Similar Posts

The Pictorial Metaphysics of the Icon

Abstraction vs. Naturalism Reconsidered

Part I

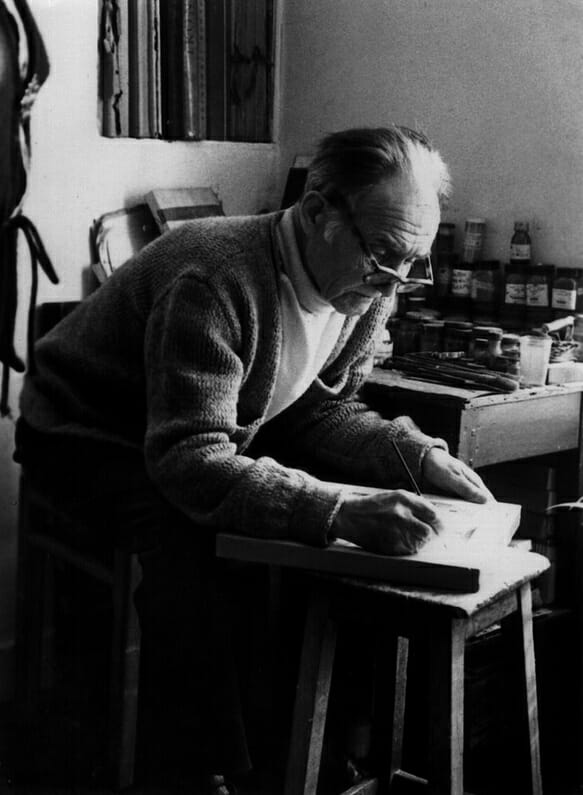

By Fr. Silouan Justiniano

St. Demetrios with Donors, mosaics from the church of St. Demetrios, Thessaloniki, 7th or early 8th cent. Abstraction full of “lifelike” presence.

The Icon is not simply a representation, a portrait. In later times only has the bodily been represented, but an Icon is still supposed to remind people of the spiritual aspect of the person depicted…Thus, we see that an Icon must indeed depict that which we see with our eyes, preserving the characteristics of the body’s form, for in this world the soul acts through the body; yet at the same time it must point towards the inner, spiritual essence. The task of the iconographer is precisely to render, as far as possible and to as great an extent as possible, those spiritual qualities whereby the person depicted acquired the Kingdom of Heaven…[i]

St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco, Discourse in Iconography.

The doctrinal foundation of the icon determines not only its general orientation, its subject and its iconography, but also its formal language its style. [ii]

Titus Burckhardt, The Foundations of Christian Art.

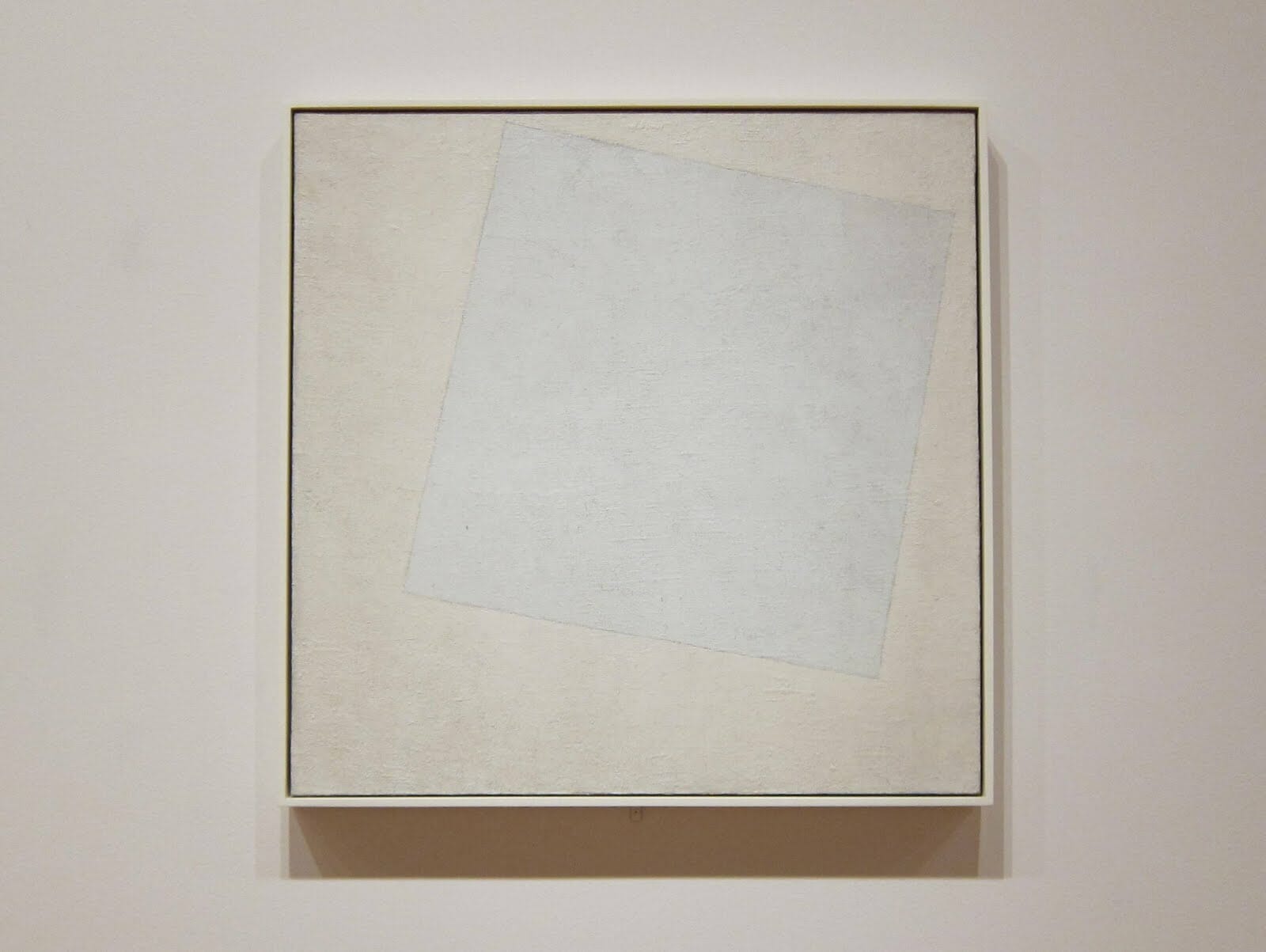

Ironically, along with the advent of Modernism in the 20th century came a new positive attitude towards Byzantine art and all things medieval, in particular the icon. What had been deprecated since the Renaissance as unsophisticated and unskilled products of the Dark Ages were now valued and praised as the most exquisite and masterful examples of “abstraction”. Hence, the icon would be co-opted by the avant-garde for its own ideological purposes, extracted from its liturgical context and function. It became a prime example and justification of an aesthetic striving opposed to what was perceived to be stifling, superficial and used up academic naturalism. Among many modernists abstraction then became equated with the “spiritual” in art, a refreshing oasis in the midst of bleak scientism and materialism, promising creative liberty, inner sustenance without religion, and social revitalization. Abstraction for some became an escape from the tyranny of Nature, a “pure art”, the “icon” of utopianism.[iii]

All of this, however, has nothing to do with “abstraction” as implemented in the traditional icon. Within its Orthodox context it bears quite a different set of metaphysical implications. Indeed, the modernist reappraisal of medieval art has come as a “mixed blessing.” On the one hand, it obscures the true meaning of the icon, yet, on the other hand, it has contributed to its revival and the clarification of its theological significance. The fact remains that to our eyes, whether we have bought into a modernist formalist aesthetic or not, icons do indeed appear more “abstract” than post-Renaissance naturalistic paintings. Moreover, there is no denying that the Church by now has accepted the abstracting tendencies of the “traditional” or “Byzantine style” of iconography as spiritually more efficacious than naturalism. Thus it could be said that “abstraction” has been legitimized as a crucial pictorial component in the realization of the icon’s liturgical function. However, let us not forget, there is also naturalism in the icon. The icon embraces both abstraction and naturalism. But, what kind of naturalism and abstraction are we talking about? The challenge is how to understand these terms in an Orthodox manner, according to Tradition, within the Church’s metaphysical presuppositions, and not through the lens of Modernism.

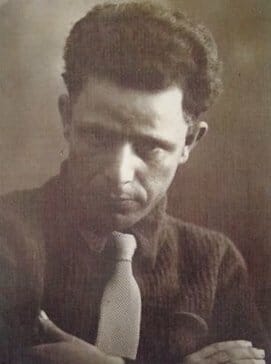

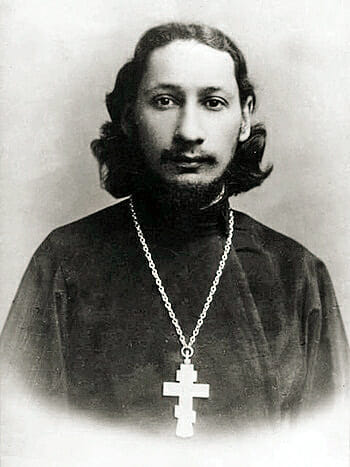

This is definitely part of what the pioneers of the traditional icon revival, Leonid Ouspensky, Photis Kontoglou and Fr. Pavel Florensky, attempted to do in their works.[iv] But, unfortunately, in using the aesthetic vocabulary of their time some have misread them as “modernists”, innovators “aestheticizing” the icon at the expense of iconographic content, its devotional and liturgical function. However, was not their entire project based on the conviction that content and form are inseparable, both of which are inextricably connected to, and arise from, the liturgical and theological underpinnings of the icon? Why else would they attempt to articulate a “theology of the icon”?

Be that as it may, there is no doubt that they were not flawless in every point, in particular when it comes to their rhetorical and polemical manner of defending the Byzantine style of iconography. At times they exaggerate, and consequently some “myths” have gained currency, such as the belief that there are no shadows in icons, that they do not show saints in profile, and that icons are built around an “inverse perspective”. All these examples are intuitions that have something of truth in them, but, when pronounced as overarching “systems”, they are easily contradicted by concrete historical examples. The pioneer’s tendency of speaking over the icon when making their case has led to some of these distortions, woolly tropes, and mystifications which we often encounter today. Indeed, this has led to many pseudo-theological opinions being used today to argue that one particular style, technique or method, within the umbrella of traditional iconography, is spiritually superior to another.

Given all this confusion, it could be said that the pioneers have indeed gone wrong in speaking of a dichotomy between abstraction, or non-naturalism (spiritual) as opposed to naturalism (carnal), since these stylistic categories were never used by the Byzantines in speaking of icons, and ultimately lead to a kind of dubious theological dualism. It is true, as Cyril Mango has noted, that the Byzantines didn’t speak of their icons as “abstract”; they in fact spoke of them as “lifelike”.[v] Those who oppose the exaggerations of the pioneers tend to emphasize this fact, asserting that the icon only “shows” the external form of a saint. Hence, they argue that to claim that the style of the icon helps to symbolically convey the spiritual state of the saint, their deified transfigured human nature, is theologically untenable to say the least. However, we should bear in mind that when the Byzantines spoke of icons as “lifelike” they had not yet confronted the unique peculiarities of the illusionism of the Italian Renaissance. In other words, they didn’t have the advantage of hindsight as we do today to make distinctions between a Byzantine and Renaissance pictorial style. As we will see, within their cultural milieu pictorial realism functioned under a very specific set of presuppositions, expectations and conventions, which would come into question and be perceived in its stark peculiarity, only when their medieval worldview began to come into conflict with the humanism of the Renaissance. It is clear that within this conflict of worldviews the notion of “lifelike” takes on quite a different significance. This also makes evident that an overarching pictorial convention, a formal language or style, accepted and taken for granted by a given religio-culturural sphere, is nothing other than the reflection of its state of consciousness, an interpretation of reality, a metaphysical statement. This is exactly what the pioneers attempted to point out when focusing on the stylistic distinctiveness of the icon, in particular its non-naturalism or “abstraction”, as compared to the problematic naturalism they combated as the infiltration within the Church of a secularizing and humanistic tendency.[vi]

Karp Zolotarev, Theotokos and the Child, late 17th cent. Andrei Rublev Museum, Moscow. In Zolotarev, emplyoed by the Kremlin Armory, we can already see the turning away from the traditional icon and and an attempt in emulating the sensibilities of Baroque naturalism.

In what follows we will attempt to clarify what is meant by the “abstraction” (non-naturalism) and naturalism dichotomy in the theology of the icon. This will serve as a way of addressing some of the misconceptions surrounding the pioneer’s interpretations of the Byzantine or traditional style of iconography. In order to do so the question of “lifelike” in the Byzantine context will be explored. This will help us see how this dichotomy, although present in Modernism, bears a different connotation from an Orthodox perspective, namely, “abstraction” within the ecclesial context of the icon has nothing to do with an “escape” from matter or Nature; it is not to be confused with a form of dualism or pictorial Docetism. On the other hand, although naturalism as such is not to be disparaged outright as “heretical”, nevertheless, some versions do present problems, and if misused within a liturgical context can run counter to the theology of the icon.[vii] This will in turn help to define what kind of “realism” we do find in the icon. In short, what we will elucidate is how the icon’s traditional style has a metaphysical significance not to be taken lightly or undermined, and that the pioneers were not innovators in emphatically upholding its principles but, rather, in undeniable conformity with Tradition.

“Lifelike”, According to Whom?

In an attempt to discredit the pioneers’ emphasis on the icon’s non-naturalism as fundamental to its theology, some have brought as evidence in their favor the fact that the Byzantines themselves considered their works as “lifelike” in accuracy.[viii] Hence, it is claimed, that they did not make stylistic distinctions between abstraction and naturalism as it has become customary among art historians and critics since the 20th century. As mentioned earlier, this has led to the insistence among some iconographers that icons are first and foremost “realistic” rather than symbolic in import. Let us then look at how the abstraction/naturalism polarities have played an implicit role in Byzantine art. This will help us see that, when the icon is described as non-naturalistic, this does not necessarily mean that it is not “lifelike” or “realistic”.

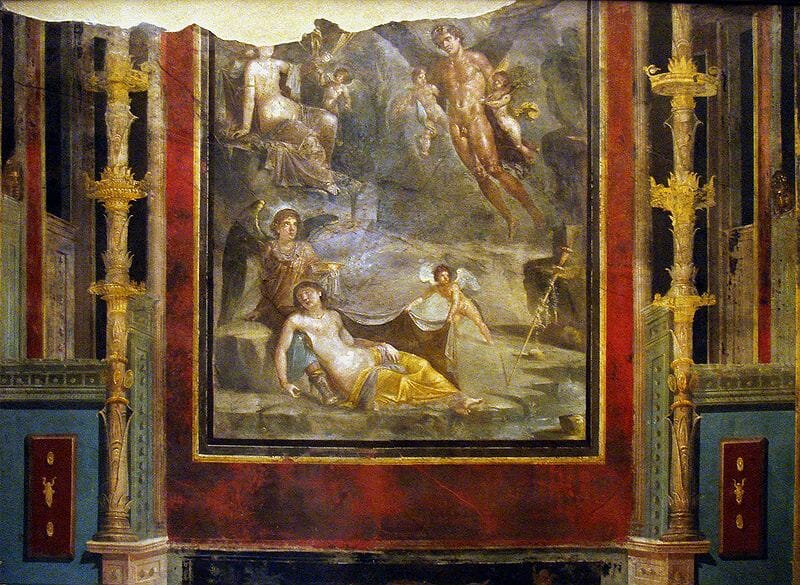

The Wedding of Zephyrus and Chloris 54–68 AD. Pompeian Fourth Style within painted architectural panels from the Casa del Naviglio.

Although it is very true that the Byzantines saw themselves as on a continuum with their Hellenic past, which included the importance they placed on mimesis or a “lifelike” image it is, nevertheless, generally acknowledged that their images also betray a break from the illusionism of antiquity (i.e. Pompeii’s Villa of Mysteries, The Wedding of Zephyrus and Chloris, from the Casa del Naviglio, Pompeii). This break or shift in orientation came into play even before Byzantium in late antiquity, as can be seen in the porphyry sculpture of the Tetrarchs in Venice (formerly in Constantinople), which clearly exemplifies and marks the change in approach to representation from a classical to a medieval mentality. In comparing stylistically the sculpture of the Tetrarchs to the Arch of Constantine in Rome, Ernst Kitzinger says, “stubby proportions, angular movements, an ordering of parts through symmetry and repetition and a rendering of features and drapery folds through incisions rather than modelling”.[ix] He also adds, “The hallmark of the style wherever it appears consists of an emphatic hardness, heaviness and angularity — in short, an almost complete rejection of the classical tradition”.[x]

Left: Demosthenes, Cast from the original in the Vatican. Plaster, 202.5 x 90.3 x 53 cm.

Purchase, 1858, Boston Athenaeum; Right: Sophocles, Cast c.1845 from the original in the Vatican. Roman copy of a statue ca. 330 B.C. Rome. Plaster, 207.5 x 81.5 x 63.6 cm. Gift of George C. Ward, 1858, Boston Athenaeum.

The Tetrarchs, porphyry sculpture, ca. 300 AD. Sacked from the Byzantine Philadelphion palace in 1204, Treasury of St. Marks, Venice.

In other words, what Kitzinger is describing are some aspects of what is generally referred to as the “abstract” tendencies in late antiquity which will continue and become a main component of the stylistic features of the sacred art in the medieval period. Opinions vary as to how to interpret this shift in orientation, but the fact remains that there is a clear turn in methods of representation, from the pursuit of precise verisimilitude, the mimicking of outward phenomena, to a more inward, schematic, direct and symbolic approach. The later tendency will become a congenial component for the pictorial expression of a Christian metaphysic.

Mosaic of St. Sergios,Church of Hagios Demetrios, Thessaloniki, Greece. The hieraticism and abstraction of this work brings it to a timeless and contemplative level. It is clear that the image is meant to lead the viewer to prayerful communion with the saint. Compare the abstraction seen here to the classicism of the illumination below.

David Composing the Psalms, Paris Psalter, c. 900 C.E. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. The manuscript contains 449 folios and 14 full-page miniatures. This illumination is an example of the kind of of work produced during the Macedonian Renaissance of the 10th cent. During this period there was a revival of the ancient Greek culture concerning literature, arts and education.

In painting, particularly, we can distinguish the revival of a Hellenistic or Classical style.

However, the classical heritage was never forgotten and continued to assert influence. This is made evident by the so called “renaissances” (i.e. Macedonian, Paleologan) that would occur from time to time as iconographers revisited and sought to emulate the gracefulness of classical models.[xi] Thus it could be said that the system of pictorial principles of what we refer to as the “traditional” or “Byzantine style” of icon painting arise from a synthesis between late antiquity abstraction and classical naturalism.[xii] As George Kordis puts it:

Byzantine iconographers…instead of devising their own solutions, they turned to the great inheritance of classical and Hellenistic art as well as to that of late antiquity. It was the art of these periods that provided them with the answers they needed. Taking away depth, and using line and local color to construct a form in sculpture or painting, was a technique already prevalent in the second century AD…It was from this important period, the expressionism of late antiquity, that they borrowed the vertical system of perspective, linearism, and of course compositional method. However, Byzantine iconographers also sought to express movement and rhythm in their art. For this they looked at the classical naturalistic tradition, from which they borrowed…plasticity, the dynamic manner of drawing figures on the surface, and the philosophy of rhythm. They took their fundamental artistic principles from these two main sources and used them to construct their own artistic system.[xiii]

Christ Enthroned, Manuel Panselinos, 13th cent. Protaton Church at Karyes, Mt. Athos.

Here we have a style that leans more towards naturalism. It is a masterful example of how classical Hellenic art has influenced the development of the icon. It also demonstrates how abstract qualitie, such as hieratic frontality and flatness (notice the lack of pronounced volume of the blue himation), help to keep the naturalism in check.

Within this system throughout history different schools of icon painting stylistically tend toward one of these the complementary poles, either of abstraction or naturalism, depending on the artistic temperament of individuals or nation, and the nuances of the specific theological message being expressed. Even so, considered as a whole and contrasted to works from the Italian Renaissance, there is no doubt that Byzantine iconography in its symbolic approach generally leans more towards abstraction.[xiv] So how are we to understand its use in the icon?

Christ Enthroned as High Priest, Russia, Kostroma region, Mid 17th cent. 98 x 85 cm. Collection: Jan Morsink Ikonen, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. A good example of a style that leans more towards abstraction.

In describing some of the principles of sacred art Aidan Hart notes the tendency towards abstraction: “Sacred art is always abstract, in that word’s literal sense, in that it ‘draws out’ the essence of the subject. It uses stylistic abstraction to suggest these invisible realities. Such art is therefore not naturalistic, but is realistic, for it affirms the spiritual as well as the corporeal nature of reality. Sacred art typically reveals the union of the inner with the outer, the invisible with the visible. It reveals eternity active within the present, and is therefore closer to reality than naturalistic art, which reflects only the outer phenomena.”[xv] A. Hart’s observations are clearly applicable to the icon and also paralleled by St. John of Shanghai, who tells us that the icon is to convey the “spiritual aspect of the person depicted…Thus, we see that an Icon must indeed depict that which we see with our eyes, preserving the characteristics of the body’s form, for in this world the soul acts through the body; yet at the same time it must point towards the inner, spiritual essence…”[xvi]

Thus, what we find as encapsulating the distinctive features of the icon’s “traditional style” is an interplay, at times a tension, between “preserving the characteristics of the body” (naturalism), and pointing “towards the inner, spiritual essence” (abstraction). However, there is a nuanced distinction that needs to be made. As we have noticed Kordis speaks of naturalism, while A. Hart of “realism.” This might at first just appear to be the same difference. Nevertheless, we should bear in mind that in speaking of “naturalism” in this context we are not to confuse this category anachronistically with “illusionistic” accuracy, as we would expect it today, after the naturalistic paintings of the Renaissance, as a prerequisite for a “lifelike” image. Therefore, as Aidan Hart suggests, in order to avoid this tendency, it would be best to understand “naturalism” in the icon as “realism”, that is, the affirmation of “the corporeal nature of reality.”[xvii] But as we will see shortly, the category of “realism” in the icon also bears a far more profound meaning.

Dormition of the Virgin, by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Oil on canvas, 1604-1606. 145 in. × in.

Louvre, Paris, France. The proto-Baroque illusionist naturalism of Caravaggio.

Dormition of Theotokos, Fresco, 1294–1295. Peribleptos (St. Clement), Ohrid.

Although we do find “naturalism” in the icon it should not be mistaken for the kind of illlusionism found in post-Reconnaissance painting. As Aidan Hart suggests, it is better to think of the naturalism of the icon as “realism”.

In this Dormition fresco find the iconographic “realism” we are referring to, as compared to the “illusionism” clearly seen in the paintings above and below. We can also see how this fresco for all its realism is “abstract” as compared to the Baroque works.

Assumption of the Virgin, by

Peter Paul Rubens,1626.

Oil on panel

190 in × 128 in.

Cathedral of Our Lady, Antwerp.

A classic example of Baroque illusionism.

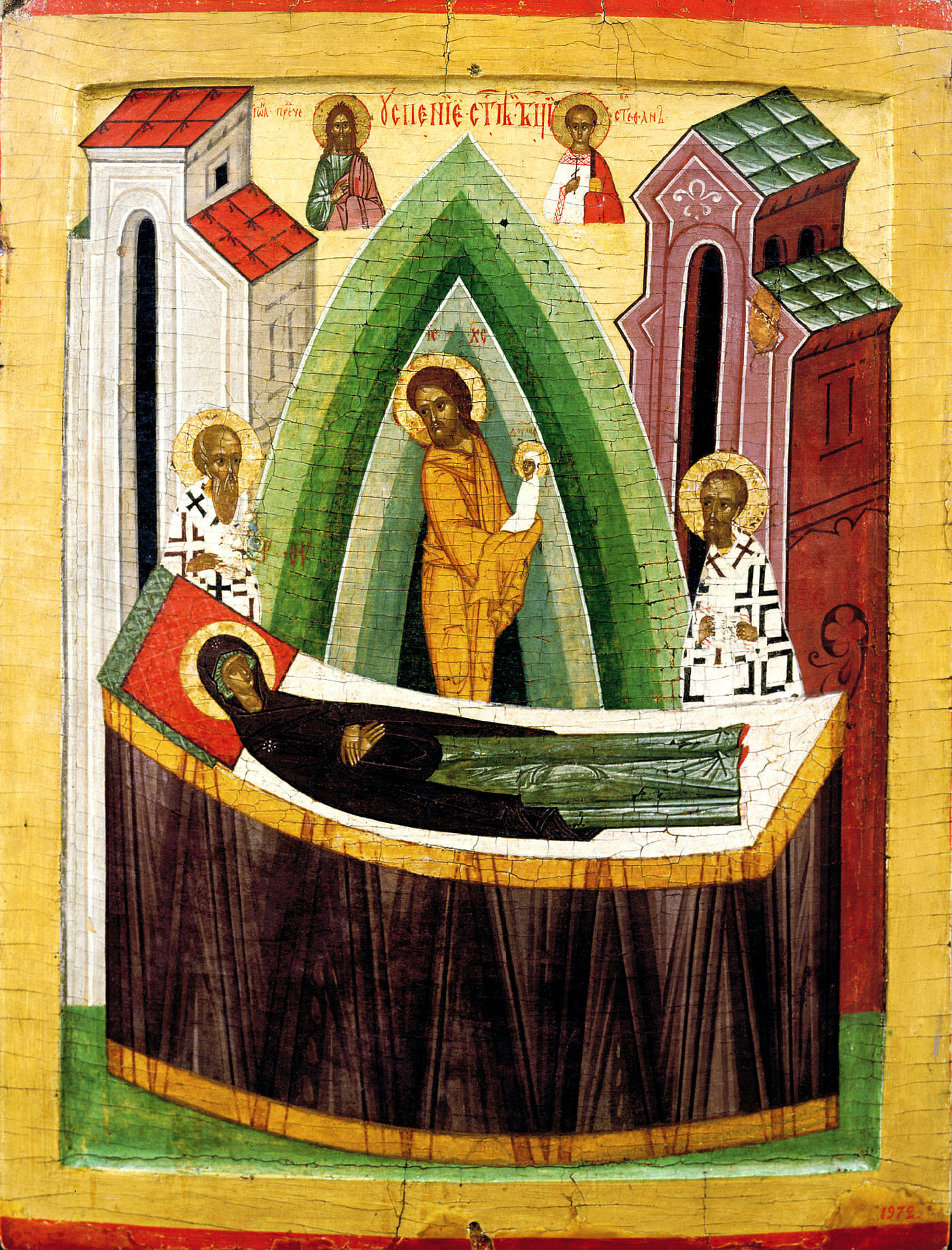

Dormition of the Mother of God. Icon. 15th century, Novgorod. Russian Museum, St. Petersburg.

In this work abstraction prevails.

It goes to show how broad of a range of stylistic variation can be found within what is commonly refered to as the “Byzantine style.”

It seems that if, on the one hand, the problem of the pioneers could be interpreted as an over-emphasis on “abstraction” or non-naturalism, as a means of conveying invisible realities; on the other hand, the attitude expressed by those who oppose them, tends to over-emphasize naturalistic verisimilitude, the depiction of the external form, as the definition of the icon. The truth is in the middle: the icon is both non-naturalistic and realistic. It reveals both the inner and the outer through its pictorial principles.

So likewise, mutatis mutandis, the “abstract” and “lifelike” tendencies in the Byzantine icon are not to be seen as necessarily mutually exclusive. As noted earlier, the term “abstraction” is to be understood in its etymological sense as an act of “drawing out” or retrieving something covered in order to reveal it. It should not be seen as implying a cold conceptualization having no concrete existence, or something lifeless and mechanical (as it is often the case in modernist abstraction). Rather, the iconographer always deals with the concrete, objective reality of living beings and persons. Therefore, you can have a stylistically predominantly “abstract” work that is full of life, vividness, vitality or enargeia.[xviii] The Byzantine painter in his pursuit of a “lifelike” depiction sought to capture the spirit of his subject. As Gervase Mathew says in Byzantine Aesthetics, “Reenacting the forms of Nature, art re-enacted their reality, not necessarily those surface phenomena which were fading into unreality precisely as they materialized…So again in portraiture…the artist is attempting to express through material detail the unique pneuma of each subject, his ‘Spirit and his Breath’.”[xix] In other words, capturing the pneuma and going beyond “surface phenomena” (abstraction) went hand in hand.

Mathew’s observation on the expression of pneuma or breath brings to mind the poem composed by the philosopher and poet Theodore Prodromos (c. 1100- c. 1158) commemorating an icon by his contemporary, the celebrated painter Eulalios. The icon depicts the Annunciation and T. Prodromos calls attention to how Eulalios managed to capture miraculously, through the Theotokos’ own intervention, her living breath, “You [O Virgin]…have let fall upon his brush a drop of breath.”[xx] Similarly, in T. Prodromos’ description of the depiction of the Archangel Gabriel, we are told how Eulalios was able to paradoxically convey speech through his brush, “Either the spirit has here taken on the grossness [of matter], or the colors have been altered in relation to the subject…the brush, as if it were made of some fine substance, delineates the incorporeal (aylian)… you are giving speech to the angel you have delineated, having dipped your brush in immateriality.”[xxi] Thus for the Byzantines what the painter sought to accomplish was not merely to “show” an external likeness but, rather, through this likeness the expression of invisible reality, the spiritual aspect of the subject depicted. Capturing “Spirit and Breath” was crucial in making an image “lifelike”.

A pertinent author to consult on the matter of illusionism vs abstraction and the “lifelike” in Byzantine art is Henry Maguire, who writes in, Icons of their Bodies: Saints and their Images in Byzantium:

Many modern critics have been puzzled by the Byzantines’ claims that their images were true-to-life and precisely resembling their objects, for viewers today tend to observe that Byzantine icons do not look “lifelike” at all…The difference between the present-day and the Byzantine viewer is not that of sophistication as opposed to naiveté, for no people have been more sophisticated in their approaches to images than the Byzantines. Rather, the difference is one of expectation. When a modern viewer speaks of an image being “lifelike,” the expectation is that it will be illusionistic, with realistic effects of lighting and perspective, like a photograph. The Byzantines, however, did not seek optical illusionism in their portraits, but rather accuracy of definition. Their expectation was that the image should be sufficiently well defined to enable them to identify the holy figure represented, from a range of signs that included clothing, the attributes, the portrait type, and the inscription. For the Byzantines, these features together made up a lifelike portrait.[xxii]

In the same text he analyzes the formal qualities used by the Byzantine iconographers to express corporality and immateriality, which can be seen as a parallel to the naturalism/abstraction dichotomy. This was done as a means to make distinctions between classes of saints, angels, monastics, Apostles, hierarchs, etc., and involved different degrees of flatness and volume, immobility or movement. As Maguire notes:

The Byzantines did not seek to make all their icons resemble modern photographic portraits, with all images displaying an equal degree of illusionism and spontaneity, but they did aim to distinguish between saints according to their types, so that some were shown with more, and some with less, modeling and movement. These distinctions were not absolute but relative. Within the formal range of a given artist or period, some classes of saints were given a greater freedom and three-dimensionality as a sign of their corporality, and some less.[xxiii]

Archangel Michael and the monk Archippus at Chonae. St. Catherine’s Monastery Sinai. First half of the 12th century. 37.5 x 30.7 cm.

In this icon we can clearly see the employment of two formal tendencies. On the one hand, the angel is depicted in swift movement, classical gracefulness and corporeality. On the other hand, St. Archippus is depicted more abstractly, utterly flat and still, as firm as the stone church behind him. The bodiless angel takes on form as he executes his task, whereas the bodily man becomes as if incorporeal in the attainment of dispassion.

For example, monks and ascetics were most often flattened and immobile to emphasize their attainment of apatheia (here we find abstraction), whereas soldier saints where more robust and in movement, as if ready to energetically strike with the sword at any moment and engage in physical prowess (here we find dynamic naturalism). Likewise, in the apse of Hagia Sophia, the enthroned Theotokos with the child Christ is depicted in robust corporeality, while the angels that flank her appear flattened and as if thinned out by light, almost merging to the gold background.[xxiv] Moreover, Apostles are usually depicted in clearly defined volume and three-dimensionality as a way of emphasizing their close proximity to Christ, that is, the Incarnation. Holy Bishops, on the other hand, often appear two-dimensional, their bodies virtually indiscernible under the abstract patterns formed by the many crosses on their vestments.[xxv]

St. Basil, St. Gregory the Theologian, and St. Cyril of Alexandria, 14th cent. Parecclesion of the Church of Chora, Constantinople.

Theotokos and Child Christ Enthroned, apse mosaic, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople. Here the Theotokos’ bodily presence appears unquestionably robust as compared to the archangel below. Not only the well modeled garments but also the suggested three-dimesionality of the he throne and stood help to accomplish this sense of strong corporeality.

Archangel Gabriel, apse mosaic, Hagia Sophia, 9th cent.

The solidity of Archangel Gabriel’s body seems to dissolve as the gold decoration in his garments, such as the large rectangle across his torso, becomes one with the background. In using the visual ambiguity caused by this figure/field interchange device, the iconographer captures the angel’s neither here nor there status between the noetic and corporeal worlds.

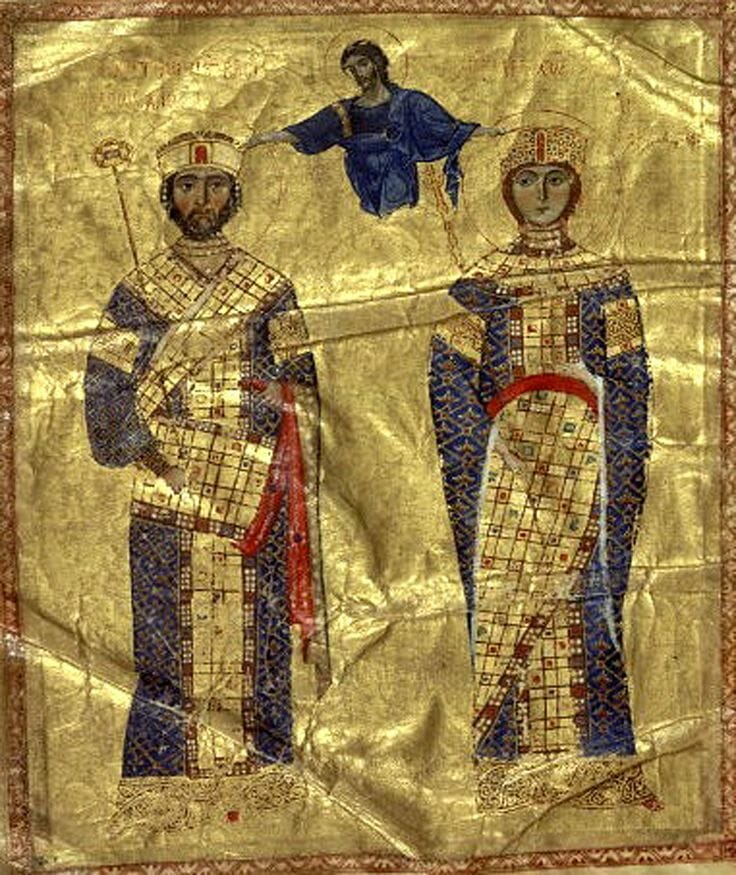

Coislin manuscript illumination of Michael VII Doukas and Maria the Alanian Crowned by Christ , from a collection of homilies of St. John Chrysostom, ca. 1072. Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, MS. Coislin 79, fol. 2bis v.

Or we can have an icon in which both abstraction and naturalism are present, such as the Coislin manuscript illumination of Michael VII Doukas and Maria the Alanian Crowned by Christ (Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, MS. Coislin 79, fol. 2bis v).[xxvi] Here we find the emperor and empress frontal, lofty, stiff, hieratic and flat, floating on a gold background. The ornamentation of their regalia further increases their “dematerialization.” However, from above, as if emerging from the gold, the Lord appears dynamically with outstretched arms in quarter view, his torso directed towards our left, his gaze looking towards the right. He is more palpable, corporeally defined and naturalistic, in comparison to the emperor and his wife. The implication of such juxtaposition is clear: here the formless Logos takes on form and enters temporality, whereas the emperor and his wife “put on” the attributes or participate in timeless divinity, beyond the constraints of corporality, as vicegerents of God on earth. As Maguire points out in Style and Ideology in Byzantine Imperial Art, the Coislin illumination stylistically parallels and calls to mind the encomium written by Psellos for Isaac Comnenos (reigned 1057-1059), in which he enumerates a series of epithets that exalts the emperor’s godlike stability:

You are an image of the signs of God. You are straight, true, stiff, exact, sweet, gentle, steadfast, firmly fixed, lofty,…a lantern of purity, a light-bringer of piety, an impartial judge, unwavering in judgement,…a secure counsellor, noble, unshaken in (stormy) waves.[xxvii]

John II Comnenos and Irene Making Offerings to the Virgin and Child,12th cent., mosaic in south gallery, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople.

This mosaic parallels the Coislin manuscript illumination. The Theotokos palpably enters the court, whereas the rulers appear less palpable under the elaborate regalia, as if gradually becoming one with the golden heavenly light.

It then starts to become clear how these characteristics enumerated by Psellos as “signs of God” can truly have equivalents in what is often referred to as an “abstract” pictorial style, having a potential to truly convey “a sense of the transcendent.”[xxviii] In other words, as mentioned earlier, the Byzantines were not merely attempting to “show” the outward form but, rather, through form symbolically conveyed meanings and suggested spiritual realities. And this fact in no way runs counter to the Byzantine notion of “lifelike” accuracy. Indeed, “abstract” pictorial tendencies were full of “lifelike” accuracy according to their standards. Therefore, we should be careful not to impose our anachronistic expectations of what constitutes “lifelike” onto the Byzantines in an attempt to discredit the intuitions of the pioneers.

To be continued…

[i] St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco, “Discourse in Iconography,” Orthodox Life, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Jan-Feb 1980), pp. 42-45. http://archangelsbooks.com/articles/iconography/DiscourseIcon.asp, (accessed 20 November, 2015).

[ii] T. Burkhardt, “The Foundations of Christian Art”, in: Sacred Art in East and West: Principles and Methods, Middlesex, Perennial Books Ltd., 1967, p. 70.

[iii] “In the modern search for pure art an attempt has been made to create an abstract art, without recognizable themes or forms, and having a symbolism devoid of all associations. Inasmuch as nothing exists disembodied, and there can be no spiritual experience which does not arise in some connection, all such attempts must be known as vain ambitions. Art, indeed, refers to the infinite: but it speaks of the infinite only when nature, the vehicle of the infinite, has been accepted in all reverence as the word by which God reveals himself.” A. K. Coomaraswamy-S. Bloch, “The Appreciation of Art,” in: The Art Bulletin, vol. 6, no. 2, 1923, p. 62; The work of the German art historian Wilhelm Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, from 1908, should be noted as having played a crucially influential role on many artists and art historians of the 20th century. Therein he looks at the whole history of art as a dialectical tension between two opposing psychological impulses expressed pictorially as abstraction and naturalism respectively. Here we find a distinctively modern nuance to the notion of abstraction as an escape from the dread of the “flux of being”, ultimately as “salvation” from Nature. In describing the impulse towards non-naturalism in art, Worringer writes that it sought to, “wrest the object of the external world out of its natural context, out of the unending flux of being, to purify it of all its dependence upon life, i.e. of everything about it that was arbitrary, to render it necessary and irrefragable, to approximate it to its absolute value.” Wilhelm Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, Hilton Kramer (trans.), New York, International University Press, 1953; originally published in German as Abstraktion und Einfühlung in 1908, p. 17; J. Trilling, Medieval Art Without Style? Plato’s Loophole and a Modern Detour, in: Gesta, vol. 34, no. 1, 1995, pp. 57-62.

[iv] To this list we can add Vladimir Lossky and Gregory Krug, who collaborated closely with Leonid Ouspensky in Paris.

[v] C. Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 312-1453: Sources and Documents, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2013, pp. xiv-xv.

[vi] St. John of Shanghai helps us contextualize the pioneer’s defense of the icon by looking back and giving us a summary of the detrimental effects wrought by Western secularization in the life of the Russian Orthodox Church during the Synodal period: “In certain respects, Russia’s acquaintance with the European West was very beneficial. Many technical sciences and much other useful knowledge came from the West. We know that Christianity has never had any aversion to knowledge of that which originates outside itself…Nevertheless, not all that was Western was good for Russia. It also wrought horrible moral damage at that time, for the Russians began to accept, along with useful knowledge, that which was alien to our Orthodox way of life, to our Orthodox faith. The educated portion of society soon sundered themselves from the life of the people and from the Orthodox Church, in which all was regulated by ecclesiastical norms. Later, alien influence touched Iconography as well. Images of the Western type began to appear, perhaps beautiful from an artistic point of view, but completely lacking in sanctity, beautiful in the sense of earthly beauty, but even scandalous at times, and devoid of spirituality. Such were not Icons. They were distortions of Icons, exhibiting a lack of comprehension of what an Icon actually is.” St. John of Shanghai, op. cit.

[vii] What the pioneers resisted was the crass naturalism of post-Renaissance painting. Although we here use the word crass, it has also been described as carnal naturalism. In other words, what we have in mind are those works of religious painting that, in spite of its sacred subject matter, employ a naturalistic manner of execution that betrays a sensual, sentimental and secular ethos. Of these kind of paintings St. John of Shanghai would say, “Images of the Western type began to appear, perhaps beautiful from an artistic point of view, but completely lacking in sanctity, beautiful in the sense of earthly beauty, but even scandalous at times, and devoid of spirituality.” Ibid.; However, we also find some instances of naturalistic paintings done in a wholly sober and pious manner, such as the renowned Theotokos of Valaam.

[viii] In order to make this point St. Photios the Great’s famous passage describing the mosaic of the Theotokos in the apse of the Hagia Sophia is often quoted, in which she is described as depicted so lifelike that she appears as though she is about to speak: “Such exactitude has the art of painting, which is a reflection of inspiration from above, set up a lifelike imitation…You might think [the Virgin] not incapable of speaking…to such an extent have the lips been made flesh by the colors.” Photios the Great, Homily XVII, Ar II 299, in: The Homilies of Photius Patriarch of Constantinople, Cyril Mango (trans.), Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1958, p. 290.

[ix] E. Kitzinger, Byzantine Art in the Making: Main Lines of Stylistic Development in Mediterranean Art, 3rd–7th Century, London, Faber & Faber, 1977, p. 9.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Speaking of the “renaissances” of the Byzantine period, L. Ouspensky notes, “The effect of these ‘renaissances’ was to introduce into this art the illusory and sensual character of pagan art, which is totally alien to Orthodoxy. Much later the same elements, artificially resurrected in the Italian Rennaisance, obtruded themselves into Church art under the guise of naturalism, idealism, and so forth.” L. Ouspensky, “The Meaning and Language of Icons,” in: The Meaning of Icons, G. E. H. Palmer and E. Kadloubovsky (trans.), Crestwood, SVS Press, 1982, p. 45.

[xii] What we will be referring to as the “Byzantine style” for the sake of convenience can perhaps be better understood as the traditional method or artistic system of icon painting encapsulating those pictorial principles that remain constant in spite of stylistic variations throughout the centuries. (See the section on Pictorial Principles below). More generally we take “style” to mean in the words of E. Fernie, a “distinctive manner which permits the grouping of works into related categories.” Or as E. Gombrich puts it, “…any distinctive, and therefore recognizable, way in which an act is performed or an artifact made or ought to be performed and made.” Art History and its Methods: A Critical Anthology, E. Fernie (ed.), London, Phaidon Press, 1995, p. 361; E. Gombrich, “Style” (1968), orig. International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, D. L. Sills (ed.), xv (New York, 1968), reprinted in Preziosi, D. (ed.), The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, Oxford, Oxford University Press,1998, p.150.

[xiii] As we will soon see, “naturalism” in the icon is better understood as “realism”. Moreover, what Kordis here refers to as “expressionism” is the directness of expression found in the abstract tendencies of late antiquity. G. Kordis, Icon as Communion, Caroline Makropoulos (trans.), Brookline, Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2010., p.51.

[xiv] Style can be subdivided into three categories, from narrow to broader, of distinctive manners of expression (tropos): individual (specific artists within a school), local (varieties of schools, i.e., Pskov, Novgorod, Moscow, Cretan, etc.), and religio-cultural (Byzantine vs. Renaissance). If we focus on the narrower definitions of style as pertaining to an individual or local school of iconography, it could be said that the theological import of style is hardly evident, since it may be dismissed as aesthetic idiosyncrasies found within one overriding Orthodox culture. Hence, some might consider it unwise to look for a theological correspondence or explanation for every single detail in stylistic variation. However, when we move into a much broader cultural context, and begin to consider the obvious differences between a Byzantine icon and a Renaissance religious painting, style clearly begins to bear more weight as an embodiment of a specific worldview, mentality or theology.

[xv] A. Hart, Beauty, Spirit, Matter: Icons in the Modern World, Herefordshire, Gracewing, 2014, p. 187; Here A. Hart echoes Photis Kontoglou who says: “Most people who are accustomed to seeing naturalistic art, that is, who are attached to phenomena, seek to find naturalism in Byzantine painting too. In reality, however, it expresses, with spiritualized forms abstracted from natural phenomena, a world which is beyond phenomena, a supernatural world.” (Our emphasis). P. Kontoglou, “Iconography”, in: Byzantine Sacred Art, C. Cavarnos (ed.), Belmont, Institute of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 1992, p. 90.

[xvi] St. John, op. cit. It is important to bear in mind that these first principles of the sacred art of the icon have never been contested by the Church as contrary to Tradition, were the ones accepted as a guide by the pioneers, and, as we are about to see, do not contradict the Byzantine notion of the icon as “lifelike”.

[xvii] A. Hart, op. cit.; Kordis also points out, “Byzantine artists do not think in naturalistic terms, deploying the coordinates of time and space to create a composition.” (Our emphasis). G. Kordis, op. cit., p. 48.

[xviii] See C. A. Tsakiridou, Icons in Time, Persons in Eternity: Orthodox Theology and the Aesthetics of the Christian Image, Farnham Surrey, Ashgate, 2013, pp. 49-71.

[xix] G. Mathew, Byzantine Aesthetics, NY, Harper & Row, 1971, p. 159

[xx] C. Mango, op. cit., p. 231.

[xxi] Ibid.; C. A. Tsakiridou notes: “The language of Prodromus suggests an eye sensitive to aesthetic qualities. The emphasis on eloquent liveliness of form, the idea of capturing an object in its act or moment of conscious existence, recalls the Ch’an concept of chi’yun or ‘spirit resonance’.” C.A. Tsakiridou, op. cit., p. 237.

[xxii] H. Maguire, Icons of their Bodies: Saints and their Images in Byzantium, New Jersey, Princeton University Press,1996, pp. 15-16. What is important about Maguire’s approach is that he always backs up his claims not only with concrete, multiple examples of icons, but also with the ekphrasis that were often composed to accompany them or written in praise of the saints depicted. These ekphrasis, enumerate the attributes of the saint very clearly, in such a way that we can find their equivalents as visually articulated in the icons.

[xxiii] Ibid., p. 49.

[xxiv] “The mosaic of the Archangel Gabriel in the apse of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, for example, differs from the mosaic of the Virgin and Child it flanks; in contrast to the Virgin, and even to the infant Christ, whose limbs are well modelled by shade and whose bodies are firmly set upon a three-dimensional throne, he angel appears thinned out by light and gold ̶ the gold ground gives no indication of spatial setting and the unbroken sheets of gold in the costume dematerialize the form.” M. Maguire, “Style and Ideology in Byzantine Imperial Art” in: Gesta, Vol. 28, No. 2, 1989, p. 223.

[xxv] M. Maguire, op. cit., 1996, pp. 48-99.

[xxvi] M. Maguire, op. cit., 1989, pp. 217-231.

[xxvii] Ibid., p. 224.

[xxviii] A tendency towards the geometric is one among many of the features which make up an abstract style and gives a “sense of the transcendent,” as Fr. Maximos Constas puts it. As to how geometry has played a role in the philosophy of Plato and the icon see Fr. M. Constas, The Art of Seeing, Alhambra, Sebastian Press, 2014, pp. 178-180; On the one hand, some forms of naturalism can be described as “carnal”, as pointed out by the pioneers, in the sense that they induce desire. On the other hand, abstraction and or a tendency towards geometry, can be described as “spiritual” in the sense that it focuses our attention on the “intelligible” apprehension of the subject depicted, rather than on its sensible perception. The former implies flux, vacillation, unmeasured pathos; whereas the latter implies, stillness, stability, measure according to logos/ratio.

Thank you, Father Silouan, for this well-researched article. Your scholarship is appreciated.

Thank you, Father Silouan, for crafting such a splendid article. The tension between abstraction and ‘naturalism’ within the icon tradition is an extremely important and current issue. It is a subject that needs to be addressed dispassionately, with assertions backed by examples, and this you do superbly. This debate is important not least because a sound theological and aesthetic foundation is required if we are to see an authentic iconography develop in our times, one that is neither copiest nor with innovations discordant with life in Christ.

Aidan Hart

Thank you Father Silouan, for your insight, authority and clarity. Your contemplations – and your ability to communicate in words as well as in your art are a timeless and priceless gift to me as an aspiring contemporary iconographer with a Fine Arts background, working on my MFA. Thank you again for bringing your insight, research and experience into the light. Your work helps me continue to find my place, thank you again. Grateful to OAJ for continuing this resource and to my priest, Fr Antoni Perdomo in Pharr, Texas for introducing this resource to me years ago.