Similar Posts

The Pictorial Metaphysics of the Icon

Part II

By Fr. Silouan Justiniano

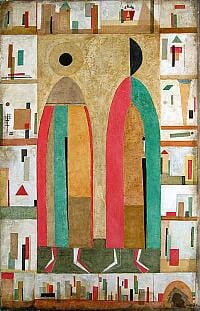

Boris and Gleb, by Andrei Kolkutin, 2005. Oil on canvas.

Suprematism and the icon collide. A postmodern commentary on the coopting of the icon by Modernism.

…a view of the sensible world that relies exclusively on sense perception, are indeed scales, blinding the soul’s visionary faculty and preventing access to the pure Logos of Truth.

St. Maximos the Confessor, Second Century on Theology[i]

But just as linear perspective reached the apex of its acceptance as a convention, suddenly Jesuit missionaries exported it to China as a vehicle of Christian iconography… However, the new perspective contained one insuperable contradiction. The religious images appeared to the Emperor’s eyes solely as technical marvels, and as such were accorded an almost religious respect. The evangelical message was ignored since, for the Chinese, the manner of representation was not realistic.

Massimo Scolari, Oblique Drawing: A History of Anti-Perspective[ii]

The spectacle of unregulated image-making in the West was especially glaring when viewed from the outside. Byzantine clerics, for example, were astonished at the license taken by the Western painters and refused to acknowledge Western images as legitimate.

Alexander Nagel, The Controversy of Renaissance Art[iii]

Style Then and Now

What we are dealing with is ultimately a problem of perception, modes of viewing, whether it has to do with notions of “lifelike” accuracy or style. Indeed, the modernists interpreted icons through their ideological lens of formalist aesthetics and preference for abstraction, in ways that completely overlooked how the Byzantines and Orthodox faithful viewed them within a devotional and liturgical context. They turned the icon into an autonomous art object and the Byzantines to proto modernists. However, the fact that the Byzantines did not speak in formalist terms does not mean that they did not make distinctions between what we refer to as abstract and naturalistic styles. They were indeed aware and extremely sensitive to these kind of stylistic distinctions and made pictorial choices accordingly as a way of conveying definite meanings. As Maguire notes:

When the Byzantines wrote about art, they did not discuss it in the vocabulary of twentieth-century art criticism, making an artificial distinction between style and iconography. They discussed the interrelationships of form and meaning in their own vocabulary, which was largely then vocabulary of Late Antique rhetoric. For this reason, many twentieth-century writers have accused the Byzantines of being blind to what modern critics would call style, especially styles now considered to be abstract and unclassical. But a close reading of the Byzantine writers reveals that they were, in fact, extremely sensitive to styles and to their meanings, whether those styles were in present day terms, classicizing and naturalistic on the one hand, or abstract and schematic on the other.[iv]

He also adds at the end of his study:

In summary, different artistic styles could carry definite messages…The style could be classicizing and naturalistic, as in the case of the Paris Psalter, or it could be highly abstract, as in the case of imperial portraits in Hagia Sophia. But, in either case, style was part and parcel of the message of the work of art. Style did have a political history in Byzantium, and that history is a valid subject of enquiry for the art historian.[v]

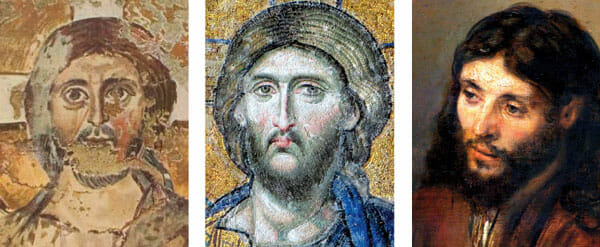

Yet, the Byzantines did not explicitly speak of a stark dichotomy opposing abstraction to naturalism, on the grounds that the former was spiritual while the later carnal, as the pioneers would tend to in their defense of the traditional icon. So in seemingly absolutizing and equating the abstract style with spirituality, making it the locus of the theology of the icon, and turning it into an ideological weapon against post-Renaissance naturalistic painting, places the pioneers in a vulnerable position, liable to being accused of “modernism” and “dualism”. However, as noted earlier, this fact should not lead us to dismiss their intuition about the metaphysical implications evident in abstraction and naturalism as complementary pictorial tendencies. These implications might have been taken for granted, remained implicit and gone undiscussed by the Byzantines in the same terms as the pioneers, nevertheless, they are to be found in their icons, articulated pictorially if not in text. Moreover, it hardly needs pointing out, in order to better understand the pioneers we are to see them, not only in light of what the Byzantines had to say about their icons, but also in light of the undeniable contrast between Byzantine naturalism as compared to that of the Italian Renaissance.

Thus although the Byzantines might have felt comfortable implementing their own version of classical naturalism, nevertheless, after the Renaissance the question of naturalism as such could never be the same. It now had taken a new form unfamiliar to their eyes and become the embodiment of a competing worldview and theology. Styles had come into conflict. For, in fact, although it might come as a surprise, in encountering the breakthroughs of early Renaissance painting the Byzantine viewer remained unconvinced of their accuracy, since the compositions did not follow the pictorial codes of his tradition.[vi] Renaissance illusionism was perceived as disorienting, alien to the ethos of the Orthodox Church. We find an example of this in the account recorded by the Byzantine cleric, Gregory Melissenos, which relates his experience upon viewing the works found in a Latin church at the Council of Ferrara:

When I enter a church of the Latins, I do not revere any of the [images of] saints that are there, because I do not recognize any of them. At the most, I may recognize Christ, but I do not revere Him either, since I do not know how he is inscribed. But I make my own [sign of] the cross and revere it. I revere the cross that I make myself, and not anything else that I see there.[vii]

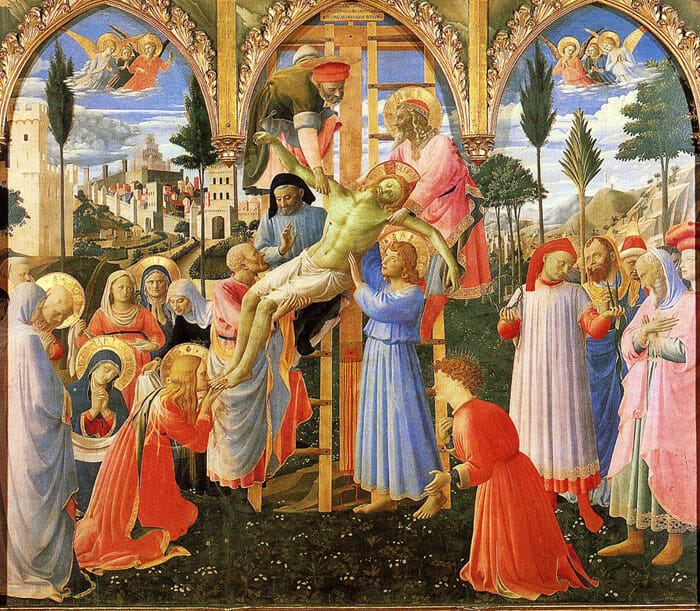

Descent from the Cross, by Fra Angelico, 1432-1434. Tempera on Panel, 69 in. × 73 in. National Museum of St. Marco, Florence.

This Florentine painting was finished around four years prior to the Council of Ferrara-Florence. So it gives us an idea of the kind of developments in perspective Gregory Melissenos could have encountered.

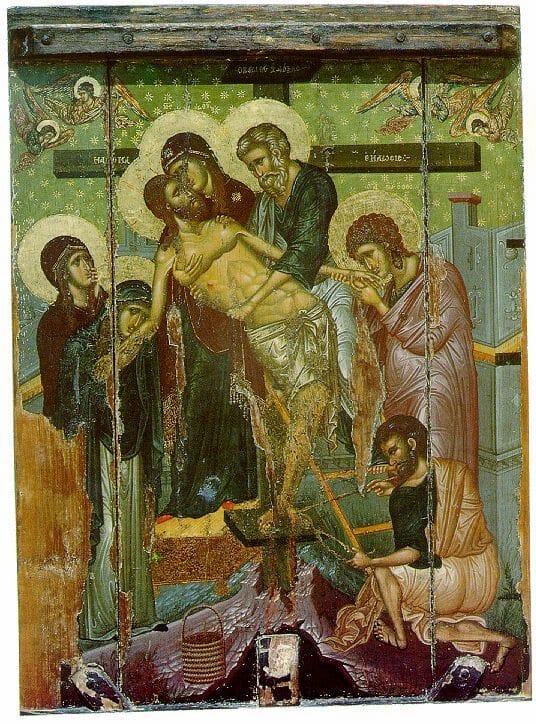

Descent from the Cross, Byzantine, 14th cent. From the Church of Saint Marina in Kalopanagiotis, Cyprus. This is the kind of image Gregory Melissenos would have been more familiar with.

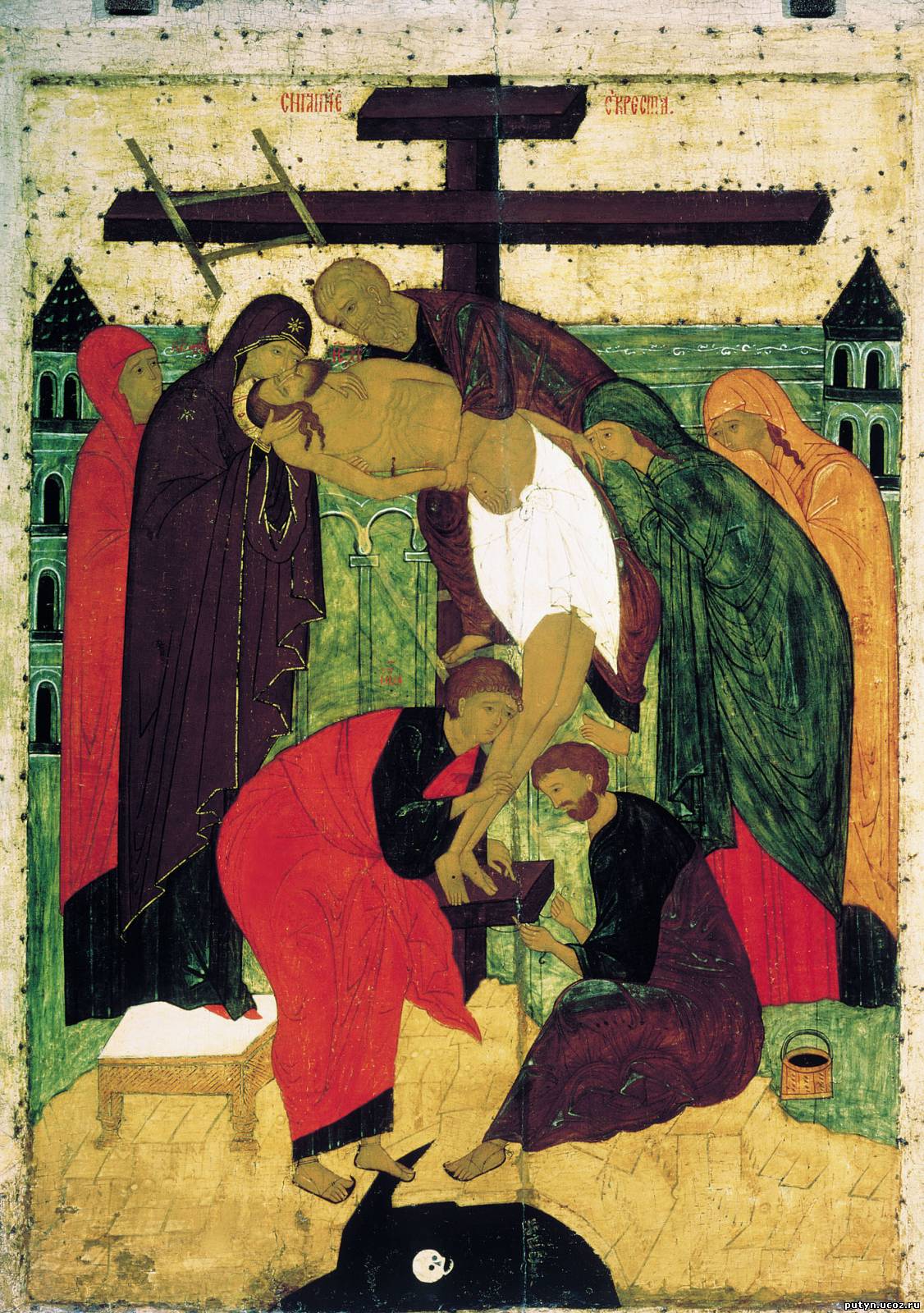

Descent from the Cross, Novgorod School, late 15th cent. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Whereas volume predominates in the icon from Cyprus above, in this work flatness takes the lead. Yet, both icons are indeed more abstract than both the the Florentine and Nethelandish works.

Descent from the Cross, by Rogier van der Weyden, ca. 1435. Oil on Oak panel, 220 x 262 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid. This Early Netherlandish work is more or less contemporaneous with the work shown above by Fra Angelico. Much more forceful in its emotionalism and crisp illusionism, heavier and less atmospheric than the later, but within the same ambit of Early Renaissance naturalism.

It is clear then that pictorial conventions or style embody an ethos, a mentality, an idea, a code that communicates a conception, a paradigm, a worldview. If it wasn’t so then El Greco would have just continued painting his Cretan icons when moving to Italy and then to Spain. But, no, along with becoming Roman Catholic he changed his style of painting, adopting Renaissance illusionism, in order to conform his art to the expectations of his new clientele. It was more than a matter of taste. He needed a new visual language that would be recognizable and accepted as “inscribed” according to the demands of Latin theology. Style is never neutral; it certainly mattered then, and does so now.

Dormition of the Theotokos, by El Greco, 1565- 1566. Tempera and gold on panel, 24.2 in × 18 in. Holy Cathedral of the Dormition of the Virgin, Hermoupolis.

In this work, painted towards the end of El Greco’s Cretan period, we see traces of Venitian Mannerism in the use of space and atmospheric effects, mainly in the depiction of the assumption of the Theotokos in the center of the composition. Nevertheless, in overall effect it predominantly retains adherence to the Byzantine models.

Assumption of the Theotokos, by El Greco, 1577. 157.9 in x 90.2 in. Art Institute of Chicago. This was El Greco’s first commission in Spain.

Ultimately what all of this makes clear is that the notion of pictorial “realism” as such is in fact a relative term. What will appear to one person or culture as “accurate” or “lifelike” can be perceived as a distortion to another and vice versa. Even a photograph, taken for granted by most as a mirror of the phenomenal world, will be disorienting to a tribesman who values his “abstract” pictograms as precise articulations of the world around him. For him the photograph is not an accurate “style”. For him “abstraction”, that is, pictorial symbolism, is truly full of life. In short, what we take for granted as “realistic” is based on an interpretation of reality, a metaphysical assumption. So the question is whether or not our metaphysics conform to the truly Real.

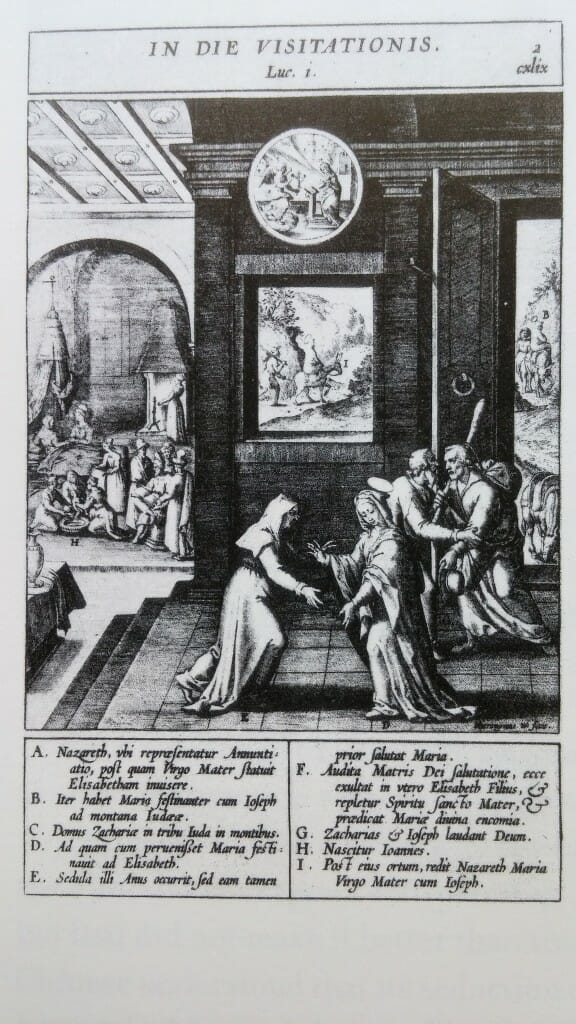

The Visitation of St. Elizabeth. Geronimo Nadal, Adnotationes et meditationes in Evangilia (Antwerp, 1595). In their missionary efforts to convert the Chinese (starting in 1583 to the dissolution of the Society of Jesus in 1773) the Jesuits presented them with perspectival religious images such as this one. But, to their surprise, the Chinese did not find them accurate in their realism.

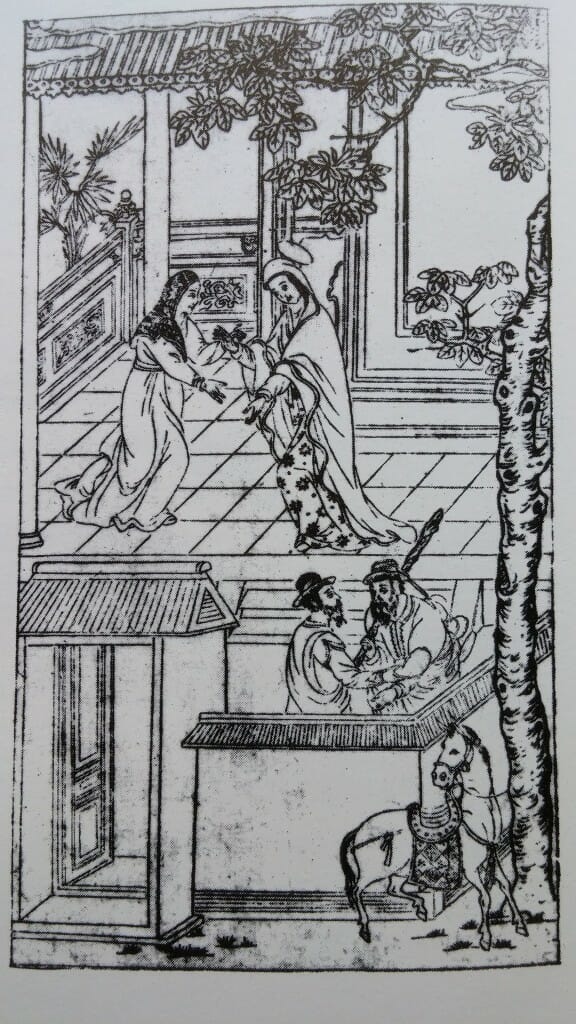

The same scene as above “in Chinese style” in Giovanni da Rocha, Metodo del Rosario, 1620. Ironically the colonizers became colonized. Seeing that perspectival representation was not working the Jesuits reversed their strategy and adopted the Chinese methods of representation. As M. Scolari describes: “For Chinese culture, parallel projection was a sort of symbolic form, profoundly rooted in a pictorial experience that knew almost no interruption until the recent past. Changing the way of seeing, and therefore of representing, meant changing the mode of thinking, which was a futile exercise as long as it was conceived in terms of a conversion from the outside. Additionally, the attempt to institute a single viewpoint contradicted the very roots of Chinese thought, in which man was not the measure of all things. Rather, according to the Taoist conception, it is nature that expresses itself through the artist” (M. Scolari, Oblique Drawing, p. 348. See note ii).

Pictorial Metaphysics

This brings us to the distinctiveness of the traditional or Byzantine style as indeed a suitable means by which to embody Orthodox metaphysics. This is exactly what the pioneers affirmed. This suitability depends on the right use and understanding of the “abstraction” vs. naturalism dichotomy, terms which are not to be seen through a modernist lens. Rather, they are to be interpreted according to the phronema of the Church.

First, it should be clarified that when St. John says that the icon, “must point towards the inner, spiritual essence…,” he is not speaking in favor of the false notion of the possibility of depicting the essence as such, nor is he promoting the idea that the icon itself partakes of the nature of the person depicted. Let us recall that the Fathers writing against the iconoclasts said that icons of Christ depict not the divine nature (essence) as such but the person (hypostasis) of Christ, insofar as, and to whatever degree that, it is possible for “Him” to be depicted. The error made by the iconoclasts was precisely because they argued that the iconodules were trying to depict the divine nature.[viii]

However, on the other hand, St. John does imply that we can indeed give intimations of the divine nature through symbolic depiction of the human likeness of the Logos incarnate, by virtue of the hypostatic union. Likewise, George Kordis notes, “According to the Church’s understanding, the face is the image of a person; it represents that person and reveals his or her being, without of course depicting his essence. Every person – including Christ, for He is the perfect human being – is represented or revealed through the image of his hypostasis” (Our emphasis). As noted earlier, “abstraction” can, and should, facilitate this aim.[ix] In so doing it functions as a method of pictorial “purification” in order to reveal that which is concealed. In Kordis’ words:

The painter removes all elements that are inappropriate and satisfy only human curiosity, but do not serve the sacred mission of the icon. So the icon painter first makes the icon more abstract than a photo. And then, the artist renders this purified form in an artistic manner which is appropriate to the sacred person.[x]

Just as God, in His essence, is beyond all knowledge, although it is possible to know Him through His uncreated energies, so likewise, in the Incarnation, we come to the knowledge of the formless Logos as He is energetically manifested through His hypostatic form and likeness. Hence, in so far as it is possible, the iconographer’s task is to depict these energetic manifestations which are in fact radiances of His divinity and therefore truly linked to Him.[xi] The icon, then, acts as a mirror of these radiances. The same principle applies to the depiction of the spiritual state of the deified saints. As St. John of Shanghai says, finishing his aforementioned passage and clarifying what he means by “essence”, “The task of the Iconographer is, precisely, to render, as far as possible, and to as great an extent as possible, those spiritual qualities whereby the person depicted acquired the Kingdom of Heaven…” (Our emphasis). In short, the virtue of the saint is noetically intuited, as it is manifested in his likeness, and then re-presented through symbolic realism. Hence, the iconographer intuits the likeness of the saint as a true appearance, not as the word sometimes implies, that is, as illusoriness, but, rather, as an unveiling of the fruits of “participation in the divine nature,” which is interpreted as meaning “energetically”, or “kata energeian” (i.e., as theosis).

So although illusionism is not consistently absent in the history of the icon, some kinds of illusionism or naturalism remain questionable as appropriate to its liturgical function. It all depends on what we mean when it comes to “naturalism”. As we have seen these terms are to be dealt with carefully. It is a matter of the degrees of naturalism, which in turn carries a metaphysical implication that can be problematic for icons. For some naturalism implies a kind of empiricism that truncates reality to a purely temporal, materialistic, and corruptible frame of reference.[xii] What the pioneers had in mind is this empiricist, excessive, crass, sensual, and sentimental naturalism clearly seen in the late Gothic, High Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque, Rococo, 19th century Academism, etc.[xiii] These are the kinds of excesses they rightly resisted and opposed as not in conformity with the metaphysics of the icon and therefore stylistically problematic.

The Transfiguration, by Raphael, 1516-20. Tempera on wood, 159 in. × 109 in. Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City.

An exemplary work by one of the masters of the High Renaissance.

The Resurrection, by Agnolo Bronzino, 1549-52. Oil on panel, 445 x 280 cm. Guadagni Chapel, Santissima Annunziata, Florence, Italy. The inappropriate sensuousness of Mannerism

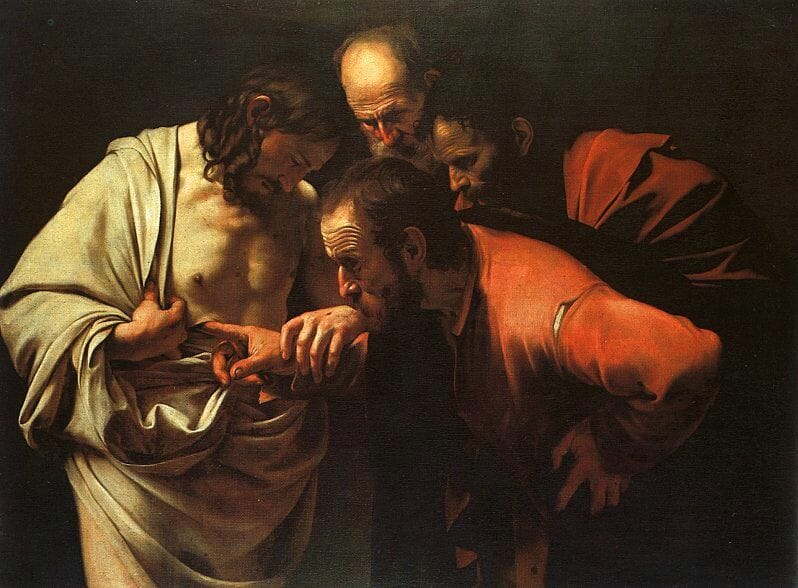

The Incredulity of St. Thomas, by Caravaggio, 1601-1602. Oil on Canvas, 42 in. × 57 in. Sanssouci, Potsdam.

Proto-Baroque’s crass physicality.

The Great Last Judgement, by Peter Paul Rubens, 1614-1617. Oil on canvas. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

Melodramatic Baroque.

Pietà, by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1876. Oil on canvas

90.6 × 58.3 in. A work by one of the foremost Academic painters of the 19th century demonstrating his command of “photographic accuracy”.

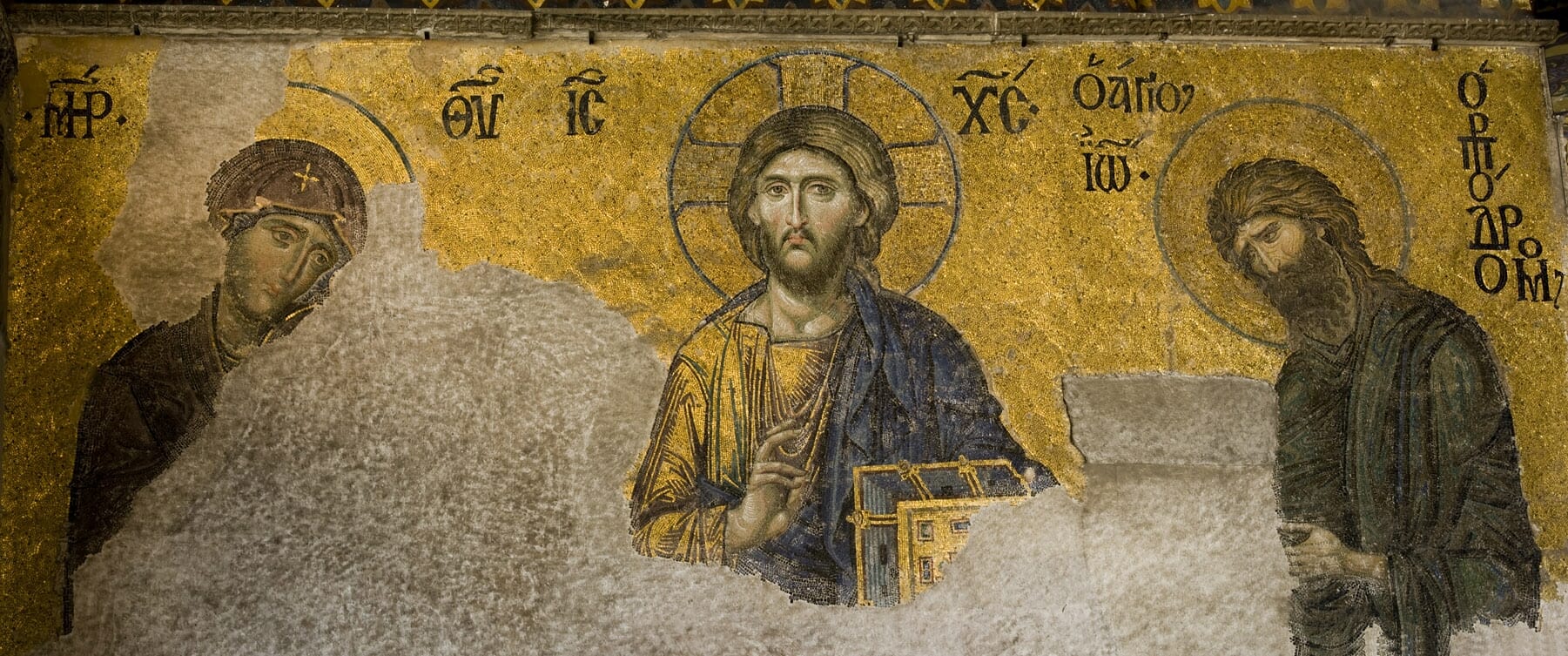

All of this involves the deep black passages and dramatic spotlights of chiaroscuro, sfumato and obvious cast shadows that are for the most part absent features of Byzantine works and most schools of iconography. It is true that shadows are not completely absent, as can be seen in the indisputable Late Byzantine masterpiece, the Hagia Sophia mosaic Deesis, in which we can find a cast shadow on Christ’s neck. But, it couldn’t be otherwise since for the depiction of form and volume the use of a light/dark tonal variation is necessary. So a “shadow” area will always be present. Nevertheless, comparatively speaking, cast shadows as such never became an essential component of Byzantine works as they did in the Renaissance, where they are starkly present.[xv] Hence, we’re dealing with a matter of degrees of emphasis. In short, even if we see cast shadows in the 5th century works of Ravenna, the fact remains that this practice fell out of use and ceased to be a main component of what were to become the crystallized pictorial principles of icon painting.[xvi] This is why Florensky could be so bold as to say that, “in icon painting, shadows have no place. The icon painter never enters into an affair with darkness and so he never creates shadows in the icon.”[xvii] He is in fact intuiting the metaphysical significance of what is commonly dismissed as mere pictorial convention:

Because the icon painter depicts the being of a real thing, even the essential goodness of the being: a shadow, on the other hand, is not being but absence of being. Thus, to depict a shadow would be to characterize an absence by something positive, by a presence ̶ and that would be a radical distortion of ontology.[xviii]

Deesis, Mosaic, 13th cent. Hagia Sophia, Constantinople. This is definitely an important example, since we do actually see in it cast shadows (i.e. on the neck of the Theotokos and the left hand side of the Lord’s neck) caused directional light, elements that run contrary to Ouspensky’s and Florensky’s claims that these are absent in icons. Moreover, the use of directional light contextualizes the mosaic into its immediate environment. This is done by representing the image as if illumined from the right hand side of the Lord, the same side from which light literally floods in through a window and illumines the gallery in which the mosaic is found. Hence this device gives the impression that the the image is continuous with our world. It might then at first appear as if this mosaic is in full conformity with naturalistic paintings from the Renaissance in its use of light, which seek to create a fiction that their light source is outside the painting and continuous with our world. However, in no way can this work be thought of as an instance of “chiaroscuro” in Byzantine art. The background is still gold and flat, lacking any suggestion of illusionism and functions as an additional internal light source. So what we have here is the suggestion of multiple forms of illumination, both physical and divine, external and inner, directional and all-encompassing. Still, due to the large expanse of reflective golden background and the scintillating effect of the tesserae, its illumination can be seen as predominantly internal and self-generated. The mosaic both represents and gives off light. It could be said that Ouspensky’s and Florensky’s sweeping claims concerning light and shadows in icons is mainly based on the use of defused light in Russian icons, such as can be seen in Rublev’s Trinity. Be that as it may, their generalizations, although not completely unfounded, have contributed to the common misconception that there have never been shadows whatsoever in icons. Hence, much confusion has arisen from attempts at the “systematization” of this and other misconceptions. As the Deesis mosaic shows, the key is to aim at an approach that is both/and, rather than either/or in making assessments as to what is and what isn’t traditional in theologically based style icons.

Another detail that should be taken into consideration in this work is the use of figure/field interchange as we saw it used earlier in the mosaic of the Archangel Gabriel in the apse of Hagia Sophia. This photograph is particularly effective in showing how the Lord’s golden chiton visually becomes one with the reflective gold background. His torso is as if continuous with the golden light thus appearing “dematerialized.” The golden Gospel book cover further emphasizes the figure/field ambiguity. This is indeed a very effective way of conveying the Lord as the “Light of the world.” He is represented as both truly physical yet beyond the limitations of physicality. This is neither a Docetic nor a Nestorian Christ. So, once again, the point is that this mosaic both conveys the Lord’s human corporeality and his divinity, through the symbolism of pictorial devices. Here is an instance of an “union without confusion or division” of naturalistic and abstract means.

But even if Florensky exaggerates about shadows, nevertheless, in the end his mystagogical interpretation is not wholly unfounded but, rather, accords with the true function of the icon: the depiction of the inherent ontological goodness of created beings, and those who have attained to their true logos in becoming one with the Logos. The icon, in other words, asserts our ontological grounding in the One who truly is, rather than our “flowing away” from Him into non-being. It asserts being rather than becoming. In “flowing away” we become “shadows” of our true selves, in returning to Him we attain to Reality, that is, our true Self. For as St. Maximos the Confessor says, “He restores me in a marvelous way to myself, or rather to God from whom I received being and towards whom I am directed, long desirous of attaining happiness.”[xix] A happiness that is nothing other than becoming everything that God is, yet without being confused in essence. Speaking of the logos of beings St. Maximos also notes:

According to the creative and sustaining procession of the One to individual beings, which is befitting of divine goodness, the One is many. According to the revertive, inductive, and providential return of the many to the One ̶ as if to an all-powerful point of origin, or to the center of a circle precontaining the beginnings of the radii originating from it ̶ insofar as the One gathers everything together, the many are One. We are, then, and are called “portions of God” because of the logoi of our being that exist eternally in God. Moreover, we are said to have “flowed down from above” because we have failed to move in a manner consistent with the logos according to which we were created and which preexists in God.[xx]

This is the Reality that the traditional icon seeks to remind us of in its symbolic pictorial forms and in depicting the saints, those who have returned to the One by moving in a manner “consistent with the logos” of their being.

Indeed, crass naturalism is problematic since it, ironically, falsifies. It pretends to capture truth while it deceives with fleeting appearances. It in fact lives up to the negative connotation of its other name ̶ illusionism. It relegates reality to fallen nature, untransfigured, and presents this mode of existence as the only true reality.[xxi] Moreover, as noted earlier, the current notions of “realism” as pictorial ideology ignore, if not completely deny, that art is in fact ultimately symbolic and communicative, an interpretation of reality that carries a worldview, and not merely a neutral mirror of the world. It is then not such a surprise to find Erwin Panofsky aptly titling his legendary and influential work, Perspective as Symbolic Form.

The icon, then, on the other hand, is supra-realistic, it is a symbolic realism that speaks the truth by bypassing the tendency to fixate solely on sense perception, the surface or mere phenomena, while not completely abandoning Creation as a manifestation, a theophany of the Uncreated.[xxii] It reveals a mentality and not merely a sensation. It reflects a noetic way of seeing in conformity with the Truth of the Gospel.[xxiii] This Truth of course places the spiritual above the carnal without positing a “dualistic” disdain for the body. Rather, in placing the spirit or noetic above the corporeal,[xxiv] it witnesses, seeks, and leads to the transfiguration of Creation and the body in deification. “The body is sown in corruption, it is raised in incorruption…It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power. It is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body.”[xxv]

Composition With Red, Blue and Grey, by Piet Mondrian, 1924.

Here we see Mondrian’s pursuit of “pure-abstraction.”

All we’ve said so far shows that when it comes to pictorial form, traditional icons generally keep a tension between abstract and naturalistic qualities. This is because reality itself consists of intelligible (noetos) and sensible (aisthetos) realms. These spheres of being are symbolically conveyed by abstraction and naturalism respectively. We can then perhaps say that an attempt at pure-abstraction can imply a disregard, if not utter disdain, for things of sense or matter, while an overemphasis on naturalism is an obsession with corporeality, sensuality, or empiricism.[xxvi] Both extremes are to be shunned as we have said elsewhere. As long as an icon finds itself between these two poles it will not go awry in what can be called its incarnational aesthetics– the “union without confusion or division” of the intelligible and sensible as expressed in pictorial form.[xxvii] The metaphysics from which this aesthetic arises is expressed by Gregory the Theologian in his Orations, as he praises Man as microcosm and crown of creation, in whom we find the sensible and intelligible intermingled:

Mind and Sense remained distinct with their boundaries, bearing within themselves the Magnificence of the Creator Logos, but praising silently…Nor was there any mingling between them; nor yet were the riches of God’s goodness manifested…till Man was placed on earth as a kind of second world, a microcosm, a new angel, a mingled worshiper… visible and yet intelligible,…to be the husbandman of immortal plants.[xxviii]

Similarly, the icon is a liturgical expression of “mingled worship”, the harmonious coming together of the intelligible and sensible in praise of God. Therefore, returning to St. Maximos, in the icon “abstraction”, as an act of “drawing out”, rather than being an “escape” from Nature, is in fact truly “realistic” for it is a peering into and unveiling of the mystery of the inherent goodness of beings, their grounding in divinity and transfiguration ̶ that is, the attainment of their true incorrupt Nature. Through “stripping the surface” of sensible things it draws us closer to the apprehension of inner principles (logoi). Naturalism, on the other hand, as was said earlier, is in fact illusory since it takes Nature in its fallen mode of existence and sensory perception as the sole measures of reality and knowledge. Hence, pictorial abstraction, as an act of “drawing out” the intelligible foundation from the sensible, as a pictorial reflection of noetic intuition, parallels what St. Maximos calls the act of “omnipotent reason”, as it divides the sea of the deception of sensible things, as Moses divided the Red Sea with the rod:

Thus the great Moses broke apart the deception of sensible things, or, to speak more precisely, he stripping away the surface ̶ just like the sea ̶ with a blow of omnipotent reason (symbolized perhaps by the rod), and provided the people, who were hastening toward the divine promises, with a firm and unshakable ground beneath their feet, by which I mean the foundation of nature that is concealed below the level of superficial sensation. This foundation is visible to and may be clearly defined by right reason…[xxix]

This is the context in which “abstraction” as a pictorial tool of the icon is to be seen. It is the means by which ontological gold is extracted from the raw ore of “deceptive sensation.” That is why Ouspensky says that in the icon, “Colors do not imitate the colors of the object,” [xxx] for the aim is not the duplication of a sensual apprehension but, rather, the articulation of a pictorial idea in conformity with the spiritual meaning, the logos, of the subject at hand. Thus the carnal eye is not the sole means by which to capture a “lifelike” image full of pneuma. In other words, the iconographer is not confined to the surfaces of some model propped up in front of him, as an Academic painter of the 19th century like William-Adolphe Bouguereau would be, in an attempt to mimic with “photographic” accuracy just the right tones, the sfumato and nuances of hue, in the drapery and sensuous bodies he wants to depict. Rather, he is actually symbolically re-presenting what he has apprehended noetically, with eye of the heart.[xxxi] Without stopping at the surface he reaches for the foundation. The aim is not illusionism, neither an escape from Nature, but the unveiling of Reality.

Saints Boris and Gleb with Scenes from Their Lives, 14th cent. 134 x 89 cm. From the Church of SS Boris and Gleb in Kolomna.

To be continued…

NOTES:

[i] St. Maximos the Confessor, “Second Century on Theology,” in: The Philokalia: The Complete Text, St. Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain and St. Makarios of Corinth (ed.), G.E. E. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware (trans.), Vol. II, London, Farber and Farber, 1981, p. 156.

[ii] M. Scolari, “The Jesuit Perspective in China,” in: Oblique Drawing: A History of Anti-Perspective, Massachusetts, The MIT Press, 2012, pp. 341-342.

[iii] A. Nagel, The Controversy of Renaissance Art, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2011, p. 21.

[iv] H. Maguire, “Style and Ideology in Byzantine Imperial Art” in: Gesta, Vol. 28, No. 2, 1989, p. 217.

[vii] H. Maguire, op. cit., 1989, p. 46.

[viii] As Archimandrite Vasileios notes: “In the icon of Christ we confront neither the invisible and unimaginable divinity (who can circumscribe the uncircumscribable?) nor simply the humanity alone how can one separate out the humanity in Him who in His Person indivisibly and unconfusedly united the divine and human nature?). In the icon is shown forth – is imaged – the single hypostasis of the incarnate Logos of God. And in venerating the icon we venerate the Theanthropos, the divinity and the humanity, the flesh of the Lord that has become one with God. ‘It is not the nature, but the hypostasis of the person portrayed that is shown forth in the icon’ (St. Theodore Studite, P. G. 99, 405A). For this reason there are not two acts of veneration, but one, offered to the hypostatic unity: ‘A single act of veneration, not distinguished according to the distinction of the essence but on the contrary identified according to the unity of the single hypostasis’ (St. Theodore Studite, P. G. 99, 497B-C).” Archimandrite Vasileios Abbot of the Holy Monastery of Stravonikita, Mt. Athos, “Theology of Byzantine Icons”, http://users.uoa.gr/~nektar/orthodoxy/tributes/basileios_gontikakhs/theology_of_byzantine_icons.htm, 2009 (accessed 25 November, 2015).

[ix] “In the artistic exposition and rendering of the original, changes may be made (in reality they purify the person depicted, relating them to the viewer), but the alterations cannot be so extensive and so numerous as to destroy the likeness.” G. Kordis, Icon as Communion, Caroline Makropoulos (trans.), Brookline, Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2010, p.47.

[x] Fr. S. Justiniano, “The Art of the Icon in a Post Modern World: Interview with George Kordis”, in: Orthodox Arts Journal, 25 June, 2014, https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/the-art-of-icon-painting-in-a-postmodern-world-interview-with-george-kordis/, (accessed 16 December 2015); Kordis also notes, “In depicting people and natural phenomena and giving them artistic representation, the artist cannot efface the required likeness to the model, or prototype. (According to St. Nicephorus, it is the person depicted or his human form that is the icon par excellence.) In the artistic exposition and rendering of the original, changes may be made (in reality they purify the person depicted, relating them to the viewer), but the alterations cannot be so extensive and so numerous as to destroy the likeness.” G. Kordis, op. cit., p. 48.

[xi] Just as we employ in Scripture word-images for the same, saying word-images like “cloud” and “light” and “whiter than any fuller can whiten” and “glory” and “fire”, and so forth.

[xii] “To the extent that spiritual consciousness grows less and emphasis of faith is directed to the historical character of the miraculous occurrence rather than to its spiritual quality, the religious mentality turns away from the eternal “archetypes” and attaches itself to historical contingencies, which thereafter are conceived in a “naturalistic” manner, that is to say, in the manner that is most accessible to a collective sentimentality.” T. Burkhardt, “The Foundations of Christian Art,” in: Sacred Art in East and West: Principles and Methods, Middlesex, Perennial Books Ltd., 1967, p. 67.

[xiii] T. Burckhardt, “The Decadence and Renewal of Christian Art,” in: Sacred Art in East and West: Principles and Methods, Middlesex, Perennial Books Ltd., 1967, pp. 143- 160.

[xiv] This is definitely an important example, since we do actually see in it shadows caused by directional light, elements that run contrary to Ouspensky’s and Florensky’s claims that these are absent in icons. However, in no way can this work be thought of as an instance of “chiaroscuro” in Byzantine art. The background is still gold and flat, lacking any suggestion of illusionism and functions as an additional internal light source. So what we have here is the suggestion of multiple forms of illumination, both physical and divine, directional and all-encompassing. Still, due to the large expanse of reflective golden background and the scintillating effect of the tesserae, its illumination can be seen as predominantly internal and self-generated. The mosaic both represents and gives off light. It could be said that Ouspensky’s and Florensky’s sweeping claims concerning light and shadows in icons is mainly based on the use of defused light in Russian icons, such as can be seen in Rublev’s Trinity. Be that as it may, their generalizations, although not completely unfounded, have contributed to the common misconception that there have never been shadows whatsoever in icons. Hence, much confusion has arisen from attempts at the “systematization” of this and other misconceptions. As the Deesis mosaic shows, the key is to aim at an approach that is both/and, rather than either/or in making assessments as to what is and what isn’t traditional in theologically based style icons.

[xv] All of this clearly betrays conflicting attitudes towards the symbolic use of light.

[xvi] For a study on the use of gold as light in Byzantine icons see: R. Nelson, “The Gold of Icons”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I9Pgp_pZags, 2013 (accessed 24 December 2015).

[xvii] P. Florensky, Iconostasis, Crestwood, SVS Press, 1996, p. 144.

[xix] St. Maximos the Confessor, Maximus Confessor: Selected Writings, Volume 45 of Classics of Western Spirituality, George Charles Berthold (ed.), New York, Paulist Press, 1985, p. 192.

[xx] St. Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua, Vol. I, N. Constas (ed. and trans.), Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2014, pp. 101-103.

[xxi] By now it should be clear that we are not in any way denigrating Nature as such, since after all it is inherently good and its beauty is clearly a reflection of its ontological grounding in the Uncreated, worthy of being depicted well in all its glory. Neither are we denigrating the value of good non-liturgical art per se. There is no question that in some cases non-liturgical works, such as is clearly evident in Persian or Indian miniatures and Kakemonos, are intensely imbued with a kind of otherworldliness, transmit a sense of the paradisiacal and encourage contemplativeness. The key here is that the kind of naturalism we are discussing tends to, or completely undermines, the possibility of Nature as transfigured. It might depict Nature as good, but not as very good, it represents a bush, but not a burning bush, illumined and enflamed with the fire of divinity. In short, it fails to indicate the radiance of the indwelling logos of beings, to depict nature in all its translucency and sacredness.

[xxii] Sense perception is not completely striped of its sacramental dimension if we perceive in thanksgiving and purification, that is, if we do not consider it as an end in itself. The senses then are organs through which we spiritually perceive. Keeping in mind St. Gregory Palamas, sense perception is not to be replaced with another “spiritual” means of perception, but rather made a means of spiritual perception. The disciples did see the uncreated light on Tabor with their bodily eyes, but grace bearing bodily eye; the eye of their heart and the eyes of their bodies became one in an union without confusion, as sort of mini incarnation.

[xxiii] As mentioned earlier, the Portrait of the Four Tetrarchs porphyry sculpture marked a shift in mentality from late antiquity to the mediaeval period. This shift was to play a role and embraced as congenial in the formulation of Byzantine sacred art. Hence, the icon can be seen as resulting from the confluence of this cultural shift that came prior to the Christianization of the Roman Empire, and the new Christian mentality, that is, a noetic way of seeing according to the Gospel, through which the former pagan pictorial forms were “baptized” and incorporated into the liturgical art of the Church.

[xxiv] This point should be understood according to St. Dionysius the Areopagite’s teaching on the hierarchy of being. It is not so much a vertical hierarchy in which a higher order stands above and apart, disconnected from the lower, rather, the higher order in its plenitude contains the lower, being “larger” than the lesser level that it contains. However, the lower level contains within itself a still lower and “smaller” level. This principle unfolds in consecutive order, each level containing within itself the level immediately below it. Hence, what actually unfolds is a “mediated immediacy” along the consecutive gradations leading from Higher to lower or Center to periphery.

[xxvi]As A. Hart has noted, “In fact pure-abstraction cannot exist, any more than hypostasis can exist without its nature. To abstract means to draw out the essence of something, and yet that essence does not exist apart from the nature that it “essentialises”, directs and animates.” From our private correspondence, 29 November, 2015.

[xxvii] “There is…no true Christian art without a certain degree of “abstraction”, if indeed it be possible to use so equivocal a term to designate that which really constitutes the “concrete” character, the “spiritual realism”, of sacred art. In brief: if Christian art were entirely abstract it could not bear witness to the Incarnation of the Word; if it were naturalistic, it would belie the Divine nature of that Incarnation.” T. Burckhardt, “The Decadence and The Renewal of Christian Art”, in: Sacred Art in East and West: Principles and Methods, Middlesex, Perennial Books Ltd., 1967, p. 150.

[xxviii] St. Gregory Nazianzen, Orations, 45, section 7.

[xxix] St. Maximos the Confessor, 2014, op. cit., p. 171.

[xxx] Our translation from the French from Chantal Savinkoff, “Une leçon d’iconographie avec Léonide Ouspensky: Extraits d’un entreitien avec Chantal Savinkoff,” Paris, February 1974, in: The Orthodox Messenger, Special Issue, “Life of the icon in the West,” No 92, 1983. http://www.pagesorthodoxes.net/eikona/iconographie-ouspensky.htm, (accessed 1 November 2013).

[xxxi] “The icon’s milieu is the ascetic teaching of the Orthodox Church. According to this tradition the highest faculty of the human person is what is best described as the eye of the heart – the nous in Greek, and intellectus in Latin. By the nous we can know things in an unmediated way. If the nous is purified, then it can communicate to the imagination images from the archetypal world, that is, from God. By contrast, an unpurified nous and imagination will throw up arbitrary images, and at worst hellish, irrational images. An art based on such images will oppress the culture into which it is born.” A. Hart, Beauty, Spirit, Matter: Icons in the Modern World, Herefordshire, Gracewing, 2014, p.186.

I am Roman Catholic who came to love, perhaps not understand, Icons in 1950. With what available to me since then, I have tried to educate myself in the philosophy, theology and the writing of Icons. This is the first in-depth study that seems to bring it altogether for me. I see many hours of study and reflection ahead for me on this superb article.

Thank you, Fr. Silouan, for this fascinating and monumental study. You reveal a nuanced middle way of addressing the problem of style in icons. There have been some who claim that Byzantine style is what makes an image an icon. But there are others who claim that style is completely separate from the meaning and subject of icons – that style is only important as a matter of liturgical decorum.

But you show clearly that style, though secondary to the overt meaning of an icon, is not without symbolic meaning of its own, and that it is a key component to the spiritually realistic depiction of saints.

This essay should be required reading for any student of Orthodoxy or iconography!

[…] night, my friend sent me a link to the article ‘The Pictorial Metaphysics of the Icon’ (Don’t let the title scare you). While the article is more specifically talking about icons, […]