Similar Posts

…I looked at Russian icon painting with new eyes, that is to say, I “acquired eyes” for the abstract element in this kind of painting.

–Wassily Kandinsky[i]

For better or for worse the traditional icon painting revival is indebted to modernism, in particular its development of abstraction. Although, as a traditional liturgical art, the icon is often hailed as the bulwark against modernist tendencies within the liturgical context of the Orthodox Church, nevertheless, it cannot be completely disentangled from the history of modernist painting. That’s the irony.

It was the late nineteenth and early twentieth century avant-garde, after all, that called into question the hegemony of naturalism and classical standards of beauty, as expounded by the French Academy. Along with this came the revaluation of medieval art, folk and tribal art, as part of the “primitivist” trend of the day. Hence Byzantine art, and the icon in particular, was hailed as an example of proto-modernism. This, among other factors, created the fertile ground for a more pluralistic approach to aesthetics, enabling the pioneers of the icon revival to conceptually frame their views in defense of the metaphysical implications of the icon’s non-naturalism against academic religious painting, which had usurped the icon’s centrality within the liturgical life of the Church.

In other words, the secular and religious spheres cannot be disentangled, neither from the developments of modernism, nor the revival of the icon—the two have always been, not just in tension and opposition to each other, but also inevitable dialogue. However, the dialogue between art and religion, as it unfolds to the present day in contemporary art, is one that has been for the most part ignored, if not maligned, as marginal to the concerns of serious historiography and art criticism. Only in recent decades have we seen a major interest in the reassessment of this history, acknowledging that it’s not only as a simple matter of estrangement, but rather one of complex dynamic exchange and realignment between competing, if not seemingly contradictory spheres.[ii]

Nevertheless, challenges remain. Those addressing these issues from within the religious context are often looked at as suspect or compromised by their coreligionists, while those within the secular sphere of art history and criticism are dismissed as discredited for their “naïve” concern for things “metaphysical.” Speaking from within the religious context, I’m willing to deal with the consequences, in an appeal for more honesty, nuance and accuracy. But, as Yve-Alain Bois resisted the “blackmail” of those who sought to discredit him for his approach to formalism, so those within the secular sphere, who take the religious dimension of art as worthy of critical inquiry, must also resist the “blackmail” of a bigoted secularism that forgets the source of its own staunch defense of freedom of thought—religion.[iii] The specter of religion cannot be escaped, after all. One art critic that has stood out in uncompromising resistance for decades is Joseph Masheck, former editor of Artforum.

The following interview with Masheck arose from a sabbatical research project on contemporary religious art, conducted in 2022 by Joachim Pissarro, Professor of Art History and Director of the Hunter College Galleries, Hunter College, CUNY/City University of New York, and former curator at MoMA. The project began with the question: Why is there no contemporary religious art? The initial objective was to identify works that were both made during the contemporary era (1960-present) and are directly religious in nature, focusing on those that reference Christianity. It became clear, however, that contrary to the original research question, there was an abundance of art that fit the initial criteria. However, these wildly diverse forms of art that display a religious content have tended to be castigated, or sidelined through various strategies of ignorance or edulcoration.

The research findings were divided into two categories: works of art that were created by secular contemporary artists in reference to Christianity, and works that were created within a Christian context during the contemporary era. The latter focused primarily on work made by Orthodox Christian iconographers. In considering these works, the thinking was informed by the writings of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, whose concept of the aesthetic vs. rhetorical approach to creating art mapped directly onto the two categories. It was at this stage that I had the privilege to begin close collaboration on the project with Pissarro, assisting him with research on iconography in both historical and contemporary contexts.

Inquiry mainly centered around the following questions: How can we decipher, with legitimacy, contemporary religious art that was created sincerely rather than ironically? How should we approach contemporary religious art that addresses an art historical tradition rather than a Christian one? Why is it that many contemporary art spaces are comfortable with art that is vaguely or obviously spiritual, but rarely create space for or offer legitimacy to art that is explicitly religious?

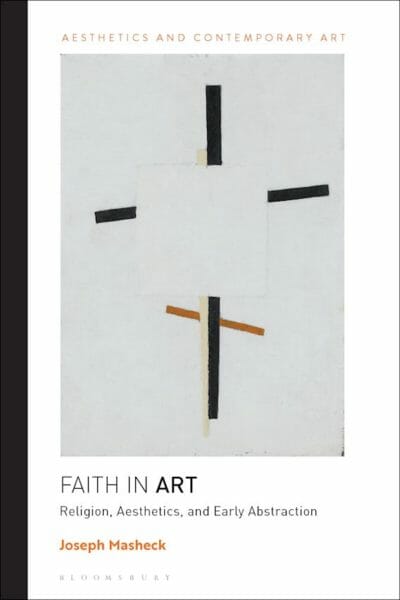

While deliberating these questions we decided to engage in conversations with Masheck, who has written at the intersection of religion and contemporary art for decades, taking particular interest in the important role the icon has played in the development of abstract painting in the 20th century. The interview presented here is the fruit of these conversations. As David Carrier recently put it: “For a long time, art criticism had been a mostly secular enterprise. Masheck always resisted that way of thinking, arguing…for the grounding of modern art in religious life. His early writings presented a stunningly original view of the nature of painting, an account relevant both to historians of early abstraction and to art critics.”[iv] In his most recent book, Faith in Art. Religion, Aesthetics, and Early Abstraction (2023), Masheck expands on his earlier theorizing, giving us a thorough analysis of the metaphysical concerns of the pioneers of abstraction, in particular their indebtedness to Christian thought and “revealed religion.”

For some Orthodox Arts Journal readers, this interview might appear to be a bit incongruous to the main thrust of our concerns—the liturgical context. However, as the attentive reader will have discerned by now, our Theory section is meant to allow for an expanded field of inquiry to be taken into consideration—mainly art theory matters that converge with and yet fall outside the icon painting tradition and other liturgical arts. The hope is that this will serve to broaden the scope of Orthodox engagement with contemporary art theory and scholarship, thereby helping to enrich our conceptual framework and approach, not only to the practice of liturgical art, but also the non-liturgical work being created by artists within the Church today. The Theory section aims to accomplish this enrichment in ways that break beyond simplistic ideology and insularity, without the compromise of the Orthodox tradition. Hence while engaging in dialogical rather than polemical discourse, with scholars who are not part of our ecclesial affiliation, the Orthodox Arts Journal is not thereby endorsing all of their views. The enriching dialogue remains what it’s intended to be: a process of gradually discovering a different perspective, in a dynamic of mutual understanding and respect.

Joseph Masheck was editor-in-chief of Artforum from 1977 to 1980. He is Professor Emeritus of Art History at Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York. He has taught at Barnard, Columbia and Harvard. Masheck has also been Centenary Fellow of Edinburgh College of Art (University of Edinburgh), and a Visiting Fellow of St. Edmund’s College of Cambridge University. He received the Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award for Writing on Art, of the College Art Association, in 2018. His most recent book is Faith in Art: Religion, Aesthetics, and Early Abstraction (Bloomsbury, 2023).

Joachim Pissarro is Professor Emeritus at Hunter College/City University of New York, and a guest-lecturer at Holy Trinity Seminary of Jordanville. He was curator at the Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Painting and Sculpture from 2003 to 2007. Pissarro was also curator of Contemporary Art at the Yale University Art Gallery, and a Chief Curator at the Kimbell Museum in Fort Worth. His most recent book, authored with art critic David Carrier, is Aesthetics of the Margins / The Margins of Aesthetics: Wild Art Explained (Penn State University Press, 2018).

****

Pissarro: What kind of role has the question of religion played throughout the years as a facet of your theoretical development as an art critic and historian?

Masheck: I had phased out religion for about a decade from college in the early 1960s onwards. In graduate school my major field was Renaissance and Baroque art, especially the latter, and above all, architecture, which I studied formalistically—as much as possible as abstract art. Religion crept back in as cultural politics in a 1973 dissertation on eighteenth and nineteenth-century church building in Ireland, when that subject had seldom been handled in a cosmopolitan way. Before long I was back in the (Catholic) church, thanks to a then wonderful (Anglican-style) parish liturgy and a new sense of reform.

Pissarro: What has been the general reaction, in the art world and academia, towards your focus on religious and theological matters, as another legitimate area of inquiry worth exploring within the field of art criticism?

Masheck: I haven’t really been concentrating on religion for the past 50 years; I’ve been a generalist art historian concerned with criticism (as my mentor Rudolf Wittkower hoped). But religion is part of culture as well as part of life; and what has happened, I think, is that the once lively religious culture of New York dried up once the vain money-worshippers came to town in the ’80s. That was quite noticeable to teachers and to anybody ecumenically inclined, as I was.

Pissarro: Tell us a bit about your experience as an editor-in-chief for Artforum during the late 70s. How important was the topic of religion to you as an editor during that time, both as a field of inquiry into the history of modernism, and as a way of framing the contemporary debates surrounding the continuing relevance of the practice of painting?

Masheck: It was a very bad time for painting, notably abstract painting, which I loved. It was so easy to blame it pseudo-radically, almost as if for market capitalism itself, even though few new modalities ever really rocked the capitalist boat. (Minimalist sculpture was something else entirely: it had good reason to be so immanentist, particularly in don’t-blame-me relation to the surrounding culture during the Vietnam War.) But I suppose my own obsessively historical as well as theological tropisms had me anticipating your next thought by searching out the neglected, non-Western European iconic tradition, on such a solidly anti-naturalistic, even stylized, and in that sense quasi-abstract, basis.

Fr. Silouan: One of your seminal essays during your years as editor-in-chief of Artforum was “Iconicity.” After all these years how do you now see the role the icon painting tradition has played within the development of modernist painting?

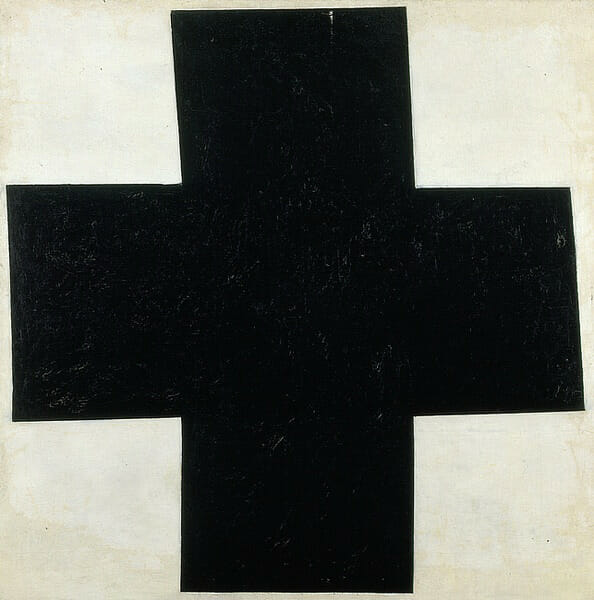

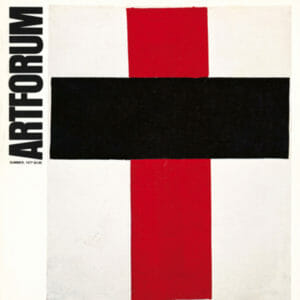

Masheck: Yes, to continue (!): note that I was never interested in iconoclasm, which tedious academics are always prepared to rake over yet again. Only the question of painting that deserved to pass muster beyond iconoclasm ever concerned me, in its decided anti-naturalism. I believe that painting is essentially metaphorical—as Jakobson proved that half of language is—and the icon glories in that. No wonder Rodchenko’s attempt to prove otherwise in 1921 with the triptych Pure Red Color, Pure Blue Color, and Pure Yellow Color is such a dud, as a mere stand-in for painting: it just won’t play ball, and that is simply not one way to play ball. Let me point out that that series of articles you mention—otherwise designed to show that there was indeed interesting contemporary painting going on—begins with the Western as well as Orthodox notion of a Crucifix: “Cruciformality,” with Malevich’s Hieratic Suprematist Cross, 1920 (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam), on the cover, as I designed it (all my Artform covers were planned by me except the last). Inside that issue, however, was Margie Betz’s classic article “The Icon and Russian Modernism,” also commissioned by me. Most people never got the East/West connection.

Pissarro: Do you make a sharp distinction between what is at times referred to as the “spiritual” dynamic, as compared to the “religious” impulse in modernism and contemporary art?

Masheck: Right, I always try to avoid the first term because it’s so slippery: it’s the opposite problem to “Absolute”—which, as one familiar with a literature on God, I never know what I’m getting into with a capital “A.” So I try to see whether “religious” is justified, sticking when necessary to Durkheim’s social definition.

Fr. Silouan: How would you delineate the relationship between the religious underpinnings in modernism and the Romantic tradition? In other words, can it be said that the theories of the pioneers of abstraction are indebted to, or are the logical outworking of the premises of Romanticism? Is there a better way to frame their theory beyond the vestiges of Romanticism?

Masheck: No one has asked me this before, and it’s important. I realize that historically speaking, German Romanticism is no doubt responsible for some of what I hold dear; but early on, I made every effort to resist sheer self-indulgent subjectivity. The formation of my own modernism, in college, relied on early modernist literary critics who resisted the pap of Romanticism and aimed for a compensatory classico-modernism: thinkers such as T. H. Hulme—as almost self-caricatural as he can be, yet in the serious orbit of Pound and the cubists.

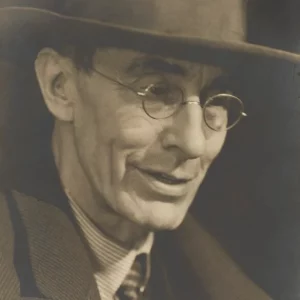

Roger Fry, by Ramsey & Muspratt, 1932. Bromide print, 11 3/4 in. x 8 1/2 in. © Peter Lofts Photography / National Portrait Gallery, London.

Fr. Silouan: How would you describe your particular approach to “formalism” or “formalist criticism” as distinct, let’s say, from Greenberg’s or Yve-Alain Bois’s? This in fact touches on the problem of form and content dichotomy, which you address in your most recent book.

Masheck: My own formalism owes nothing to either of those writers because it obviously derives from the analytical formalism for which Columbia art history was long famous—as central to art history as logic to philosophy. Clement Greenberg was in actual fact a late New York formalist. Face it: Roger Fry once worked at the Met, and his books were published by Brentano’s here; and that’s not even counting Arthur Wesley Dow at Teacher’s College, Columbia, a recognized formalist influence on artists as important as Georgia O’Keeffe. No; I already had Columbia bachelor’s (1963) and master’s (1965) in art history when my Columbia graduate school friend Clark Poling showed me Greenberg’s brand-new Art and Culture. Even a decade later, when I had been teaching at Barnard for six or seven years and was pleased to greet young Bois in my office at Artform, our art world was still largely conversant with formalism. BTW, I don’t think I make a point of any form/content dichotomy in my book: I tend to suppose that I operate with a much more incarnational estimation of the art object as idea taking up residence in material.

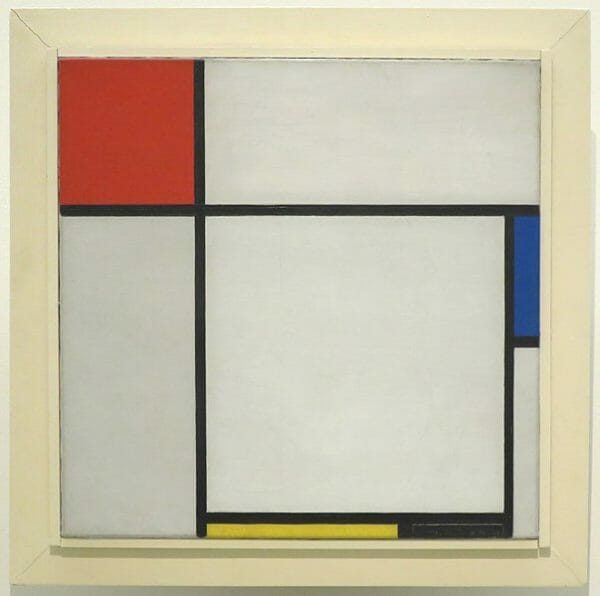

Composition, Piet Mondrian, 1929. Oil on canvas in artist’s frame, 17 3/4 x 17 7/8″. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, NY.

Fr. Silouan: I recall, in graduate school, having a discussion with a professor about Mondrian’s work and its theoretical underpinnings, mainly how it embodied a very specific metaphysics. My contention was that Mondrian’s notion of the Absolute, and its relation to the inner structure of reality, could not be ignored in the interpretation of his pictorial approach. To say the least, the professor did not want to hear it, he just dismissed Mondrian’s theoretical claims as completely irrelevant: “Don’t take those theories at face value,” he muttered. He might as well have uttered Frank Stella’s famous dictum: “What you see is what you see.” This anecdote brings to mind a previous conversation we had, in which you mentioned the problem of a “positivist” approach to abstraction. What did you mean by that term or attitude and how would you describe your own exegetical approach to abstraction?

Masheck: Most professors don’t know—and maybe sometimes don’t want to know—that after Mondrian gave up on his father’s church he took and passed a confirmation course in a new “Neo-Calvinist” church in Holland. Suffice it to say that Positivism only accords whatever can be measured the respect of truth; and that effectively abolishes anything metaphysical. We can’t tackle that whole posture here, but in my book Kandinsky does a good job of getting beyond its excessive skepticism. Given that every text demands interpretation, I try to do for painting and other artworks what everyone in the tradition of scriptural exegesis extending from Schleiermacher to Robert Alter hopes to do with Holy Writ.

Pissarro: Have you come across any contemporary artists in whose work we can discern a religious impulse, whether this be in the form of abstraction, obvious or implicit indebtedness to the icon painting tradition? Can religious themes and concerns be dealt with today in a robust manner, without the work disintegrating into a display of facile cynicism and irony?

Masheck: I almost said simply no; but on second thought I do know painters whose dogged pursuit of, let’s say, painterly truth, displays a high personal devotion to task. I don’t know what genuinely religious themes or concerns could “fly” today: I would suppose that they had something to do with justice and peace, but for me, that would have to be abstract (as in Mondrian) or close to it. I’m not, after all, “pushing” icons: I respect the tradition; but it’s not my faith, and I’m not about to question anybody else’s faith either. Yet I do actually know and admire a contemporary abstract painter who consciously and fruitfully engages the iconic tradition: Alfonse Borysewicz (b. 1957).

Fr. Silouan: It is commonly acknowledged that Theosophy and other occult or esoteric currents influenced the development of abstraction. However, the role Christian theology has played in this history is often undermined. Which would you say has played a stronger role, the Christian tradition or the occult currents of Western esotericism?

Masheck: Because I have shown that the principal founders of abstract painting were inured in what some of us still call “revealed religion,” the fair-minded reader can now decide whether private, gnostical secrecy was or was not more vital and significant in the beginnings of abstraction than the prospect of a necessarily social Kingdom of Heaven.

Pissarro: Can you tell us a bit about the general thrust of your new book, Faith in Art: Religion, Aesthetics, and Early Abstraction, recently released by Bloomsbury, and how it came about? Do you feel like your research has helped to clarify how Christian theology has played a major role in the early stages of the history of abstraction? Will you be discussing contemporary painters considered as heirs of this tradition?

Masheck: I’m not aware of any such tendency, but it might indeed be enlightening for contemporary abstract painters to take an interest in revealed religion: the present book shows that the founders of abstraction didn’t need to do that remedially. My thinking for it first centered on Lissitzky, in giving a keynote lecture for the theme “Art and Christianity in Revolutionary Times” for a conference of the Church of England body, Art and Christianity in 2012, when I spoke on “‘Convictions of Things Not Seen’: A Change from Suprematism to Constructivism in Russian Revolutionary Art”; and then, about Mondrian, soon after the first published translation of an important Neo-Calvinist treatise, for a Watson Gordon Lecture at the National Gallery of Scotland in 2017. When the pandemic came, I decided to expand my purview to cover these four founders of abstraction, consecutively: Kandinsky, Mondrian, Malevich, and Lissitzky. Frankly, I had that idea in the back of my mind, partly because my own tradition, the Catholic, is so philistine about modernity that it is alienated even from Malevich, while many Orthodox and others assume he was Orthodox just because he treasured the icon. And because some educated Catholics even assume that Kandinsky is a Jewish name, I wanted to expand the purview into the next generation to cover Judaism too. The book, then, is an extended historical speculation on the significance of an awareness of revealed, biblical religion—as against recourse to anything occult—in the origins of abstract art. Perhaps, in one way or another, it may foment concern with faith among contemporary artists.

Notes:

[i] M. Bill, ed., “Interview Nierendorf-Kandinsky,” in Kandinsky, Essays über Kunst und Künstler, Bern-Bümpliz, 1963. Translated and published as “Interview with Karl Nierendorf” in Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art, eds. Kenneth C. Lindsay and Peter Vergo (NY: Da Capo Press, 1994), 806.

[ii] See the introduction to Religion and Contemporary Art: A Curious Accord, eds. Ronald R. Bernier and Rachel Hostetter Smith, (New York, NY: Routledge, 2023), 1-18.

[iii] Yve-Alain Bois, “Introduction: Resisting Blackmail,” in Painting as Model (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press,1993), xi-xxx.

[iv] David Carrier, “In Praise of Joseph Masheck: Art Critic,” Counterpunch, August 4, 2023.

I’m so glad to find this article today, a few hours after a Russian History Museum zoom presentation on these issues in 20th-c. Russia with Joachim Pissaro had to be cancelled early through it because the burglar alarm went off at his home! He had had time to mention his upcoming book with Fr. Silouan Justinano, which I promised myself to look out for, and here is a preview of sorts that brings to my attention a highly relevant new book by an author I did not know, Joseph Masheck. What a treat! I wonder if the same format of interview could be arranged with Davor Dzalto, whose book Schöpfung und Nichts I recently got, as a keen practicioner of astute in-depth cross-interpration of Orthodoxy and modern/contemporary art.

Never thought Piet Mondrian would be mentioned on OAJ!

Thanks