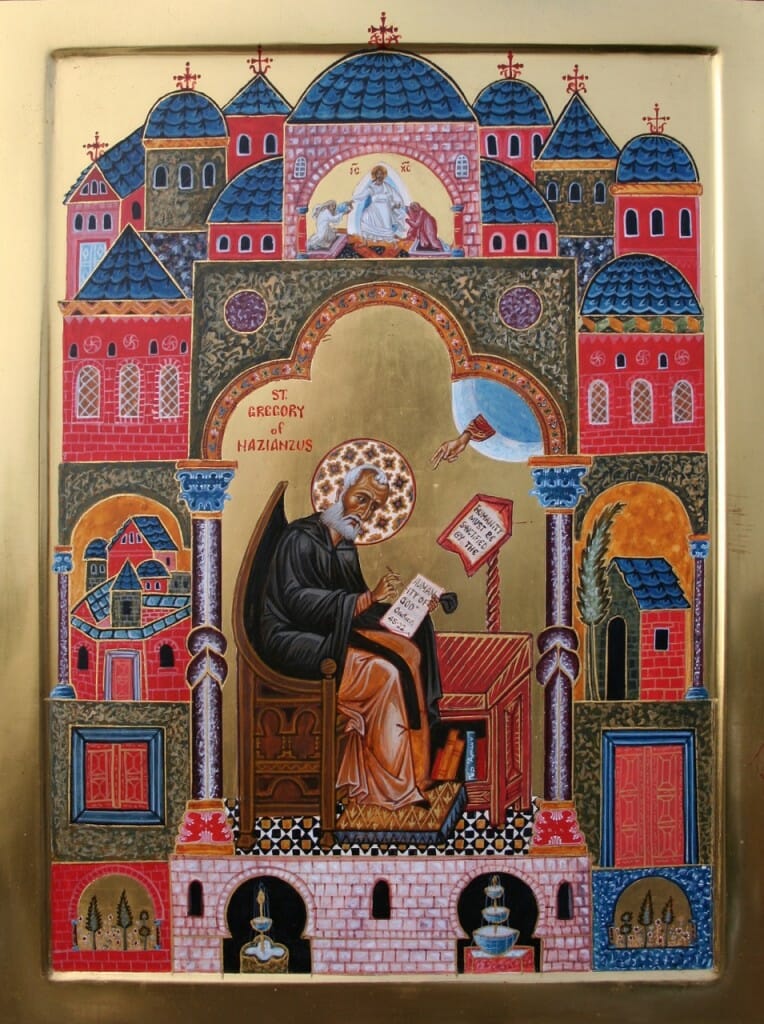

St Gregory Nazianzus and the Transfiguration (by the author). The Church Fathers wrote about divine invisible realities without thereby dishonouring them, and so in the same way icons can indicate their existence without claiming to encapsulate them (like the mandorla around Christ in icons of the Transfiguration which indicate uncreated light.

While they preferred apophatic terminology to katophatic – describing what God is not rather than what He is – we must remember that words are themselves a form of image, indicating things without claiming to be them. So if the Church Fathers believed that they could signify divine realities in words without thereby limiting or debasing those realities, then surely a painted image can do the same. Just as the great preachers and writers of the Church opened people’s hearts to their message through elevated oratory, so the painted image can do so by its elevated form.

The painted image invites us to see with the inner eye as well as with the outer eye. Abstraction can jolt us, awaken us from the slumber of familiarity with the material world as seen solely through the retina, and help us to see noetically. But more of this later.

Pioneers or corrupters? Apologists or compromisers?

If the form or style of icons can be transformative, why is this not written about in Byzantine texts? If the truth be known, we do not know why for sure. But perhaps the Byzantines did not feel the need to write much about this because it was taken for granted. The icon tradition was healthy and under no threat. Most patristic writing is after all a response to heresy or error rather than an attempt to codify theology for its own sake. To write about the formal elements of iconography had not been a requirement in the Byzantine epoch since, apart from the 120 years of iconoclasm, the icon tradition had remained effectively unchallenged and only tangentially in contact with post medieval western art. Iconography was Byzantium’s first language, her mother tongue, and it came naturally.

So why did people, such as Pavel Florensky, and then Photis Kontoglou, start writing about the way icons are painted? As icon painting returned to a more traditional style in the early decades of the 20th century, thinkers were needed to discern the theological differences behind these traditional icons and those of the previous three centuries which had been heavily influenced by western art. Part of this analysis was the need to develop an Orthodox response to the post medieval art of the West. Iconography in Ottoman Greece, and in Russia after Peter the Great, had been influenced by western art to a greater or lesser extent, most would say for the worse.

Our Lady of Kazan. Moscow, late 19th century. An example of the somewhat sentimental style that was common in 18th and 19th century Russia.

Our Lady of Vladimir, painted in Constantinople c.1120, cleaned 1918/1919. It was the cleaning of Medieval Russian icons such as this one and Andrei Rubliof’s of The Hospitality of Abraham in the second decade of the 20th century that helped revive traditional iconography.

The Mother of God contemplating a crucifix, Greece, 18th century. An Italian influenced work typical of icons painted in Greece from the 17th to early 20th century.

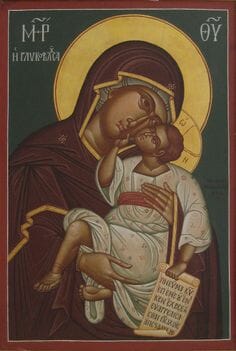

Virgin Glykophilousa, by Photios Kontoglou, 1955. The icons and writings of Kontoglou were a key factor in the revival of traditional iconography in Greece.

So, in quite a real sense pioneers such as Florensky, Ouspensky and Kontoglou were innovators in that they were treading new ground. And this was true in two respects. On the one hand they were in a similar position to that of the early Christian thinkers – the Apologists such as Justin Martyr – in that they were trying to discern what was usable in their surrounding culture, only of course their culture was the modern epoch and not the Hellenistic one of the Apologists. There were treading new ground because modernity was new.

On the other hand, while the Apologists were dealing with philosophies clearly described in written form, iconologists of our time are trying to understand the world-view behind the style of icons and other art. This interpretation of aesthetics from a theological point of view is a new discipline and therefore requires creative thinking, debate, and will inevitably meet with some excesses and disagreements. It is a work in progress and therefore requires both honesty and a forebearing spirit.

Perhaps inevitably, these pioneers sometimes reacted too strongly to non-iconographic art and became, to my mind at least, unnecessarily anti-Western in their polemic. Their writings often echo Tertullian’s cry, “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem? What concord is there between the Academy [of the philosophers] and the Church?”[13]

They could also sometimes be somewhat partisan. Kontoglou claimed that Byzantine icons were on a higher plane than Russian, and Ouspensky that the Moscow school was the summit of iconography.

To return now to our subject of training iconographers and what consists a well painted icon. For all the great things that have come out of studies on iconology over the past century, there have also been two unfortunate effects. Firstly, by way of reaction against untraditional innovations, there has been a tendency to associate tradition with the copying of old icons.

Secondly, the strong reaction against the naturalism of western art has too often meant that it is not deemed necessary for iconographers to obtain a good understanding of form, anatomy, drapery, proportion and colour theory. As the Romania sculptor Constantin Brancusi said, “Simplicity is complexity resolved”. Authentic abstraction in iconography must arise from a deep understanding of the form that it seeks to simplify.

To my mind the answer to the question of iconographic form must centre on the fact that Christ transfigures matter: He does not dematerialise it.

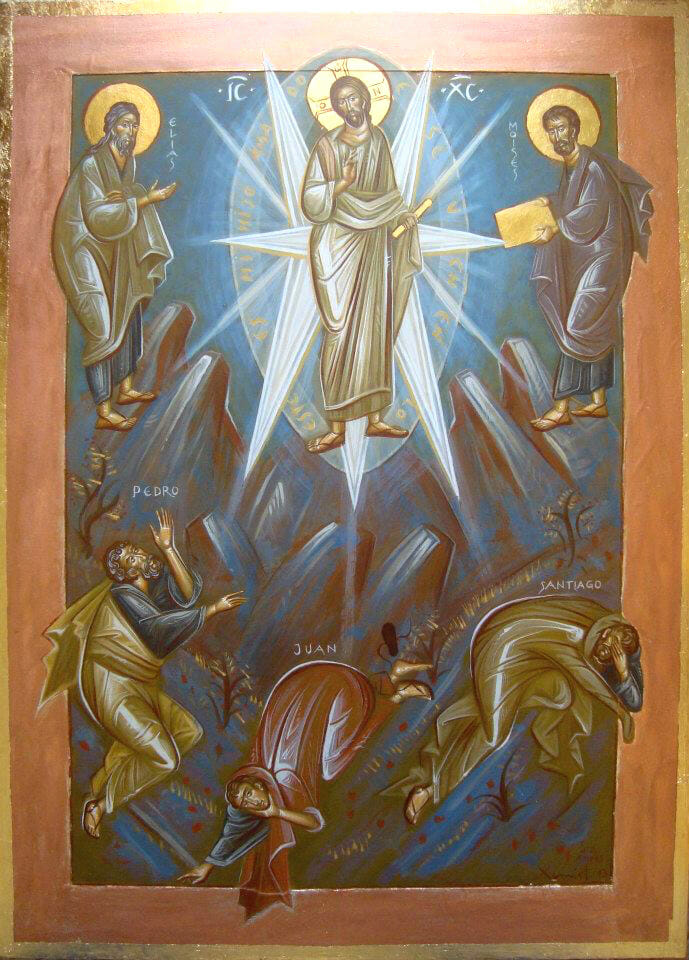

The Transfiguration, by Federico Jose Xamist, a Chilean iconographer. The Transfiguration of Christ expresses all the theology fundamental to the icon: the incarnation of God; the transfiguration of the created world; the communion of the saints.

So on the one hand icons must affirm the materiality of things. Icons can and should affirm form and matter, for this is part of the divine creation. We are not cardboard cut-outs. Every iconographer worthy of the name must therefore study and understand the form and colour of the material world.

On the other hand, icons equally show us a world in which this matter shines like Christ’s garment on Mount Tabor, transformed from mere matter to radiant adornment. So as well as understanding what is visible to the naked eye – creation’s form and colour – the iconographer must also learn how to abstract this visible reality so as to indicate its transfiguration.

2. TWO MAJOR ROLES OF ICONS

We shall now pass to an outline of the two major roles of icons. Let us remember also that iconography cannot be limited to painted panel icons, for wall painting, relief carving, mosaic, embroidery and so on are media also used to create holy images. Most of the principles described below apply also to these other media.

Icon as image

An image that bears the name and received likeness of the subject helps connect us with this subject – Christ, the Mother of God, the saints or angels. As the Acts of the Seventh Ecumenical Council put it:

For the honour which is paid to the image passes on to that which the image represents, and he who reveres the image reveres in it the subject represented.

This communion with the prototype is possible regardless of how well the icon is painted; even an unskilfully painted icon should be venerated, for we are venerating not the icon of itself but the holy person depicted. So this liturgical role of the icon as an object of veneration is primarily dependent upon what it depicts, not how it is depicted.

Icon as aid to illumination

But I believe that the icon has also a second role, which is to help us see the world not just as a bush, but as a bush burning with God’s glory without being consumed.

Moses and the burning bush. One task of the iconographer is to see and to help others see the whole creation transfigured, like the bush aflame with divine presence.

This role of illumination is more to do with how Icons depict their holy subject, with their formal or stylistic qualities. Although the divine glory cannot be depicted in its naked form, its existence can be hinted at through colour and line, through its embodiment in matter and holy persons. After all, light itself only becomes visible to us through reflection off surfaces. It would be to contradict patristic theology if we were to depict merely the outer aspect of things. As St Maximus the Confessor wrote:

…a view of the sensible world that relies exclusively on sense perception, are indeed scales, blinding the soul’s visionary faculty and preventing access to the pure Logos of Truth.[14]

St. Maximus the Confessor, painted by Archimandrite Zenon, one of the great iconographers of our times.

A traditional icon slightly abstracts the physical world in order to help us see deeper, to see the holy fire within all things, to awaken us. As we shall see later, the icon’s unusual way of depicting things throws us off balance in order to look for a deeper explanation. We recognize what we are looking at in the image – St Peter, St Paul, a tree, an historical scene or whatever – and yet the image is nevertheless different. The colours, the perspective, the abstract composition all suggest a deeper way of seeing than what our eyes and brain by themselves can see. They suggest the existence of ‘the pure Logos of Truth’ within. The icon affirms as real what we see and touch, but it also affirms as real the uncreated grace of God which creates, sustains and guides what we see and touch.

Saints Simeon and Daniel Stylites, by Thoma Chituc, Rumania. Chituc is part of a new generation of icon painters in Rumania who is helping to restore a freshness and vision to traditional iconography.

Even on the purely biological level we assimilate what we see in different ways. Indeed, as scientists tell us, we do not in fact see with our eyes at all, but with our brains. Electric impulses pass from our retina into our brains and it is there that an image is constructed, not in our eyes. The notions, expectations and experiences already recorded in our brains affect the way that it organises the electric data sent from our eyes. The brain is a synthesiser and not a blank slate.

We recall that the Fathers outline three phases of the spiritual life: purification; then illumination, in which we perceive the logoi or words of Christ within each thing; union, where we are deified or enter union with the Logos Himself.

The way icons are painted suggest all three of these phases, but I would suggest that the formal elements of icons are particularly relevant for the second phase: illumination. The word abstract means to draw out, and the abstraction of a good icon draws out and manifests the inner and unique logos of its subject, be it mountain, tree, animal or saint. I agree entirely with Bridget-Hayes and others who are against essentialism, but this is not to say that the existence of the inner logos or essence cannot be hinted by visual means.

As the iconodule Fathers were emphatic to point out, the icon is not of the same essence of the persons depicted, but connects with them through likeness to their person and by bearing their name. However, this likeness cannot be a mere matter of having two eyes and a nose, but must also be a likeness that suggests the subject’s particular virtues and ministry.

We could therefore say that the icon is not naturalistic, but it is profoundly realistic. It affirms both the materiality of the world and the fact that it is created, animated and directed by the Logos. The icon depicts the world as a tent of meeting over which the glory of the Lord hovers and through which He speaks. We recall the words of St Maximus the Confessor quoted above: “…a view of the sensible world that relies exclusively on sense perception, are indeed scales, blinding the soul’s visionary faculty and preventing access to the pure Logos of Truth.”

Icons are above all visual, and are therefore connected with the eye of the heart, what the Fathers call the nous. Words are good at instructing and explaining, at describing detail, whereas images are good at initiating us into a different way of seeing, and of giving us a unified vision of the whole. Indeed, St John of Damascus extols sight as “the noblest of senses”:

We use all our senses to produce worthy images of Him, and we sanctify the noblest of the senses, which is that of sight. For just as words edify the ear, so also the image stimulates the eye.[15]

This primacy of sight is surely linked with the primacy of the highest of human faculties, the nous. We recall the scripture’s description of the disciples’ meeting with Christ on the road to Emmaus:

As they talked and discussed these things with each other, Jesus himself came up and walked along with them; but they were kept from recognising him…Then their eyes were opened and they recognised him, and he disappeared from their sight. (Luke 24: 15,16, 31)

The words spoken between Jesus and the disciples prepared them, but the relationship was not complete until “their eyes were opened and they recognised him”.

Over the centuries Orthodox iconography has developed numerous ways of assisting this process of initiation or illumination. It is the task of an iconographer to learn these principles for they are his or her vocabulary. One of the most important works over the past century has been for iconographers and scholars to rediscover and disseminate both the timeless theological aims of icons and the many technical and aesthetic ways that iconographers can use to fulfil these aims. Among these ‘explorers’ is Dr. George Kordis, an influential iconographer, writer and teacher who is currently assistant professor in Iconography (Theory and Practice) at the University of Athens. Of these timeless principles he has written:

The immutability of Byzantine technique means that there has to be an artistic system with specific rules and principles governing the execution of icons throughout all periods of artistic trends; and, because such a system exists, it must be possible to discover and set out its principles. These principles obey an inner logic, and describing them is the first step stage in learning the art of icon painting. They can be described without endangering Byzantine iconographic style because they are constant and so unchanging.[16]

To these principles we shall turn in pt.2 of this study where I will illustrate them with particular reference to various contemporary iconographers.

———————————————-

[1] Adapted from a talk given at Kellogg College, Oxford, Feb 27th 2015, The Christian Religious Image, organised by the St John Cassian Association.

[2] Leonid Ouspensky, Theology of the Icon, Vol. 1, SVS Press, 1992

[3] Most recently a published talk by Evan Freeman, Rethinking the Role of Style in Orthodox Iconography:

The Invention of Tradition in the Writings of Florensky, Ouspensky and Kontoglou, in “Church Music and Icons: Windows to Heaven: Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Orthodox Church Music University of Eastern Finland Joensuu, Finland 3–9 June 2013”, published by The International Society for Orthodox Church Music, 2015, p. 350-369.

[4] In English there is Landscape elements in Iconography, Irina Gorbunova-Lomax, Brussels Academy of Icon Painting, Brussels.

[5] See for example her blogs http://ikonographics.blogspot.gr/2016/02/revisiting-patristic-theology-of-icon.html

[6] For example George Kordis, “Μορφή και Εικόνα. Η Προβληματική για την σχέση μορφής και εικόνας κατά τους Εικονομάχους και Εικονοφίλους, Doctoral thesis, University of Athens, 1991..Also, in English translation,

Icon as Communion, Caroline Makropoulos (trans.), Brookline, Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2010.

[7] http://ikonographics.blogspot.co.uk/2016/02/revisiting-patristic-theology-of-icon.html

[8] Acts of the 7th Ecumenical Council. Mansi 13, 340E

[9] Acts of the 7th Ecumenical Council. Mansi 13, 340E-342A

[10] Wilhelm Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, trans. Hilton Kramer (New York: International Universities Press, 1953; originally published in German as Abstraktion und Einfühlung in 1908), 17.

[11] http://ikonographics.blogspot.co.uk/2016/02/revisiting-patristic-theology-of-icon.html.

[12] The Pictorial Metaphysics of the Icon: Part II

by Fr. Silouan Justiniano • January 5, 2016, in “Orthodox Arts Journal” https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/the-pictorial-metaphysics-of-the-icon-part-ii/#_edn11

[13] On the Prescription of Heretics.vii, 45

[14] St. Maximos the Confessor, “Second Century on Theology,” in: The Philokalia: The Complete Text, by St. Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain and St. Makarios of Corinth (ed.), G.E. E. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware (trans.), Vol. II, London, Faber and Faber, 1981, p. 156.

[15] John of Damascus, On the Divine Images, 1.17, translation by D. Anderson from On the Divine Images: Three Apologies against Those who Attack the Divine Images (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1980), p. 25

[16] G. Kordis, Icon as Communion, Caroline Makropoulos (trans.), Brookline, Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2010, p. 2.

Thank you ,Aidan Hart, for this excellent article.

Dear Aidan,

We are glad to see this article touching a very important area of iconography practice.

Now you can use also the English version of ‘Truth and Fable’ which we have put into the public domain via http://mmekourdukova.livejournal.com/467108.html.

Irina + Michael

Thank you, Irina, for translating the book. I have read it in Russian, and it the most significant work in the field; brilliant in fact, pure genius! Everyone should read it, and many will run screaming for cover upon reading it, God willing.

Thank you, Kathleen, Irina and Michael. It is a little offering which I hope will stimulate contributions from others on the subject.

Aidan

Aidan Hart:

I very much appreciate your occasional papers on iconography…including this one and I look forward to the remaining part(s).

I want to share this with others, in print form, as I have with previous papers of yours; however when I tried printing it out on letter-size paper, the pagination registration didn’t work and the images were often cut in two and printed on separate pages, or else were “collapsed” into only partial images. Is it possible for you to have these pages worked to conform to normal US letter-size paper?

I know you to be English so perhaps you wrote this in England where paper standard sizes are different from those in the USA, which is where I am trying to print them. I would very much appreciate your help.

Thank you…and thank you for this article.

Thank you so very much for this wonderful information.

Thank you, Aidan.

Your articles are food for thought. I am publishing the two links in my American Association Of Iconographers Blog. I so much value your scholarship and contribution.

Blessings

Christine

Everyone should read Irina Gorbunova’s book “Truth and Fables.” It is the best inoculation from the fantasies of the iconology.