Similar Posts

A Tough Love

Many are drawn to the beauty of icons. But clearly this beauty is of a different order than, say, that of a Greek statue, or of a Renaissance painting. Icons are liturgical objects, created for prayer, a means of communion with the Lord. So what are some of the characteristics of divine beauty, and what implications does this have for how icons are painted?

Icons: veneration and transformation

Icons fulfil two complementary roles. Their primary role is to connect us to the holy persons whom they depict by bearing their name and likeness. We honour the saints through their icons. The way we wish to treat the saint is expressed in the way we treat their image – we kiss the saint by kissing or venerating their image.

But the icon has another, complementary, role, and it is this that most concerns the nature of beauty. This function is not so much to do with what is depicted as how the subject is depicted. It is what we might call the transformative power of the icon. Even those who don’t understand their subject matter seem moved by well-painted icons. Why is this? We say icons are beautiful, but what is meant by beauty? Does this beauty change us of itself, or not? What is the consequence of an experience of beauty? Are there different types of beauty, some higher than others? Is there even a false beauty? We cannot answer all these questions here, but we can at least consider some features of liturgical beauty.

Beauty will save the world. But what beauty?

Many of us have heard the quote from Dostoevsky’s book The Idiot that “beauty will save the world”. This is perhaps true. But we do need to read the whole conversation in the book to get the fuller picture, for this statement is soon followed by the question: “But what beauty?”

The quote comes from the mouth of the rather unpleasant young man Hippolyte, who is dying of tuberculosis. He is speaking to Prince Myshkin, the central, and in many ways Christ-like, figure of the novel. Hippolyte follows on to ask Myshkin: “Is it true, prince, that you once declared that ‘beauty would save the world’?” The Prince listens attentively, but doesn’t reply, so a little later Hippolyte continues to question him: “… What beauty saves the world?” Hippolyte clearly thinks that the answer to his own question is something to do with God, for immediately he goes on to say: “Colia told me that you are a zealous Christian. Is it so?”. Hippolyte clearly thinks there is something divine about this beauty that can save the world.

Prince Myshkin doubtless agrees. But for him beauty is not soft. It is also a tough love, for when Hippolyte demands more champagne the Prince says: “’No, you’re not to drink any more, Hippolyte. I won’t let you”, and he moves the glass away. The subject they are discussing is holy ground, so Myshkin is telling Hippolyte not to mess with it.

Perhaps then in answer to Hippolyte’s question, “But what beauty will save the world”, there are not different types of beauty but different uses of beauty. A graphic designer can misuse the principles of beauty to entice us to buy things that we don’t need, while the principles themselves remain inviolable.

Mosaic of Theophany in Hosios David, Thessaloniki

Terreauty: the awesomeness of divine beauty

A good starting point to regard beauty might be angels. Presumably, angels are beautiful, for they are sinless creations of God. So what does the Bible tell us happens when people encounter an angel? They are usually terrified, so the first words of angels to people often have to be “Don’t be afraid!”

For example, when the prophet Ezekiel had his vision of heavenly worship, what was his response? “So when I saw it, I fell on my face” (Ezekiel 1:28).

Mary was “greatly disturbed” at the words of the angel Gabriel, who had to calm her with the words: “Fear not, Mary”. On meeting the angel at Christ’s empty tomb the myrrh bearers “became terrified and bowed their faces down to the earth” (Luke 24:5). And Samson’s mother tells her husband after her visitation by an angel: “A man of God came to me and his appearance was like the appearance of the angel of God, very awesome.” (Judges 13:6).

C.S. Lewis coined a word to describe this union of terror and beauty: terreauty.

So divine beauty reveals something much greater than ourselves. It is sublime rather than comfortable. It possesses a shock element, disturbing and awakening us. It unites seeming opposites: it is attractive and terrifying; it is homely and adventurous; it invites and sends; it is measured and immeasurable; pleasurable and demanding.

This alarm or even terror when confronted by the awesomeness of divine beauty can be seen as a form of veneration, an acknowledgement of its otherness. In his book ‘Till We Have Faces’, C. S. Lewis has Orual describe what it was like to hear Cupid’s voice:

… in its implacable sternness it was golden. My terror was the salute that mortal flesh gives to immortal things.

Awe before the awesome God is a form of worship.

When faced with a choice between two things, we usually choose what appears to be most attractive. Because therefore the unknown is often fearsome, divine beauty remains attractive enough to encourage us to step forward into the unknown.

But this choice is not always straightforward. Some things appear attractive in the beginning but quickly go sour, while eternally good things can initially be bitter to the tongue. A martyr is the ultimate example of this. He or she seeks the bliss of the long term and for this is ready to sacrifice the comfort of the short term.

The word martyr, of course, means witness – someone who has seen something. A martyr must first have seen or experienced enough divine beauty for he or she to choose the greater beauty of God over their own life.

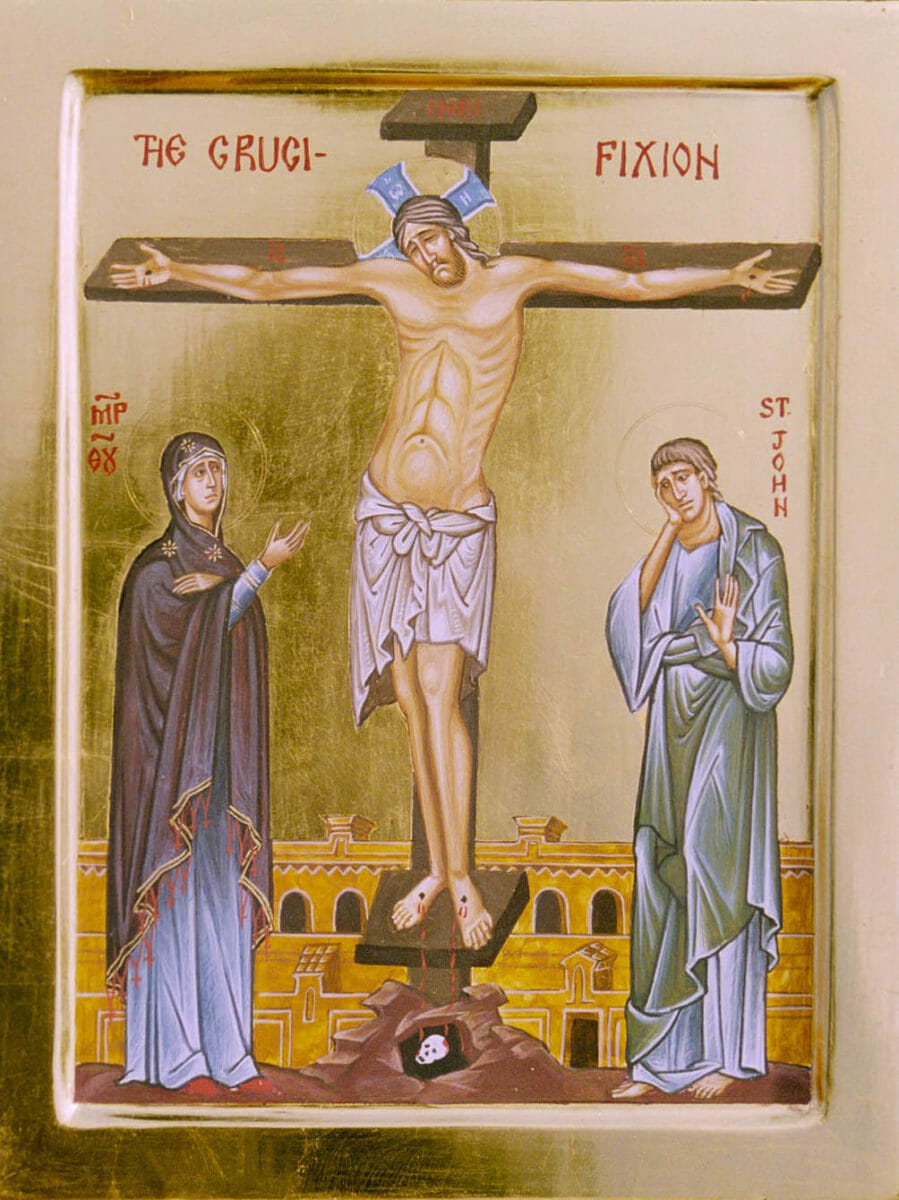

So beauty must lead us through and beyond the immediately felt or seen. After all, the greatest disaster that the world has known – the crucifixion of the Son of God – has also become the greatest saving event of all time. But to see this requires spiritual insight, to see beyond the immediately apparent spectre of a body on a cross.

Beauty and decision time: Grapes from the Promised Land:

This leads to our second observation: one role of beauty is to give us a foretaste of that for which we suffer and labour. Aesthetic beauty intimates the prize of our asceticism. It shows us the trophy for which we compete.

Beauty can also be likened to the massive bunch of grapes that the scouts brought back from the Promised Land to their fellow Israelites still wandering in the wilderness:

And they came to the Valley of Eshcol, and cut down from there a branch with a single cluster of grapes, and they carried it on a pole between two of them; they brought also some pomegranates and figs. (Numbers 13:23).

This enormous cluster of grapes was meant to assure the Israelites that it was worth making the effort to possess the lands, that the land of Cana was as abundant as God had promised.

However, this beautiful sign was not enough of itself. It was an assurance, but could not compel the Israelites to act. As it transpired, every one of them except Caleb said that the Canaanites were too big to overcome, and so they could not possibly go up and possess the land. As a consequence God promised that of them all only Caleb and Joshua would enter the Promised land, while the rest would perish in the wilderness. Beauty beckons, but does not compel.

The fruits of the Promised land demanded a decision: believe and act and venture out, even against odds, or remain where you are. It is the same with beauty. It is but a promise of something greater. It is fruit from a tree, but not the orchard itself.

This surely is one reason why the first icon that a fully trained iconographer traditionally paints is of the Transfiguration. The Transfiguration event occurred a few days before Christ’s Crucifixion, so that the disciples would not completely lose heart when Christ was crucified. Our task as icon painters is similarly to give the faithful a foretaste of God’s glory in and through creation, so that we can remain with Christ throughout our struggles and suffering. An icon strains to show events prophetically, to discern God’s action through them. It shows the world and its events as a bush burning but not consumed, and not as a mere bush.

So true beauty creates a crisis. Like a meeting with an angel, we are awed, but the angel then speaks to us and usually asks something of us, something to believe or something to do. An encounter with beauty, therefore, leads us to a threshold, and then we must decide. Beauty does not change us; it leads us to the threshold of change, at which point we must say yes or no.

Transfiguration (by the author)

This is confirmed by St. Maximus the Confessor, who wrote that the tree of knowledge of good and evil represented all of creation. If we decide to receive creation’s fruits with thanksgiving, he asserted, they become for us knowledge of good. Such a eucharistic life would have prepared us to partake of the Tree of Life, who is Christ Himself. Thanksgiving for created beauty leads to deification by divine beauty. If on the other hand, we decide to be mere consumers, partaking of the world thanklessly, then our life becomes for us death and knowledge of evil.

Nicodemus the Agiorite, the compiler of the Philokalia, confirms this central role of choice when he wrote in the preface of his work:

[God] thus made man a watchman over the material creation and an initiate of the spiritual, according to Gregory, the great theologian. What indeed was man? Truly, nothing other than an image and a full Icon of all graces created by God. God then gave him the law regarding His order, as a test of freedom …. If man kept order, he was to receive as a reward the enhypostasized grace of deification, becoming god and so radiate pure light for all eternity.

The beauty of Eden was the setting for this all-important choice: Shall I obey and love the One who created all this splendour, or shall I grab the gift and run? Shall I embrace the Creator in and through His creation, or shall I take the gift and turn my back on the Giver?

This leads us naturally to the next observation: divine beauty and the word go hand in hand.

Beauty and the Word

Divine word and divine image have the same source, the Logos, the Word of God who expressed the glory of the Father through the Spirit. When the apostle John used the term Logos to describe the second Person of the Trinity, he undoubtedly had in mind the meanings given it by the Greek Stoic philosophers and the Jewish Philo of Alexandria. For them, and John, the term logos signified not only word but also the animating and ordering principle of the cosmos. John was saying that Christ the Logos reveals the Father as both speaker and artist, both orally and visually.

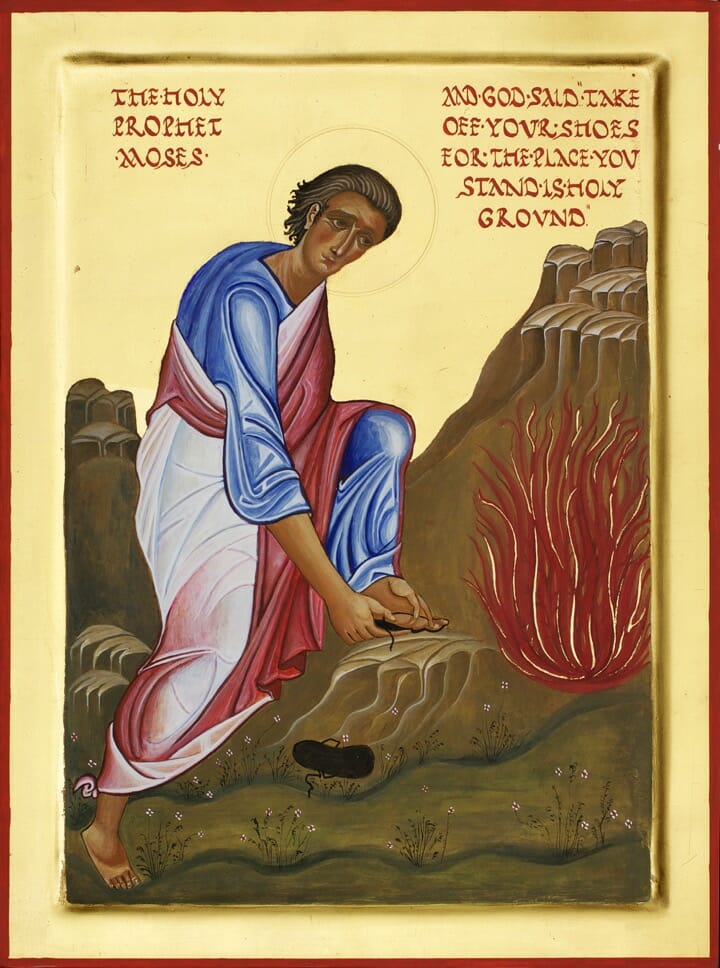

This pairing of word and image is nowhere more graphically expressed than in Moses’ encounter with God at the burning bush. What happened when Moses drew near to the bush that burnt without being consumed?

[Moses] led the flock to the far side of the wilderness and came to Horeb, the mountain of God.2 There the angel of the Lord appeared to him in flames of fire from within a bush. Moses saw that though the bush was on fire it did not burn up. 3 So Moses thought, “I will go over and see this strange sight—why the bush does not burn up.”

4 When the Lord saw that he had gone over to look, God called to him from within the bush, “Moses! Moses!”

And Moses said, “Here I am.”

(Exodus 3:2-4).

First there is the visible, and we could say beautiful, phenomenon of the burning bush that draws Moses’ attention. He sees something mundane – a bush – combined with something transcendent, the fire. He then moves towards it. God sees that he is attracted to the bush, which is what He had intended. He then speaks to Moses from out of the bush. Moses answers. Then God introduces Himself. “At this, Moses hid his face, because he was afraid to look at God.”

As we know, God goes on to tell Moses that through him He will deliver the Israelites from bondage and lead them into the Promised Land.

In like manner, the visual beauty of the icon cannot be separated from the Word. Beauty attracts us to the good, while the Word tells us how we can become good. Goodness and beauty is all to do with relationship, and relationship requires communion, speaking with the other, knowing the other person’s will. Often we are first drawn to someone because we find them attractive. The next stage is to deepen this first bond by talking with them, communing with them.

I like to think of beauty as a wonderful fragrance that wafts to us over the high wall of an enclosed garden. We are walking by and smell this scent. We want more. We want to find its source, but don’t know how to get into the garden. So we ask around and eventually someone guides us to the entrance. The Word leads us to the source of the sensed beauty.

We can think of icons as a true myth in the original sense of myth. Mythos is a Greek word that means something transmitted by word of mouth, such as a fable, legend, narrative, story, or tale, especially a poetic tale. A mythos is thus transmitted as a living thing by word of mouth rather than by writing. This means that it needs a personal relationship to transmit it, rather than an apersonal book. Icons similarly are part of a living tradition. Even the Bible itself, though written, was always meant by the Church to be experienced and interpreted within the living life and tradition of the Church. The Bible is within and not over the Church. The icon likewise exists within the Church.

Because of this personal element in beauty there is also the element of timing. Good storytellers have consummate timing. They know when to introduce characters, how to set the scene to draw in the listener. The whole story of Moses meeting God in the bush shows how consummate is God as a story maker, how He leads Moses step by step to agree to do the impossible.

In fact, one of the Greek words for beautiful suggests timeliness. It is ὡραῖος (hōraios), an adjective etymologically coming from the word ὥρα, hōra, meaning hour. This word suggests that something is beautiful because it is timely. It is attractive not just because everything is in its right place, like a well-composed painting, but also because everything is in its right time.

This is why icons are liturgical. They are most effective when they are encountered in the right time and place. They are created to be part of the sung worship of the Church, processed and venerated at particular times and seasons. Festal icons in particular are best experienced in the context of the hymns created specifically for their respective feast. The texts interpret the icon and the icon interprets the texts.

Whenever God speaks to us we are challenged to change, to progress even further into His mercy and goodness. Beauty dies as an unfertilized flower if we do not, through it, plunge deeper into its divine source. Icons therefore call us to repentance and transformation, which is our next point.

Beauty and repentance

To repent means to change the way we see things, and thereby to change the way we act. The Greek word metanoia means literally a change of nous, and nous in patristic writing denotes the eye of the heart. Basically, repentance is to turn from seeing the world and ourselves as opaque, to seeing God in all. It is to change from being a consumer to being a worshipper, from being a robber to being eucharistic.

St. John Chrysostom affirms this need to see the beauty of the world sacramentally and eucharistically when he writes:

The sky is beautiful, but it is so in order that you may bow down before Him who made it; the sun is bright, but it is so in order that you may worship its author; if you stop at the wonder of creation and get stuck at the beauty of these works, the light will become dark for you, or rather you will have used the light to change it to darkness.

The particular beauty of icons can help us make this change by altering the way we see the world. How can it do this?

Perhaps the most obvious way is the strange perspective systems that icons use. They disquiet us from our ego-centric world view.

A building, for example, is often depicted as viewed from many vantage points at once – from God’s point of view rather than from our mono-view.

Or persons further away might be shown larger than those nearer. The icon is thereby showing us that in love there is nothing distant.

Or again, the so-called inverse perspective which has the vanishing point in front of the icon rather than behind, subliminally suggests to the viewer that not only are we contemplating the subject, but that the subject is contemplating us. We are the vanishing point from the perspective of the holy person depicted.

Furthermore, the very flatness of the icon compels us not to rest in its beauty. This deliberate imperfection is a constant reminder that the icon is an image of something archetypal, something higher, something more real than itself. Beginning with itself, the icon tradition invites us to see all creation, all events, in this divine and transparent way. Presumably in the age to come we shan’t need icons for we shall directly know the archetypes themselves.

by Fra Angelico, 1434 AD

In an address to artists given in the Sistine Chapel, Pope Benedict XVI said:

Beauty, whether that of the natural universe or that expressed in art, precisely because it opens up and broadens the horizons of human awareness, pointing us beyond ourselves, bringing us face to face with the abyss of Infinity, can become a path towards the transcendent, towards the ultimate Mystery, towards God.

Love’s labour: by foot or by mouse?

Love’s labour: by foot or by mouse?

But how can we create such beauty? This leads us to our next point: the skill to paint icons requires hard work. Perhaps the greatest iconographer of our times, Archimandrite Zenon, said that 20,000 hours – that’s ten years! – are required to become truly proficient. Jacob wrestled all night with the angel before being blessed. The Israelite spies had to actually walk to the Promised Land to bring back the bunch of grapes. The grapes of divine beauty are gained by long labour and not from Amazon by the click of a mouse.

But labour is required not only to acquire the artistic skill: Ascetic struggle is also needed for the iconographer personally to know divine beauty.

Painting an icon is like composing. The process requires thousands of little decisions. If we have the music of heaven in our souls then we can measure each choice against it: Will this or that colour harmonize with this sublime music inwardly heard? Ultimately, the canon of iconography is the life of the Holy Spirit within the iconographer and the Church.

Perfect imperfection

But even with this experience and skill it is not always easy to interpret the kingdom of God in colour and form. The iconographer has continually to remember the ultimate aim of his or her ministry: to lead the viewer to the saintly person whom they are painting, and to help them to become beautiful saints themselves. Ironically, great icons sometimes use unattractiveness and imperfection to achieve this aim. Beauty is at the service of love, and love is not only expressed in outward loveliness. Sublime beauty is not equivalent to aesthetic delectation.

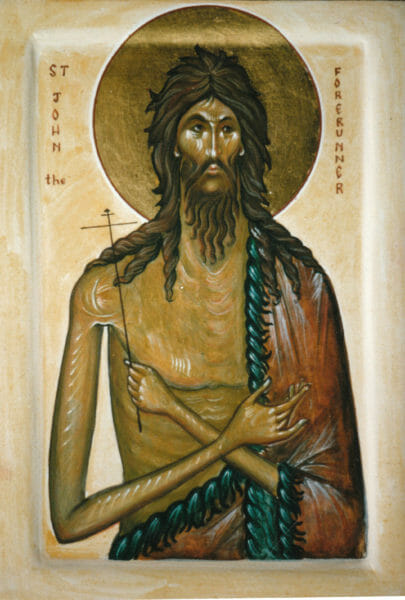

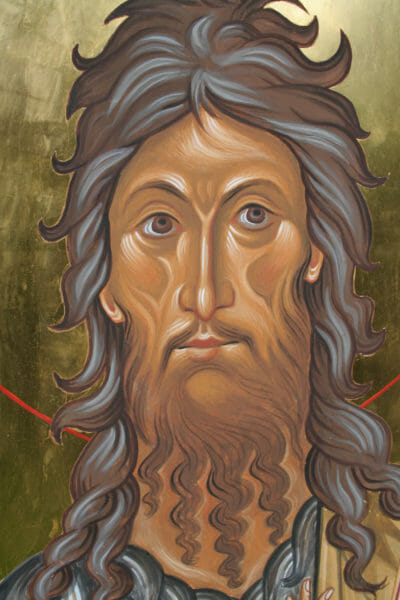

Take for example icons of St John the Baptist. He is sometimes shown with emaciated limbs, arms with hairs like nails, and sunken cheeks. Yet his face is noble, compassionate. He prays for us although he himself suffers. He has suffered and died and yet he lives now in Christ. His unattractive outward form concentrates us on the nobility of his actions and his prayer for us.

The only way the icon painter can avoid sentimentality, and know when to use imperfection and unsightliness effectively, is to know divine beauty personally.

So true beauty is incomplete. It attracts us, and then leads us beyond itself, to its source.

It is a fragrance, but not the flower. The beauty of God’s creation is so often designed to excite action. In the case of the flower, its attractiveness exists to attract insects so that they can fertilize it with pollen from another flower. The flower then dies to become something much plainer – a seed – but something with even more promise.

It is a fragrance, but not the flower. The beauty of God’s creation is so often designed to excite action. In the case of the flower, its attractiveness exists to attract insects so that they can fertilize it with pollen from another flower. The flower then dies to become something much plainer – a seed – but something with even more promise.

This idea of perfect imperfection is epitomised in the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi. This is a composite expression that combines the themes of peace, tranquillity, and stillness – the sort of thing one might experience while alone in nature (wabi) – with the idea of something aging with grace, where scars become proof of experience (sabi), where the patina of wear and tear is the sign of loving use. This aesthetic emphasizes authenticity and honesty, particularly honesty about the transience of life. It acknowledges the presence of suffering and mortality.

This idea of perfect imperfection is epitomised in the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi. This is a composite expression that combines the themes of peace, tranquillity, and stillness – the sort of thing one might experience while alone in nature (wabi) – with the idea of something aging with grace, where scars become proof of experience (sabi), where the patina of wear and tear is the sign of loving use. This aesthetic emphasizes authenticity and honesty, particularly honesty about the transience of life. It acknowledges the presence of suffering and mortality.

One expression of wabi-sabi is the repair of a loved piece of pottery. The repaired cracks are made a feature, even sometimes gilded. The repair is at one and the same time beautiful and a reminder of the pot’s once pristine state.

Japanese bowl – example of Wabi-Sabi

On a lighter note, I have on the wall of my studio a humorous take on this idea of graceful aging. It shows two elderly Victorian men, moustached and dressed with formal dignity. The caption reads: “Men do not grow old, they just become more important”!

This concept of perfect imperfection leads us to our final observation: that created beauty is intended to lead us towards union with God himself, the first Beauty.

Beauty and Union

Divine beauty is reflected in created beauty, but at the same time infinitely surpasses it. Created beauty, being created, is insufficient for the human soul made in God’s image. It is an entrée, and not the full meal. It makes us desire more, to find and commune with beauty’s Source.

The Scriptures begin with Adam and Eve in Eden as a sort of betrothal, and end with the marriage of Christ with His bride in the New Jerusalem. The Bible opens with an account of creation, including the creation of the sun, water, animals and a garden. All these things are real and to be valued, but at the same time they are each one icons of a yet more essential beauty. So the Scriptures begin with the creation of these icons, and end with the New Jerusalem in which we meet the archetypes. In Revelation chapter 22, the Apostle John describes to us this city:

Then the angel[a] showed me the river of the water of life, bright as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb 2 through the middle of the street of the city. On either side of the river is the tree of life[b] with its twelve kinds of fruit, producing its fruit each month; and the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations. 3 Nothing accursed will be found there any more. But the throne of God and of the Lamb will be in it, and his servants[c] will worship him; 4 they will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads. 5 And there will be no more night; they need no light of lamp or sun, for the Lord God will be their light, and they will reign for ever and ever.

The water of Genesis is shown to culminate in the water of life, lambs in Christ who was slain for us, and trees in the Tree of Life. Even created light and the sun itself need be no more, for the Lord God Himself will the Light of the righteous.

So the beauty of paradise was a promise of our union with Beauty Himself. It was the first call of creation for its Maker. Creation is a single yearning prayer of the bride for the Bridegroom: “Come Lord Jesus!”

But between this first prayer of creation and the Bridegroom coming down out of heaven is the tough love of the Lamb of God, who suffered for the Bride and was slain for the Bride. The Bridegroom comes toward us through suffering, and we too must journey toward Him through suffering. It is a synergy of God with created gods:

The Spirit and the bride say, ‘Come.’

And let everyone who hears say, ‘Come.’

And let everyone who is thirsty come.

Let anyone who wishes take the water of life as a gift.

…The One who testifies to these things says, ‘Surely I am coming soon.’

Amen. Come, Lord Jesus! (22:17,20)

I think beauty always has an element of the nostalgic and yearning, for it reminds us of our homeland, who is Christ, Who is ‘the land of the living’. As St. Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain wrote in his preface to the Philokalia:

But if [God] is called Beautiful, it is in the sense that He both contains all that is beautiful and surpasses all beauty.

We are all called to union with God, and not merely to follow Him at a distance. As the Apostle Peter wrote in his second epistle:

His divine power has given us everything we need for a godly life through our knowledge of him who called us to his own glory and goodness. 4 Through these he has given us his very great and precious promises, so that through them you may participate in the divine nature, having escaped the corruption in the world caused by evil desires. (2 Peter 1:3,4)

Peter knew what he was talking about, for he had experienced this glory and beauty on the mount of Transfiguration, and then even more fully at Pentecost. This call to deification is why most of the Church’s year is defined by Pentecost – the sixth Sunday after Pentecost, and so on. The Holy Spirit is not given to us merely as a sort of petrol to fuel our activities. The Holy Spirit comes to us and dwells in us as God Himself. We commune with Him and He with us.

Beauty and Glory and Light are inextricably linked. They are names of God. They are characteristics of the Divine Nature in which we are called to participate. The great Russian writer, Feodor Dostoyevsky, wrote that “the Holy Spirit is the direct seizure, the grasping of Beauty”.

I said earlier that created beauty stimulates nostalgia. In fact, many of the fathers speak of desire for God as inebriation. We have a sip of this wine, the Spirit of God, and we want more. One of the Fathers, I think either Gregory of Nyssa or Isaac the Syrian, writes of the soul that is not satisfied with drinking from the cup, so it seeks out the barrel. Then it finds that it still can’t get enough wine even by drinking directly from the barrel tap, so it seeks the vat itself, the source of the wine, and throws himself into the vat. We want God inside us and us to be inside God. This is why we have gold haloes and assist in icons, and gold backgrounds. This gold suggests God in us and around us.

We possess life, but God is Life itself. We can be good, but God is goodness itself. Returning to the narrative of Moses and the burning bush, when Moses asked God’s name, the Lord replied:

God said to Moses: “I am the existing one. This is what you are to say to the Israelites: ‘I AM has sent me to you.’” (Exodus 3;14)

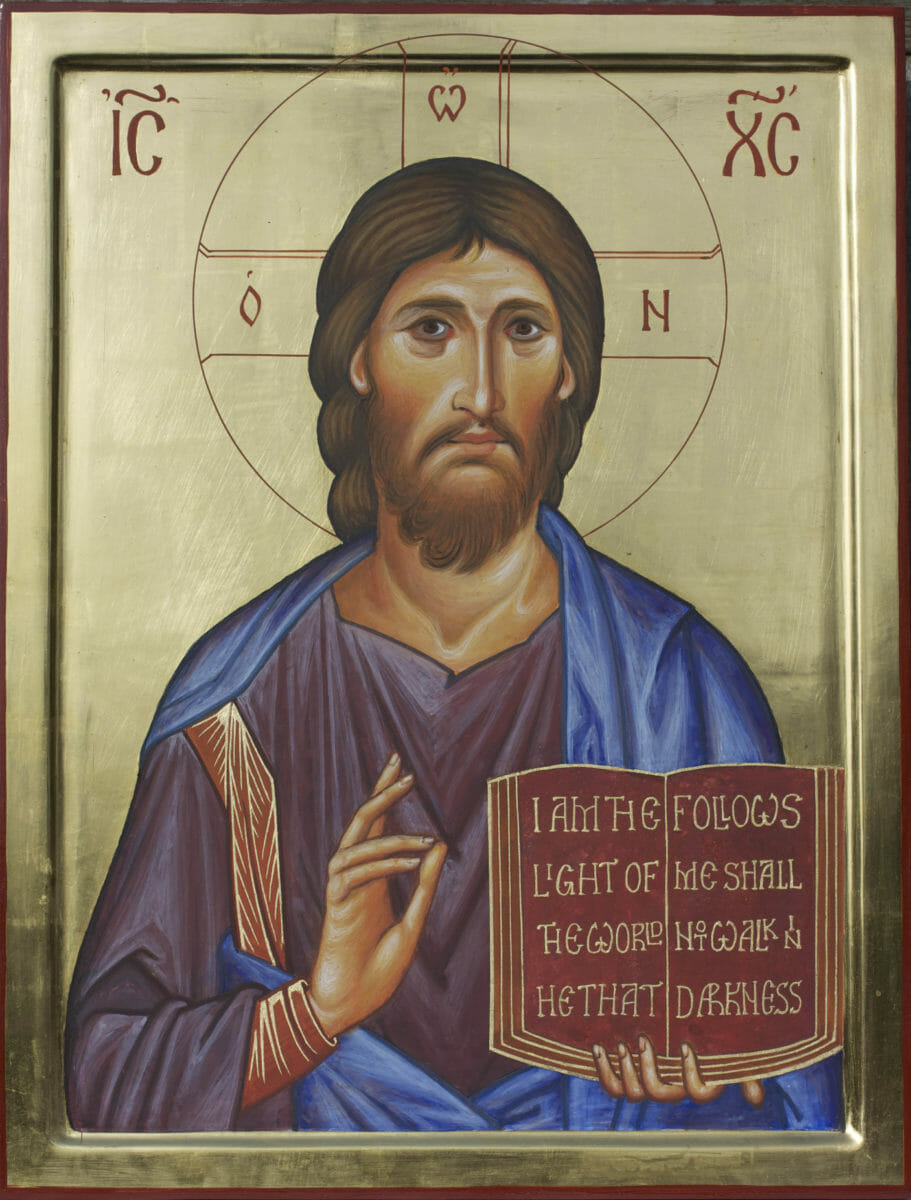

The Septuagint Greek translation of this verse is ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ὤν, ego eimi o hon, which literally translated reads: “I am the existing one.” We have, but God alone is. And what we have draws us toward union with Him Who Gives. This is why the words ὁ ὤν are often inscribed within Christ’s halo.

But union with this glory and beauty is only gained through the Cross and Resurrection. The words ὁ ὤν are indeed inside the halo of Christ’s divinity, but they are inscribed within a cross. The fertilized flower must die to produce seed and a new plant.

So the Cross lies between Eden and the New Jerusalem, between witnessing divine beauty and union with divine beauty. Beauty can save the world, but only through fire.

1 Talk at the British Association of Iconographers, 17th November, 2018, St Saviour’s Church, Pimlico, London.

2 The Idiot by Feodor Dostoevsky, translated by Eva Martin, pub. Global Grey eBooks, 2018. Page 414.

3 C. S. Lewis, Till We Have Faces (San Diego: Harvest/HBJ, 1984), p. 171.

4 John Chrysostom, Sur la Genève, Sermon I. SC 433, Paris, 1998, p. 145. Trans into English by Archbishop Job of Telmessos.

5 Pope Benedict XVI, Meeting with Artists, an address given in the Sistine Chapel, 21 November, 2009.

6 Quoted in Paul Evdokimov, The Art of the Icon: a Theology of Beauty, trans. Steven Bigham (Redondo Beach: Oakwood Publications, 1990), page 2.

A wonderfully informative and uplifting article. Thank you.