Similar Posts

Editor’s Note: Following upon Aidan Hart’s recent post about applications currently being accepted for the 3-year Icon Painting Programme taught by him, we present an interview with a 2019 graduate of that program, Baker Galloway, conducted by Seraphim O’Keefe on behalf of the OAJ.

Introduction

Baker Galloway is an American graduate of the 3-year Icon Painting Course offered by the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts (London, UK). The course is taught in Shrewsbury, UK by Aidan Hart, who has contributed prolifically to the field of iconography (writing, teaching, painting, carving, mosaics, liturgical furnishings) over the past 30+ years in the UK and internationally. Baker participated in the 2016-2019 course with ten fellow students, graduating in October 2019.

Baker is a dear friend, and I am excited about the work he is doing. For years, he and I have shared our experiences and ideas about art and life. In March of 2019, he invited me along on one of his trips to England, to meet Aidan and to see the iconography class in action. My encounter left a profound impression on me, and now it is a privilege for me to introduce Baker to you, and to share his story.

Seraphim: Baker, before we go into detail about your experience studying in England, let us know a bit about your background, your education and your involvement in the arts.

Baker: Hi Seraphim, thanks so much for this opportunity to talk about myself and my art. (Two of my favorite subjects!) Hmm, let’s see. I was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, and grew up in Boston, Massachusetts. In the middle of my teenage years my family moved to Austin, Texas, where I still live now.

From childhood I always got a lot of satisfaction from drawing and sometimes sharing my drawings with others. As an emotionally repressed introvert I suppose it was a safe way to put my emotions out there in public and invite a connection with other people. I have never been much of a doodler, but rather see visual art as a medium of communication between persons. In my process, a seed of an idea is conceived first, and then I work to give it life by expressing it as best I can. I dabbled in philosophy and fiction writing when I attended the University of Texas at Austin, and eventually majored in Radio, TV & Film. But by the time I graduated, I had found myself ill-suited to these vocations. I did take one art class before graduating from UT, and stumbled into a creative voice of my own as a painter. I exercised this newly-realized, unexpected gift of my creative voice in delight for about 8 years.

During that time I painted people in a cartoon-like simplified style. Usually I worked on large scale paintings that had a formal simplicity which belied their psychological complexity. I loved to explore themes of shame, fear, delight, simple-heartedness, and struggle. I think the motivation behind this phase of my work as an artist was to put the spotlight on vulnerability. In doing so, I invited the viewer into a moment in which my humanity and theirs was cherished.

Happy Birthday (2005), acrylic on canvas, 72″ x 36″

This period of my life coincided with several other seasons: the beginnings of my career working part-time in architecture, also my exploration of whether I might become a monastic, and then the early years of my marriage. I had found a creative voice and discovered that I had things I needed to say (visually), and it was a great joy to deliver these paintings into the world. I am tempted to look back on that as a golden time, though I know it was actually full of insecurity, dysfunction, and immaturity. I don’t really wish to go back in time.

In any case, my artistic inspiration eventually dried up in a significant way, combined with life circumstances that also limited the possibilities of producing much art. This closing of the door on contemporary art coincided with meeting the exceptional iconographer Vladimir Grygorenko, who had been a student of Fr. Zenon Teodor before moving from Ukraine to Dallas, Texas. Vladimir was very gracious to me and gave me my foundational instruction in iconography at his studio in Dallas. With him I began learning composition, anatomy drawing, drapery in iconography, how to work with pigments and egg tempera paint, and how to make icon boards. I will always be indebted to Vladimir for this training he generously shared with me, which spanned about two years’ time.

In 2011 my ex-wife and I welcomed our son into the world; and for a couple years I did no painting at all, but occasionally late at night made icon drawings with crayons, colored pencils, or conté crayons. In 2013 I had the great opportunity to attend a 5-day icon painting course taught by Aidan Hart in Shropshire, UK, and afterwards visit the Monastery of St. John the Baptist in Essex. During this trip I was given a sufficient view of the work that remained ahead of me (in my training) to decide that iconography was indeed a vocation I wished to pour myself into. Up to this point I still suffered from a great deal of angst and indecision.

My angst was in part due to the sacred calling of the icon: that one must not rush into it with an agenda or ambition. Iconography is like a sacrament for the eyes, and to be good iconographers we must be humble servants. I struggled with this because I felt very much that I had a lot to say, and I quite liked my own creative voice. I did not know whether I could relinquish control of my artistic life to the Church.

Thankfully, during this season I passed through the canyon of doubts and came out into the valley of hope. Working in correspondence with Aidan over the next several years I completed a few icons. In 2016 I applied to the Icon Painting Course at the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts, which is a three-year course taught by Aidan. The notion of undertaking such training was supported and made possible by my family and community. My application interview took place just hours after the birth of my youngest daughter, after which I was accepted into the program, which began in October 2016.

Icon Painting Course students at work in our classroom at the Trinity Centre, Meole Brace, Shropshire

Seraphim: Was the 5-day course with Aidan the turning point for your doubts? Could you describe Aidan’s character as a teacher?

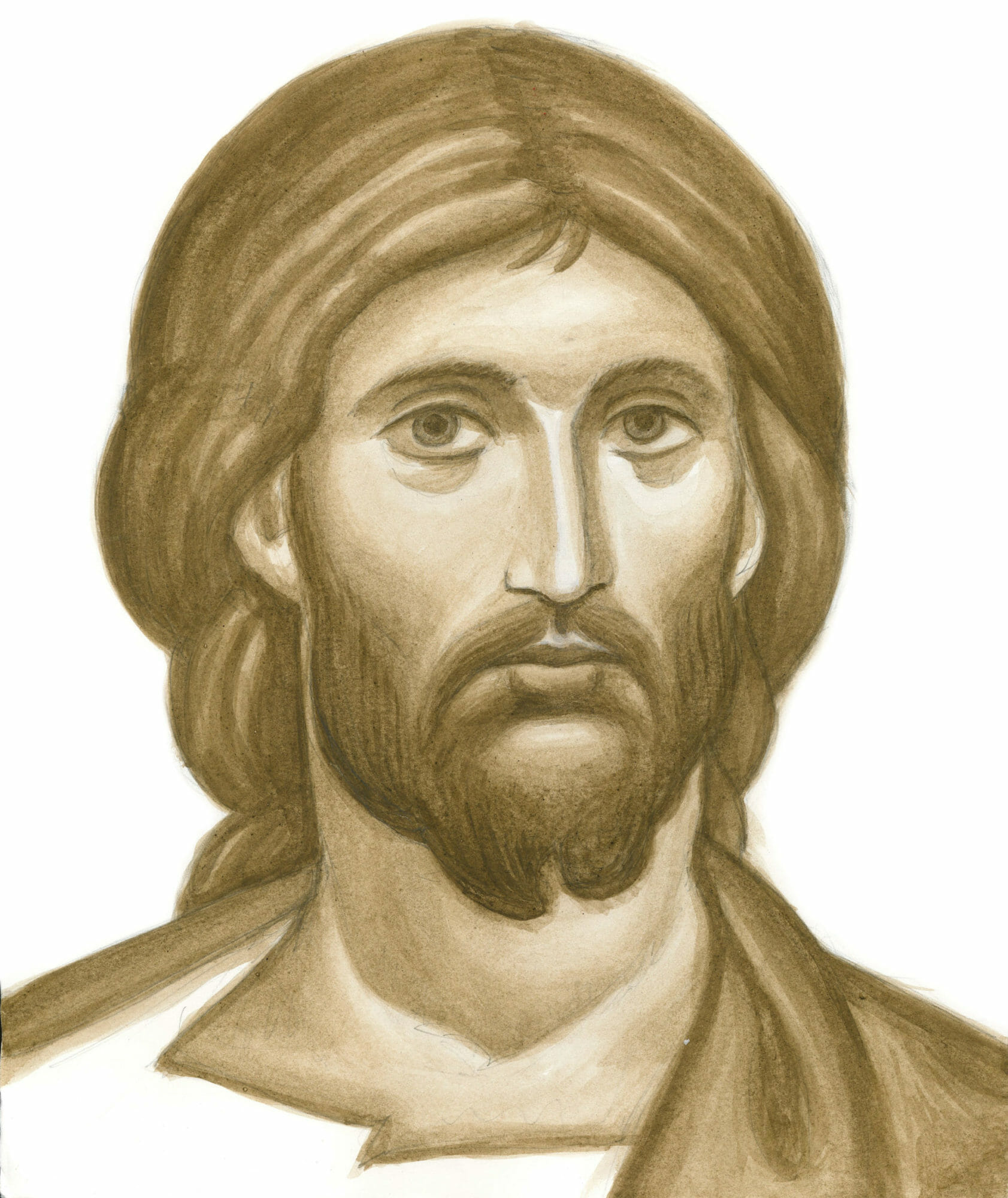

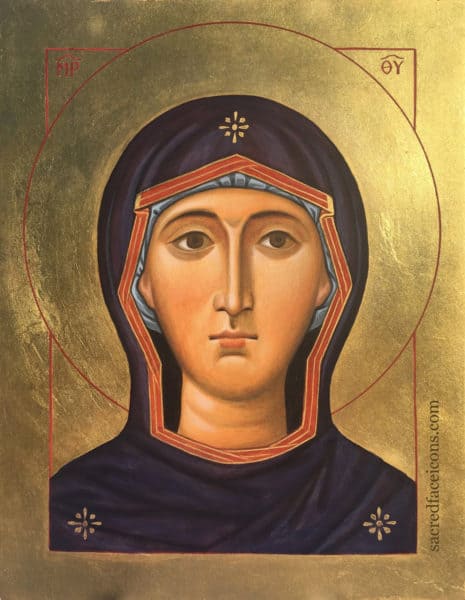

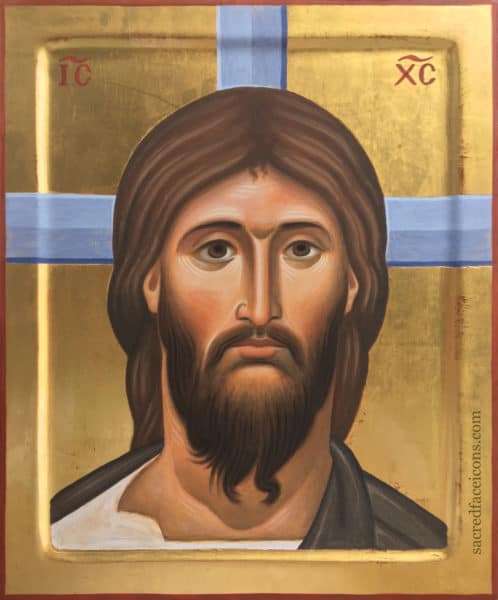

Baker: On your first question, it’s hard to say, but probably so. I was so worked up in confusion and doubt that I had an internal knot that had to be kneaded out, so to speak. The clearest way I can communicate my central crisis about becoming an iconographer is that I feared being inadequate to the task of painting the face of the God-man Jesus Christ. My concept of the iconographer had been one of a passive transmitter who must obliterate their personality and individuality in order to faithfully portray the Truth. In my mind, there was on one side the risk of failure, and on the other side the loss of my identity. Failure looked like falling short of making acceptable icons of the True One (thus as an artist, ultimate vocational failure). Loss of identity looked like the possibility of success in making acceptable icons, but at the cost of my own creative voice and individuality. In other words, so much of who I knew myself to be would have to die in order to make an acceptable icon, that nothing would be left of the me that I liked.

In getting out of this funk it’s hard to say what was most instrumental – the prayers and support of people who love me, the pushing of my priest, the time needed to suffer and mature, the experience of working at it, or the teaching and encouragement of Aidan and others. Surely all these forces are manifestations of God’s loving providence. But yes, beginning when I met Aidan on that trip, and in my conversations with him over the next three months, he gave me the encouragement and validation I personally needed to believe that iconography was something I could do. Perhaps some souls aren’t in need of others’ validation to move forward in their life, but it’s been quite a theme for me.

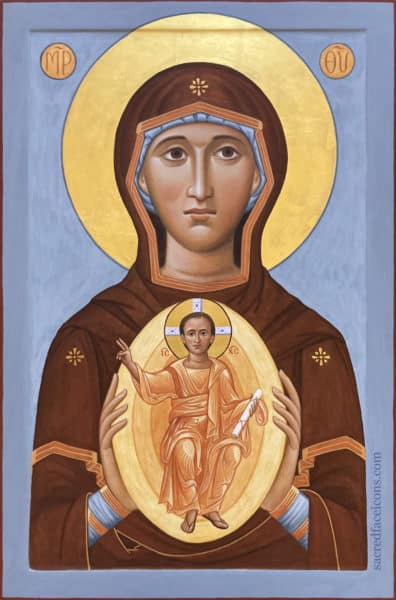

There was also a thought of the heart that came to me when I visited the monastery of St. John the Baptist in the days after my initial 5-day course with Aidan. This spiritual community has provided me with significant guidance at several key milestones in my life. On this occasion the thought that struck me was this: the work of depicting the face of God is not best considered as a height of inaccessible artistic perfection (that one strives towards, always failing to properly connect). Rather, it is an invitation. When Andrei Rublev painted the face of Christ, when Fr. Gregory Krug did so, it was Jesus Christ himself who wished to show his own face to those iconographers, through their own hands. The calling to manifest His Face in icons was something the Lord wished to bless his iconographers with first and foremost. Before anyone else would see these faces of Christ, the iconographer would get to see them wonderfully arise in the medium in front of their own eyes, by their own hands. And with this thought came the sense that I was being invited to that same joy. This is the thought that dissolved the stubbornest bonds of my internal conundrum.

Now, to answer your question about Aidan’s character as a teacher, I would be most delighted. I believe Aidan is currently the best teacher of iconography that one can seek out in the English-speaking world. He is thorough, patient, cheerful, and erudite. He is also very kind. Aidan is the sort of teacher that conveys to all what is most important in a subject, and then cultivates each student according to his/her own gifts and natural inclinations. His aim is to raise the bar of excellence in iconography as high as possible. He is a practicalist, not a perfectionist. His curriculum devotes roughly equal time to theory and to practice. His taste in iconography is eclectic, appreciating many diverse schools within the Tradition. Actually, Aidan is a great lover of many secular arts as well. He directs his students by example to live as the honey bees that gather pollen from all manner of flowers, storing up and making spiritual honey in our hearts. He teaches that we must immerse ourselves in the life of the Church, and that as we learn to hear the music of heaven in our soul, this will guide us as we step forward in the creative work of making icons. Aidan is bold in his exploration of the best ways to express the gospel through iconography, not shying away from new compositions. He forbids his students to trace the prototypes we study, but to always make a fresh drawing of our own. He is passionate in his love of the liturgical arts, but also seems to know his own limitations. Aidan has taught iconography in a formal setting for a number of years now, and has developed an excellent curriculum that he leads his 3-year students through, which I hope can be emulated elsewhere. These few words I can say about my beloved teacher.

Seraphim: Thank you, Baker, this will be a treat for people to read. That moment of contact you describe, watching the face of Christ, and of His Mother and all the holy people, come to light in quite unexpected ways, for the sake of the people of God who will see it – is the most fulfilling experience for an iconographer! Please, sketch for us the basic shape of Aidan’s curriculum for 3-year students.

Baker: Yes, I was surprised to discover that no amount of external recognition or validation from other people for my work as an artist is nearly as satisfying as guiding a holy person’s face into the world on an icon. That’s something I try to remind myself when I get hungry for words of praise.

Now yes, I’d be glad to outline the three years of study under Aidan during the Icon Painting Course. I’ll summarize below from memory. Before going on I’d like to make the distinction that this course I participated in with Aidan Hart is distinct from the MA, MPhil, and PhD degrees offered by the Prince’ Foundation School of Traditional Arts. I don’t know much about those other programs, but I believe some students in them have focused on iconography. However, Aidan is not associated with any of those programs as far as I know. Here is what Aidan’s Icon Painting Course curriculum looks like:

Year One

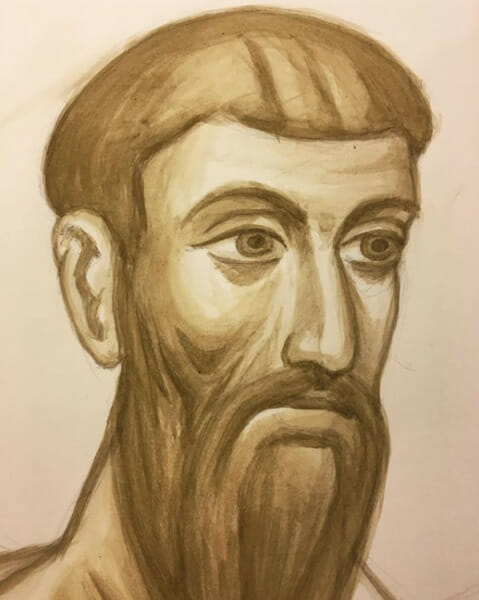

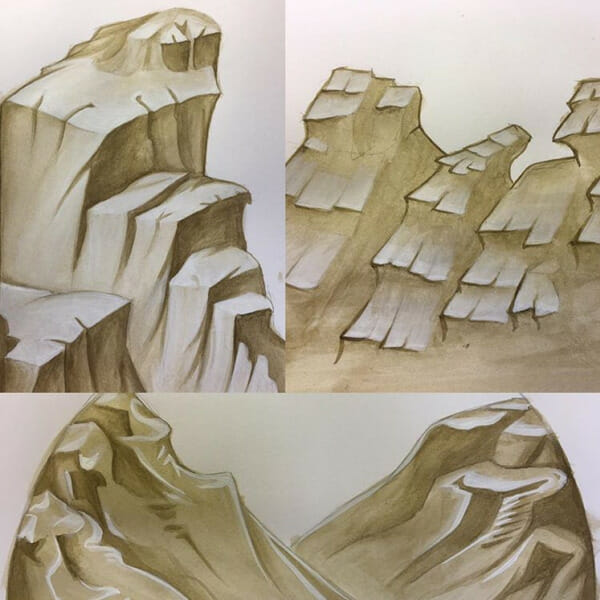

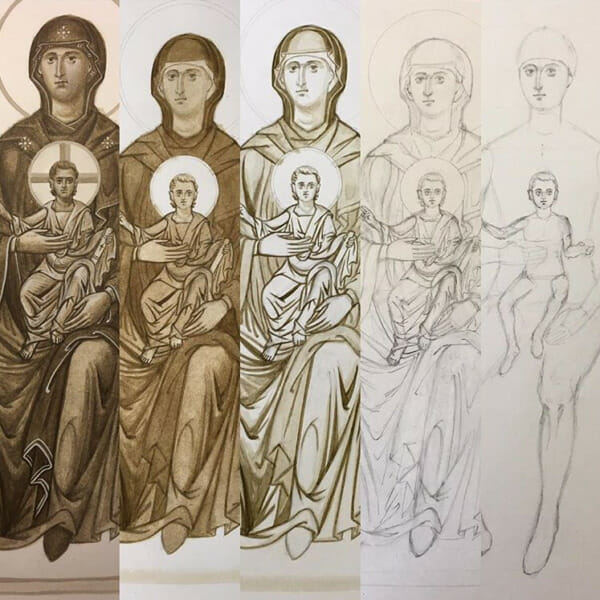

The first year of study is spent drawing and gaining familiarity with the materials. We paint no finished icons during this first year, nor do we do anything in color; only monochrome. In the first year, as in all following years, Aidan presents us with a massive portfolio of curated icon prototypes to emulate, all of excellent quality. This is done so that each student may select and dedicate themselves to works they are naturally drawn to. It helps to go with inspiration when learning a new set of skills.

As far as subject material, we cover:

- Review basic principles of drawing

- Anatomy studies, with special attention on the head, hands, and feet first of all; then half-length figures; and finally, full-height figures, and more complex compositions.

- Mountains, Trees, and Plant life studies

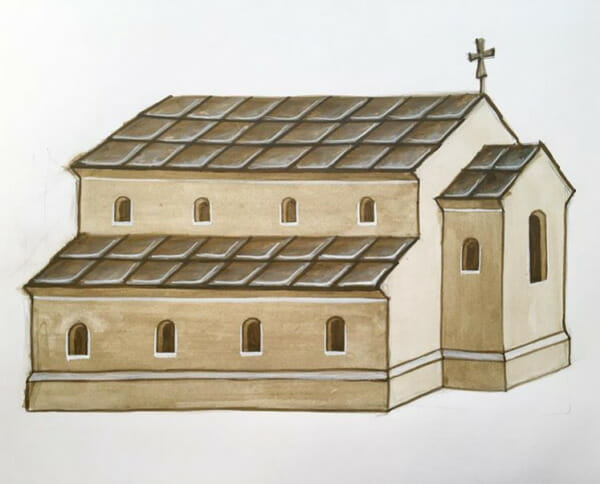

- Garments, Drapery, and Architecture studies

As far as materials, our practical orientation includes:

- Painting on watercolor paper

- How to make and use egg tempera paint with natural pigments

- the value and use of different kinds of brushes

- Making traditional gesso and icon boards

- Gilding techniques (oil- and water-based)

We finish the first year with a large quantity of works on paper: all monochrome egg tempera paintings, made using a single pigment (usually raw umber) with egg yolk emulsion. These studies are extremely valuable and much less expensive to practice than full finished icons. The sentiment among my classmates at the conclusion of the first year was that we all wished we could have another whole year of working in monochrome on paper. But alas, it was time to journey onward.

Year Two

In the second year we begin making full-color, gilded icons on traditional icon boards. We also study color in great depth: different properties of various pigments, their preparation and use. We study color theory and color symbolism. We also learn the two basic methods of building up form using translucent layers of paint: the ‘membrane’ technique, and the ‘proplasmos’ technique. We practice lettering, gold assist lines, and the various finished details of how best to make a painted icon. At the end of the second year we have completed:

- Two bust icons (face and neck)

- Two half-figure icons (waist-up)

Also during the second year we each begin a thesis paper about an iconography-related subject of our choice.

Year Three

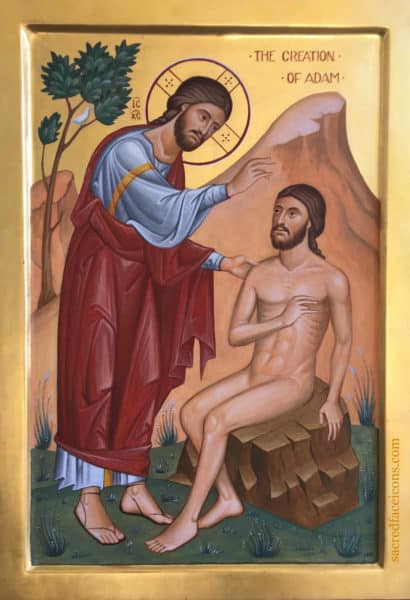

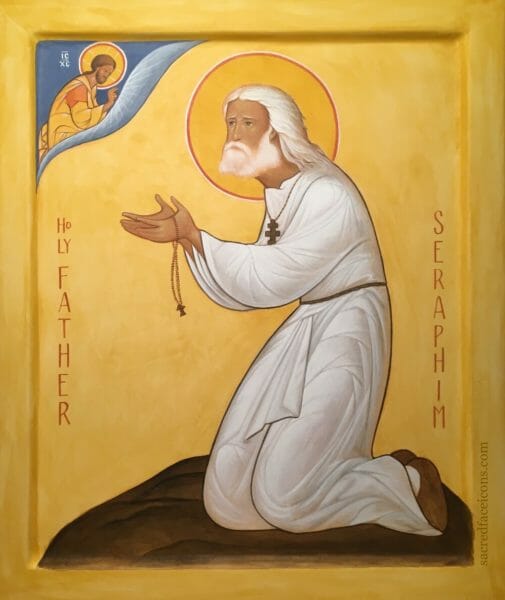

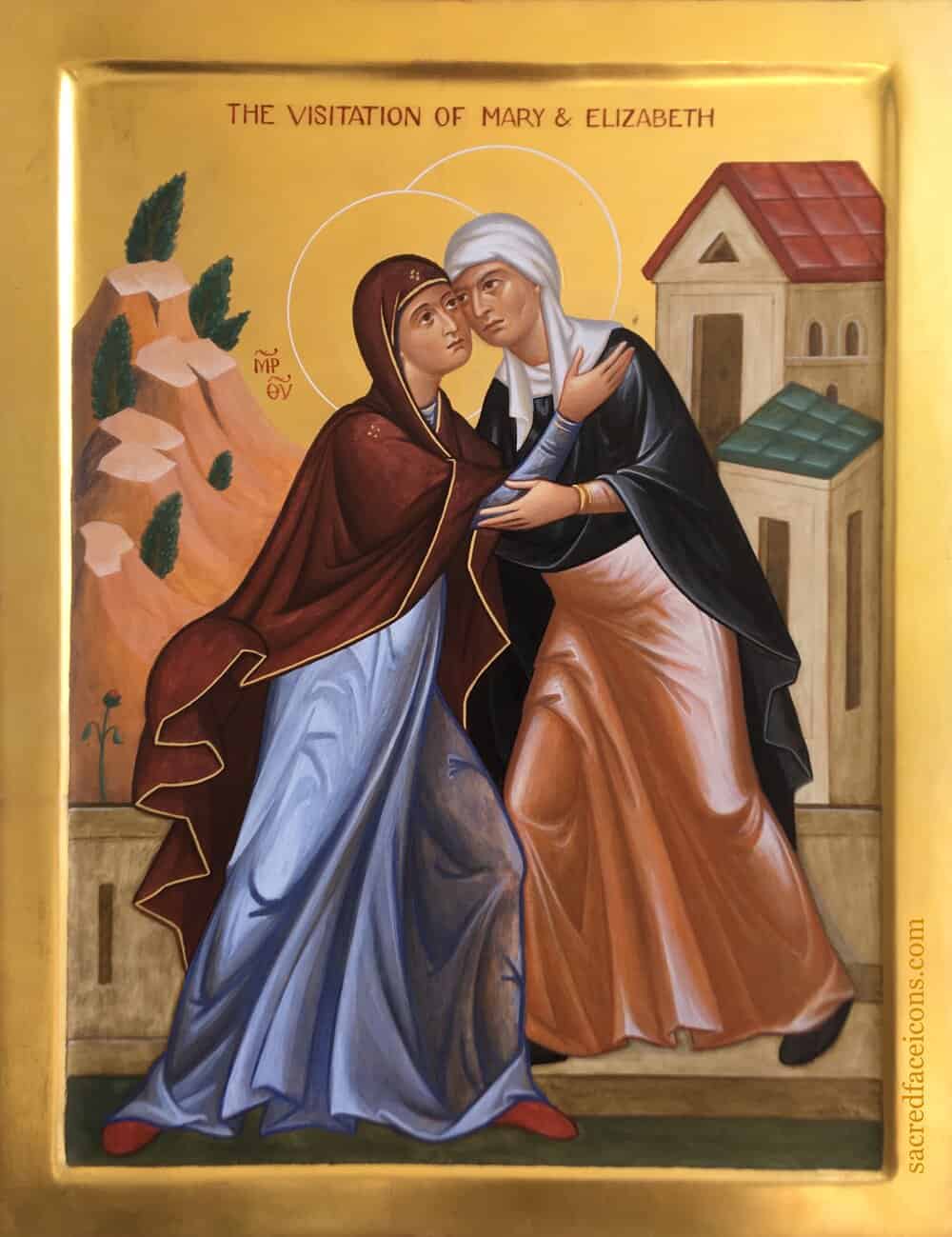

During the third year we build and expand upon the knowledge and skills we have already acquired, gradually adding greater complexity. We paint two standing/sitting full-figure icons on larger boards, and we compose and execute a festal icon as our final work (multiple figures in a scene). At this stage Aidan forbids us to strictly copy any one precedent icon, but insists we draw inspiration from several prototypes, so that under his guidance we make the transition from copyists to artists capable of interpreting and contributing to the Tradition. In the third year some students also have opportunities to attempt other media, such as silicate paint on plaster, or manuscript illumination on vellum. During this third year we also turn in our thesis paper.

The third and final year culminates in a graduation exhibition of the students’ best work at the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London.

2019 Graduates pictured at our final exhibition opening (from left): Claire Barrie, Baker Galloway, Victoria Tomlinson, Elena Kosmopolou, Michelle Hazell, Hristina Ivanova, Margaret O’Shea, Silvia Cavazzuti-Evans, Annette Ashton, and Christina Watson. Also, but not pictured: Lisa Abbott

Other Curriculum Notes

Logistics:

- When our class gathered to meet for a session, it was always for three consecutive days at a time, Monday through Wednesday. We met in a classroom at The Trinity Centre, Meole Brace. Shrewsbury is a beautiful historic town, and a real treat to visit.

- We met like this seven times a year for three years.

- We ate lunch and dinner together each class day, and shared morning and afternoon tea breaks.

- We prayed together at the beginning of every day, and before meals.

- We took field trips to visit Aidan’s studio, and the workshop of Dylan Hartley. We also visited the Orthodox parish in Shrewsbury twice.

- We had guest lectures and demonstrations from Martin Earle (mosaic), Seraphim O’Keefe (silicate painting on plaster), and a Brother of the Shropshire Monastery (website design).

- Our third year included a one-week field trip to visit the historic churches of Thessaloniki, Greece.

- Outside of class we had approximately 8 hours of hands-on homework to complete each week.

Lectures:

Nearly every day of class, Aidan began with a 90-minute lecture. He covered a wide breadth of topics. Some that I recall were: Orthodox Christian theology, prayer and devotion, hymnography, history of the Church, history and influences of various iconographic ‘schools’, various liturgical arts and media, the relative value of contemporary arts, color theory, composition theory, studies of the great feasts of the church, symbolism in byzantine art and all visual arts, systems of perspective, types and styles of garments, the practice of artmaking, evangelism, ecology, mural programming, the business of being an artist, photographing one’s work, the uses of icons in the life of the Church, church architecture, depicting contemporary saints, and much more. A lot of this material is addressed in Aidan’s big book, but it is always preferable to have group discussions with the author himself about all these things in person. I’m not much of a book reader anyways (my attention span is stretched at the length of a typical OAJ article.)

Seraphim: Shropshire really is beautiful! One of the days I was there, Aidan’s protégé Martin Earle brought me to see only a few of the 12th century stone churches in the area, and we walked through sheep pastures in the foothills of mountains which he told me had inspired Tolkein as he developed his stories! During my visit, I was inspired to see the class working together in one room, under Aidan’s caring guidance. What was it like to study in a group like that?

Baker: It was wonderful to learn and work in a group like we did. The camaraderie and fellowship added a fullness to the learning process that I wouldn’t give up. In my opinion, having a small group like we did is ideal. To begin with, the pressure of performing up to your teacher’s expectations is lessened by having a cohort. If you were negligent in your homework since last class, there is always someone else who was negligent as well; so the guilt is less intense. We also each develop unique strengths that shine more and more as time goes on. One student will be a master at gilding, another at garments, another at faces, another with lettering and calligraphy, another with the subtlety of translucent paint layering, another with the spiritual zeal embodied in all the figures. Also, in class discussions about any given topic you get a wide spectrum of viewpoints. My particular class includes students originating from England, Bulgaria, Greece, Ukraine, Italy, and the Cayman Islands. We come from Orthodox, Catholic, and Anglican backgrounds. In my mind this diversity is an enriching factor in our education.

Secondly, working in a group for days at a time helped us stay on task and moving forward. Sometimes I fantasize that working alone would remove all distractions and maximize efficiency; but painting with other people actually spurred me on to be more focused and productive. When we were talking too much in class Aidan would remind us to get back to work. He would also set us goals to complete by the end of the day, and I would not have been so ambitious on my own. Aidan says he would rather us fail boldly and fantastically than be timid and cautiously adequate. This is a lesson I still need to let sink in. It can be intimidating to attempt new skills that are uncomfortable, but it’s critically important to push through fears of failure. Being part of a group helps a lot. You share in each others’ victories and defeats.

I also loved how Aidan handled critiques during class. The main way this happened was that one at a time we would come to Aidan’s desk while everybody else was busy working, and he’d critique our work. This had several benefits. First of all, we could all apply our eyes and hands to the works in front of us while simultaneously overhearing Aidan’s critiques. This had the virtue of reinforcing basic principles of the craft by repetition. Aidan would repeat the principles he had taught in lectures over and over again to each student, which helped drill them into our memory. It’s also great to learn from the critiques of others when you yourself aren’t in the ‘hot seat’ so to speak. Secondly, over time I noticed that Aidan calibrated his critical feedback to the measure of each student. He did not thrash students who needed lots of help, nor did he overly flatter students who made great progress. No matter how advanced any of us got, he always had about five minutes of critical feedback to give, which in my mind, is about as much as any of us can bear anyhow.

Now that the course is over I definitely miss my classmates, as well as the general dynamic of having colleagues to share space with while making art. This interview is taking place in the context of a worldwide pandemic that has many of us in quarantine or some measure of social distancing. Such a backdrop accentuates our awareness that we humans are generally at our best in community. We pray better in community; we work better in community; we learn and love better in community.

Seraphim: Amen to that, brother! Yes, this learning atmosphere sounds wonderful. It was moving for me to witness Aidan’s pastoral approach to instruction during my visit. Do you have a story for us about working on one of your assignments?

Baker: There was great solidarity among the students when it came to technical difficulties: gilding disasters, spontaneously self-destructing gesso, sub-layers of egg tempera coming up when painted over, and the temptation to give it all up, eat the eggs and drink the vodka.

One day we were all grumbling about our difficulties learning to make fine calligraphic strokes with a brush. I counted no less than 13 things Aidan had advised us to bear in mind when making a single stroke. At a certain point Aidan admonished us that we all needed to put in the hours of practice required, no getting around that fact. Once more he called us all to huddle closely around his desk for a demonstration of the proper technique. As we all leaned in to watch, he gave the analogy (in his native New Zealand accent) that it’s like being a “ballet dancer”. He probably had in mind the long hours of practice and self-mastery required of the ballet. However, after a few seconds holding our breaths, half the class looked up at each other. Had we just heard him say learn from the example of “belly dancers”!? After an initial uproar, an earnest debate broke out over the relative women’s health benefits of belly dancing, the hilarious details of which I’m a little too embarrassed to relate here. Anyways, it was not only beneficial working together, but usually quite fun.

Seraphim: I’ll look forward to an article from you on the lessons iconographers can take from belly dance technique!. In the meantime, could you give us a brief sketch of the theme of your thesis paper for Aidan’s class?

Baker: The title of my paper is, “Icons and Shame: How the Church’s Sacred Images Can Offer Spiritual Hospitality to Vulnerable Viewers”. In brief, the argument of the paper is that contemporary iconographers and commissioners of iconography would do well to see their collaborative work as a ministry to viewers who are in need of pastoral care. Our present generation of viewers comes to the icon bearing wounds of toxic shame; and some ways icons are fashioned bear the potential to exacerbate or alleviate that shame. The paper describes the phenomenon of shame as a natural response to broken communion, the role of iconography as a ministry of the Church, and three general strategies contemporary iconographers can employ to help contemporary viewers heal from wounds of toxic shame. I hope to share the paper more widely soon.

Seraphim: Fascinating. Yes, this is beautiful, how that urgent question of art – how to speak to people of our time and place – is for iconographers a pastoral question. It seems this is central to your calling to iconography. On your website, you say, “I make icons for my generation – in that we are psychologically complicated, troubled, ashamed, and insecure. We struggle to find the sobriety and courage to turn our true faces to God in faith. The Church’s icons are here to help us in this struggle.” That message resonates with me. You mentioned earlier that you feel you have a lot to say through your art, which you were concerned might not have a place in iconography. Perhaps these themes represent the ways you see your creative voice coming through in your icons?

Baker: What a kind thing for you to point out. I’m not sure I had quite thought of it that way before, but you’re probably right. I wish icons could heal people from their shame and restore them to communion with God, but I fear that’s beyond their power. What I do hope our icons can do is offer viewers encounters with beauty, sober reality, consolation, a sense of being seen on the inside and outside with mercy, and a token of hope that shores up the soul as she seeks to gather her courage to turn as much of herself to God in repentance as she can.

You know, icons usually convey truthful messages in their content and symbolism, but it’s still easy for us to despair in the face of Truth; or to hide parts of our real selves from that Truth. I want the Church’s icons to not only be faithful to truth in an objective way, but to run out to meet the prodigal viewer with open arms of hospitality, so to speak. I believe beauty can do this. Iconography is an invitation, a greeting, a spiritual embrace. It communicates Grace to the person through the eyes, like a sacrament.

Our generation is deeply insecure, ashamed, afraid, troubled, and lonely. Are we ultimately and profoundly alone? If not, are we actually loved in a personal way? Will all finally be well in the end? Are we really seen and valued? Is all of who we are really welcome in God’s presence? Do the commandments given to us by the Church lead to fullness of life, or restriction and oppression of life?

Our intellect may have learned the catechetical responses to these questions decades ago, but for reasons inaccessible to us, our soul has serious blocks to incorporating those affirmations. In Western society we have especially lost the simplicity of faith. We are tied up in knots that our intellect cannot untangle. I know for myself and many others, we want to believe that God is all-loving; we do. But there are parts of us that just cannot trust that yet, and indeed think and act as if that were not true.

As much as we try to ‘get over’ these thoughts and feelings, we are not able to overcome them on our own. A counselor, spouse, mentor, or friend can help us get a clearer picture of how we got here. Many of our wounds go back to our family of origin, our early childhood development. And there may also be chemical or hereditary vulnerabilities in play. Eventually a measure of healing may be found in loving communion with trusted friends, therapists, children, or other figures in our lives. Some of us may greatly benefit from medication or other health and wellness protocols. We can also find solace in the beauty of the natural world, and in works of art, music, and literature. Thankfully the Church also offers care and healing on many fronts through the gifts of the holy mysteries (especially confession and the Eucharist), and through works of mercy and beauty. One such therapeutic gift is undoubtedly iconography.

Going back to your earlier reference to my doubts whether I could existentially survive a transition from contemporary artist to iconographer (so very dramatic am I) – Yes, I do think leaning in to iconography’s potential to offer pastoral care to the viewer helped make space for me personally to inhabit the role of iconographer in a way I didn’t always know I could.

Seraphim: Knowing Aidan’s kind and pastoral nature, I can see why you say you could not have found a better guide. In the icons you have completed to date, I see you working out the vision you describe especially through facial expression – you are very sensitive to the viewer’s ability to connect with the eyes in your icons. The people you depict look like they are ready to be in hell with you, but they are not in danger of being sucked in by it!

Baker, do you see this as a special time for the liturgical arts? As you venture into the field of iconography, and specifically in our context of the United States, how would you describe what makes you hopeful and encouraged for the work ahead?

Baker: What a kind report you give about some of the icons I have made, and noticing their facial expressions. I thank God for that.

Is this a special time for the liturgical arts? I do not know. It’s the only time we’ve got isn’t it? And we are lucky to be here. When I personally think about the future of the Church’s liturgical arts and my own fragile involvement in them, my anxiety surrounding all the dangers and pitfalls tends to roar louder than my optimism. Can iconography as a ministry ever make significant headway in an ecclesiastical context where its product is viewed as a commodity, and competitively bid on a cost-per-square-foot (or square-meter) basis? Will my family meet financial ruin in my service to the Church’s beauty, due to my own inadequacies and weak character? Will I sacrifice the important things of life (family, love, community) in the pursuit of artistic perfection, and ultimately fail at both life and art? Will the next generation destroy what this generation creates?

That all being said, I do also have fantastic visions. That we are on the crest of a golden age of the Church’s art, and that I may have some role to play in that revival, crafting formative masterpieces that will outlive me and be looked back on as evidence of Salvation in my own life and in my community. Thus do I vacillate between despair and vanity. Maybe I’m not the best person to ask about the future.

But I would like to leave this conversation with one parting thought about the work ahead. The iconographic tradition is barren when it simply aims to recreate the artistic accomplishments of the past. Not all will agree with me in this judgment, but I find fundamentalist efforts at iconography usually adequate at best, and at worst, soulless aberrations that must be looked away from in the search for connection with the Living God. However, when the icons on the walls of a temple are made by a bright soul who is well-studied, possessing a courageous spirit, and enwrapped in her own personal striving for union with God, her icons can be birthed from the prayers of (and addressed to) the specific faith community they inhabit. Thus does the Tradition come alive in our epoch.

In our churches we do not replace the homily of our priest with a pre-recorded podcast; nor the voices of our chanters and choir with digital audio recordings played over a sound system. No, the homily is from a servant of God among us, and addressed directly to us. The voices of our readers and singers are our own best voices, lifted in worship anew every day.

I hope to see in my lifetime, icons and churches full of icons made by my contemporaries that are so much richer, nourishing, grounding, and engaging than any reproduction of a classic icon we have ever seen. Because we are still the Church. The same Holy Spirit that inspired Christ’s Apostles and every generation of saints is still alive and guiding us, now as ever. I think we will be surprised with a joy and humility akin to what would have struck the Philippians or Ephesians when they opened the letters that St. Paul wrote specifically to them.

Some of these icons are being made even now by friends of mine such as yourself, Seraphim, while many of these icons do not yet exist. So we cannot yet appreciate how beautiful and directly meaningful these images are going to be to our communities, and to our generation. But that is all in God’s hands.

“My sheep hear My voice, and I know them, and they follow Me. And I give them eternal life, and they shall never perish; neither shall anyone snatch them out of My hand.” (John 10:27-28 NKJV)

Baker lives and works in Austin, Texas. He can be contacted for commissions and inquiries at his website.

If you enjoyed this article, please use the PayPal button below to donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

I find a deep sense of honest spirituality permeating the interview. Thank you for that. I get the impression that, at least in the different churches I visited through the last decade, there is a need for worship “in Spirit and in Truth”. But would you not agree that one cannot express such worship without first meeting the Exalted One? Along these lines, I feel strongly that the writing of an icon is first a spiritual and worshipful act, and only then a matter of art (or craft). You both set a good example. Thank you.

Thank you for your kind words Emmanuel. Regarding your question of the prerequisite experience of “meeting the Exalted One” in order to worthily depict His icon, I have two thoughts. First of all, yes; and the masterful Anton Daineko wrote expertly about this in his article here: https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/the-living-icon/

A worthy passage from that post:

“In my humble view, the iconographer, throughout his whole creative life, strives to depict just ONE image of Christ – or Mother of God, for that matter – trudging toward them along a thorny path overgrown with different styles, techniques, and artistic perspectives. And each new icon is yet another stroke added to this one image which the iconographer had been trying to grasp from the very beginning but which has always been elusive. With the passage of time and the painting of many icons, the image becomes increasingly clear and distinct. This quest has a noble goal: to depict God as He really is, to cleanse His image as much as possible from all distortions and impurities of artistic style, momentary personal preferences, and other chance details.”

And a second thought: not all iconographers have heavenly visions. Not all priests have seen the uncreated light during the holy Liturgy. Not all monastics have unceasing prayer of the heart. But shall we despair of putting our hands to the work before us? No. Each of us having the image of God imprinted on our inner being, struggle forward the best we can in repentance. We are members of the body of Christ; and members one of another.

Indeed Emmanuel. One needs to know the Lord and His saints through the Holy Spirit in order to paint them.