Similar Posts

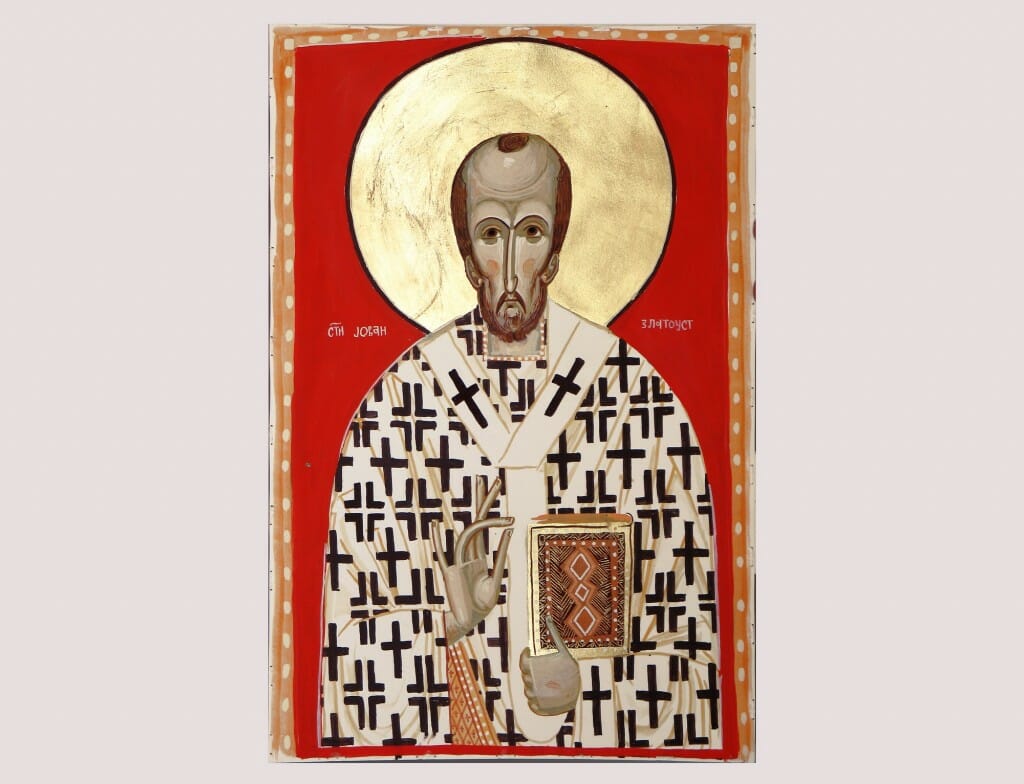

Since 2009, Todor has been a member of the international “Eikona” art group ( http://eikona.org/ ).

He has had eight solo exhibitions and exhibited with several international groups.

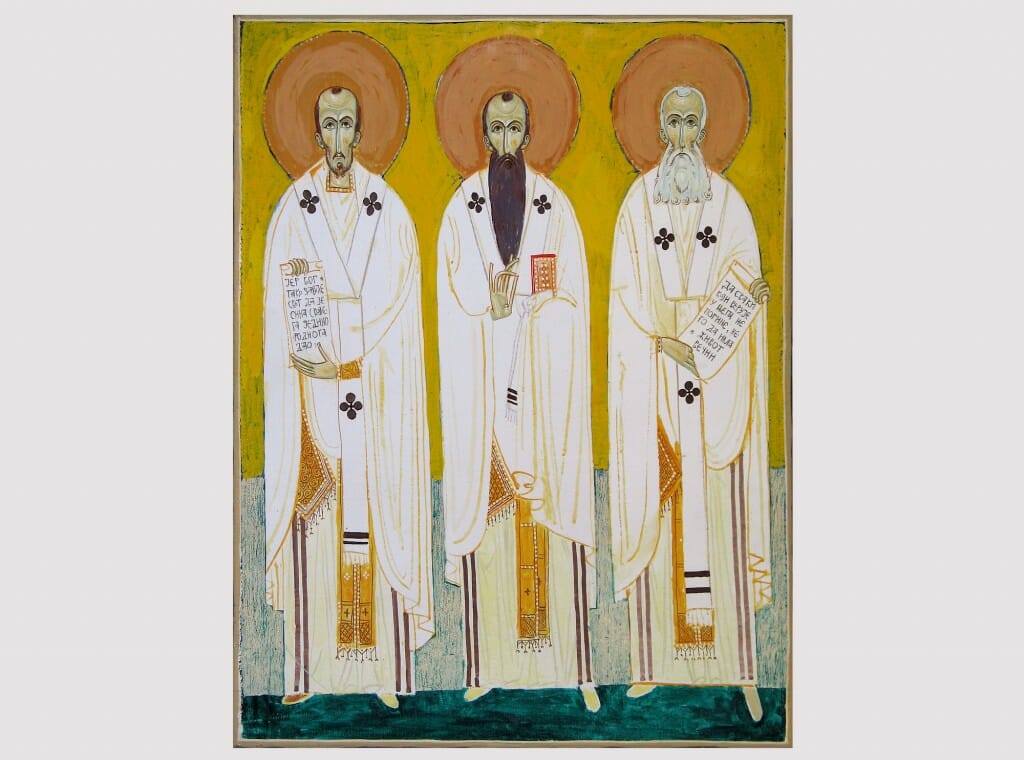

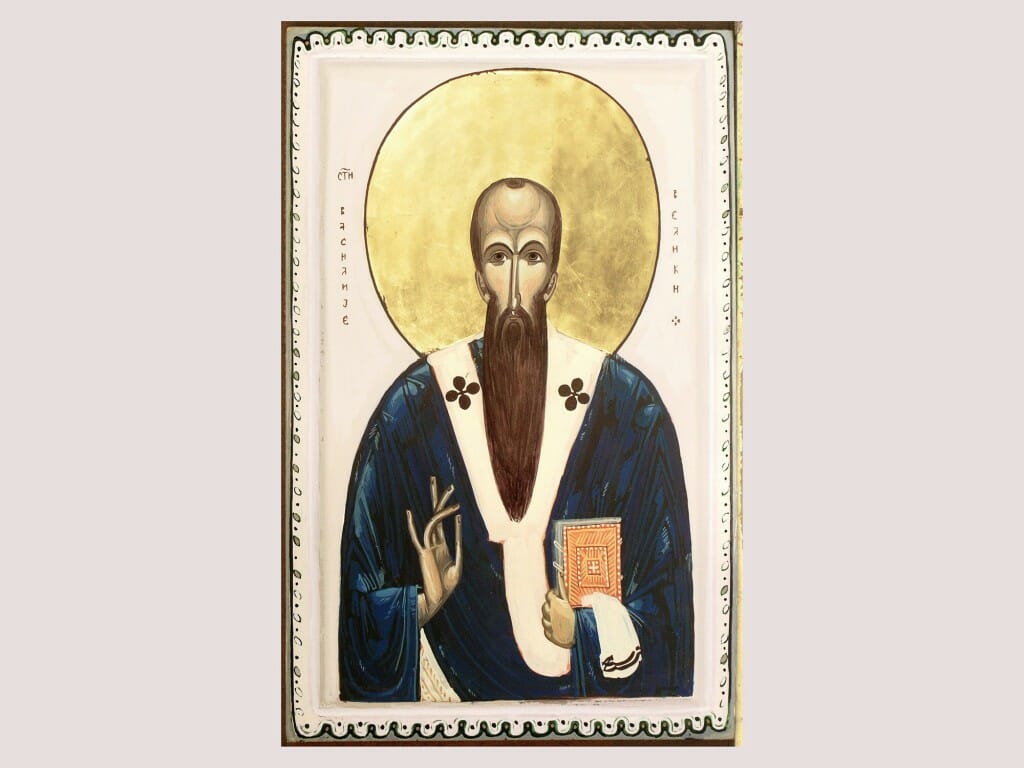

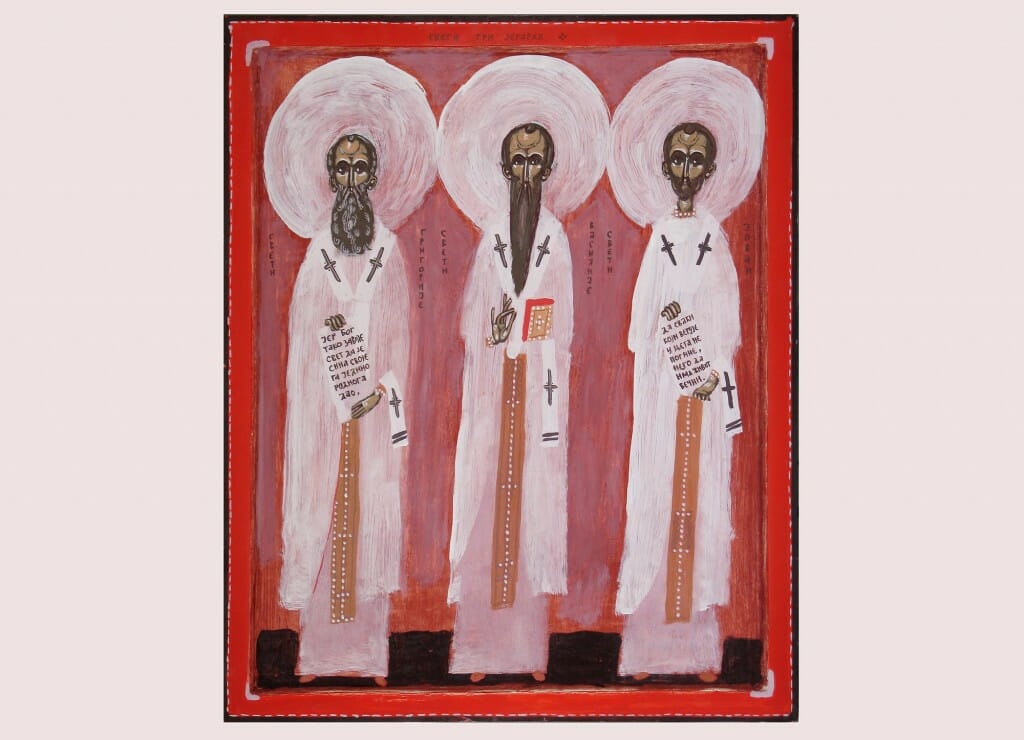

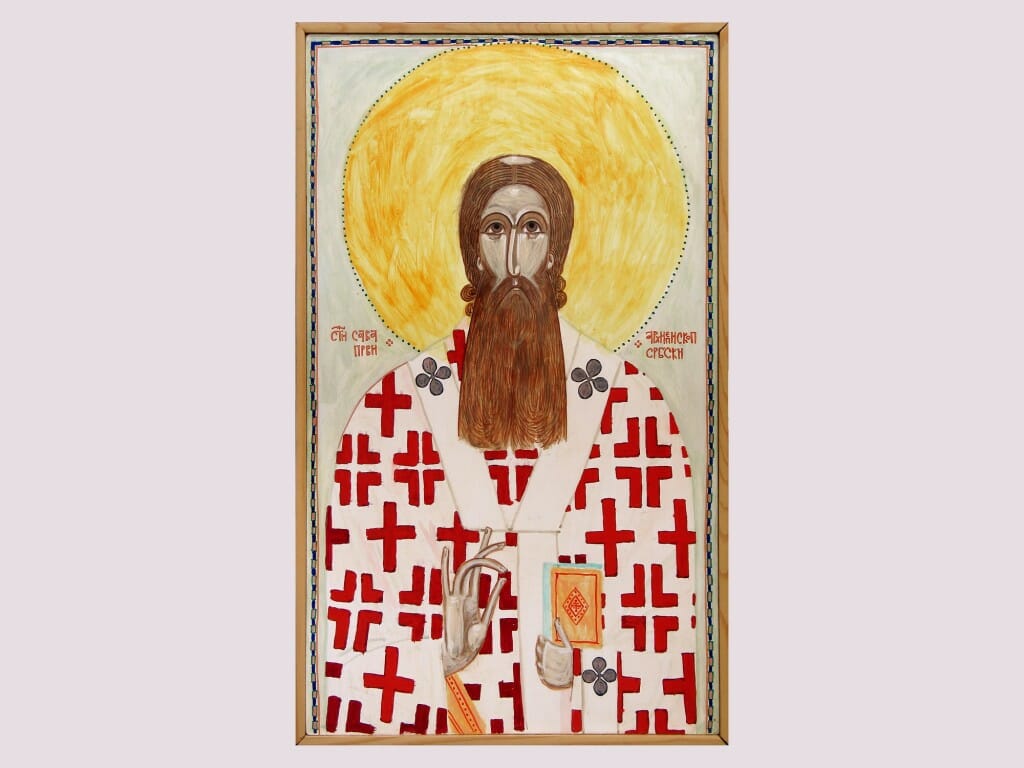

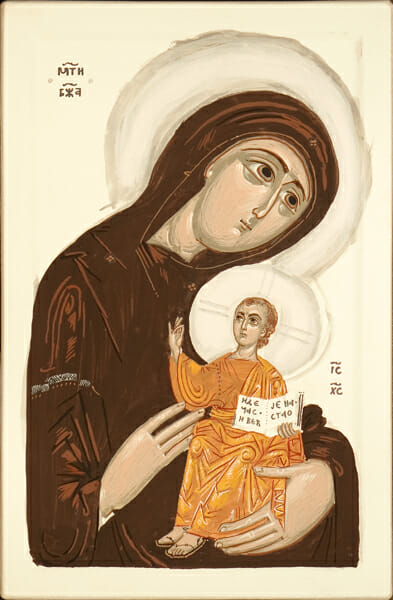

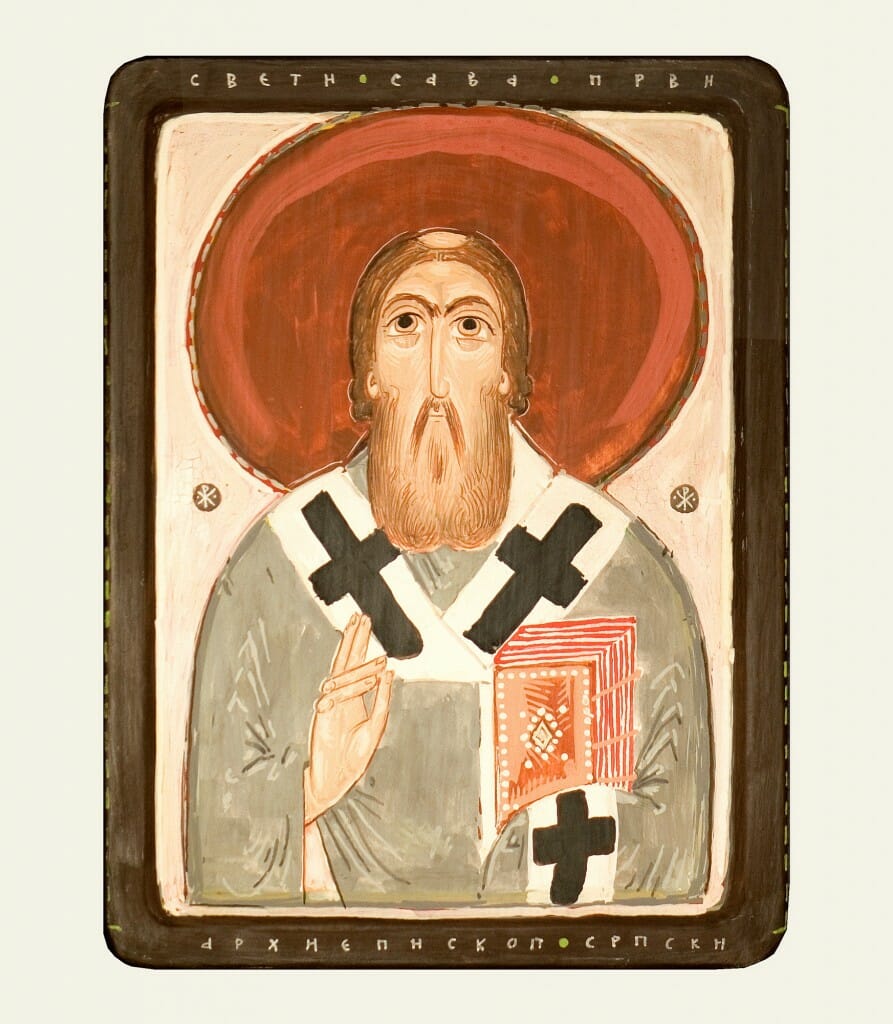

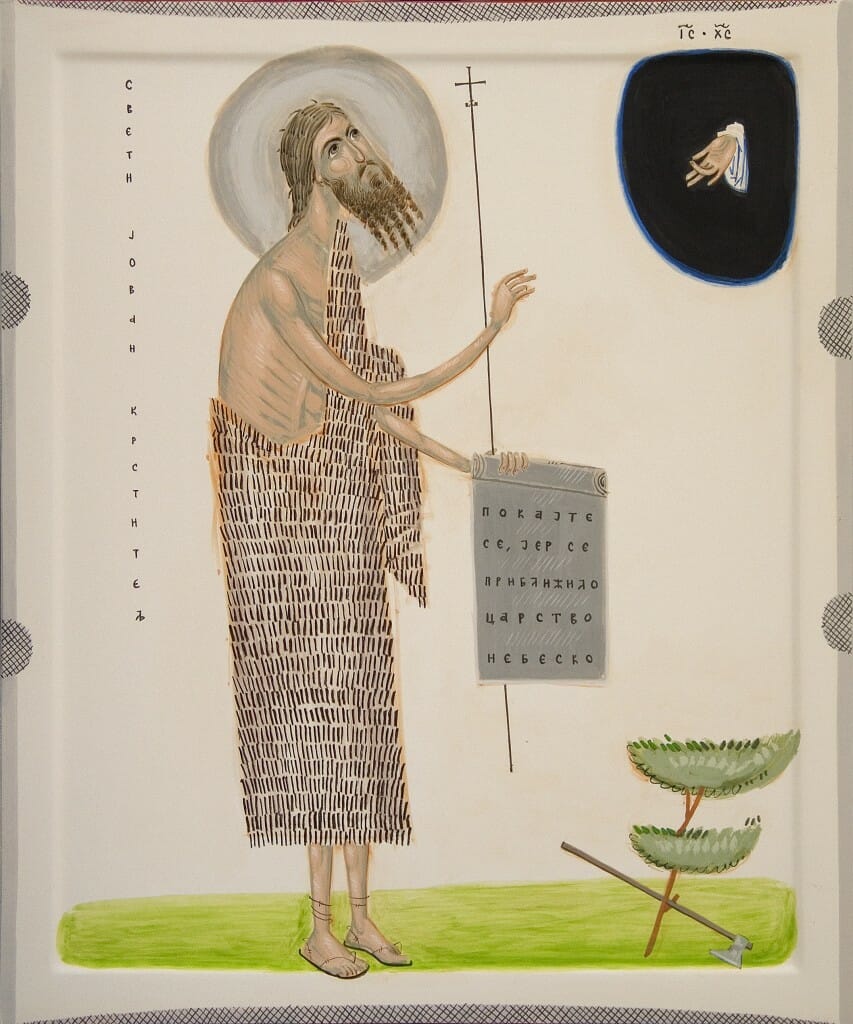

Todor is an active member of the Belgrade art scene and his secular art includes portraiture and abstraction. Although he has been painting icons since 1993, the themes of his exhibited work from 1999 until 2003 were abstract and secular as well. Through iconography, Todor’s intends to bridge the gap between church and contemporary art. The title of his Master’s thesis is Iconography As Contemporary Painting and through it icons have been recognised by academia as part of contemporary visual arts.

In 2002, Todor began teaching at the Academy of Serbian Orthodox Church for Fine Arts and Conservation in Belgrade (www.akademijaspc.edu.rs)

He has been an Associate Professor since 2007 teaching courses on icon painting at Bachelor and Master’s level and writing about church art. His research interests are art theory, art history (Byzantine) and international theology. Todor has published several articles, a book and participated in several international conferences about art and art theory.

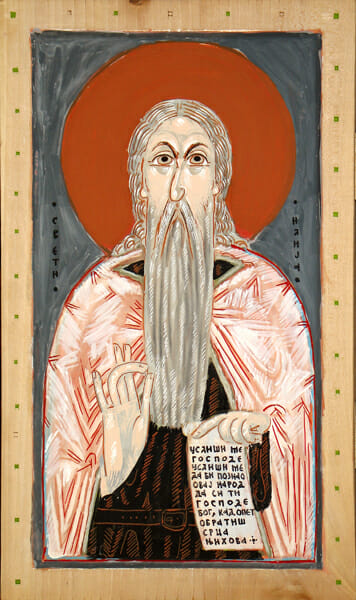

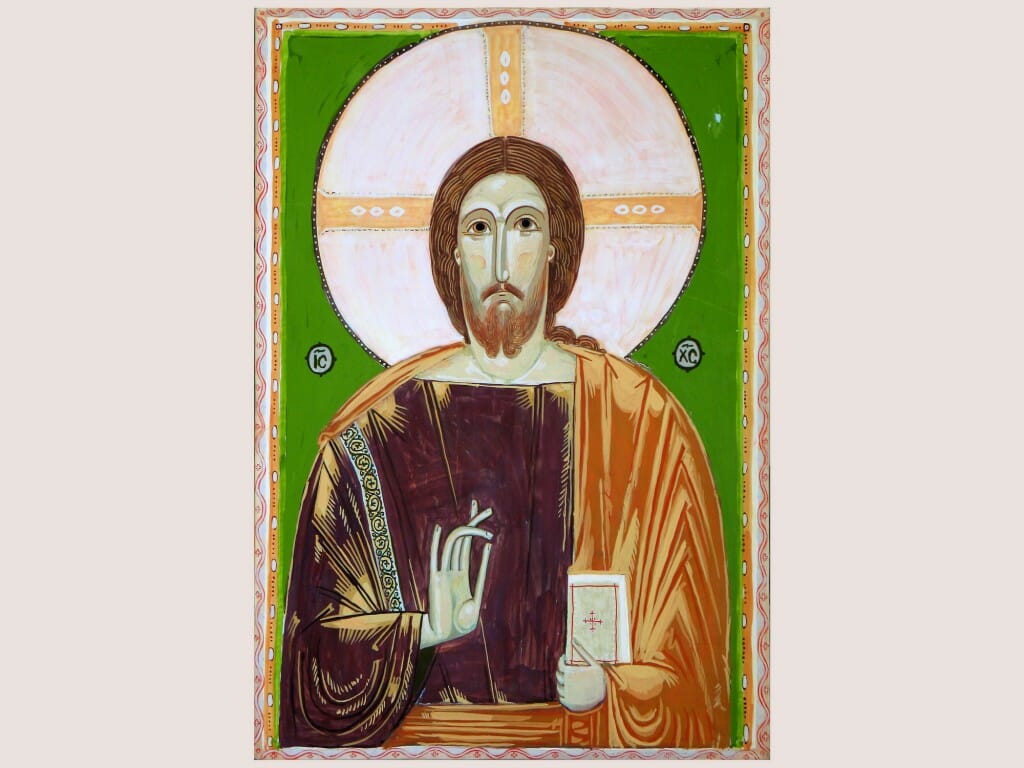

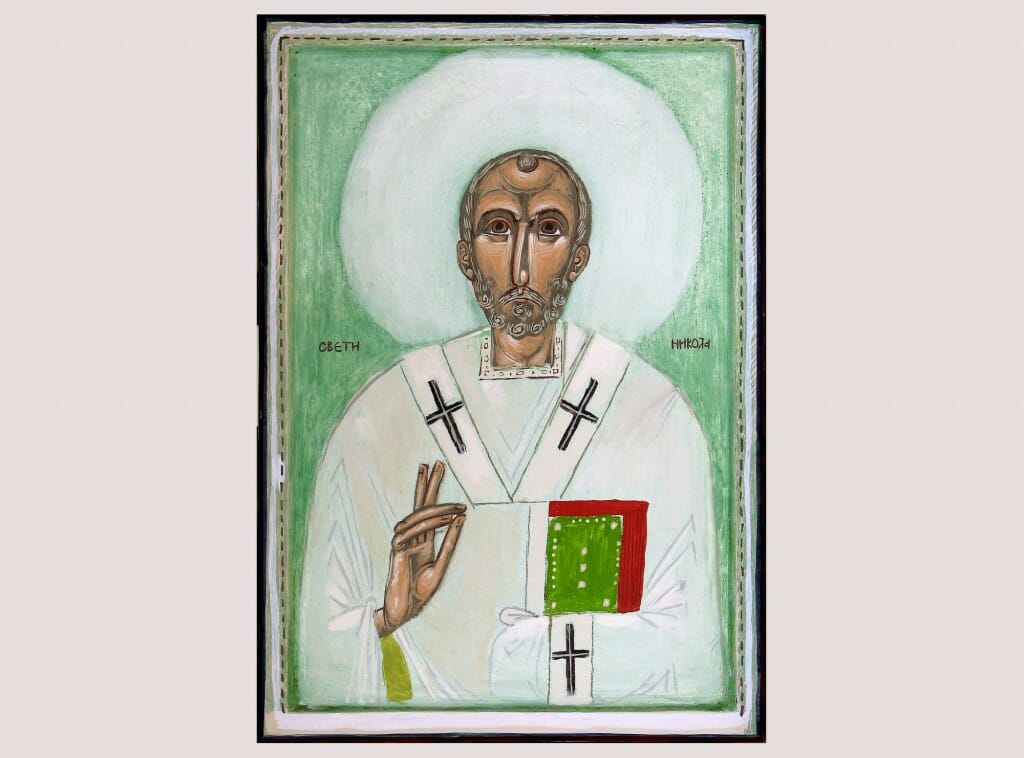

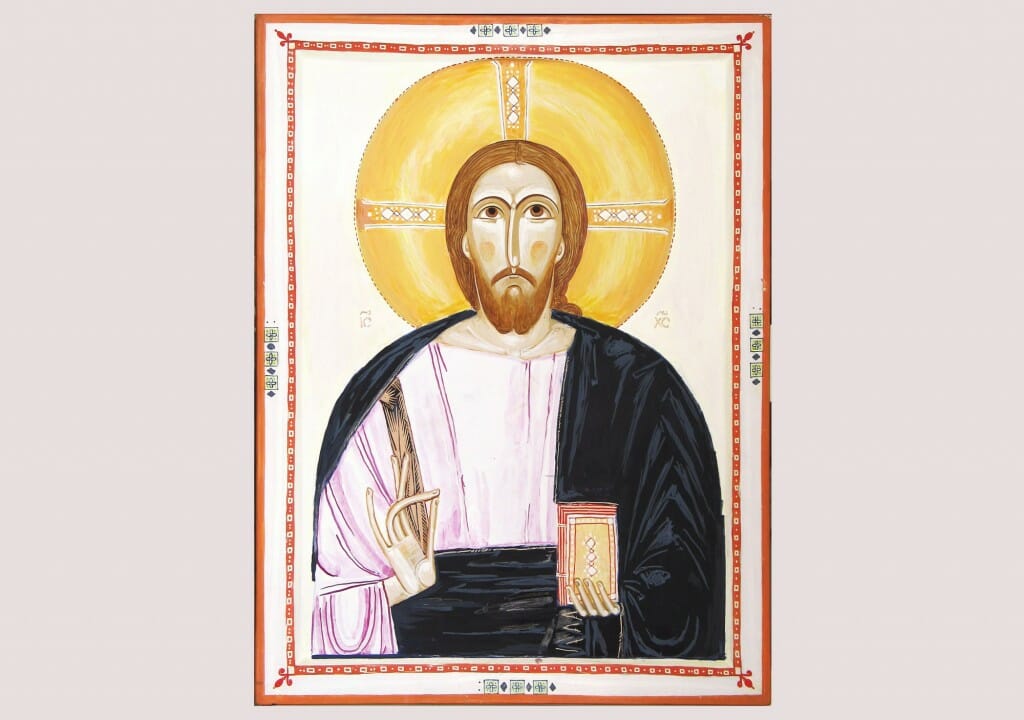

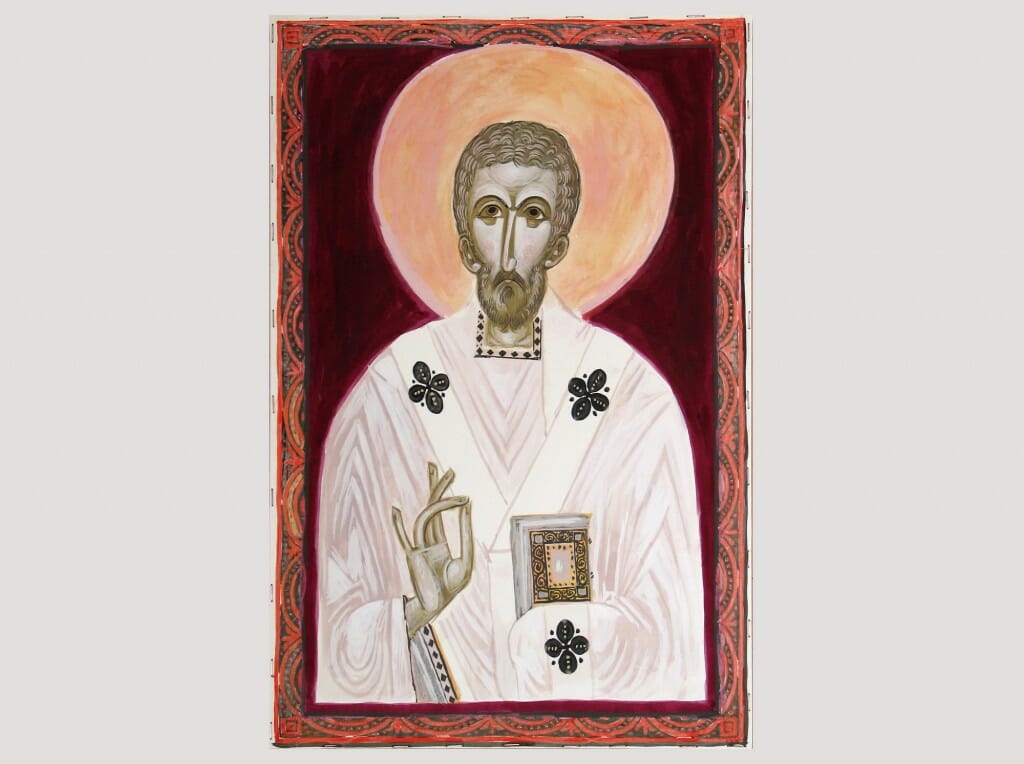

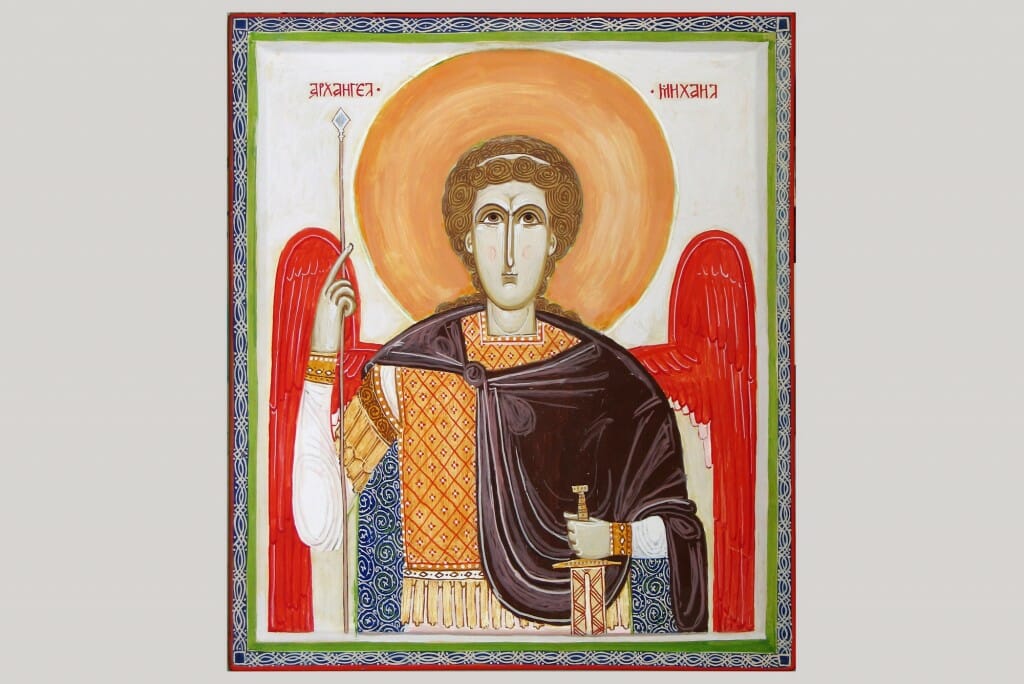

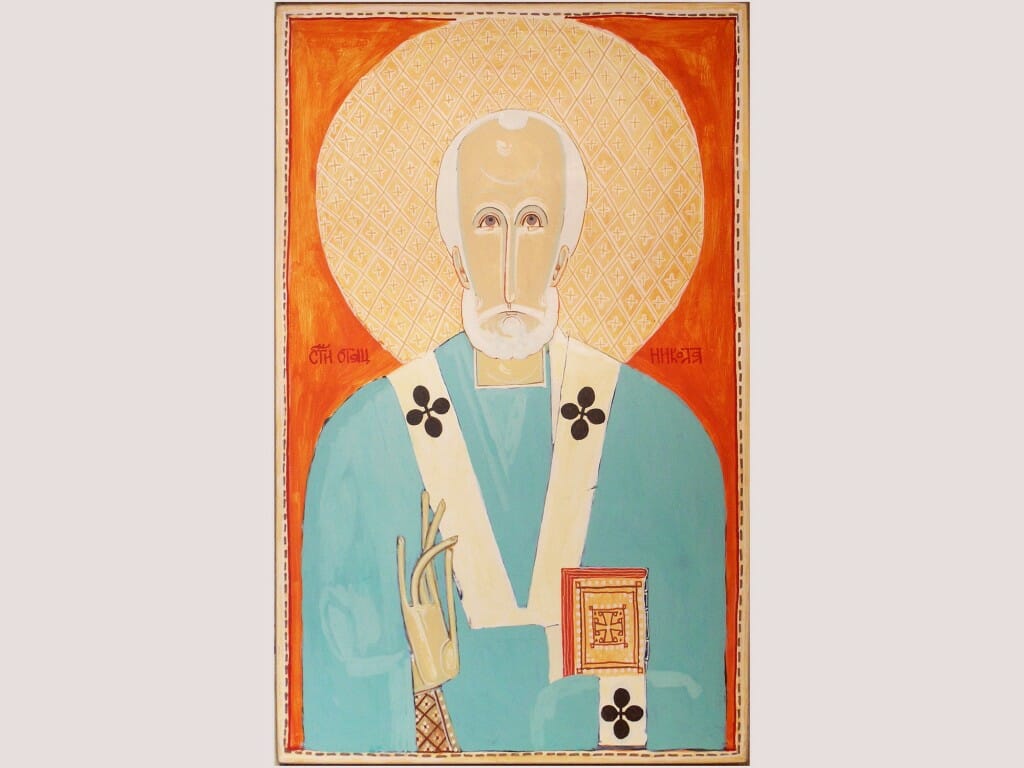

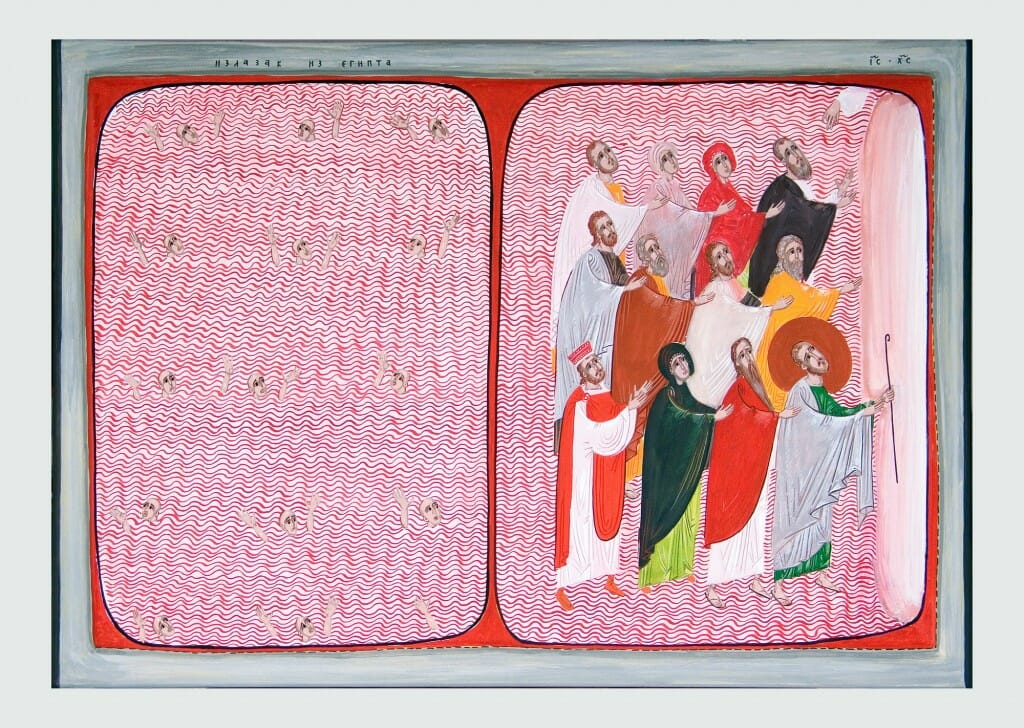

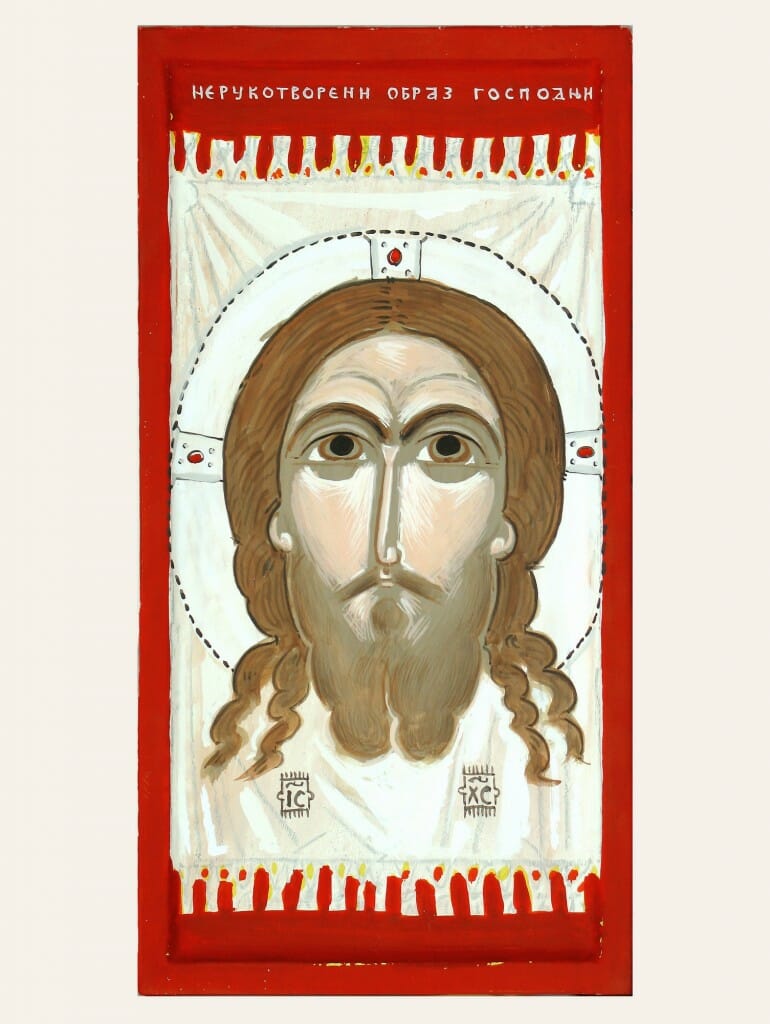

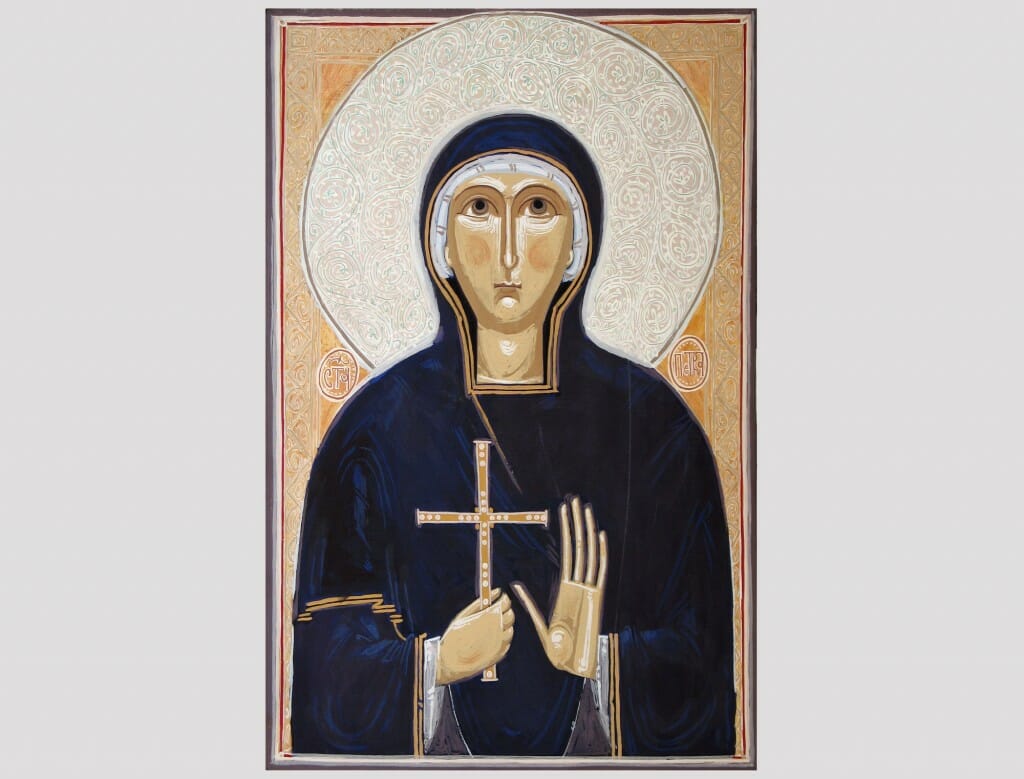

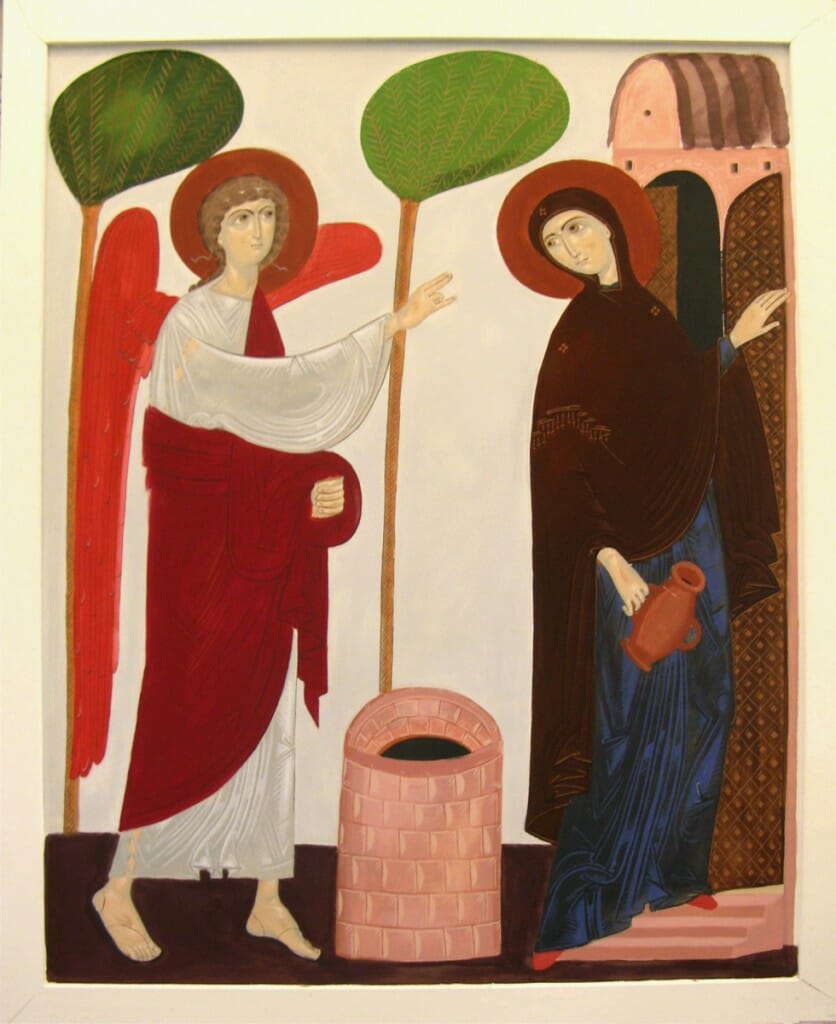

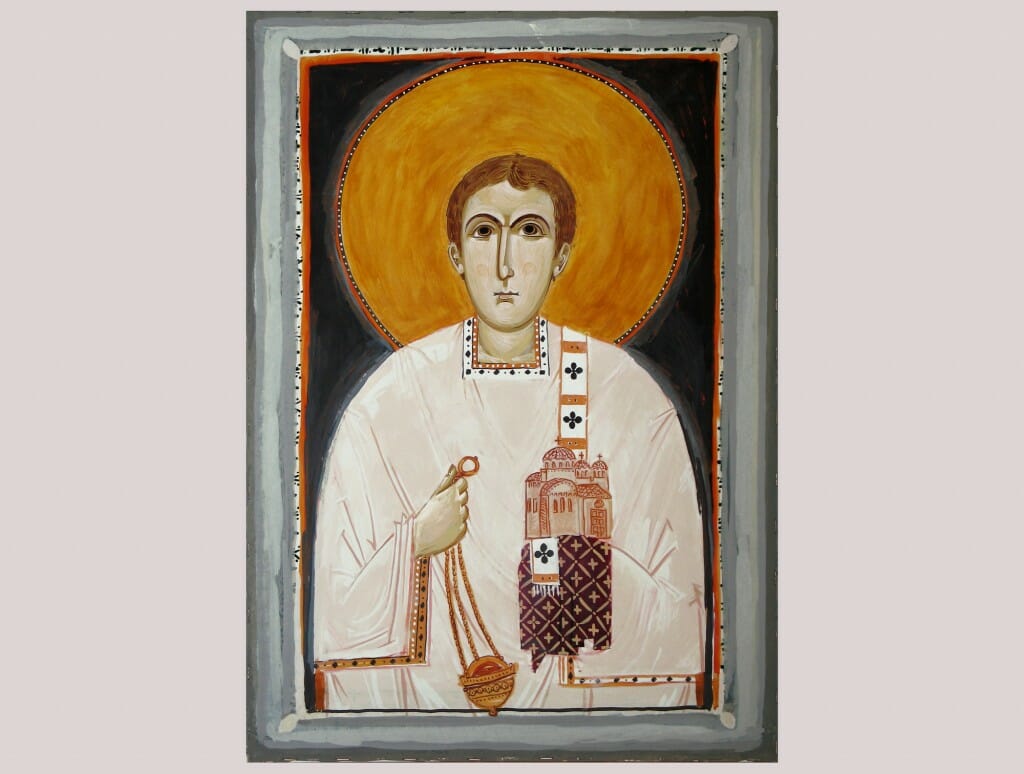

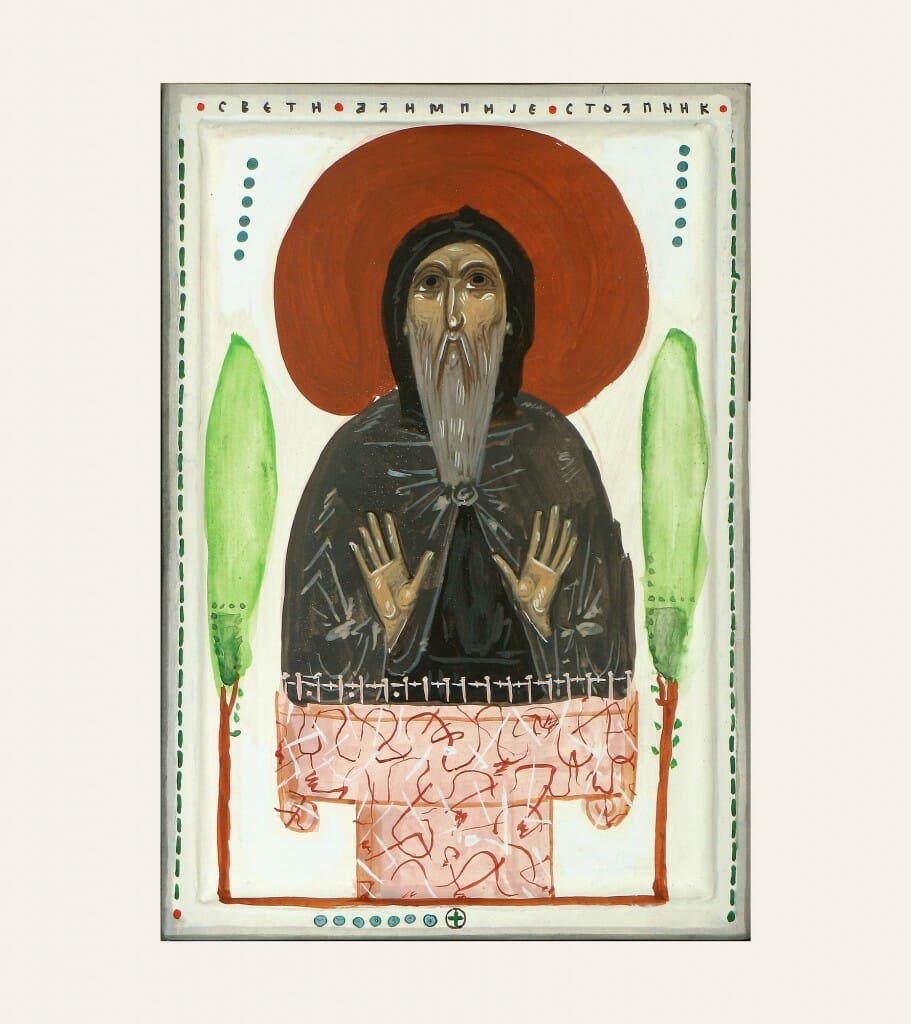

Todor’s work was first shown in Russia at the Third Icon Painting Symposium in Saint Petersburg during 2010 . His work stood out: he refused to copy the prototype! Art critics and iconographers frequently discuss concepts such as copying, stylization and imitation that are tendencies among contemporary iconographers. The remarkable quality about Todor’s work apparent at the St Petersburg Symposium in 2010 was that he refused to stylize his work to imitate an historical period. Instead, found his own language without loosing the image’s power of expression.

Tradition is apparent in his icons not as a set of rules, but as a living testimony to God in contemporary language. Although he has been dedicated to iconography since 2003, the connection between the artist and contemporary art has guided his research into iconography.

Todor’s images stand out from the fastidiously copied icons produced by the majority of contemporary iconographers. Todor’s work has power; it can be compared with catacomb frescoes that capture the essence of the early Christians’ reverence for the testimony of God.

His icons are informed by on-going research in theology and iconography and meditation about the current condition of icon painting. His work provides answers to several questions about Eastern Christian liturgical art, but nevertheless, at the forefront is his painting technique, which is similar to the medieval prototype.

Why did you reject the copying method, based on tracing, especially as it was used in Serbia when you started painting icons?

Important decisions in my artistic life usually occurred in the company of books – or, let’s call it theory. I was lucky at the time I began icon painting as some of the theoretical work of Father Stamatis Skliris had been published in Serbia. He is an unusual and inspirational Greek icon painter and I was influenced by his theoretical work, inspired by his theological education. In short, he applies the achievements of neopatristic theological synthesis to contemporary church arts and I realized the authentic approach to this kind of art has a theological and ecclesiastical dimension. Among the core ideas of neopatristic theological renewal, I’ll refer to the thought of Father Georges Florovsky who identified the goal of contemporary theology as not simply turning back to the fathers, but turning to the spirit of the fathers or to the mind of the fathers (The Collected Works of Georges Florovsky, Volume 4, Belmont, MA 1975, 15-22).

I’ll illustrate this concept: if somebody learns the writings of Saint Basil the Great by rote and recites them in a public place, does this person become a theologian? God save us from this! Even if such a hypothetical person understood St Basil’s writing, nobody would ask him to recite the texts. Why then is a similar thing expected of painters? The Medieval Church never asked painters to reproduce the work of great painters or epochs, but simply to reproduce the faces of saints, and events about the history of salvation. Style was never mentioned by Byzantine theology except in the domain of artistic invention. If it were otherwise, Medieval Art would have lacked stylistic development.

In the Middle Ages, artistic style would change radically in a few decades, and yet we observe unchanging style in the icons of the 20th and 21st centuries. It would seem apparent we have not understood the spirit of the fathers where church art is concerned. In my opinion, the same spirit of art we proudly use as our role model teaches us not to copy.

Of course, this statement is polysemic because we don’t know enough about the authentic spirit of Medieval Art, and the practice of copying is a contemporary and unrefined one, incompatible with Medieval aesthetics. In my opinion, church art, approached through its liturgical perspective, must be brought to life by people in actual time. This also means it must be brought to life in an actual cultural context – comparable with, but – at the same time – incomparable with, previously existing cultural contexts. We are invited to transform this actual cultural context however impossible it may seem. Imagine how impossible it seemed during late antiquity to change Roman culture with its demi-god emperors? Christians did exactly this due to faith, and God’s help. It is not expected of us to express the faith of people who once lived on the land we inhabit today, but instead – our own faith. We cannot go to church and say, “God have mercy on us because we are the descendants of pious people who lived here before us”. And this is an illustration of the way contemporary church art is conceptualized: since we do not have the talent, or do not understand what to do – or maybe we simply do not have enough faith – we can only more or less reproduce the art of our forefathers. This position is described as indicative of the modesty of artists, and expresses the highest possible respect to our great tradition. From my point of view, this position lacks humility and modesty and is irresponsible ecclesiastical and artistic behaviour. No matter how primitive and rudimentary our expression is, it has to be done from the heart, through the mind and body, otherwise we are avoiding the responsibility of being part of the Body of Christ. Such expression is part of our attempt to make the Body of Christ present, which is, when speaking about art, making it visible in a material and cultural context. This is why all we can give, all our talent, must be included in the process – otherwise we are denying our skill, burying talents to the ground (to use the Gospel parable), and at the same time doing little more than telling pleasant stories about the Middle Ages.

Is there such a phenomenon as the contemporary icon? If so, what are the elements informing it?

This is a serious question and one to which I cannot give a positive answer. We cannot accurately perceive a future point of view or analyze our epoch from a distance, but we have archaeological experience helping us understand our actions today. The problem is every icon painted today is contemporary. Problems arise when somebody thinks they are painting in the Medieval manner and that there aren’t differences between icons painted today, and those painted in the Middle Ages. Painting an icon the Medieval way today includes contemporary skills, devices and processes completely unknown to Medieval man.

Starting at the beginning, icons are (1) discovered, classified and categorized by art historians; then icons must be (2) cleaned, conserved and restored in order to be seen in their full beauty after which they must be (3) photographed and (4) published, in order to be available to the public. The public includes contemporary iconographers some of whom live in urban centres where those icons are (5) exhibited in a museum, enabling close observation, under good light conditions. If you want to make a real Medieval icon, most of those five, and possibly a few more procedures have to be fulfilled and I ask – can anyone find anything Medieval in any of those procedural steps? Producing a Medieval icon today is a high-tech and contemporary procedure, not only technologically, but also at a conceptual level.

Let me give you an example. When Father Zenon changed his style, skipping centuries and painting icons in the 12 th century manner, it was artistic behaviour unimaginable in the Middle Ages. For such a process you need the help of all five high-tech procedural steps mentioned previously, carefully orchestrated by an artist highly trained in art history and mimetic drawing/painting skills. Needed also is a public audience trained in the hyper-dynamic experiences of 20 th century artistic exchange able to respond positively to dynamic aesthetic developments. These possibilities were not available to artists of the Middle Ages. So, from the beginning, we should be aware of our contemporaneity, and try not to live in the Middle Ages, because from an artistic and theological point of view this is irresponsible. The Middle Ages said much about art and spiritual life but artifacts and information from the time won’t speak to us if we do not enter into the dialogue from our own position.

As with any dialogue, if you pretend you are somebody else – and especially if you believe you know everything the other side has to say – then forget about a dialogue. As with all great art, Medieval icons are full of sophisticated messages and we can speak with them every day, and (exactly because of this) it is almost an insult to treat such depth as a surface to be copied. Old icons are copied because we recognize their depth, but if there is the possibility to learn the language they speak (instead of transcribing visual text we do not understand) it is irresponsible not to explore such a possibility. Learning this language should be our starting point: only when we use this language in creative ways (and it’s similar to the way a poet uses it while writing hymnography) can our icons become actual theology in color.

So finally, my answer to the initial question is: we cannot escape being contemporary in icon painting, but it is up to us to decide how to use our contemporary position. Are we going to use it as an artistic/technological process to hide our spiritual confusion, or are we going to use it as a way of an active Christian being in the world?

How do you create a bridge between ecclesiastical and contemporary secular art in your work and why is it important?

For me the question of importance came before the question of ways of artistic execution. My opinion about the question of importance is radical: it is impossible to create authentic ecclesiastical art if we do not engage in a dialogue with contemporary art . It is not an artistic question, but a theological one. We could spend pages of paper on this question, but let’s try to discuss the main points of the argument. The Gospels teach that God did not send his Son to suffer incarnation and death on the cross in order to save only the elect and perfect. However hard the notion may seem, the church is not trying to save herself but the whole world, so the Gospels must be available to anyone and everyone in any language. This is the reason not a single Gospel was written in Hebrew or Aramaic, though Christ Himself spoke these languages. The Gospel is good news for the world, not only for our small community, however pious.

The same thing applies to painting: we don’t paint icons only for ourselves, but for everyone, even for those who are not yet born. Moreover, on the pictorial level, the language of contemporary art shapes the way contemporary man thinks and is the only universally recognizable language we have, however imperfect. Parallels with spoken languages are not the only available criteria, of course, and I’m not suggesting we need to discuss every crazy idea emanating from the world of art, or apply it to icon painting – God save me from this! But there are many good and useful artistic inventions occurring before and after the Orthodox Church rediscovered its Medieval artistic heritage at the beginning of 20th century.

After all, can we be sure our artistic heritage would have been rediscovered if avant-garde movements from this century had not happened? An academic and conservative assessment of that period describes Byzantine and Russian Medieval icons as naïve but on one of his visits to Russia, Henri Matisse said, after seeing Ostroukhov’s collection of icons: “… what clearness and display of great, strong feeling. Your young people have here, in their own home, far better models of art than abroad. French artists should come to study in Russia: Italy offers less in this field.” [Alison Hilton, Matisse in Moscow , Art Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Winter, 1969-1970), 167]. We must admit he was one of the few people destined to change the world of plastic arts and consequently, redefine our contemporary visual horizon. So, should we say: Thank you Henri for helping us understand, but now go to Hell – we don’t need you any more! I suggest a different option: If we want to do something evangelical with our Church art, then we need to learn the language of Medieval art and the language of contemporary art. We need to identify the achievements from the second and use them to inform the first. This is the only way the renovation of Medieval art can become the authentic pictorial language of the church, and not some archaeological or museum project, produced for experts or the elite and overlaid with the pious aroma of Medievalism.

Finally, there is a simple liturgical argument about this subject: If our art has a liturgical dimension, it is necessary to bring elements of our own world to the church in order to save it, the world and also – ourselves. We don’t need Medieval carriages, horses or costumes to come to the liturgy; we don’t need Medieval varieties of grapes and grain to produce wine and bread for the Eucharist. We don’t need Medieval rhetoric to explain the Gospels to the people, and finally, we don’t need to recite the homilies of Saint Basil by heart. We need the opposite: if we do not bring something of our own to the communion of Christians of all ages, then we are not wholly taking part in the Sacrament. We are not actors here – but a complete and complicated people with bodies, souls, minds, knowledge and experience. If there is nothing of our visual world here, then part of us is missing. The experience is inauthentic – inside the church/liturgy we live one life complete with Medieval elements and outside – there are other realities. We do not need elements from the Middle Ages in our churches and icons but we are reluctant to sever continuity with this great epoch of church life and faith. And, such continuity will not be achieved through imitation, but through understanding the spirit of our Medieval heritage. We must bring our knowledge and dilemmas to the purifying fire of liturgical and ascetic experience, thereby making this heritage alive in ourselves and in the world God has brought into existence.

We know iconography has changed with church history, how do you think it will continue to evolve?

This is a profound question. Theologically speaking, it is easier to explain what God is not than to imagine what He is . The apophatic answer to your question is simply this – if icon painting is a creative and personal process, then it is impossible to think about the future in positive or positivistic terms. From such a position it is easier to understand why contemporary icon painting is stubbornly resistant to change: some of us are happy being told what we do is good, that the future holds few surprises or disappointments and we can remain ignorant of our mistakes. On the other hand, the unpredictable nature of artistic endeavor is a problem whenever we try to conceptualize it. Personally speaking, I am more concerned with what should not be done than with positive statements. I don’t think we can achieve the stylistic unity possible in Byzantine times, but I don’t think we should strive for this. Immediate stylistic recognition of icons and frescoes throughout the Byzantine Empire was an element defining its Christian and imperial cultural identity. I will insist at every step of our discussion that the differences between Medieval and contemporary culture have to be taken seriously if we want to be sincere about church art and church life in general. Christian culture today has a different basis for preaching the Gospel and is under no obligation to rely on centralized imperial power networks. Maybe a stylistic lack of unity would be the way to express – through the plastic arts – the openness of the Orthodox Church to all people from every corner of our confused world. I don’t know if this proposal would work, but the question of stylistic unity needs to be discussed.

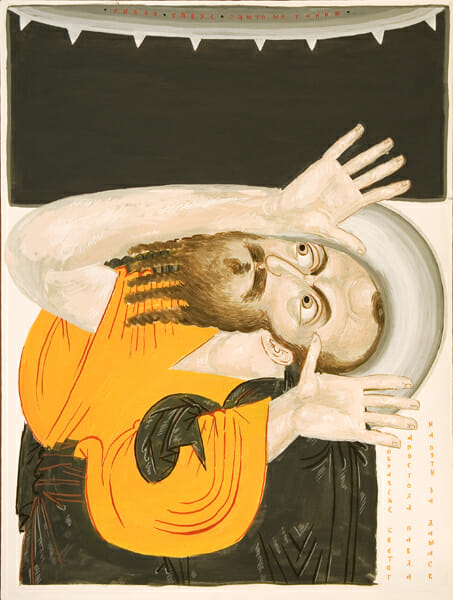

I’m more convinced when it comes to my next proposition: church art should carefully rethink the function of complicated narrative cycles included in icons and especially, on the walls of churches because we are literate and inundated with a variety of narratives every second of our existence. Especially persuasive are the forms of mobile visual narration – in films and video games. Trying to narrate the sequence of events through static pictures to a literate audience misses the point of the medium. If we put icons in competition with films and video games, we miss the point. Church art – in my opinion – should strive to offer something different: the simple and solemn, static picture/vision radiating with inner power. The simple and static picture/vision full of layers – on a pictorial and theological level – can be watched for hours. The simple and static picture/vision capturing the eye of the beholder, body and soul, mind and heart, with such strength the person would not want to leave. And finally, the simple, static and solemn picture/vision is so different from the informational melting-pot rumbling around beholders every single moment of their lives, they will be convinced they have entered a world transformed by God’s grace and love. Icons must be great art not because somebody wants to be greater then somebody else, but because only great art can express so many messages in one single picture/vision. I’m not convinced any of us have the potential to realize such a picture/vision, even partially, but I’m convinced it is worth striving for, and I believe miracles happen – even today.

Your PhD research includes chapters about Medieval concepts which the contemporary renewal of church art has not taken into consideration, or has interpreted inaccurately. Would you describe some of these concepts?

Although my PhD thesis was concerned with contemporary icon painting, it changed direction to include research on Medieval art. Through previous research into theory and practice, I realized we do not know enough about this subject. We know a lot about the Middle Ages, but our knowledge is insufficient when it comes to making decisions about contemporary church art. It is insufficient because it does not help us produce art that is not a copy – our art must be recognizable as an authentic scion of great Medieval art.

Contemporary art historians have contributed much to increase understanding about the function of icons in the Medieval context and once we understand the reasons for those artistic decisions, we will be able to make our own decisions. More importantly, we will be able to define which Medieval artistic conventions are applicable today, and those irrelevant to a contemporary context.

I don’t know if much of my doctoral research on this matter is useful, but some aspects of Medieval art are clearer now, at least for me. For example, the kissing of icons was not a regular part of liturgical practice during the first millennium of Christianity. On the other hand, ritual kissing between laity in the nave and between clerics in altar during the Eucharistic kiss of peace was usual. However, by the end of millennium the kiss of peace ceased to be given in the nave and was restricted to the altar as it is today creating distance between those two liturgical spaces. The clergy was responsible for this development, arguably resulting in distancing laity from tactile participation in the liturgy.

On the other hand, in the 12th Century, wall decorations became accessible to laity, as paintings were included in lower areas previously covered by marble and icons were placed in important locations, around the altar screen. Interestingly, during this period the ritual kissing of icons officially entered liturgical practice and moreover, it seems icons were used to close the gap created between the nave and the altar.

The late Medieval Church preferred visual to tactile communication between those segregated spaces. The visual separation of the altar from the nave through enclosing the sanctuary with a barrier represents the conclusion of that process. The icon became recognized as reparation for increased liturgical segregation. From such cognitive heights, late Byzantine art was invited to comment upon and explain the liturgy, and to represent previously invisible aspects of the Eucharist – the Transubstantiation of the Body of Christ – described as Melismos – in iconographic terms.

Through this context, the relationship between the human body and icons acquired a special kind of dynamic. The way icons were depicted influenced human behaviour especially in relationship to the human body, and, in return, human behaviour and human physicality influenced forms of artistic expression. To elaborate on my conclusions, we would need more time and space than this interview permits. Moreover, I have not researched the ways those conclusions could be interpreted by contemporary church art, as something has to be left for the future.

Only one interpretational direction seems apparent to me at the moment: the problems icons were expected to respond to in the Middle Ages may not be compatible with those of concern to contemporary church life.

What is the most important dimension of the icon? What tasks do you set yourself when you paint an icon?

The first responsibility is to give our best every time. Every time we paint, we must bring everything we know – our energy, creativity and experience – to the painting surface. It is our Christian duty. The second responsibility is included in question 6: It is not possible to create ecclesiastical art if we do not engage in a dialogue with contemporary art.

At this point I need to emphasize the ways in which this should be done. I won’t discuss the ways I have been trying to do this, because it is impossible to describe in positivistic terms. Moreover, no one can be (or should be) confident they have produced the best possible outcome to this challenge. As far as I am concerned, finding ways to resolve this challenge is one of the most important responsibilities of icon painting today.

Artists need to find the most appropriate way to bring the tradition of iconography to the contemporary aesthetic context. Not everything from contemporary art can find a place in the icon, but, on the other hand, not every artistic convention from the Middle Ages is necessary for contemporary ecclesiastical life. The demarcation and the dialogue between the icon and contemporary culture cannot happen in theory and, consequently, does not belong to the doctrinal aspect of church life. Instead, it represents the most important task of the icon painter.

My opinion is that the only way to find ecclesiastical balance in this cultural-theological dialogue is to let artists explore both aspects. We can’t make theoretical decisions; they must be substantive pictorial proposals. If we want reasoned proposals, artists should be equipped with theological knowledge, liturgical and ascetic experience, and an education in the arts and history. The church should encourage this.

This brings us to the beginning of my answer, where I said that we must work hard and give our best. The third important responsibility is to be critical about our work. I am trying, as much as possible, to be a neutral beholder, while painting. This means during the artistic process I’m trying to judge my work as if done by somebody else. This is the only way to use all the equipment I have already mentioned for the realization of the second important responsibility. There are other responsibilities that could be categorized as important, but let’s stay with these.

If we take the first responsibility seriously, then everything becomes important – every brushstroke becomes the reason for making crucial decisions. This is exactly the way it should be, but trying to conceptualize it is not the way to conclude our discussion.

What is the most interesting and most difficult ?

The most interesting is discovering new artistic solutions. The most magnificent moment is when something new happens unexpectedly, and you realize your role is to recognize this new quality and leave it there.

In such a moment you are happy like a little kid discovering the beauty of the world, without the dust and grime that will cover it during the years of growing up. This creative relationship with life is something artists can bring to the church and, in my opinion, it has a deep theological dimension. It is not a coincidence that only three holy fathers have the title Theologian in their names – Saint John the Evangelist, Saint Gregory and Saint Simeon. They were authentic poets in the theological context of their time. There is a mystical connection between theology and the arts that, in my opinion, can’t be explained through reason.

And about the difficulties: From my point of view, the most challenging experience occurs during the painting process, when you start believing you don’t know anything, and all your experience is worthless. If you work hard and paint authentically such a crisis happens frequently – with almost every icon. I tell students, when they have a crisis, that it is normal, not pleasant, but important and a good experience. If you don’t survive the critical moments while painting an icon, then you should be suspicious about your position. It is easy to flatter ourselves and try to avoid a crisis and criticism – and, of course, painfully human.

How does contemporary technology influence icon painting?

I think we have answered part of this question. However I would like to make a positive statement about the contribution of contemporary technology in church art – that is, the expansive palette of contemporary pigments. Chemistry has enabled us to investigate the material world with depth and our existence in the world has acquired a new coloristic dimension. We need to explore this new dimension with caution and incorporate new colors gradually into our icons. Otherwise, our results may seem naïve, leading us to conclude that technology brings nothing good to Ecclesiastical art. In my opinion, Russian artists use the contemporary palette in a more subtle way compared with the examples from Serbian and Greek Church art.

However, to avoid using this treasure is not a wise decision. Gold and precious stones are incomparable with rich and sophisticated color combinations that bring radiance and splendor to icons. From a technological and artistic point of view this radiance is a product of the human spirit. In my opinion, human radiance is a better symbolic and aesthetic vehicle for making our churches Heaven on Earth than the glittering of actual gold and jewels. In closing, as far as I understand the spirit of Medieval art, I think the Byzantine masters would enjoy using our contemporary pigment palette.

I believe there is a consciously generated philosophical and visual system in whatever an artist does. As master, the artist can explain every movement of the brush but how does he or she find solutions to problems?

Although I’d like to bring everything to a conscious level, I admit this is not possible. The passion for thinking and reasoning can be dangerous and irrational as is every passion. My experience suggests there is a borderline – not always clear and recognizable – that appears whenever I think about visual form. The borderline is where discursive thinking stops, leaving a space for another kind of thinking – one without words – thinking in colors, shapes and lines.

This is a place where experience of abstract art helps a lot and (in my opinion) it is the intersection between icon painting and contemporary art. I cannot say much about this or provide a methodological description of my experience because it occurs in the realm of pictorial language.While arising in a non-discursive area, elements of this language – at the same time – produce faces, figures and scenes, returning us to the pictorial level informed by theory (theology, history, philosophy, etcetera).

In terms of artistic method, I focus on the border between concepts and pictorial language that determine the raw material of artistic expression. Without the theological and historical dimensions, the beauty of the raw material cannot become the icon and, conversely, concepts without pictorial material lack artistic elements and produce soulless images.

Lacking this human material that can give life to the forms, icons remain pure platonic forms that we call ideas – without personal identity. In simple terms – the artist, through artistic endeavour, brings to the painting surface something of his life and experience, in order for the icon to come alive. We could rationalize this aspect of iconography by calling it personal sacrifice, but (whatever the description we use) I believe it is necessary to have authentic church art. I think for the iconographer it is important to be mindful of the borderline where conceptual and pictorial ways of thinking coexist. We must take care the two dimensions do not separate or collide as we need them together – in an unconfused and indivisible unity.

What do you think about the beholders, who will pray with your icons?

When I paint a commissioned icon, I think a lot about the commissioner, about their attitudes towards church and art, personality, taste, and a lot more. I try to construct an artistic dialogue between their position and my own, sometimes through discussion. I have to admit I’m not always satisfied with the results of this methodology and I prefer painting without commission. That is, painting icons that are exhibited and incidentally discovered by somebody who loves to pray in front of them.

I’m happy if this occurs because it brings freedom to artistic endeavour. On the other hand, I am not convinced this is the best possible method of communication between the artist and beholder, though it is helpful in what I am trying to achieve. I admit such a concept contains a bit of paying back a debt to the world of contemporary painting. With abstract painting, for example, I was not thinking of a specific but ideal beholder – usually from the future – who would understand every brushstroke I had ever made. I don’t know if there is primitive messianic reflection behind this notion or if it implies idealism incompatible with the Christian artist. The truth is, today I think about such problems in different terms. The act of painting an icon should not be primarily understood as communication between the artist and the commissioner – irrespective of how important and educated both people are. Both painter and commissioner (especially when we discuss an official commission that will become part of liturgical life) are not doing this for themselves but act as a personal prism through which ecclesiastical experience can be expressed in the artistic realm.

However important and learned the context, the icon is not a private artistic dialogue. The entire church should speak through these pictures, together with our forefathers and forerunners. If producing and using the icon is generated by someone’s private communicational needs, then why would they need to include the experience of the Middle Ages, for example? Maybe I should not speak about the ideal beholder, but instead the communal ( соборний ) beholder, who is (throughout the liturgical experience of the church) able to behold what we paint from the past, the present and the future.

The way to reflect on the popular argument concerning the aesthetics of the contemporary icon reads like this: If I can’t pray in front of it then it is not an icon . But what does that say about historic records showing us Byzantine prelates could not pray in front of Proto-Renaissance paintings on their visits to Western Europe? Should we now, after rediscovering our Medieval Byzantine heritage, destroy every icon painted in a realistic manner throughout our churches? Luckily, it is not as easy as this, and private concerns are not (or shouldn’t be) the only motivation behind decisions in church life.

What is your attitude to the following statement: Iconography is a collegial (sobornost) creative act?

The answer to this question runs through the previous one. I’d like to emphasize the concept of community ( соборное начало ) as one of the most important aspects of authorship in church art. The way we apply this concept in artistic practice is frequently misleading. It is responsible for misunderstandings about this important spiritual aspect of church art: icons can’t have several authors. Icons must not be painted on a production line, as often happens today. They cannot be treated as an industrial item – because the icon is theology in colour. Iconographers refrain from putting their signature on icons due to piety and modesty – not because icons do not have authors!

The icon includes the concept of personal responsibility because it emerges from the ecclesiastical dimension. Communitarian and personal principles are inseparable in the Church. Our Christian common deed is personal. In liturgy this means the bishop/priest is an actual person standing in front of the community in the place of Christ expressing unity through prayer directed personally to God the Father. In art it means the communion is expressing itself – its own concept of community – through an actual person – the painter/author. There isn’t an impersonal way to express the concept of community in Christian life, and if there was, I believe we would have anarchy or a kind of hippy communitarianism in church and in art. If it happens that a project is too big for one painter to execute then a company of painters must have a protomaster who makes the important artistic decisions and is responsible for the final result. The concept of personal responsibility is at the centre of the Christian concept of community and consequently, intrinsic to the life of Christian art.

How seriously is the icon regarded in the Serbian Church?

The answer to this question is easier as I am able to compare my experience of different local Orthodox Churches and regions through having been in these places and from discussion with friends and colleagues.

My answer would be in short: icons are not taken as seriously in Serbia as they are in Russia, Romania and Greece. Serbia is a small country, exhausted from wars and economic crises, so there isn’t much enthusiasm for large-scale cultural projects such as Church painting. Everybody in the Church establishment would say icons are important for our Orthodox identity, but when it comes to painting, the criteria that decides who will get commissions are low price and fast execution. Like McDonald’s – cheap and fast. I would call this between-two-wars mentality: better anything than nothing, and better now than in the future (which usually means never). This position has a positive aspect that I recognize and could exploit: art doesn’t have – let’s be frank – much influence on the life of the Church and wider community. Research implies art does not have the same influence it once had with the public and whilst this gives rise to a kind of freedom it also leaves you with a feeling of loneliness in your endeavours.

This is the reason I believe my work is better understood in Russia, Romania or Greece. It is not the question of love between us (although this would also be okay), but in those places, people respond more to artistic endeavour – and the response can be either positive or negative. Of course, there are open-minded people here who care for art, artwork and artistic endeavour, while others wait, eager to denounce you as a heretic if you do something that does not meet their code of good behaviour. But, whatever position they take, the ramifications of their reactions are not serious and as such lack the capacity to influence artistic decisions. Of course, such a position has its bad side, which doesn’t need to be discussed here. And as I’ve already said, I’m trying to exploit the positive aspects of this situation.

First off, I want to thank Olga and Todor Mitrovic for this thought provoking interview. Todor comes off as someone searching wholeheartedly for authenticity and willing to ask the difficult questions about copying, about the role of the artist, about the encyclopedic historical and technological gaze we cast today on sacred art and the effect this has on how we view what is traditional or canonical. His questions open up more than any discussion we have seen to date on OAJ about the difference between a living language of image making and a kind of nostalgic simulacrum.

His ideas have pushed my own thought further than before, but having said that, I cannot avoid serious problems I come against in the answers proposed here and the presuppositions on which those answers are based. For example, I was surprised by the comment about how it would be strange to have someone stand up and recite St-Basil, how this would be inauthentic and how this argument is used to push the idea that iconographers should innovate to find authenticity. The thing is that we do ask people to stand and recite St-Basil, they are called bishops and priests and we call it the liturgy of St-Basil. And every Orthodox person who says their daily prayers stands every day and recites the theology of St-Basil, the prayers he has written for the Church. True theology is prayer as the saying goes. This connection to the ancient saint and reciting his prayers does not prevent us from having our own more personal petitions of movements toward God, it does not prevent new hymns or prayers from entering our liturgies if they are deemed worthy to do so.

One does not need to oppose a desire to copy the ancients to the organic change taking place in iconography or liturgical practice. I agree that one needs to be careful of falling into mimetic archeological reconstructions of the past, but why does this have to be opposed by a need to actively pursue innovation for its own sake? This belief that there is inherent value in innovation is as empty and delusional as the desire to copy every brushstroke of ancient icons. Both those extremes, that is the desire to absolutely fix (.ie historical preservation societies, archives, museums, documentary photography and video) and the desire to absolutely change (.ie avant-garde art, fashion, consumer society, ADHD) are two sides of the same malaise in contemporary life. Fighting the desire to “fix” with the belief that there is some kind of absolute value in “innovation” is just swinging the pendulum to its other extreme. The satisfaction we derive from the new is not a holy one but the fruit of avant-garde utopian thinking which has strangely merged with entertainment culture. Our fascination with the new is caused by acedia and is no more a living participation in the Church than is rote repetition.

But even if there is an absolute desire to change, what change are we talking about? The statement that “on the pictorial level, the language of contemporary art shapes the way contemporary man thinks and is the only universally recognizable language we have, however imperfect” is extremely problematic. How exactly does contemporary art, that hermetic and elitist language of galleries, collectors, financial speculation and exploded visual relationships affect anyone but the very social elite of our world? And even if contemporary art would be “the only universally recognizable language”, this contemporary art has all but put aside painting since at least the 1970s, at least since Andy Warhol. And even if one takes contemporary art as a kind of image of the contemporary world, its actual “innovation” period lasted about 10-15 years tops, by 1920 there was nothing truly “innovative” being done in painting and artists today are simply repeating and commenting on what the Cubists, Surrealists and Dadaists were doing in 1916. How exactly does that matter to the churchgoer? Todor’s icons appear to us basically as Matisse and his contemporaries applied to icons, which is fine, but the self-conscious exploration of the idiosyncrasies of early 20th century modern painting (a century ago now) is no more becoming an “active Christian being-in-the-world” than copying Rublev icons from an ipad. The visual language that shapes how contemporary man thinks is not contemporary art, it is rather video, photography, advertisement, pornography, hyperlinked instant access to all archived historical images. In several comments made by Todor, he seems to be aware of this. Google and cell phones have a million times more pull on “how contemporary man thinks” than any living contemporary artist today.

The resistance I feel when reading what Todor expands upon might just be due to our different cultures. I do not live in an Orthodox Country, in fact I live on a continent who’s entire identity is based on innovation and new ways of doing things. Because of this, when I hear the argument that the Church has to have an evangelical approach by seeing what of the contemporary world it can bring into its liturgical life, it is not that I totally disagree on the principle, but my eyes glaze over slightly. This is because where I live, we are surrounded by everything from Christian Hip-Hop to Christian Death Metal. We have seen everything from Disco masses to Cabaret Christmas songs. We are drowning in sparkling empty innovation and even the Catholic Church is still hung-over from a binge of horrible modernist architecture and art on which it embarked since Vatican II. So when I, here in North America, look at Todor’s icons, I probably do not see the same thing as Russians or Greeks do.

Like I said, I think he is posing very important and profound questions and I do not want to discount what Todor is trying to do in his icons either. But especially considering his departure in Florovsky and the neopatristic synthesis, it seems to me that searching to change or “flip” the instant pictorial archive of the history of iconography (which his indeed accessible due to technology and the sophisticated modern capacity to instantaneously zap through history), searching to change a near infinite amount of quantitative data into opportunities for synthesis may be more fruitful than looking to early 20th century modernism. The capacity to surf through 2000 years of images makes it possible to see patterns emerge, similarities and meeting grounds delineated across diverse styles and geographic areas, and it is these patterns rather than either the rote copying of icons or the never ending search for innovation that can lead us into the future of iconography. This move does not ignore our historical position, and modern art can be part of this search for common ground, but the wide scope of visual access to ancient images can be used to cross centuries of accumulated divisions in the Church, while still creating a sense of the familiar in churchgoers rather than seeking to unsettle or titillate them with the shock of the new.

Jonathan,

I think you are correct in finding a different perspective in the sense that what Todor speaks of as evangelization could well seem something already overused and, indeed, dead, in the USA. Not so in Serbia; in fact, the urgency of his search for a way to bring the iconography of the Church into dialogue with contemporary expression seems to me remarkable. The anti-Church mentality is still very much something agains which pious Serbs struggle.

One point: when you mention what Todor says about St Basil, I think there is a misunderstanding. He says “We don’t need Medieval rhetoric to explain the Gospels to the people, and finally, we don’t need to recite the homilies of Saint Basil by heart. We need the opposite: if we do not bring something of our own to the communion of Christians of all ages, then we are not wholly taking part in the Sacrament. We are not actors here – but a complete and complicated people with bodies, souls, minds, knowledge and experience.” I do not at all read that as meaning that we do not need to know prayers by the Fathers, or that we should not serve the Liturgy of St Basil. It’s just an example of the way in which tradition can become sterile if it has no life.

Thank you for your Comment, Fr. Ivan. It is always good to hear from you. I purposefully shifted his discussion from the homily to the prayer because I thought it was indicative of his approach. I did it to insist that iconography is not an explicative practice as is rhetoric and homiletic but a communal and participative one in line with liturgy, architecture and music. You can see how he struggles with this aspect of iconography, how for example he prefers painting without commissions and that is also the crux behind his answer to the question about sobornost and his insistence on the unicity of authorship. I think the last question we should be asking is what we are bringing “of our own” to the communion of the saints, it is usually not the best idea to enter communion thinking we have something special to offer others. Rather we should be looking to serve Church to the best of our capacity. Aspects of our individuality will always show, aspects of our culture as well, but we should not be focused on that, we should not be actively searching to be original anymore than we should actively be searching to create technically accurate reproductions of the past.

I’m just not reading this the same way you are. I understand him to be speaking of the community as expressed through the person. He says, “The icon includes the concept of personal responsibility because it emerges from the ecclesiastical dimension. Communitarian and personal principles are inseparable in the Church. Our Christian common deed is personal. In liturgy this means the bishop/priest is an actual person standing in front of the community in the place of Christ expressing unity through prayer directed personally to God the Father. In art it means the communion is expressing itself – its own concept of community – through an actual person – the painter/author. There isn’t an impersonal way to express the concept of community in Christian life, and if there was, I believe we would have anarchy or a kind of hippy communitarianism in church and in art”, and I understand his work to be conceived in that spirit, which does not seem to me at all to be exalting the personal *above* serving the Church; on the contrary, he would be denying his own God-given talents if he did not contribute what only he can.

Johnathan,

I’m sorry to join the discussion so late, but as an illustrator myself I can relate to Todor’s view. I understand and agree with your concern for individualism and how it can be problematic for one’s soul even to focus on “bringing something new” to the table. That being said, where would we be if young Athanasius decided that at 24 years old he has nothing to add to our church theology and opted not to write “On the Incarnation”? I know, a bit of an extreme example.

I remember asking our local priest why we don’t rewrite theology in modern terms, and he just sent me an article called “Strip the vanity of the heretics”. This attitude might be the safest, but it’s really not going to help the new generations when our arts, hymns and stories are are told in a language they don’t understand or relate to.

This isn’t about the artist, when I illustrate a picture it’s never so I can sign it and call it mine – then leave my mark on orthodox history forever! That’s not why we paint. Art is to me a dialogue with God, and a partaking in His creativity. This is more about the Spirit speaking through the ages in contemporary languages the people would understand and less about the artist themselves.

That’s what I think anyways 🙂

Looking at these icons is like trying to remove your eyes with a cheese grater.

Dear Jonathan,

I think there are always bad examples of how to modify the text of the liturgy or how to celebrate it really badly without modifying it.

It’s not a secret, that all creative researches are based on experiments, which may seem very odd sometimes, but they are the only way to go forward.

And for Paul, – I sincerely regret if these images hurt your senses. I suspect I feel the same when see someone painting an icon of the Mother of God looking nice and lovely.

I have seen his work before and I am grateful for the interview and to learn more about his process. I think relating Icons to contemporary art is a courageous thing to accomplish, drawing fire from both camps. However, Mitrovic’s Icons are great examples of art that can also speak to the contemporary art world and God knows, Icons are needed there! Bravo, and thank you, Orthodox Arts Journal for publishing an artist’s work even if it is not fully to your taste. With God’s help we will all be able to make Icons that bring Him to a world that is in great need of Him.

Thank you very, very much for this interview! I am so happy to see this next step after the book I have read last year! It is really very nice to have something so profound theoretically and practically useful – also available to English-speaking iconographers! And let us hope this interview will help removing timbers from many eyes – even without any grater 🙂 What I look forward is more complete reportage from church with mural-paintings by Todor Mitrovich that appeared on the Internet only partially – when it will be completed. Besides numerous very good points and argumentation in his work, d-r Mitrovich is remarkable with the fact that he does not provide model for copying and does not suppose one would start copying his style. This humble attitude allows him to be free to set his icons free to speak and preach, after long years of silence in museums, galleries, souvenir shops, repositories, etc. What I also expect is the voice of the huge and talented groups of Russian and Romanian iconographers who already appreciate and develop ideas of professors Skliris and Kordis without copying their style and works, but by creating new, sound and authentic icon-painting traditions recently.

Hello to all!

For the beginning, I am very grateful to editorial board of OAJ for decision to publish this interview and, more specifically, to Olga, Philip and Jennifer, for making it happen.

Since this dialog was not made as an attempt to produce some kind of undisputable manifesto or artistic credo, but was imagined – at least from my point of view – as an invitation to wider discussion about questions raised, I’m happy that, at the very beginning of its public life (in English language), this discussion is already opened. This is why I’m also grateful for all the comments – however critical some of those might have been. Moreover, I consider the augmented and constructive critics only as a huge help if we want to be closer to truth and improve what we do in that direction. From this point of view, I’d like to expand discussion on questions raised in comment of Jonathan Pageau – maybe as a set of additional notes to original discussion with Olga and Philip.

* Let’s begin with the comment connected to Saint Basil the Great. Experience tells me that our contemporary analytic mind is capable to deconstruct every possible positive statement given in written form. So if I’d try to answer the argument of St. Basil comment in this (analytic) manner, than I could simply admit the mistake and say: let’s improve my metaphoric comparison by switching the writings of St. Basil with those of St. Gregory the Theologian, or St. Maximos Confessor, who haven’t been writing the text of liturgy but are also a real cornerstones of the teaching of the Church. On the other hand, the strict differentiation of homiletics and liturgy would not be so easy to establish, neither from theological nor from historic point of view. For example, homilies of St. Gregory the Theologian directly influenced formation of famous Easter Canon of St. John the Damascene, which, later on, became inseparable part of Easter Vigil – one of the most important services in contemporary Church life. Finally, icons are not used only in liturgy, and could also have explicatory functions – in liturgy or out of it. And so on… But I am not writing this comment in order to practice the skill of deconstruction, and I think this kind of answers is not sufficient and not important, at all. I do recognize a really positive intention and enthusiasm behind Jonathan’s comments and that is what I’d like to discuss. The truth is that we really do learn some texts by hart in our Church life. Together with few important prayers, we should know the Creed, which is – as we all know – a short theological statement, formulated on first two Ecumenical Councils, as a minimum of common teaching (dogmata) of the Church that cannot be disputed (this is, of course, why the text of Creed could became one of crucial reasons for later dispute with Roman-Catholics). Attending the liturgy, we also learn its text by hart, because it is also something that brings us together in front of Gods face, and – though liturgy itself has changed a lot from the time it was written – we are not fond of any kind of interventions in this text. But, in library of school where I tech we have the complete series of Patrologia Graeca and it looks so huge, on shelves, that even its reading looks like lifetime effort to me. This enormous ‘spiritual data bank’ also contains the teaching of the Church, and it is an important part of its heritage/tradition. But, how can somebody who has not spent lifetime on reading it, take part in this important aspect of Church tradition? Let’s turn again to father George Florovsky ,who truly dedicated his life to interpreting this heritage, for more detailed opinion. “The Fathers were true inspirers of the Councils, while being present and in absentia, and also often after they have gone to Eternal Rest. For that reason, and in this sense, the Councils used to emphasize that they were ‘following the Holy Fathers’ – επόμενοι τοις άγίοις ιτατράσιν, as Chalcedon has said. Secondly, it was precisely the consensus partum which was authoritative and binding, and not their private opinions or views, although even they should not be hastily dismissed. Again, this consensus was much more than just an empirical agreement of individuals. The true and authentic consensus was that which reflected the mind of the Catholic and Universal Church – τό έκκλησιαστικόν φρόνημα. It was that kind of consensus to which St. Irenaeus was referring when he contended that neither a special ‘ability’, nor a ‘deficiency’ in speech of individual leaders in the Churches could affect the identity of their witness, since the ‘power of tradition’ – virtus traditionis – was always and everywhere the same (adv. haeres. I. 10.2). The preaching of the Church is always identical: constans et aequaliter perseverans (ibid., III. 24.1). The true consensus is that which manifests and discloses this perennial identity of the Church’s faith – aequaliter perseverans” (The Collected Works of Georges Florovsky, Volume 1, Belmont, MA 1972, 103).

So, about some subjects – written in Creed, for example – there is no need to dispute, and this is why we usually learn those contents by hart, but it seems that more than few questions are far from being solved yet. How all this discussion could be (in turning back from the metaphorical realms) structurally related with the Church art. Well, we should expect that there are, similarly, some aspects of Church art that should not be disputed through our artistic researches. Some kind of credo we all do agree about. But the problem is that art itself was never subject to verbal definitions, and the only place where we can find this kind of credo, this common teaching of the Church – the “power of tradition” which is independent of any special “ability,” or a “deficiency” of its actual witnesses – is the surface of (medieval) icons. Since the Byzantine art has passed through extreme formal changes through its millennial history, this is not an easy task, at all. Should we search in 15th century, or 14th, or 13th, or 12th, or 11th, or 10th…? And where (?) – in Constantinople, or Crete, or Thessalonica, or Cyprus, or Serbia, or Russia…? Which one is the most Byzantine among these virtually very different historical incarnations of Byzantine artistic spirit? In my opinion those are the wrong questions. I’d rather say that the common grounds – or, what we should learn ‘by hart’ – can be only the artistic content, or the artistic behavior, that is common for all of those great centuries (periods) of Byzantine art. In my opinion, the epicenter of such a credo should be posited in the very face of the saint. Its recognition. There are, of course, some other aspects of this art that are historically very stable, so could be also extracted to this hypothetical pictorial credo. But opening of such a delicate discussion would be too much for this comment. I’d like to call upon the groundbreaking researches of George Kordis, who analyzed those problems with highest precision. It can be found in his different publications and, also, in his interview in OAJ. So, I’ll end this additional note with suggestion to everyone interested in discussion on subjects opened in here to consult his extremely inspiring interview.

* The other subject I’d like to discuss can be posited in space marked by two key terms: contemporary art and innovation. I was using the phrase contemporary art in most general sense of the word(s), in order to avoid modernism-postmodernism discussions, but it seems inescapable somehow. The concept of novelty – at least the way it was promoted by avant-garde movements (from the first decades of XX century) – is outdated long, long time ago in “contemporary” art. Being one of most profound initiators of this process (later on designated by term postmodernism), Warhol paradoxically saved the art of painting – almost self-denied through lyrical abstraction or art informel – which would be otherwise murdered by ‘new’ media. Finally, art was dying and resurrected several times in XX century and painting itself was passing through this comic scenario even more frequently. Reading of this scenarios today really looks like a kind of bizarre joke – though it’s not correct to laugh, because people spent their energy, their lives (and some of them even earned a huge money) playing this game. So, expecting any kind of radical novelty in any kind of art today is, at least… well, not necessary. This is why I have not used term ‘innovation’ (or its derivates) at all – not even once. To “belief that there is inherent value in innovation” (!?) – c’mon, I believed this centuries ago, while I was in primary and secondary school. On the other hand, in Jonathan’s comment the word ‘innovation’ (and its derivates) was used 9 times. Does this tell me that we misunderstood each other? Luckily, word-count is not the key argument in this case. The question is actually very important, uncovering the most subtle dilemmas of my work, for which I have not found disambiguate answers yet. Truth is that there is a kind of need for innovation behind my work. But it is not unconscious, at all, and this is why it – as Jonathan rightly observed – should be discussed in its (cultural) context.

The religious kitsch is a phenomenon that cannot be escaped in any geographic and cultural space. The Christian Hip-Hop and Christian Death Metal might be inventions of American popular religious culture, but the soulless icons are inventions of orthodox popular religious culture. I don’t know which ‘invention’ is the worst, but I know that myriads of those soulless images are the reason nobody (serious enough and educated enough) considers that icons are art, in here. Every serious artist or art historian will agree that medieval icons/frescoes/mosaics are huge art, but nobody will consider even a possibility that contemporary icons/frescoes/mosaics could be art. And this was hurting me, not as an artist (I could always turn back to my abstractions), but as a Christian. It was hurting because I recognized elements of socialist and liberalistic ideologies behind such an attitude (as well), but it was hurting more because – with or without ideology – it was/is truth! Is it possible that Christians are not capable of making powerful art anymore? Is it possible that we became so self-sufficient that we don’t care if somebody from outside of our community tells us we are making a real kitsch? Try to imagine you’re the conductor of church quire; the professor of conducting from Moscow Conservatorium comes to church and tells you that you are totally out of the rhythm and the harmony; he leaves, but you say to your singers and to yourself: who cares – he don’t know what he is saying, because he is not in Church… This is the way we behave (!) but I’m not sure this is the way Byzantine or early Christian artists would behave if they were in our place. Holy fathers where holy because of the Holy Spirit, but if they were theologians they could be enormously educated. And we cannot even read their treatises without solid knowledge of Plato and Aristotle. The language of key theologians of Church was, very often, based on Plato and Aristotle. Why Bible was not enough for them, but they needed Plato and Aristotle? Because that was the only way to approach the Roman and Hellenic cultural space! Actually, that was the only way to approach Roman and Hellenic intellectuals. And those intellectuals are – as always and everywhere – people who are modeling the cultural horizon of the epoch. Christian theologians (and artists as well) were not ignorant to this cultural horizon, but carefully listening and trying to understand it. And this is the way ancient theologians succeeded in unbelievable and even miraculous enterprise: they molded Greco-Roman culture according to Biblical law by using Plato and Aristotle. Somebody might say this looks like a kind of trick, but I would say this is the only way it could be done and it was done with the wisdom that is a true God’s gift to the world.

So finally, I wanted to rely on this kind of role model when started reasoning about artistic behavior in contemporary situation. Someone will say: ok, why not, but, what all of this has to do with the concept of innovation? According to described, my intention was to connect the two very distant cultural poles: Church and highest academic authorities in visual arts. With completely opposite reasons, both ‘camps’ – with more or less passion – paradoxically agreed about proposition that icons are not art. This paradoxical agreement is induced by (already described) ocean of ecclesiastical kitsch, which was/is covering the horizon between the two groups of beholders my art was addressed. And my goal was simple: if both camps admit that contemporary icons can and should be art, then we have platform for communication that was previously disabled. Based on described ancient experiences, my opinion was that this kind of dialog is very, very important for both – the Church and the world. But, finally, if you want to address the two distanced ‘camps’ – safely withdrawn in the shells of their (distanced) attitudes and prejudices – and you are swimming in the ocean of kitsch, then sometimes you have to speak very loud and very sharp. My need for innovation came from such a position. In order to be at least visible in such a context, my icons needed to speak loud about the artistic aspect of icon. And, to be honest, more than once I felt that I’m going too far with this, because my attitude about art is actually opposite. I don’t think innovation is important at all. Actually, it is important – as any other artistic means – but it is not the key aspect of artistic endeavor. I don’t have problem to recognize the art, and even novelty, in icons that are done in very traditional manner. What makes icon new and authentic is not experiment but the energy and love involved in its painting. This is my general attitude which was attested through 1.5 decade of pedagogic experience. (I teach students to copy medieval icons, if somebody was concerned about my pedagogic influence on Church art in Serbia; only medieval – not contemporary; nobody is forced to be innovative and I do not expect them to be informed about the way I paint icons, at all). Finally, I can never be sure that my loud researches are better than those quiet ones. But I do think that sometimes it is important to speak loud and sharp. My opinion is that contemporary Church (art) needs different kind of voices in its quire – loud and quite, sharp and gentle, rough and delicate… In between those voices, the melody of the ‘virtus traditionis’ will became alive and really authentic. Maybe we could call this the principle of ‘sobornost’ in the context of our discussion.

* Finally – one short appendix to all that was said. What I’m especially interested in domain of artistic expression, from strictly aesthetic point of view, is the color. This is the only reason I was relying much on Matisse, as it was rightly observed in Jonathan’s comment. I don’t think of this artist as an innovator (at all) but as one among great teachers of color. The use of contemporary palette of pigments is simply defined by artists of this kind. It is simply naïve to think of using those colors if you have not experienced what Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse, Rothko… for example, have been doing with them in past. I’m not thinking about Matisse in essentially different way I think about Vermeer, Velazquez, Rembrandt or Rubens, for example. (I have no doubt those artists also can teach us a lot, even when art of icon is concerned, only if we can read their art carefully.) So, to make one small correction, when I said that contemporary art is defining our visual horizon, I was having in mind all art of 20th and 21st century. Together with the art(s) of design, of course, which often do offer much more artistic content than dreary intellectualizing from autistic gallery life. I agree that our visual horizon is defined by innumerable screens – from cell phones to billboards – that are surrounding us, but my point was going this way: try to imagine how all of those toys would look like if there was no Donald Judd or Frank Stella, for example. Try to imagine how the Google front page would look like without Matisse. I don’t think it would be the same. Even if we didn’t like this kind of development, it seems that it has happened, and I think we should use its good sides. Early Christians probably did agree with Saint John’s apocalyptic metaphors, describing Rome as “the great whore” (Rev 17-19), but did not avoid to rely on roman communication network in their preaching. Moreover, early Christians embraced roman art in spite the authority of Holy Scripture was not supporting art at all. At the end, Roman Empire became Christian Empire and produced art that is unparalleled in history for its spirituality and its beauty. Of course, we are not living in the times of early Church, and I don’t think we should be so naive to apply those lectures from history literally, but I also do not think we should avoid taking them into account only because their origin is not medieval. Every lecture from history is important, as well as it is important to discuss the way of its potential application in contemporary context.

Todor, I really want to thank you personally for your time doing the interview with Olga and in pursuing the debate. Your interview has been viewed thousands of times and so the questions you raise in your answers are of real concern to many. Also, as one of the editors, I am of those who worked on getting the interview up in the first place. So despite having formulated the strongest objection to your ideas, I have also stated that I admire your capacity to pose the right questions with energy and honesty. Also, there are some of your icons that I find quite touching, especially those of St-Paul which have almost a Japanese print feel to them.

As an editorial decision for OAJ, we do not to let discussion run interminably into the comment section, so I will not answer what you have written in detail. But in brief, although my first comments still stand, I think that your additional statements definitely help us to understand your position better and they continue to show us that you are taking these issues very seriously and posing the difficult questions which many iconographers would not dare ask.

So thank you again, and I sincerely hope that our paths will cross one day. Your brother in Christ. Jonathan