Similar Posts

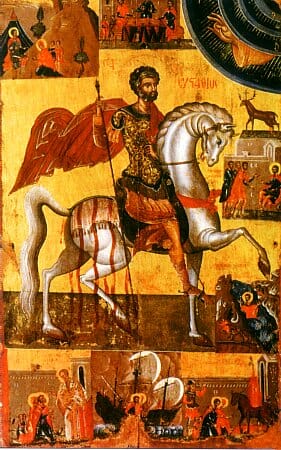

Iconography often shows remarkable events from the lives of the saints, as here St. Eustace sees a stag with a cross between its antlers.

One of my most vivid recollections in Berkeley was a class with Dr. A. T., the quintessential absent-minded professor. Thick glasses, messy hair like he just got out of bed, unkempt mustache. He wore the same ratty sport coat every day, and it had one pocket that was always just a little bit ripped off. His disheveled appearance seemed organically to merge with his general disdain for anything traditionally perceived as sacred.

During a “Russian, Eastern European, Eurasian Cultures” class we were reading the life of Prince Vladimir of Kiev. Dr. T. scoffed, along with all the rest of the students, at the mere suggestion that Prince Vladimir became a monogamist after his conversion to Christianity. The possibility of “suffering a sea change” was not even considered by these people. Not surprising, perhaps, in a college environment where excess is the banal norm, but that’s not what struck me the most. In my rather sheltered Orthodox existence, it was my first time encountering the idea that the Lives of the Saints are in some sense “not true”.

This shouldn’t have surprised me – the fact is that stories of the saints are often historically anachronistic, they routinely contain events of the most fantastic nature, hard even for some faithful Christians to accept, they repeat common motifs or “tropes”, they brazenly loot from mythology and popular legend and some of them are, to put it bluntly, not very well written. Leaving behind this last point for the present, the others may seem to be compelling enough to suggest that there may be a pink elephant in the room. If we know that certain elements in lives cannot possibly be historically accurate, should we not do something about it? If dragons routinely appear in the Lausaic History, shouldn’t its reading be banned from the services of Lent, for example?

This sort of thinking presupposes that historical truth is inherently verifiable and objective – like the natural sciences – a very popular way of looking at history, because it promises the exactness of the scientific method. As Fr. Andrew Louth wrote in his excellent book Discerning the Mystery, “knowledge, truth, [is] now open to man: all he [has] to do, in any area of knowledge, was to apply the method.” Just as scientific hypotheses can only be verified by experimental data, historical truth is an objective reality that can be determined by studying hard facts. This approach even claims to be free of bias and the subjective nature of the human being.

Shouldn’t that be a good thing? An apologist of this approach to the Lives of the Saints, the Jesuit Bollandist Fr. Delehaye, puts it this way:

[Our] sole concern is to find out the true worth of the various records of the cultus of saints…to sketch the method for discriminating between materials that the historian can use and those that he should leave to poets and artists…and to put the readers on their guard against being led away by formulas and preconceived ideas.

Fr. Delehaye clearly prefers the historian to the poet. I find that very interesting, and will discuss this preference in a future post. He also sees the necessity of using the afore-mentioned scientific-historical method for the good of the Church, to prevent “false” elements in the Lives from harming the faithful. So far so good.

But how does this method actually work? As described by Fr. Andrew in Discerning the Mystery, this method has two presuppositions, without which the method will simply not work. The first is that objective historical truth can only be found if the historian is free of prejudices. His mind must be a blank slate, ready to accept as true whatever the facts tell him. The second presupposition is that truth is arrived at progressively, by a collection of hard facts that slowly “fill out” the body of knowledge. The problem is that the course of history is not as straightforward as science claims to be. Perhaps one can make an argument about the progress of science, but one would be hard pressed to define exactly what is the progress of history. One particularly seductive definition of such “historical progress” is to take the cultural assumptions of the present time as “more developed” than the attitudes of the past. Since “the writings of the past reveal a world which is different from ours, they show us a past which is remote from us. The remoteness strikes us as simply incredible.” (Fr. Andrew, again)

So one way to ensure that the Lives of the Saints are free from error would be to disregard the Church’s Tradition (or at least some part of it that can be conveniently disregarded by a demotion of capitalization) as a prejudice clouding the objectivity of the Church historian. That this is often done is undoubted; should it be done with the Lives of the Saints is a different question. But before approaching it, I should note that there are impressive voices among the non-Orthodox who have serious issues with this way of viewing history per se.

Hans-Georg Gadamer, a twentieth-century philosopher, compares the scientific approach to history to a conversation between two people in which one person doesn’t speak with the other at all; instead, observing him silently, constantly noting various behaviors, and making assumptions about him without actually engaging in a conversation. Gadamer insists that this sort of understanding is nothing but domination, and thus fundamentally flawed.

Gadamer’s preferred approach to historical knowledge can be compared to a conversation when two people are actually involved. Gadamer suggests this is the only real way of approaching truth: “I must allow the validity of the claim made by tradition, not simply in the acknowledging of the past in its otherness, but in such a way that it has something to say to me. This too calls for a fundamental kind of openness.”

The conversation analogy is extremely apt. After all, it was St. John of Damascus who made the revolutionary claim that the saints actually do not die! How can they die, if they continue to intercede for us in such obvious ways? They are not dead, but alive, and our interaction with them is the conversation between two living people, even if the only relationship we have with them is reading their Lives, as anachronistic as strange as they may seem to our all-too rational minds. The fact that elements of these Lives are included in the Church’s hymnography only further strengthens this point.

But this post is meant only as an introduction to this issue. Future posts will explore the use of the fantastic elements of the Lives in the hymns of the Church, the connection of the Lives with the Church’s theology of the icon, and an apology for the use of fantastical elements on their own terms, using arguments from a completely unexpected source – J.R.R. Tolkien’s incredible essay “On Fairy Stories”.

I am really happy to see you dealing with these issues. There are so many problems when we compare the 19-20th century historical approach to the traditional way of dealing with the past. It is imperative to notice that modern science cannot accept difference of quality between spaces or between moments in time, cannot weigh an ontological difference between the truth of the crucifixion and the truth that I put on grey socks this morning. For the scientific mind, one is no more true than the other. For a Christian, the crucifixion is more true, not because it is more factual, but because it is a “higher” event, one which makes the Logos more visible. And this qualitative difference is not in the “fact” but rather in how it is part of a story, a story which is bound with the human demiurge and the capacity to see/put meaning in chaos. And so the tropes, the patterns, the “mythology” is a part, not only a part but the very essence of the “story” without which we would only have a million billion factoids like an ocean of sand blown by the wind. And the “higher” these events are, the closer they are to the Logos, the more these patterns and tropes appear. It is not just true of saints stories, but also of the Bible itself which also has dragons and heroes and babies put on rivers in baskets. And one of the reasons historians cannot believe the miraculous and the beauty of narrative patterns is because their own spiritual life is made of sock color and 2 sugars in my coffee please.

Thank you for the wonderful comment! It’s inspiring me to consider adding a little more in a future post about a proper Christian vision of history, taking the Crucifixion as the starting point, something Fr. John Behr does very beautifully in a recent book of his. I already got some flack for using the word mythology, and I hope that people will read your post and more fully appreciate how a Christian view of truth varies so radically from the way even many Christians think, unfortunately.

I can understand why people don’t like the word “mythology”, but I think it can be used properly if explained, especially since many people today will use myth to discredit the Bible and Tradition. So since Sargon of Akkad is said to have been put on a river in a basket, then the story of Moses cannot be true since it obviously shares the same structure. Recapturing myth and the notion that the world actually unfolds and repeats those very patterns we see in stories, that the world is not, as historians would have us believe, a series of linear events connected to each other only “mechanically”. If I were to tell a historian that in the year 2013, the number of Christians who died for their faith doubled, and that at the beginning of 2014, when a boy dressed in blue and a girl dressed in red standing to the right and the left of the Pope of Rome let two doves fly away as a sign of peace, that those two doves were attacked by both a white and a black bird, the historian would tell me that it is a myth. And he would be right.

Dear in-XC Nicholas! An excellent article, and a topic I frequently have to explain by pointing out that biography and hagiography are two aspects of the same saint. They have differing missions, and it’s quite acceptable to work with both as long as we don’t get confused. I noticed the Cross Between the Antlers comments, and wanted to know if you were aware that the same legend is also repeated for Saint Hubert of the Ardennes? It is of course also the trademark of Jaegermeister, a German herb cordial, and recalls a tradition amon Germanic hunters, which I still had the privilege of participating in myself, of proffering your first kill to God by dipping your fingers into the wound and marking the sign of the Cross on the area between the antlers in blood. Anyway, may I have permission to republish this essay on our Antiquariat Hindrichs page on Facebook? Please look at it.

In anticipation of Great Lent

Vladimir

Dear Vladimir,

Thank you! Feel free to republish it, absolutely.

One of the best apologies I have read for the lives of saints is a quote attributed to Count de Maistre and is used as an introduction to “A Child’s Book of Saints” by William Canton (it is public domain and easily found online.)

“A saint, whose very name I have forgotten, had a vision, in which he saw Satan standing before the throne of God; and, listening, he heard the evil spirit say, ‘Why hast Thou condemned me, who have offended Thee but once, whilst Thou savest thousands of men who have offended Thee many times?” God answered him, ‘Hast thou once asked pardon of me?’

Behold the Christian mythology! It is the dramatic truth, which has its worth and effect independently of the literal truth, and which even gains nothing by being fact. What matter whether the saint had or had not heard the sublime words which I have just quoted! The great point is to know that pardon is refused only to him who does not ask it.”

Or to paraphrase a contemporary author, Neil Gaiman, “all the stories of the saints are true, some just didn’t happen.”