Similar Posts

The appearance of Kurt Sander’s Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, which was released simultaneously on April 26, 2019, in recorded form by Reference Recordings and in print form by Musica Russica, in many ways represents a unique and unprecedented event in the realm of Orthodox liturgical singing in North America.

The work was created in response to a commission from PaTRAM—the Patriarch Tikhon Russian-American Music Institute—something unheard of in Orthodox liturgical music today, whereby a composer is given the opportunity to exercise his or her creative art on a high artistic level and is rewarded for it monetarily. Iconographers, architects, and other liturgical artists receive commissions all the time. As far as this writer knows, this is the first instance of an American Orthodox composer being tasked with creating a work of liturgical music in the English language. The results are nothing short of breathtaking!

Attempts to describe music in words can never successfully convey what ultimately can only be expressed by musical sounds. Nonetheless, Kurt Sander’s new Divine Liturgy is a musical phenomenon that merits being written about if for no other reason than to entice you, as the reader of this review, to drop whatever you are doing and immediately purchase the CD or access it online. In doing so, you will open a window through which the beauty of the Heavenly Kingdom will shine into your life in a particularly intense and radiant fashion.

From the very opening exclamation, “Blessed is the Kingdom…,” and the choral “Amen” that follows, it is apparent that this is an extraordinary recording—the realization of an inspired artistic vision by PaTRAM co-founders Alexis and Katherine Lukianov, together with conductor Peter Jermihov, to give this newly commissioned work an appropriate premiere presentation. The PaTRAM Institute Singers, 25 voices strong, bring together an outstanding array of vocal talent, reinstituting the high standard of professionalism that in former times had gone hand-in-hand with the performance of the great Russian Orthodox liturgical choral masterpieces. Jermihov, a well known conductor of Russian-American background and a champion of living composers in the Orthodox Church, proves to be a perceptive and sensitive first interpreter of Kurt Sander’s work, exercising tasteful artistic control over every minute liturgical and musical detail.

The artistic vision of both the composer and the conductor entailed a complete presentation of the Divine Liturgy, with all the clerical exclamations and litanies—reaffirming that the Liturgy is a continuous and uninterrupted musical phenomenon, which leads the listener/worshiper inexorably to the climactic moment of the Holy Eucharist. The extraordinary vocal prowess of Protodeacon Vadim Gan; basso profundo Glenn Miller and baritone Keven Keys, who seamlessly execute the litanies and exclamations; along with tenor Daniel Shirley and baritone Evan Bravos, whose solos model the role of chanter-canonarch, highlights the traditional Orthodox artistic principle that everything in the Divine Service should be on the level of excellence that is “fit for the King.”

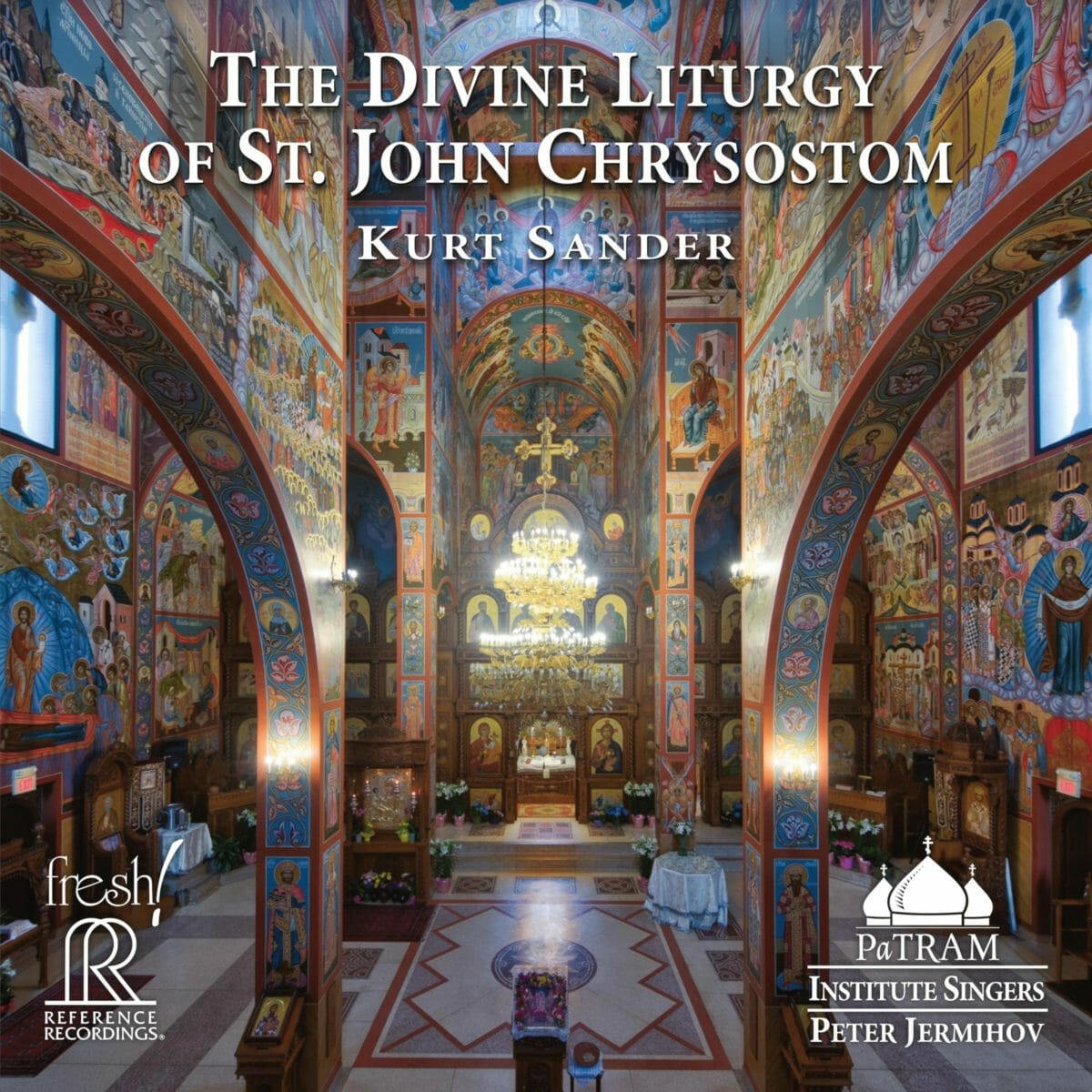

In the resonant acoustics of the New Gračanica Church[i] the PaTRAM Institute Singers sing with a sound that is best described as “brightly glistening and shining,” whereas at other times their timbre assumes a warm sonorous glow. It is clear that the singers are resonating mentally and emotionally with the texts and “liturgical moments” they have been tasked with communicating. The copious dynamic and expressive markings in the musical score, never arbitrary but always purposeful, are executed faithfully and with understanding. This glorious array of sound, as dazzling as the frescoes on the walls of the New Gračanica Church, has been masterfully recorded, engineered, and reproduced by the award-winning team from Sound Mirror, led by multiple Grammy Award winner, Blanton Alspaugh.

A classically trained composer, Kurt Sander converted to the Orthodox Faith over 25 years ago. Since that time, he has immersed himself in both the analytic study of Orthodox sacred music and composing works either directly based on Orthodox service texts or otherwise inspired by Orthodox themes. “I am committed to looking at Orthodox choral music as a living creative tradition,” he states in the preface to his Liturgy. “Every Orthodox Christian artist has an obligation to nurture creativity, as it remains one of the most essential and immediate ways we have to glorify God. It is through this process that we understand God as someone to be worshiped, not simply as a theological concept that we convey in paint or through song, but as a Father to be loved and glorified.”

Such an understanding of the Orthodox creative artist’s role places Kurt Sander solidly within the tradition of the Church, and this posture is clearly reflected in his liturgical music. As a gifted practitioner of the composer’s craft, as well as a music scholar (he has taught music theory and composition at Northern Kentucky State University for a number of years), he displays great skill in writing music with sonorous connections to many of the great Orthodox choral composers who came before—from Rachmaninoff, Gretchaninoff, and Steinberg, to Sviridov, Trubachov, Moody, and Pärt. As a modern-day American composer working in academia, he also demonstrates a stylistic awareness of prominent contemporary composers of sacred music outside the Orthodox tradition, such as Morten Lauridsen and René Clausen, to name a few. Consequently, while Sander’s compositional voice remains recognizably his own, the sound of his Liturgy is unmistakably “American” and at the same time unequivocally Orthodox and universal. One could easily apply the terms used to describe the sacred works of Russian composer Alexander Kastalsky more than a century ago to Sander’s work as well: “…quite unlike the flamboyant creations of a single individual, they rather resemble a composition by an entire people,… coming into this world on their own accord, seemingly without the will and effort on the composer’s part.”[ii]

Sander does not succumb to the seeming need of many present-day composers to delve into the sphere of dissonance and atonality, the hallmarks of “post-modernism.” He has clearly embraced the fundamental underlying aesthetic of Orthodox liturgical music—to reflect and embody, as much as humanly possible, the beauty and splendor of heavenly worship—the eternal Liturgy that takes place around the Throne of God, as described in the Book of Revelation (ch. 4 and 5). And although such things lie within the realm that “no ear has ever heard” (to use St Paul’s expression in 1 Corinthians), listening to great works of sacred music composed through the centuries, one senses that God nonetheless reveals glimpses of heavenly sounds to creative artists who love Him and seek Him with their whole heart.

It took Kurt Sander more than one year to compose the Divine Liturgy, and there were struggles and challenges along the way. “Setting the text of the Liturgy is not like setting other sacred texts. One must consider larger issues of unity and the preservation of an underlying liturgical narrative,” Sander explains. “After several fruitless starts, I eventually found my musical inspiration in the opening of the Third Antiphon, which recalls the words of the repentant thief: ‘In Thy Kingdom remember us, O Lord, when Thou comest in Thy kingdom.’” From there the composer set out along a path less traveled: “I abandoned the natural inclination of a composer to set first the more significant parts of the Liturgy like the Cherubic Hymn or the Anaphora. Instead, I turned my initial efforts to the little elements of the Liturgy—the litanies, responses, the one-sentence choral utterances, etc. In so doing, I came to the realization that these are actually the fibers that hold the work together.”

The result is truly unprecedented. Whereas previous settings of the Divine Liturgy and other liturgical cycles (Vigil, Passion Week, etc.) essentially consist of a number of thematically unrelated sections or “movements,” Sander’s Liturgy is the first Orthodox choral work to exhibit a thematic unity from start to finish—at times subtle, at other times, more pronounced—achieved through the techniques of leitmotif and thematic transformation. Individual sections stand on their own musical merits to be sure, but in listening to the entire work from start to finish one experiences a harmonious, well-balanced whole, like beholding a large, multi-tiered iconostasis—all executed in the same style—that has been set perfectly into its supporting carved framework and placed proportionately within an appropriate architectural space.

Orthodox sacred singing has always strived to achieve a perfect marriage of the text and the music. This marriage occurs on at least two levels—the physical, which has to do with the structural ways in which the melody gives voice to the words; and the spiritual—how the full expressive means of the music are employed to embody and call forth the logikē latreia, the “rational worship” within the hearer’s innermost being. To be successful in the latter, the composer must not only enter into and comprehend the text with his intellect, but must love the text and what it is saying with his heart. In the music of Kurt Sander’s Divine Liturgy the love is obvious—love for the Persons of the Holy Trinity, the Mother of God, and for the people of God—those to whom and on behalf of whom the hymns, prayers, and responses are sung. The composer’s intent is reflected in some of the unusual expressive directions in the musical score, some in Italian: Con molto calore (with great warmth), Delicato (delicately), Jubiloso (with jubilation), and elsewhere, in straightforward English: With contrition, Peacefully, Meditatively, and With humility. When properly interpreted by the performing ensemble—in this instance, Sander was directly involved in the recording as a singer—the composer’s love is communicated unequivocally to the listener.

Both the score and the recording of Kurt Sander’s Divine Liturgy represent an unprecedented phenomenon on the artistic landscape of Orthodoxy in America. They are, simultaneously, “a new word” and “the same word,” which will undoubtedly resonate throughout the North American continent and Anglophone Orthodoxy (and beyond[iii]) for a long time. In the wake of what is in many ways a pioneering achievement, we can look forward to the creation of other large-scale American Orthodox liturgical works, further recordings on a professional level of excellence, as well as, we may hope, new works by Kurt Sander accessible to church choirs of varying sizes and levels of ability. The present work and its premiere recording show just how high the bar can be in Orthodox America.

~ ~ ~

The recording of Kurt Sander’s Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom is available from Reference Recordings both as a physical CD and in a variety of downloadable formats. Sample tracks can also be heard at this link:

https://referencerecordings.com/recording/the-divine-liturgy-of-st-john-chrysostom/

The musical score is available from Musica Russica: http://www.musicarussica.com/collections/sa-dl

[i] The Divine Liturgy was recorded on August 3-5, 2017, at the New Gračanica Serbian Orthodox Monastery in Third Lake, Illinois. The liturgical premiere took place several weeks later, on September 12, 2017, the altar feast of St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, in Howell, New Jersey, presided over by His Eminence Metropolitan Hilarion of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR).

[ii] Ivan Lipaev, [Concert review], Russkaia muzykal’naia gazeta 4 (1898):400, cited in V. Morosan, Choral Performance in Pre-Revolutionary Russia, Musica Russica, 1986, p. 221.

[iii] In January 2019, Sander’s Liturgy, adapted into Church Slavonic, was premiered at the Moscow Conservatory in Russia, under Peter Jermihov’s direction. One may safely call this a totally unprecedented occurrence and a remarkable reversal of the path by which much of the Orthodox choral repertoire has traveled to churches in the New World.

Thank you, Vlad, for a fantastic account of a wonderful achievement. As one of the singers on the recording, I can say you’ve captured the spirit and beauty of the piece, and I’m thrilled to see Kurt and Peter getting their due. Glory to God!

Can you unpack this a bit? “As far as this writer knows, this is the first instance of an American Orthodox composer being tasked with creating a work of liturgical music in the English language.” No question that the idea of paying composers is important – thank you for emphasizing that! I hope people will listen. At the same time, this isn’t the first paid commission I’m aware of. Did you mean something more specific?

Thank you again, Vlad – I hope this work sees every success!

Listening to the Beatitudes selection definitely makes me want to buy and listen to the whole recording. Sander has the depth of many years of study and immersion in choral literature, especially on the Russian side, to support this offering from his heart to the Church.

I’d also be interested in listening and comparing the English version and the Slavonic translation. I can imagine the Slavonic “fitting” the music in a way that I don’t think Greek (and some other languages as well) could manage. Listening to the Beatitudes I’m hearing exactly what I was trying to get across to you a few months ago, Richard. Though the music can “fit” with another language and convey beauty, love and prayer, this is a work that was created to “fit” English primarily, and it fits it wonderfully well. It does indeed have an American sound.

Our choirmaster, Nicolas Custer, composed a Divine Liturgy in honor of St Katherine. It was commissioned by one of our sopranos – named Catherine – in thanksgiving for her recovery from a serious heart condition. It uses some tone 5 material from a Cherubic Hymn, I believe, and carries that theme through each section, though the sections can also stand on their own. It actually reminds me of colonial Mexican Baroque church music I’ve heard, though not overtly – simply the “aroma” of it is there. Our choir very much enjoys singing that and his other works; we’re privileged to have our own composer in residence, and I wish other parishes had that opportunity.

Dana

Kurt is very much steeped in the Slavic choral idiom, so it’s not entirely surprising that his English choral music would sound like it could accommodate Slavonic and not Greek.

Your “fittingness” comment is a bit confusing, however; are you saying that music that sounds like it could “fit” Slavonic sounds more “American”? And the trouble with saying that it “has an American sound” is, well, it might, but which “American sound” do you mean?

I had occasion to read this article today: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/05/20/rhiannon-giddens-and-what-folk-music-means

There was a bit that jumped out at me. Food for thought, perhaps:

—

In the book [“Origins of the Popular Style“], [Peter] Van der Merwe attempts to address why the popular music of the twentieth century sounds the way it does. He notes that many different folk-music traditions tend to contain a particular kind of melody or set of notes, “neutral intervals,” between major and minor. In America, we call them “blue notes”—flatted thirds and sevenths and fifths. They can suggest moaning and dissonance. The cord that binds the various global sub-styles of folk in which these notes occur is what the ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax termed the “Old High Culture” of Eurasia, which stretched back to Mesopotamia. Strangely, perhaps, given that we are talking about twentieth-century popular music, it was often Islamic song traditions that acted as the conveyor for these deep strains in world music. Van der Merwe shows how the “gliding chromaticism” characteristic of the blues spread via Islamic influence into West Africa (in particular the Senegambia region) and, via Spain, into Ireland and the “Celtic fringe.” From those places, these styles and sounds rode farther west, to North America, on slave ships and immigrant ships. In the American South, the Celtic and the African musical traditions met. It was an odd family reunion. Each culture had its own songs, but the idioms understood one another. The result was American music.

Congratulations Kurt !! I want to hear your work !!! Proud of you. — E. Hisey

Richard, I suspect Dr Morosan means is that there very few complete musical settings of the divine liturgy designed specifically for English (ie most are set in another language such as Slavonic and adapted to English). The only other ones I’m aware of our John Boyer Byzantine-ish setting for Cappella Romana and an Ukr. Catholic one (Hurko?). As you mentioned there are hundreds individual hymns or sections that have been composed.

Kurts work is great though!

I think actually looking it up that there is a few in the Byzantine Catholic sphere (Sembrat, Sfianchuk)