Similar Posts

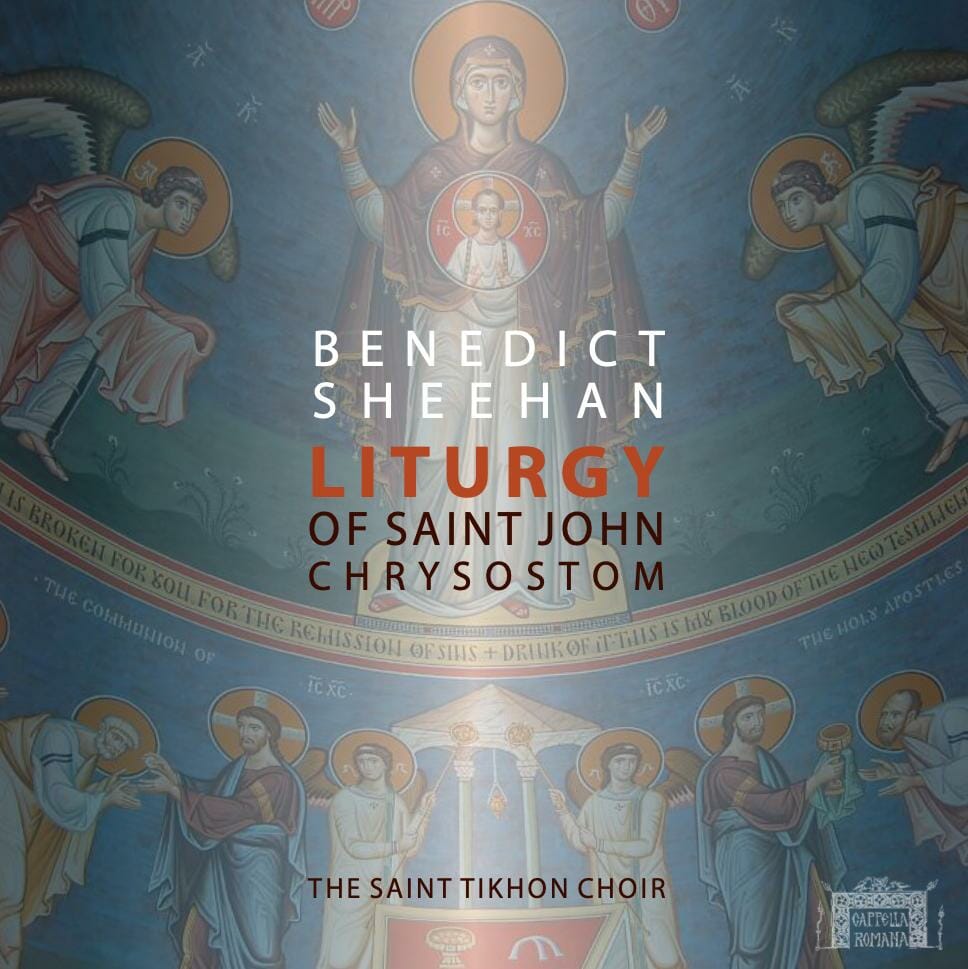

An Interview with Benedict Sheehan on the Premiere Recording of his Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom

This week Cappella Records released the world premiere recording of Benedict Sheehan’s Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom. It’s an ambitious and truly incredible setting, full of sweeping melodies and rich deep harmonies. It calls to mind the great concert liturgies and masses by famous composers of the past, and can compare admirably with any of them. The recording itself is sumptuously beautiful, with the crisp clear audio needed for the wide vocal range and complex harmonies. If given the choice, definitely purchase the CD+Blu-ray package to take full advantage of that.

I had the opportunity to interview Benedict about this project the week before the release, and the following is a transcription of my video interview:

H. Provonsha: You’ve composed an entire setting of the Divine Liturgy in the tradition of the great Russian composers – the likes of Tchaikovsky or Bortniansky. What brought this about?

B. Sheehan: So the origin of this particular piece was a commission of the PaTRAM Institute. They approached me in 2015 with a commission saying, “We want you to write a complete setting of the liturgy,” and the assumption from the beginning was that it would be recorded by their ensemble. I believe, not long before they talked to me, there was already a commission in the works from Kurt Sander, so they did these two commissions basically at the same time, or not too far apart. They recorded Kurt’s project sometime in 2017, I think, and I completed my score sometime in June 2018. For a whole range of reasons, it didn’t work out for PaTRAM to record it, so I proposed that I actually record it and organize it myself. So they contributed some additional funding for the premiere performance, but I funded and organized the recording on my own. That was the impetus of the piece.

The terms of the commission were that I compose the liturgy in the Russian style and also to include a lot of low notes. It has some of the largest number of low bass notes of any piece I know. There’s actually a low E (E1).

What a thing to be able to hire a basso profundo!

For the recording I actually had four.

You mentioned that it was composed in the Russian style, but were there other influences as well?

They asked me to write the Liturgy in the Russian style. I’ve spent basically my entire musical career steeped in that tradition, to one extent or another – although, primarily, in that style as it exists in English and in America. So I am possibly unique in being a composer who’s composing large scale works that are, in a sense, coming out of the English-language Russian-Orthodox tradition. So already I’m coming at this not being Russian, not feeling like I need to be or am trying to be, but at the same time, I’m aware of that style of music. It’s in my ear, it’s in my consciousness, and it comes out in the way I write for choir – especially when I’m not really thinking about it.

So I decided pretty early on that although I was going to write out of my experience of this music, I didn’t want to repeat music that’s already been done. I’m acutely aware of the ways in which language generates musical sound and rhythmic shapes; things like phrasal dynamics and accents. All those things are very different between Church Slavonic and English. So in order for our church music in the Orthodox Church to be in the Russian style but in English, in a sense both of these things have to evolve. Both the music has to evolve, and the things that are natural to English need to evolve. When they come together, they create a new phenomenon. Regarding singing music in English, if you look at the American English tradition of singing, you’re largely dealing with all metered music and metered texts – music that falls neatly into two, four, and eight bar phrases. But that is not quite the way Russian chant operates, so to me that was an interesting point of musical conflict. So let’s create something that is a mingling of these two worlds. It’s this idea of dealing with phrasing, with the way accents occur, the way text is set to music. I think the end result with my piece is neither purely American nor purely Russian in style, and that was my goal.

Now, I have a real love for a broad range of music (every musician does). I particularly love the sound of some of the early American psalm singing – things like the Sacred Harp and Southern Harmony. So that sound is in my ear as a kind of music that’s kind of interestingly… it sounds American to my ears, although I wouldn’t say that it’s the definition of American music. We have so many different cultural influences in America that you can’t really point to any one thing and say that it’s American. You might as well say African American spirituals are American music, or jazz is American music, or, I don’t know, German drinking songs or Indian ragas are American; all these things come together. So what’s really American is a bunch of different things coming together and having to work together. So the effort was to find commonalities between these and martial them into a common aim in worship. That to me is very American. In that sense, the Russian music that we sing in church right now is in the process of becoming American. So I was coming at it with that idea, too.

Basically I gave myself permission to draw in a whole range of different sounds that fit into a musical aesthetic that still sounds like church – as though I would want church to sound like that.

I noticed you have eight voices in some movements, which, as a choir director, I would love to attempt, but our choir is too small.

There’s a lot of big textures. I knew what PaTRAM was after in terms of what they wanted to perform and record, and I knew it would be a choir or 35 (in the contract) professional singers, so I wrote for that kind of an instrument.

When listening to this with the score (thank you for that, by the way), I noticed some elements that reminded me of Vaughan Williams and Arvo Pärt. Was I imagining that?

No, I think of a composer as a filter, and all of those sounds are in my ear and I love them, so depending on what I think is demanded by the music or demanded by the text, different things are going to come out. There certain parts in there that I think sounds like Arvo Pärt or sounds like Vaughan Williams. I think the connection to Vaughan Williams is interesting because he came at a lot of his music as a lover of folk melodies and chant melodies, and basically arranged them, or wrote music inspired by them. My creative process in writing this was similar, in that for a number of movements I composed a melody that I thought was kind of like a chant, and then I arranged it. In a way, these are kind of like chant arrangements; it’s just that I composed the chant also.

How do you see this affecting the future of Divine Liturgy compositions?

I like that you asked it that way. I’ve gotten this question a few times: “What is the point of this? Nobody’s going to be able to sing this in church,” to which I would have a different answer. To your question, that’s a thing that I’m very interested in. There’s a metaphor that I’ve used a few times. I was dealing with a church at one point that was working on their music program, and they were debating about how to fundraise and what their goals were (I think I originally got this idea from Metropolitan Tikhon, now that I say this). The church wanted to work on building up their music program, but had this big obstacle. They had a huge capital campaign going to repair their roof, and they thought this might conflict with their music campaign. The question I asked them was:

“Why do you have a roof to begin with?”

“So our church won’t leak.”

“Well then why do you have a church?”

“Well, so we can have Liturgy.”

“So why wouldn’t you invest in the Liturgy?”

We have this mindset that, somehow all this work we’re doing in music and the arts and the liturgy is somehow stuff you get to after you deal with the more immediate practical issues of making a handicapped entrance, or fixing the roof, or fixing the air-conditioning, but it doesn’t deal with why we have a church to begin with. There will always be things to repair on your church, but repairing those things won’t tell you why you have a church. That I see as a metaphor — I’ve spent the best part of the last twenty-five years either arranging, composing, transcribing, or editing music that can be used tomorrow, by the six people that we’ve got in our choir, or that has only two parts, or that doesn’t have a tenor, because we don’t have a tenor. I know how to fix these problems and how to supply the immediate needs. The problem is that, if that’s all we do, at some point, we’re not going to remember why we sing in church; we’re not going to remember what that music is for or why we should care about it. So my goal with writing a piece like this is to say, “We can solve all these practical problems, but we also need to be inspired. We also need something to reach for, and we need to have an experience of a thing we didn’t even know could be done. So if there’s going to be American Orthodox music at some point, we have to have things they’re inspired by. I want it to remind me of that, or sound like that.” A lot of the music we do sing in church is arranged-down versions of other things, or not even arranged down. The reason four-part music spread everywhere is because, at some point, there were examples of four-part music that just blew everyone away, and we said, “This is the best thing I’ve ever heard; I want to do that.” So they might do twenty percent of that, but in a sense they’re still on the same continuum; they still have a thing they’re trying to reach for. So you need Bortniansky’s concertos to have L’vov’s Obikhod tones. In order to make telephones work better, we had to land on the moon. That’s actually literally true. The Corning Glass company, in their efforts to make a stable and temperature-resistant exterior coating for the moon lander, invented fiber optics.

So you write a very complicated, but a very elaborate, beautiful piece of music to say, “This is what can be done if you have a huge cathedral choir, or a professional concert choir,” but you can draw from elements of that to make smaller, less-complicated parish settings.

Absolutely. Or somebody else with that sound in their ear will then translate that kind of a sound or adapt certain elements of it, and will make music that will fits their immediate needs. But if we only write music to fit immediate needs, we’re going to run out of steam. We already are running out of steam.

Do you foresee an effort to compose a new Octoechos for the English-speaking church?

I think tradition is a context. Tradition is a jig, meaning it’s a set of norms that get set up over time, based on common solutions to common problems, and common triumphs in achieving common goals. Over time, this thing we call tradition begins to arise. I like to think of them as jigs. I’m stealing the idea from the writer Matthew Crawford, who wrote Shop Class as Soul Craft. It means that you don’t have to decide everything all the time. It means that all kinds of things are already decided for you, but anyone who works with a jig knows that you have to check your jig all the time for accuracy, and you also certainly understand that a jig only works for certain tasks. If a new task or new materials come along, then you have to either update your jig or create a new one. It’s not like you don’t have a jig at all or you forget everything that you knew before and create ex nihilo – that’s not how a tradition works. The way we sing the tones is a jig, or a number of jigs. They’re a pretty effective jig for a certain set of goals, and for a certain set of materials, and for a certain context, but I wouldn’t simply say that we need a new Octoechos. What I would say is that it’s time for us right now to look at our jig and ask whether it’s still working, and if it isn’t, then why not and what can we do to update it and improve it and make it work again. That is a job I think needs to be done. And it doesn’t only need to be done for the eight tones, but for the way we sing in church generally. I think the very fact that people are asking this question often — why are we doing this? (because it’s not obvious why we keep singing the eight tones the way we do) — the fact that more and more of us are not sure why it is the way it is – that’s a pretty good indicator that it needs to be updated. But in order to update the jig, you don’t just throw out your old ones, because you need to know how to make a jig. Maybe only some of it needs to be altered, or maybe we need some entirely new jigs, but it’s not a thing you’re creating ex nihilo; it’s a thing coming out of what you know.

For instance, I’ve heard some people say that we need to excise Russian music from American parishes and replace it with all American music, and to me that’s painfully ignorant. How would you do that? What even is American music? That’s not how a tradition works. All these things evolve gradually over time. I would say I would love to see a time, or maybe for my grandchildren to see a time, where you could point to there being such a thing as American chant (if that’s even a real thing; I don’t know). I would love to see a large body of new music composed for us right now. All of that will necessarily be informed by what we’re doing in churches right now. If we just try to, in the abstract, try to replace our chant with something completely different, it just won’t work. The overarching criterion for any context is that it needs to sound like church to the people that go to church. That may sound like mere relativism, but it’s not; there are commonalities to all of the things that have sounded like church music in the past and that do sound like church to us now. Those things are very hard to define in the abstract. I think that they’re still real, and if we allow ourselves to be informed by that, then we’ll do good work. There’s all kinds of music that’s been done in the church that we’ve forgotten about, because it didn’t work.

In your setting of the Divine Liturgy, were there any direct quotes from ancient chant?

Oh yeah. A lot of the ways that I write melodies for church generally are informed by chant. All of those kinds of motifs are in my ear, and I’m aware of them both consciously and unconsciously. In a sense, all of it is informed by chant, but the Alleluia is straight out of Znamenny chant. I arranged it, I added a lead-in in the alto, and took out two motifs from the original that didn’t fit with what I wanted to do. Then the communion hymn Praise the Lord, is taken from a Valaam chant that I know as being set to Receive the Body of Christ, so it’s not actually a melody for that text, but I thought it sounds even more like a communion hymn. I altered the melody a bit, turned it into this double-chorus texture, added a countertenor soloist, and went to town. Those are the two obvious examples, but if you go through my writing (maybe this would be a fun doctoral project for somebody after I’m dead), I would contend that you could probably find chant analogues in almost every phrase and motif.

Is there some relationship between major and minor in Orthodox music?

I would say if you look at chant, minor modes tend to be more common than major modes. I wouldn’t say there’s a one-to-one correlation with an emotional quality. I don’t even think that exists in Western music. Of course you can say, “This is sad and tragic, because it’s in a minor key; this is happy and triumphal; it’s in a major key,” but in the Orthodox tradition, what would be the most joyful piece of music of the entire church year? You’d think it would, of course, be the Paschal Troparion, but in almost every chant it’s in a minor mode.

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced while getting this project completed?

The way the schedule worked out, I had singers that had to leave by a certain time, and the production company had to come straight from another project in Boston, then had to go straight to another project in Atlanta. We had a really narrow window in which to record, so we actually did this in ten hours, which is about 60% of the time you would normally expect for this amount of music. That was one of the biggest challenges; to work efficiently. They did such an amazing job! We budgeted for twelve hours, but we finished in ten.

The recording quality sounds amazing!

The singers we hired are some of the best in the business, and the production company is also the best in the business, and together they did a fabulous job.

I would say about 50% of the choir are people who are members of the Orthodox church, so one of the interesting things I have to do is introduce the singers who are not Orthodox to the sound that I’m trying to get, and to the things that are inherently part of the ethos of the Liturgy. One of the biggest challenges was to convey that. One might say that you have to be Orthodox and go to Orthodox services, and I understand that. But I have to view this as a creative challenge. Can you actually break it down and do a task analysis? I would argue that you can. If you’re organized and you put enough thought in, you can actually just explain to people what it is that makes it sound “churchly”, and if they’re good musicians, they’ll do it. So that was my experience, but I had to put some thought into it to achieve that.

What exactly is the sound that you’re going for?

I would almost say that there are very few successful choirs right now singing with uncontrolled vibrato; that’s kind of a thing of the past. I would say that I allow the singers to use a more natural vibrato more so than other conductors. There’s a difference between vibrato and uncontrolled vibrato; the latter is just bad singing. A lot of people like to point to an “operatic” style of singing – that’s the word people like to use. It comes from choirs that just weren’t as good.

I actually believe that, in general, choirs are better than they ever have been, and that’s true all over the world. I think there’s been a rising standard of choral music over the last twenty (maybe forty) years, starting with people like Robert Shaw, and may even going back before him. I think that the early music movement, with some of those pioneering groups like the Tallis Scholars and the Academy of Ancient Music, has had a lasting impact on what people expect from a choral recording.

You don’t usually have to explain to people, “Keep your vibrato under control so that you can sing in tune.” If you’re a good singer, you don’t need that explained. The biggest thing that I have to tell people is, “Don’t make every moment an event.” Basically, it’s a kind of expressive simplicity. By that I don’t mean it’s lacking anything; I mean that it’s waiting for a thing. If you make every moment sweet, then by the end of it, it’s going to be too sweet. It’s like a dessert. The French rule for desserts is “if it tastes sweet on the first bite, it’s too sweet on the last bite.” So the first thing you taste (in this context) ought not to be sweet, but be some other taste. Choral music right now is kind of music that’s very sweet. What I tell singers is, “Don’t be expressive for a while. Let this build; let the expectation build.” In a sense, if you restrain that and put your energy instead into focusing on your technique, and on finding ensemble, and meditate on the meaning of the words, then when that moment of sweetness finally comes, it’s really very powerful. It’s kind of an ascetic ethos; we’re not ascetic because we don’t love good things or good feelings; we’re ascetic because we want them to be immensely better than if we just always follow the impulse.

Your settings of the three antiphons show a great deal of variety; no two sound the same, whereas most settings go together as a set.

I set myself the challenge to set the two psalms in their entirety. There’re not a lot of settings of that out there. I kind of think that composers feel that it’s daunting to use that much text.

What translation of the Psalms did you use?

It was my dad’s. (The Psalms of David, by Donald Sheehan) I fell in love it, and not because it was my dad’s, but my experience of trying to set my dad’s Psalms was that I didn’t need to do anything other than just find what I thought was the rhythm of the words. The phrases basically composed themselves. My dad was really aware of the rhythm of texts and the intricacy of rhythm and cadence in the Psalms.

The pronunciation of the text seems to be a challenge particularly in America. What do you see as a solution to pronouncing English in an American context?

I very explicitly told the choir not to flip or roll their ‘r’s ever. A few members of the choir found it almost impossible not to flip the ‘r’ – it’s just so engrained in them. I’m definitely a believer in American diction. I think it’s a myth that a flipped ‘r’ is better for singing. I think American vowels are beautiful when they’re sung well, and American English is what we do. Part of my goal for the diction on this recording was that it’s understandable without a text in front of you (I think we achieved that for the most part) and that it sounds approachable. Part of that means that some of the diphthongs are a little longer and some of the consonants are a little longer. I think singing liturgical music in English in America should sound more approachable – it should sound like how we talk. Maybe a higher form of how we talk, but still American. It should sound good to the people that are listening. It should also sound in tune. I love some of these shape note choirs that sing in an obvious Kentucky accent; if it’s done well, it can sound beautiful. We don’t have a “King’s English”, so we should own it. I would strongly discourage a church choir from using obviously British pronunciation.

Thanks very much for sharing your thoughts with us!

Some early reviews of the album:

“5/5 Stars… When listening to it I became wondrously aware that the magic of what Benedict Sheehan conveys so impressively with this world premiere recording, may offer to many, whether or not they are an active believer, a much-needed refuge… Benedict Sheehan must be congratulated for having added another work to the many already-existing versions of the Orthodox Divine Liturgy worth hearing and admiring… It is a balm for my, and possibly many other, souls; it is as intense as it is exquisite.” —Adrian Quanjer, HR Audio (France)

“4/4 Stars… A recording which succeeds fully as a musical work… Achingly beautiful… It is a work which commands not only attention, but respect, even if one has nothing in common with the religious teachings it imparts through song… This album is an addition of rare grace and refinement to the living music heritage of the Eastern rites. It will delight the Orthodox and the discerning non-Orthodox music-lover equally, and, perhaps, in its own way, contribute to greater understanding in a fragmented and disjointed world.” —Linda Holt, ConcertoNet

Order the CD+Blu-ray package here, or listen on your favorite streaming platform. Order the musical score here.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

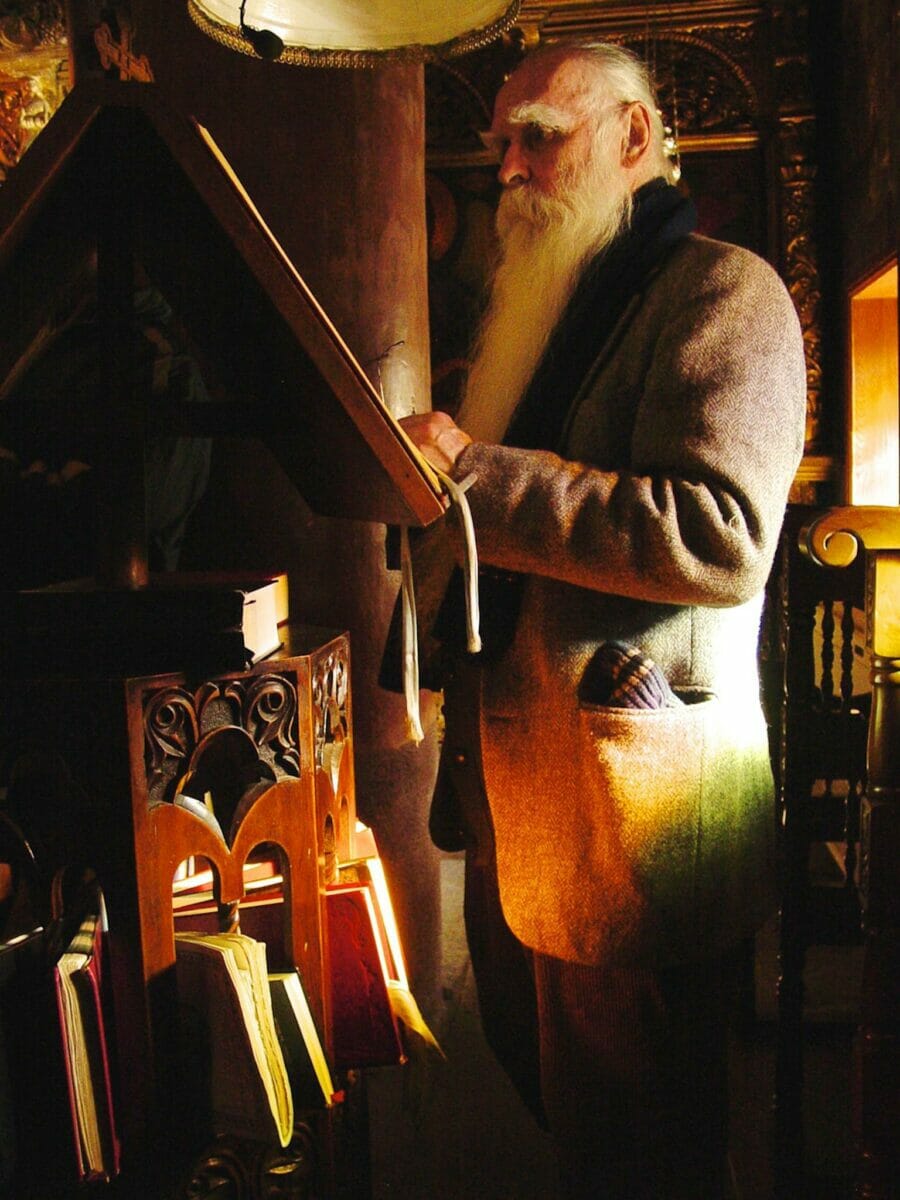

Thanks for this interview, Hamilton. I was particularly interested in Benedict’s comment about the reason for doing this – to set a high bar for everyone else to aspire to. I’ve often thought about my own work that way – particularly some of the fine inlaid furniture and extravagantly ornate icons I’ve worked on. Such items are incredibly difficult to make and will always be rare. I do not expect them to have much impact on the church’s liturgical experience directly, but as a point of inspiration, I suspect they will have a meaningful indirect impact. I know my own work has been heavily influenced by some of the impossibly beautiful liturgical treasures of past times. These are things that I could never hope to seriously imitate, and yet something of their beauty does shine through my own work.

The recording of Benedict’s Liturgy has moments of nearly impossible beauty. I nearly fell out of my chair when I heard the opening ‘Amen’.

Andrew, I love this connection. I’ve never thought in terms of rare and common objects, but I absolutely see the parallel. Thank you for this.

I might also add that when I compose church music, I often visualize the kind of space I think the music belongs in. Often, those end up being similar to—or sometimes identical with—spaces you’ve designed. It’s no accident that we decided to use the apse fresco from Holy Ascension on the cover. In other words, I think this notion of being inspired by “impossible beauty” (I could never hope to design a church) works across artistic disciplines as well as within them.