Similar Posts

Continuing my photojournalism series highlighting Balkan churches, this post features interesting iconostases I photographed in Serbia and in the Kosovo and Metohija region.

These iconostases range from medieval to contemporary, and exhibit a remarkable range of styles. I find it fascinating to view them grouped together, and consider that there are such diverse solutions to a common liturgical function.

I will start with iconostases of the templon-screen typology – the early-medieval form of altar screen in which stone columns and a lintel form a structure from which to hang the curtain. Originally these templons contained no icons, but in the later middle ages, icons were added atop the lintel, and then between the columns. (It is important to remark that this process did not transition the screen from transparent to opaque, because the curtain was there all along. Rather, it replaced the iconography that was likely embroidered or woven into the curtain with iconography painted on panels.)

Patriarchal Monastery of Peć – Church of St. Demetrios, 14th Century. The original templon screen is reconstructed from substantially intact original stones. The icons are modern.

Gradac Monastery, built 1277-1282. The church has been reconstructed from a ruin, with enough original parts of the templon surviving for an accurate reconstruction.

Studenica Monastery, built 1190-1196. The templon screen is a modern reconstruction from archaelogical evidence.

Next come photos of the late-medieval/Renaissance form of iconostasis, in which a wooden framework holds tiers of icons as a continuous wall. This form of iconostasis emerged in Russia and spread across the Orthodox world.

Patriarchal Monastery of Peć – Church of the Holy Apostles, 13th Century, with later iconostasis of renaissance style.

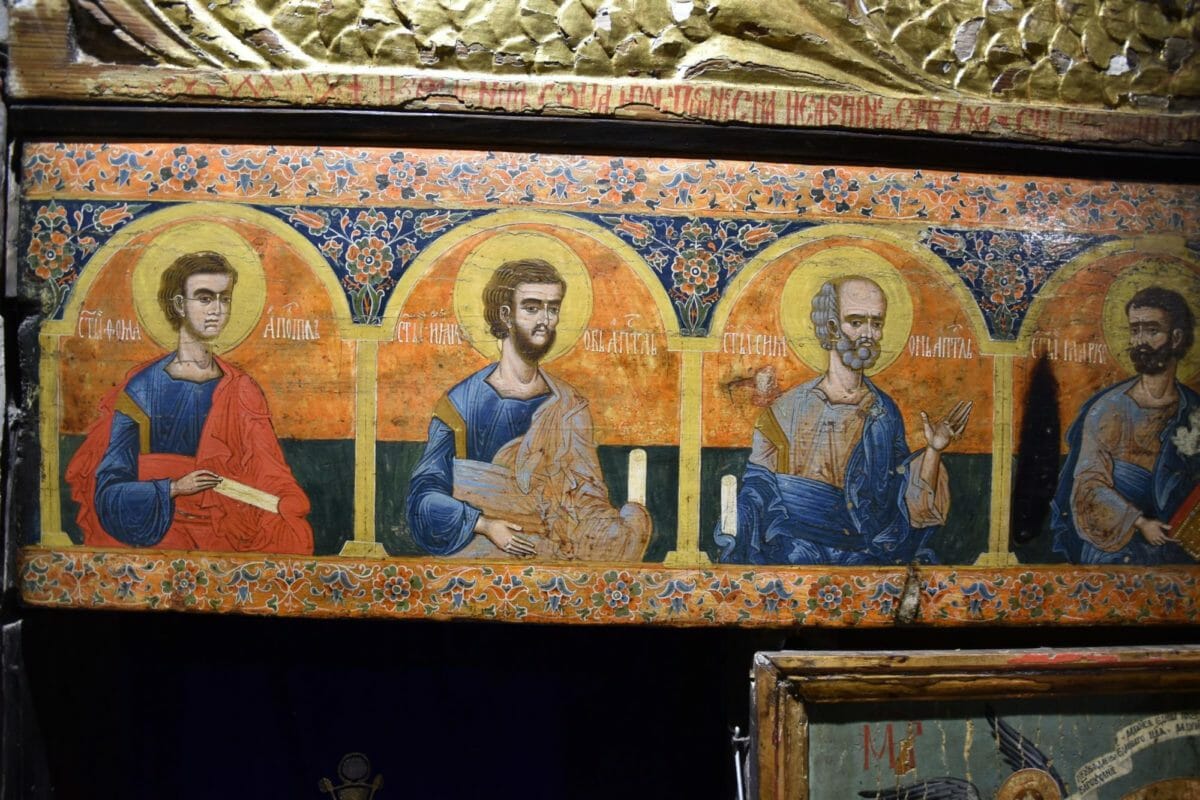

Crna Reka Monastery, 14th century, with a simple iconostasis made from fine old panels of many periods.

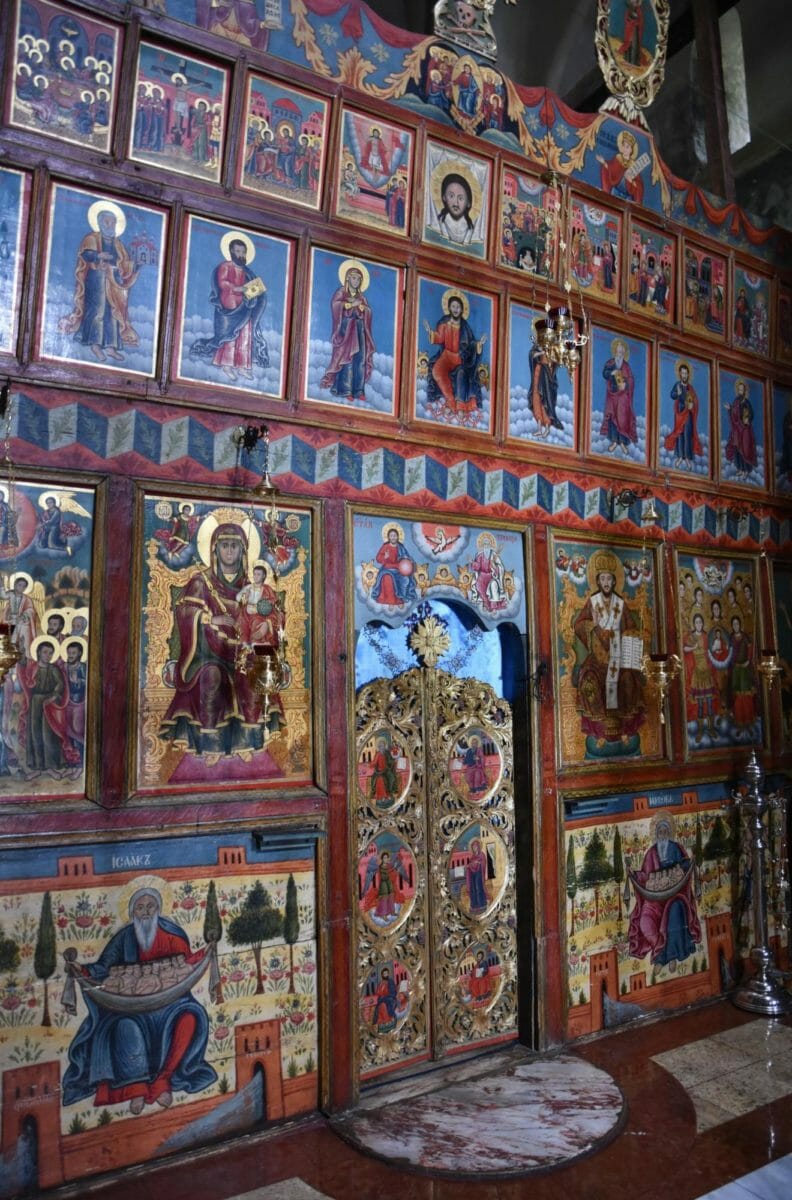

Entering the baroque period, as icon-painting declined in importance, the decorative woodwork of the iconostasis increasingly ornate. The riot of carving and gilding on a baroque iconostasis is meant to evoke the beatific vision – a sudden and ecstatic encounter with the glory of the Heaven, overwhelming to the senses.

Saint Nicholas Church in Zemun, built in 1745, with the baroque iconostasis dating from 1761. Belgrade.

In the 19th century, iconostases entered their neoclassical phase. These screens were the purview of professional architects, designed according to the rational system of the Greco-Roman orders. These are the iconostases of the early-modern age – intellectual, orderly, informed by the latest archaeological finds and the good taste of academy-trained artists.

Saint Michael Cathedral, Belgrade, built in 1837. The modern kings of Serbia were crowned before this splendid neoclassical iconostasis.

Finally, we come to the romantic era, which (with regards to iconostases) starts at the end of the 19th century and arguably continues to this day. Screens of this movement revive medieval forms and styles, but interpret them freely, amalgamating ancient and modern ideas of art and architecture. While these revivalist screens often have excellent quality painting, I usually feel that the overall presentation lacks the impact of older screens of more confident and singular style.

Ružica Church in the Belgrade Fortress. The iconostasis dates from 1925. The woodwork represents the romantic revival of pan-slavic decorative forms popular at the time.

Ružica Church – detail of holy doors. These exquisite panels were painted by a beloved Serbian martyr and noted artist- Saint Rafailo of Šišatovac.

Saint Sava Cathedral, Belgrade. The contemporary main iconostasis exhibits an eclectic revival of Byzantine, Italian, and Slavic forms.

Lešje Monastery. A contemporary iconostasis of particularly eclectic and whimsical design, made mostly of ceramic tiles.

If you enjoyed this article, please use the PayPal button below to donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

Wonderful!

Thanks Andrew!

Thank you for this photographic tour! It is fascinating to see how each period has its own uniqueness as popular art and craft influences the iconostasis.

This is wonderful, Andrew-Highly informational to see in terms of historic progression.

Thank you!

So nice! Iconostasis and icons in Žiča are beautiful.

I especially liked Ravanica with the use of the beautiful blue color overall and in the doors

[…] August 7, 2023Iconostases in Balkan Churches – Part 1: Serbia […]