Similar Posts

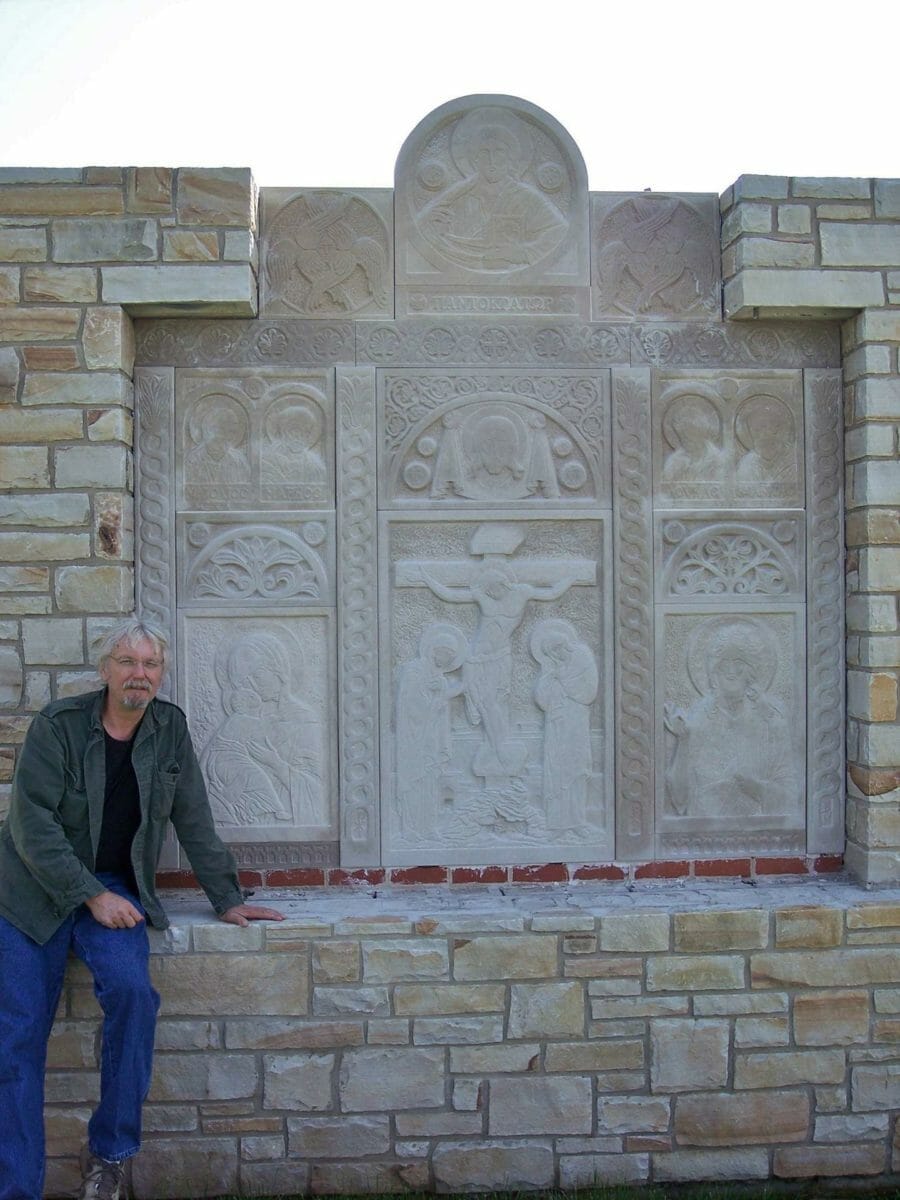

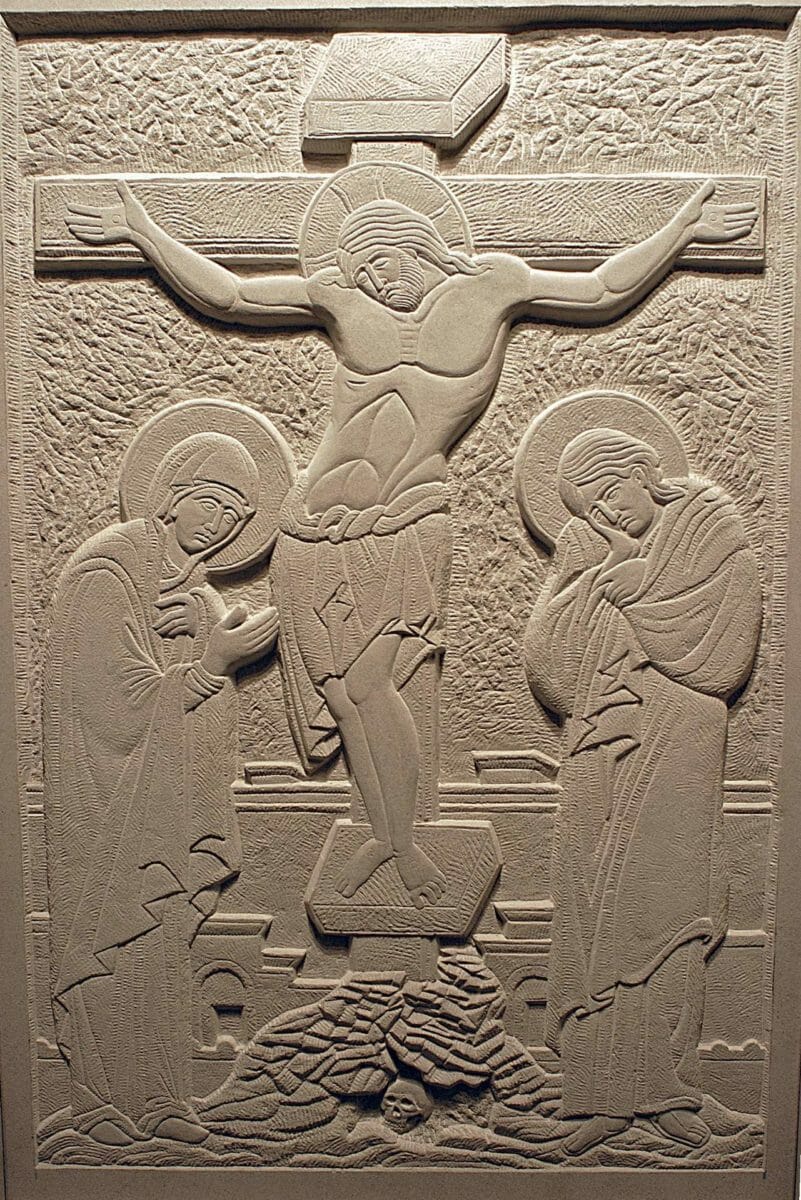

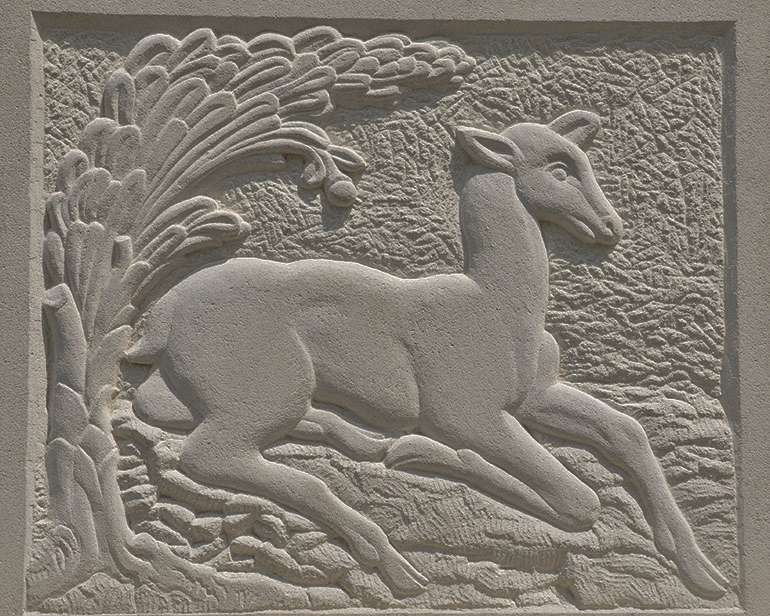

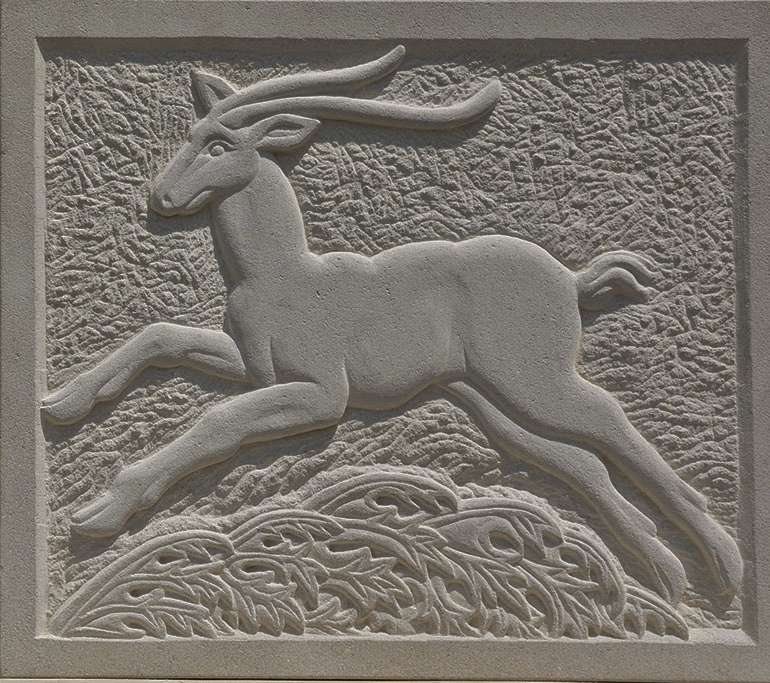

The following is an interview with sculptor Michael Lucas. Mr. Lucas is an accomplished artist who currently focuses on Byzantine-inspired carving in stone. Andrew Gould is working with Michael on an ongoing project to build a baptistery in South Carolina.

A. Gould: You started iconographic carving late in your life. Tell us about your background as an artist. Where were you trained, and what types of sculpture have you done over your career?

M. Lucas: I received both my BFA and MFA from the Pennsylvania State University. I attended two courses in sculpture as an undergrad, but neither concerned stone carving. Each was about modeling the figure in clay and then molding and casting the sculptures in plaster. While a graduate student (1979- 1981) I concentrated on drawing. In subsequent years I experimented with all kinds of drawing media and imagery. I was especially interested in recording the effects of light and shadow through pencil, charcoal and ink. I eventually developed a sustained approach with pen drawing, utilizing a refined cross-hatch technique. Most of the drawings dealt with a dream-like view of nature. This series was widely exhibited, in juried shows, and grouped in one-person shows. My success in exhibiting these drawings contributed to earning a tenured position at Penn State, which I still hold.

A. Gould: What began your interest in iconographic carving?

M. Lucas: I was raised in a family that was entirely Eastern European. My grandparents were all immigrants from the Carpathian regions of Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine. We were a mixed religious bag of Latin Catholics, Byzantine Catholics and Orthodox, a perfect reflection of our geographical roots. As it was, my parents belonged to a Ukrainian Catholic church near our home, and from early on, I was exposed to the mysterious world of icons. As a child I was almost haunted by them – their otherworldly faces and postures. They confronted me with their static stares and perfectly ordered clothes.

In the early seventies, the church had a fire that destroyed much of the interior, including the artwork. Sometime in the late 1980’s after graduate school, I was asked by the priest to try to paint some icons to help restore the church interior. Reluctantly, I began to paint compositions of feast days and such. The results were at first less than personally satisfying. I immediately realized that I needed to discover what icons were really about, their meaning as well as method. I accumulated a collection of books and images concerning icons – the theology and history of them. Eventually, I executed a number of iconographic murals for my church, which are still there. They were executed in oils on large wooden panels.

My father was a stone worker for a portion of his working life. When I was very young I would routinely see him splitting local sandstone with wedges, working it to building size blocks and finally squaring their faces and corners before laying them together with mortar. He would construct foundations and retaining walls. As I got older, I would help him move stone and hand mix mortar. Occasionally, we would even use his make shift forge to draw out and sharpen dull chisels and wedges. I was always fascinated with the beauty of stone. I was especially impressed when my father would level a stone for use as a step or sill. He would methodically chip at the top surface with a pointed chisel, carefully changing direction and weight of the blows to get an even, flat surface. I used to stare at the marks that the tool left and contemplate how long those beautiful tracks would last. I suppose that’s one of the main reasons that I insist on keeping point marks in the backgrounds of my own work.

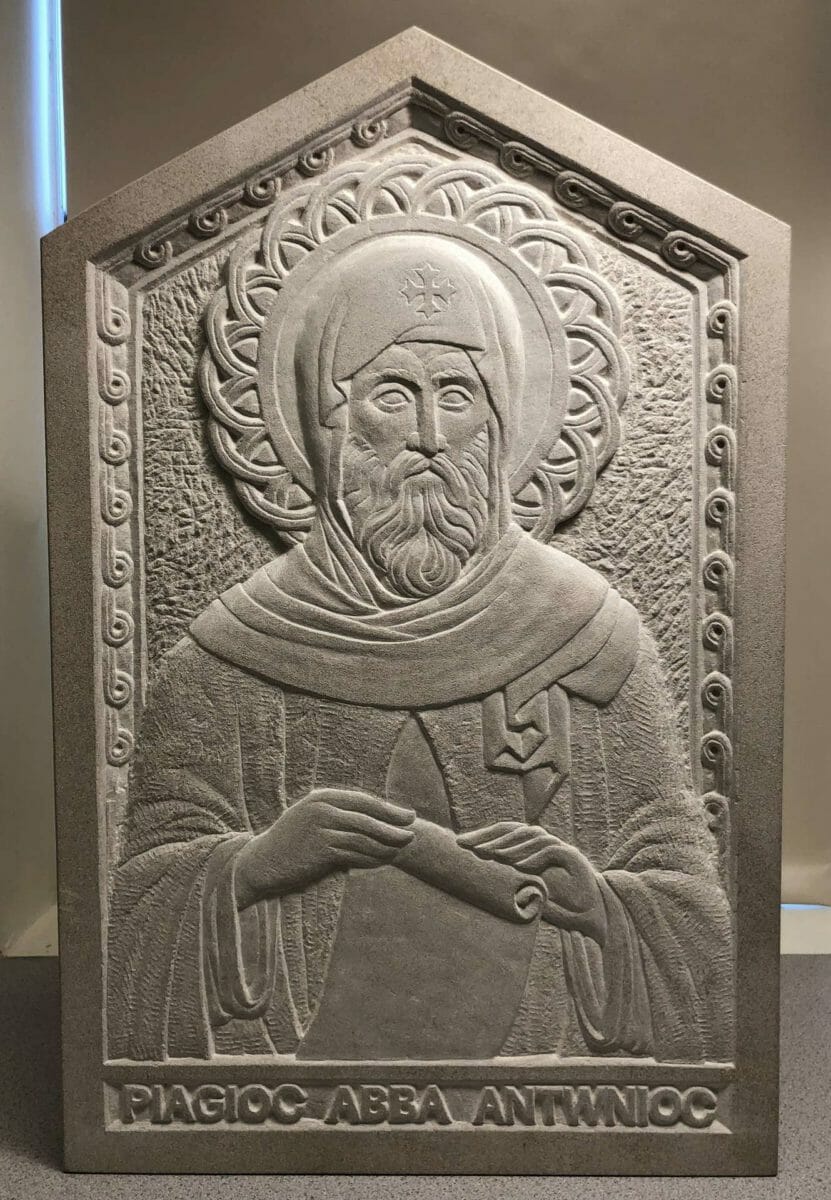

I am fairly new to stone carving. I began about 15 years ago, shortly after receiving tenure at the University. My first carvings were certainly experimental, being done on “scraps” of stone from a local stone supplier. As I gained enthusiasm, I bought many hand tools a built a shed in which to work. I began buying stone, cut to size, and piecing together a grouping of carvings that literally evolved as I made them. I was asked to show this grouping at the Antiochian Village in conjunction with an exhibit in their museum. The stones never came home and became a permanent outdoor monument at the Village. From then on I became a committed stone carver.

A. Gould: Is your interest in this type of work about artistic exploration, or out of a desire to serve the church? Of course, there is really no conflict between the two, but not everyone takes up liturgical art for the same reasons.

M. Lucas: There are three great interests that guide my artistic explorations. First, I am infatuated with history, especially the role of art in the history of civilization. Secondly, I want to learn more and more about Christianity: its beginnings, its early forms, the triumph of Orthodoxy and its living legacy. Finally, I am a believer in Old World craftsmanship and I wish to emulate that with my own hands and efforts. These interests are inseparable to me, and they combine in ways that give my life purpose and meaning.

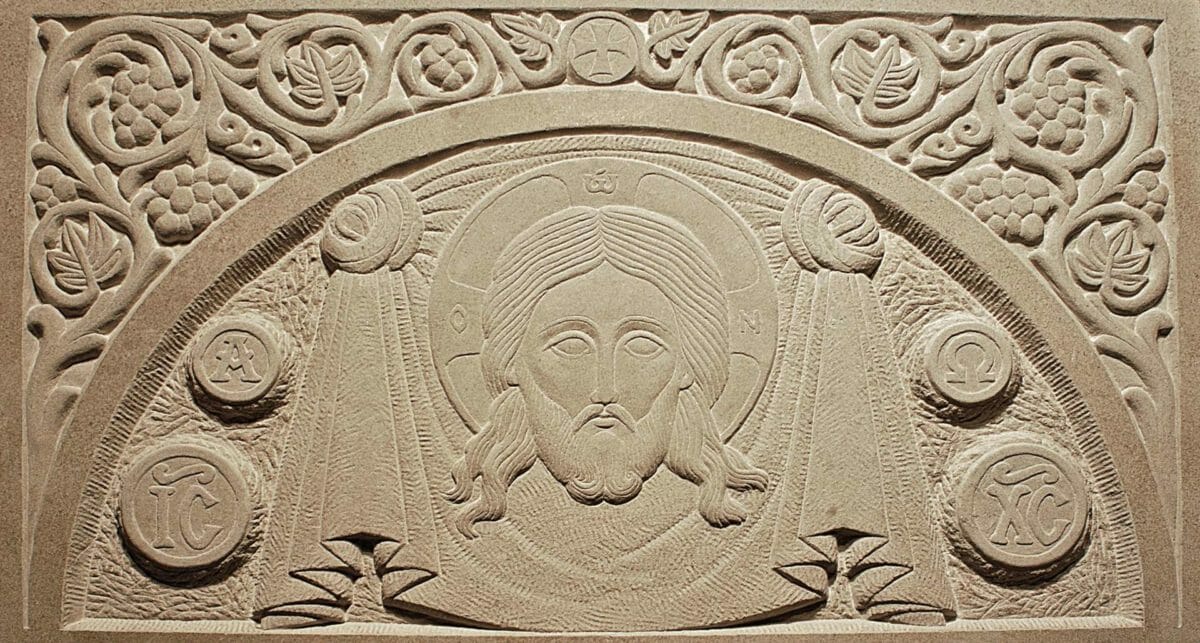

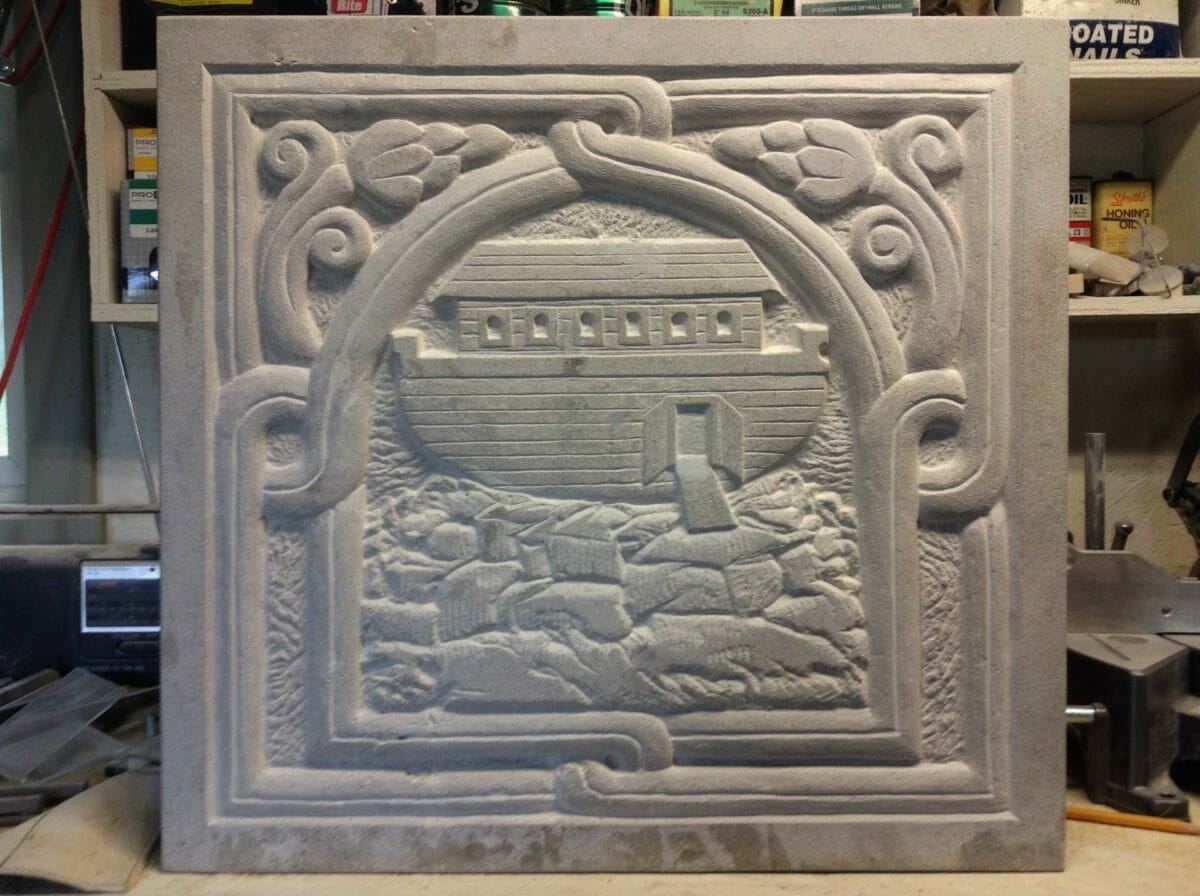

Panel for a baptistery, 2014. This is part of a large series of decorative panels carved by Michael Lucas for Saint John of the Ladder Orthodox Church in Greenville, SC. Andrew Gould is the project designer.

A. Gould: Though you carve Byzantine subject matter, your style of carving seems reminiscent of American sculpture of the early 20th-century. I see some resemblance to the heroic public sculpture of the Art Deco era, for instance. Am I correct in seeing this in your work? Tell us about your stylistic inspiration, and the sculptural tradition in which you see yourself fitting.

M. Lucas: I have always been attracted to relief sculpture. One of my infatuations with drawing involved the illusion of light and shadow. Values created with drawing instruments make one believe there is form where there is no form. Relief sculpture takes the illusion a step further – one creates real light and shadow through the creation of forms, especially planes at alternating angles. However, the whole effect is still somewhat of an illusion in that the relief is a semi-flattened version of 3-D reality. Some form is given; some held back, a concession between symbol and real, idea and object. I find this a fascinating concession and a representation of reality that is very much in keeping with theological concepts of the icon, namely an awareness that the whole effect of the image – no matter how well done – is but a representation, not the reality.

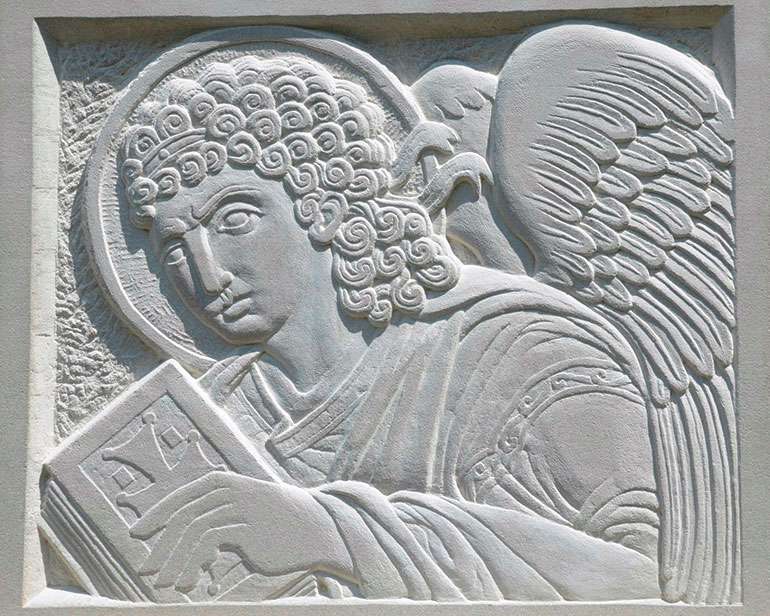

Beyond these visual and philosophical attractions is the notion that relief sculpture fits so well into the architecture of structures. I am inspired when I look at the relief embellishments of buildings from any culture or era, but particularly examples from medieval Europe and Byzantium.

I find it very interesting that you see an Art Deco flavor in my work. This is definitely not a conscience effort on my part. However, there are attributes in my carvings that may lend itself to this comparison. Of course, I will speak of Art Deco relief work. First, when I design a carving, I try to develop a balance in area between the positive forms and negative spaces, thereby already creating an interplay, if not a struggle, between the figure and ground. Secondly, I am always conscious of the perimeter of the piece, which I re-enforce with a border. I purposely try to make the forms approach and divert from this border, which further creates a struggle, as the forms are contained yet define the border. This attribute is the one that makes the work well suited for an architectural setting. Thirdly, I keep some forms large, less defined, perhaps more geometrical, and others small and more detailed. This may create a tension between an abstract, decorative quality, and realism. Finally, with regard to the border, I often make the border seem spatially ambiguous, that is, forms may seem to be behind the border, yet sit on the border in the same piece. I see some or all of these attributes in Art Deco carvings on American buildings.

A. Gould: What do you see as the artistic problems or opportunities that you need to focus on in iconographic carving? Many sculptors have difficulty achieving good iconic expression in faces. Expression is a hard thing in low relief. Others find difficulty in overcoming the dominance of painting as the normative expression of icons – that is to say, they have difficulty making it seem truly like sculpture, rather than an imitation of painting. What are your challenges?

M. Lucas: Perhaps the greatest practical problem that a carver faces is the need to create and preserve the major forms before creating detail. This is a concept that I discuss in all of my classes, whether sculpture, drawing, or painting. I have elevated this necessity to the axiom “go from the general toward the specific.” It’s a rudimentary principle, and one that my students get tired of hearing, but few follow. In essence, the sculptural quality of the whole is compromised by the attention (usually premature) to the constituent parts. The resulting effect is a flattening where all details exist in the same level. This can really contribute to the feeling of a painting instead of sculpture. Of course, not all carvings can be done in the same way and some are so small that this general rule must be compromised.

As to faces, well, what a vast subject this can be. I have spent my whole life drawing faces, I have literally hundreds of drawn portraits (from life) that I have done over the years. Yet carving one in low relief presents many challenges. The first challenge concerns the fact that the face protrudes far more than relief allows. If the face were to be carved in profile, how much easier the problem might be. But, of course, profiles are usually ignored in icons. The second challenge has to do with what you have termed expression. Expression is usually thought of in terms of a timely glance or a look that betrays a certain thought or emotion. The real problem with expression for the iconographer is the creation of a face that is at once timely and also timeless (or Divine-like if you will.) Therefore, momentary expression must, to a degree, be suppressed. This effect can be aided by formalizing the face via the stylization of features. Likewise, the very posture (position) of the head coupled with the hand gestures contribute to expression as desired in an icon.

When the icon works, there is an eternal expression. The image is simultaneously a representation of a particular saint and a Divine truth. It is idea as object, uncompromised by its need to be presented in recognizable time and space.

What are my particular challenges? All of the above and more. I am trying to better understand how multiple depths in the carving add to the sculptural quality of the work. I am trying to consciously create planes to play with light and shadow. I am especially trying to understand how faces must be pleasing to the eye anatomically, yet speak of far more than individual personality.

I am afraid it’s a bit early to notice myself fitting into any particular tradition. That awareness may or may not come, I don’t know. I am always wary of my work prematurely fitting into anything and it becoming less genuine. Maybe, in some final analysis, my little contribution will be to outsider art. That’s okay too.

A. Gould: How do you see your career evolving after your retirement from teaching?

M. Lucas: I have been teaching at Penn State’s Altoona College for a good many years. It’s been a wonderful career on very many levels, but I am looking forward to retiring in a year or so. Certainly, I am most looking forward to devoting more time to carving and developing my experience with icons and the Byzantine style. I have slowly built a studio for this purpose and look forward to spending much time in its semi-secluded setting. I would love to acquire an occasional commission.

A. Gould: Is there any special project or major work that you would like to accomplish in the coming years?

M. Lucas: For my own personal pleasure, I am slowly enhancing my studio with stone casing and limestone carvings, mortared together. I want it to become a little work of art in itself, but that is always there, and has to do with a personal sense of place. My dream though, is to have a major commission – perhaps the carving of a whole iconostasis, or a large outdoor shrine, who knows? But, like many artists, the dream has to do with creating one big unified whole- a project that pulls it all together.

A. Gould: Thank you, Michael, for sharing your work with us.

Michael Lucas can be contacted by email at: mrl12@psu.edu

Wonderful interview. His work is brilliant–strong, nuanced, but in the great Iconic Tradition. He and Jonathan Pageau, another carver, inspire me. Kudos to Mr. Lucas for his beautiful stone carvings!!!