Similar Posts

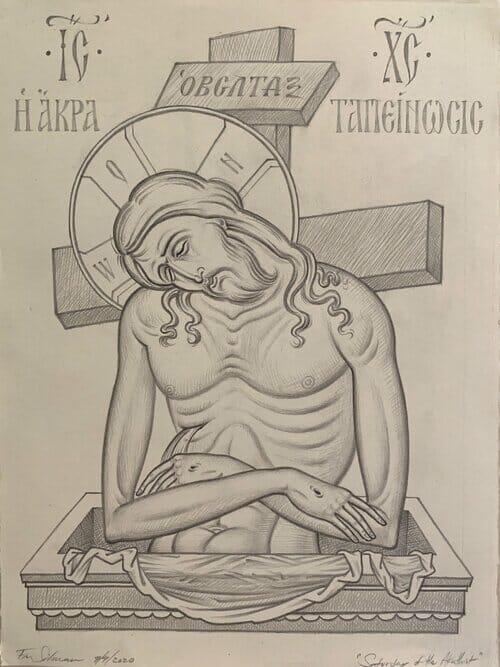

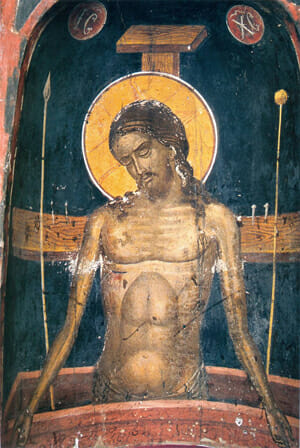

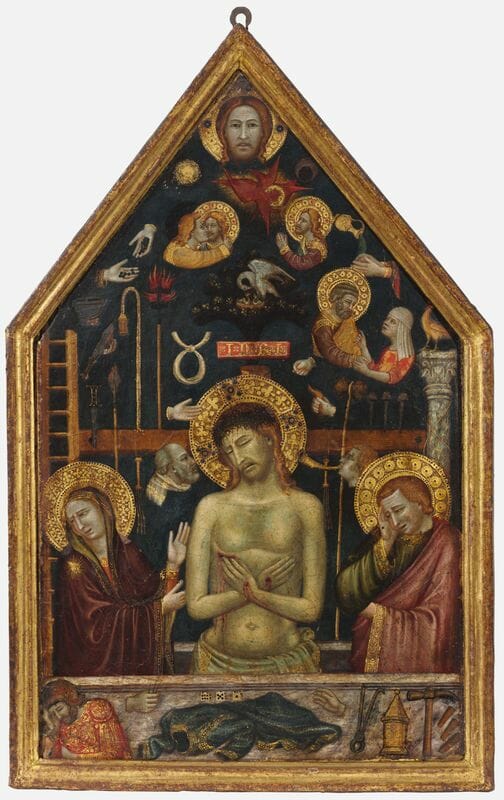

In Tradition and Transformation…Gadamer’s “horizon” helped me think in terms of a “communion of icons” (koinonia eikonon) or to think of icons as living these interpenetrating lives across time. Think, for example, of all the variants of the King of Glory/Akra Tapeinosis since the type first appeared in the 12th century. Each one carries its putative original but does so in its own conditions and time.

– Cornelia Tsakiridou

Akra Tapeinosis (inscribed The Deposition) bilateral icon, early fifteenth century. Tempera on wood, Byzantine Museum, Kastoria, Greece.

Fr. Silouan: It’s often taken for granted that an icon is to depict beings as transfigured or deified. Hence, the stylistic peculiarities of traditional icons, namely its non-mimetic or abstract qualities, some would claim, are considered crucial in accomplishing this goal. In contemporary debate, however, others would say that this is only a very modern, 20th century icon revival interpretation, going counter to patristic theology, which defines an icon primarily as a likeness, the depiction of the outer form of the subject, not the capturing of spiritual realities. The Byzantines, after all, valued an icon’s lifelike qualities, not its abstract stylization. It’s quite obvious that the essence of beings and divinity are undepictable. But, let us just consider for a moment pictorial form in general: Is it possible to say that the interpretative potentialities of form in painting can suggest spiritual realities, even a deified state, without running counter to the patristic view? Can we speak of a poetics of pictorial form which transcends literalist mimesis and thereby captures and enables us to see more than meets the eye? Can we even dare to say that pictorial form can, in some mysterious and dynamic way, embody the logoi of beings?

Cornelia Tsakiridou: It seems to me that enargeia helps us respond to this challenge. I do not think that patristic theology is so superficial in its understanding of images. On the contrary, Byzantine experiences of icons, as we see in ekphraseis, but also in the visuality of patristic theology (especially in its more profound and mystical moments) were by no means experiences of surface resemblances. Nor were they merely rhetorical tropes and exaggerated expressions of piety or idealization as some students of the icon (many from art history) tend to think. Look at our hymnography as well, especially in Syriac (the beautiful work of Sebastian Brock), for example St. Ephraim the Syrian or St. Romanos Melodos. There is surface and depth, but also concept and form, visuality and aurality, interpenetrating, opening into paradox, folding again into sense, ever dynamic and alive. I think that ideological modalities in Orthodox thought in the 20th century have prevented an open reading of patristic theology in the case of the icon. An example is the fortress mentality of many iconographers and theologians in Orthodox countries, faced with modernity and the supposed perils of western influence. Postmodern thought (poststructuralism) has encouraged us to abandon that state of mind and recognize transcultural modalities in icons from the early years of their existence, but also to return to patristic texts and discover polyphonies and liminalities in them that are commensurate with the spiritual realities that inform them. So, in that respect, we have a lot of work ahead of us. There is a tendency to pay lip service to our tradition and then “suffocate” it with ideologically informed restrictive precepts that in some form or other nurture or justify our complacency. I think we need to be honest about that. In my view, the iconographer holds a prophetic position within the Church (as does the architect and all those that shape the physical spaces and forms in which we experience the mysteries of our faith). He or she is not there to simulate and decorate (using different stylistic keys) but to awaken our eyes, senses, and minds to these mysteries.

Fr. S: Beauty is an adjective too often ascribed unconditionally to the icon. But beauty, let us admit, is a very ambiguous and fuzzy concept. It has a long and rich philosophical and theological history that unfortunately tends to be oversimplified, if not completely ignored, in popular discourse. In ecclesial circles the word tends to be weaponized in culture war polemics against the perceived decadence of modern and contemporary art. Hence the traditional icon is hailed as spiritually “superior” because as a liturgical art it aims towards beauty, which is what all art should pursue as its raison d’etre, after all. But this polemical use of beauty, although it might at first appear to uphold aesthetics, actually ends up completely undermining the nuances and integrity of the aesthetic object. In the end saying something is beautiful just becomes a gesture of pious approbation regardless of the aesthetic reality of the icon being confronted. You touch on the complexity of beauty in your book, Icons in Time, Persons in Eternity, pointing out its limits and pitfalls as an aesthetic concept. What was it about the discourse surrounding beauty that you found unfruitful as a direction to take in developing a richer, more robust approach, and better understanding concerning the aesthetic implications of the icon?

CT: I clearly see your point about “beauty” as a gesture of “pious approbation.” The concept does indeed function that way in the case of icons and art more generally. In a way that is inevitable, since that is how the term is used in ordinary speech, to convey approval, admiration and some sense of ideal status or form attributed to the object or person at hand. I think I have not dealt with “beauty” in depth—something that I would like to do. In part, that was because when I started working on icons, I was seeking alternatives, having seen the concept being used rather uncritically in Roman Catholic discussions of sacred art but also in Orthodox studies that (odd as it might sound) did not approach the subject aesthetically. I think that in the back of my mind was the idea that I could work on it later, and perhaps this time has come. In any case, to return to your question. Let me suggest here that beauty is the condition of perfection in a thing or person, a perfection commensurate with its hypostatic being (for example, a person realizing this or that quality in its specific act of being itself). Since such perfection is not reached without divine grace, beauty is a hagiopneumatic state, where human life or the being of anything, partakes of the plerotic energies of the divine life, according to its measure or capacity. If beauty in that sense is always hypostatic, then we cannot generalize or offer a matrix for it (like the Platonic symmetry, proportion etc.). This means that each icon, in its particularity and specificity, is beautiful when it realizes in its aesthetic being the qualities that characterize its subjects (iconically, within the limitations of its art form and medium). Since image and imaged are hard to distinguish, it is also the image as such that partakes in that hagiopneumatic reality and may in that respect be characterized as beautiful. This suggestion, of course, is preliminary, it needs to be thought out and developed, but it does outline a certain direction in which we may rethink or rediscover the concept in an Orthodox context but also more broadly in the Christian tradition.

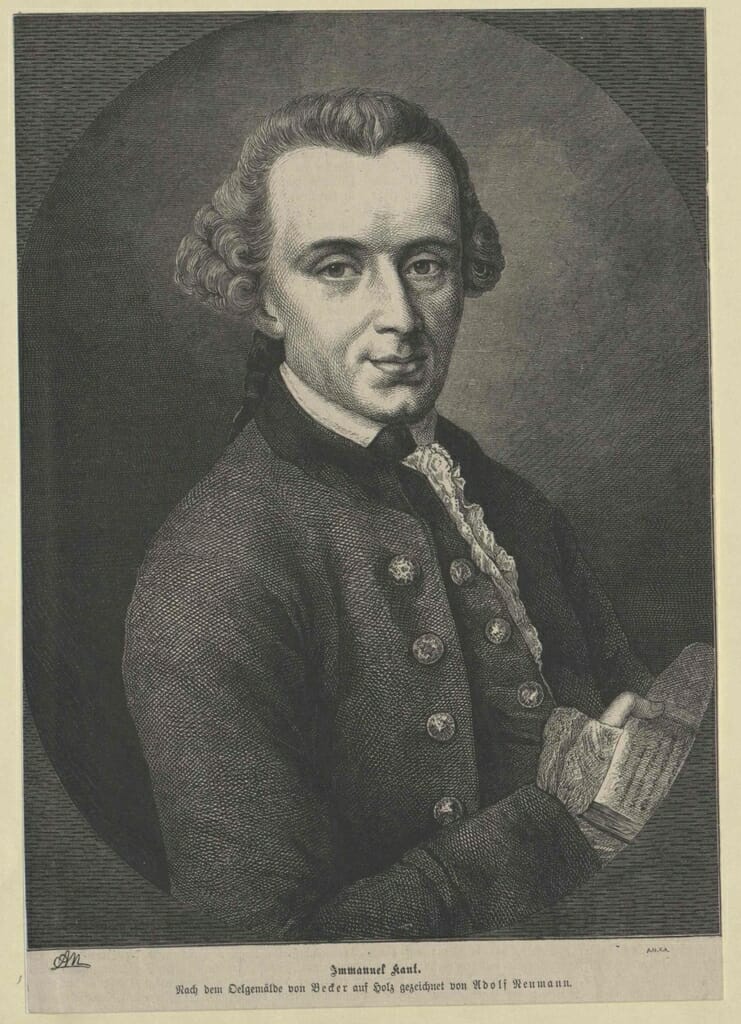

Fr. S: I have often discussed how the icon doesn’t fit the autonomous Fine Art model. It cannot be reduced to an aestheticism, a fixation on surfaces and taste, that undermines its spiritual content. The icon rather presupposes a premodern paradigm — the traditional view of art as “techne” — in which the question of aesthetics cannot be disassociated from functional values and collapsed to a notion of “disinterested contemplation.” But, on the other hand, in an attempt to avoid a superficial aestheticism, we can end up making an artificial distinction between a work’s spiritual and aesthetic aspects. The two are inextricable. Doesn’t the spirituality of an image become manifest precisely through the specificity of its form? So isn’t there some room for the Kantian model in treating the icon aesthetically, without compromising its spiritual and functional integrity? Would it be fair to say that you have done this implicitly?

CT: I think this is a beautifully framed question. In my view, Kant can be engaged from an Orthodox standpoint. Take, for example, his notion of “aesthetical ideas,” those animating modalities deep inside the mind of genius that expand concepts without intellection and make a work “spirited.” Where present, these ideas animate or energize the viewer’s imagination (always according to Kant). Instead of the Kantian energies or ideas, icons are manifesting spiritual realities (the participation of the entire person in the life of God). In other words, Kant prompts us to consider that the aesthetic dimension (in exemplary works of art) is never just surface. Rather, it is the expression of immanent energies in the art object (for Kant reflecting the energies of the charismatic genius—in his view, a phenomenon of nature). It is a movement inside the image that gives the impression that what we see is rising from its depth (Greek anadyetai, like a diver returning to the surface of the sea). Enargeia, of course, fits nicely in that context. Now, from our perspective, the icon, as we have seen, has reason to be that way. It partakes of the logoi of things and the life of God, according to its capacities. Here, we need to be careful not to aggrandize (or idolize) the icon and thus burden it with transcendent realities that it cannot carry—a matter of eusebeia, to recall St. Maximos, or giving beings their ontic due. It is, after all, an image and it is as image that we must approach it. So, the distinction between aesthetic and spiritual is understandable, but as I pointed out earlier, categories are there to be entertained and then put aside to rest—especially when it comes to matters of mystery and paradox. Categories are open, not closed domains: invitations for stasis and clarity so that movement can begin again (especially where the subject is inexhaustible). I think that that is what my work has taught me—taking scholarship, in this case, as an ongoing investigation or, if you wish, a participation, according to one’s capacities, in a subject’s truth. Kant has also taught us to look for the aesthetic in all things, rather than in the isolation of the art museum or gallery (or of some contemporary Orthodox churches that display their icons in a similar, detached and clinical, manner). Kant’s opening of the concept of the aesthetic is good because it resonates with Orthodox experience in some respects. We know from the liturgy that icons, incense, chanting, vestments, light, and architecture are intertwining, interpenetrating realities in which senses and mind participate, discover, and realign their differences and similarities. We may think of the liturgy as the great aesthetic workshop of Orthodoxy.

Mark Rothko, No. 46 (Black, Ochre, Red Over Red), 1957

Oil on canvas, 99 1/2 × 81 1/2 in. Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris.

Fr. S: We’ve discussed the problem of symbolism a few times and tend to have differing opinions about it. As I recall you think of symbolism primarily as a semiotic approach to the image. I agree that this is indeed a very limited notion of symbolism, tending to bypass the aesthetic being of the image in favor of disembodied concepts. But I rather see a symbol as a sacramental phenomenon, a theophanic event, a manifestation of the thing re-presented, unfolding inextricably within the nuances of the icon’s body. In the symbol we have the coming together of higher and lower ontological levels of reality, within the aesthetic being of the image. Doesn’t this understanding of symbol in a way parallel your notion of enargeia?

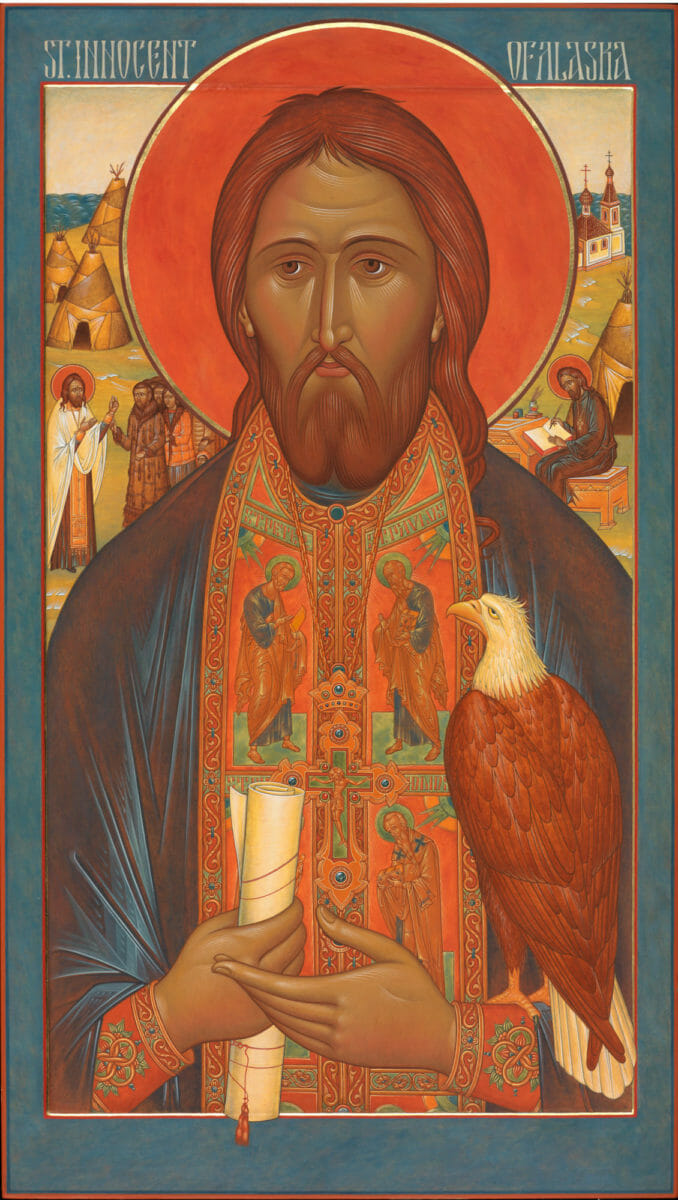

CT: This is a challenging and intriguing idea. I think enargeia has to do with the dynamics of form and that symbols, even though we may approach them as hybrids that combine visual and semiotic elements (the golden halo shows and signifies at the same time, a transcendent field and holiness or divinity respectively), always evoke a narrative. In other words, they point beyond themselves to a certain grammar and syntax that regulates their meaning—they implicate some non-iconic reality outside the image that authenticates them. It is true, on the other hand, that there can be a kind of synergy between the visual and semiotic, where the symbol subsists in the form, and the reverse, and that in some icons one can be drawn to that space (the way one may be drawn to Rothko’s color fields). It seems to me that if the external references that prompt us to “read” the image are minimized, and symbols participate in the aesthetic realities of the image, then we have the condition you are describing. What will it take to immanentize symbols in that way (to embed them strictly speaking in the “narrative” of the icon and only there) and what will such an icon look like? Take, for example, a bird that relates to some incident in the life of a saint or to his love of nature (such as your exceptional icon St. Innocent of Alaska (2012), where there seems to be a kind of conversation going on between the eagle and the saint). Based on what I am suggesting, the eagle’s place inside the icon must be liturgical rather than incidental. It must be totally at home there. Of course, whether what I am suggesting is doable or not is for the iconographer to determine. And I think that this is a good thing. That what one might propose from an aesthetic or theological point of view must pass through the iconographer and the icon and be tested that way.

Fr. Silouan Justiniano, St. Innocent of Alaska, 2012.

Egg tempera and gold on gessoed panel, 18 x 32 in.

Fr. S: In your most recent book, Tradition and Transformation in Christian Art: The Transcultural Icon, where the image of the King of Glory (Man of Sorrows) is explored, you bring Gadamer’s views on tradition and “horizon” into the conversation. In Icons in Time you mainly relied on V. Lossky’s understanding of tradition. How would you describe the compatibility of their respective perspectives? Can you tell us how you’ve synthesized their ideas on tradition in your study of the transcultural life of iconographic types?

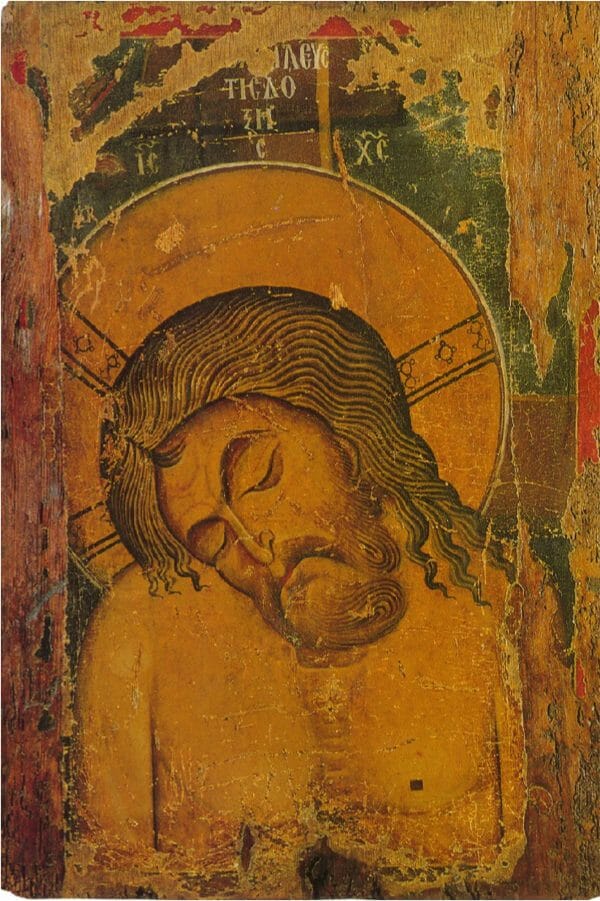

CT: I see Gadamer’s concept of tradition as an extension of what Lossky has written about the concept. If we approach tradition from Lossky’s perspective, as a hagiopneumatic reality, where what is created in the Church exists historically but also diachronically, in a modality of perpetual renewal and participation, then Gadamer’s “horizon” helps us map that process conceptually. Or, at least, it helps us outline the forms it may take. For instance, Gadamer’s understanding of tradition recalls the perichoretic movements that we associate with the mysteries of the Christian faith (the Incarnation, the Holy Trinity). He points out that works carry their own world to the present moment but also bring along the worlds that they accumulate as they pass through time. There is a sense here of the aura of a work extending beyond its immediate position or place toward the future and past and being present before us in that ontological abundance and liminality. I think Gadamer’s “horizon” is this plenitude of significations that surrounds a work and is never fully grasped by those that experience it. It seems to me that it is easy to bring these ideas to the hagiopneumatic view of tradition in Orthodoxy and to the practice of a traditional art form such as iconography. In Tradition and Transformation, for example, Gadamer’s “horizon” helped me think in terms of a “communion of icons” (koinonia eikonon) or to think of icons as living these interpenetrating lives across time. Think, for example, of all the variants of the King of Glory/Akra Tapeinosis since the type first appeared in the 12th century. Each one carries its putative original but does so in its own conditions and time. It is like a family or company of images that exist linearly and laterally at the same time. I found engaging Gadamer from an Orthodox perspective intriguing and constructive.

The King of Glory (bilateral icon, verso The Virgin Hodegetria), last quarter of 12th century, tempera on wood, Byzantine Museum, Kastoria

Roberto Oderisi, Man of Sorrows, c. 1354

Tempera and gold on panel, 24 1/2 x 14 14/16 in., frame: 27 x 16 7/8 x 1 13/16 in., Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum.

Niccolo Tommaso, Man of Sorrows, ca. 1370

Fresco transferred to canvas, Overall: 65x 70 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection.

Fr. S: You’re actually in the middle of working on a new book. What are you focusing on this time?

CT: The book is on The Neptic Icon and Postmodern Art. Its subtitle is New Orientations in Orthodox Theology and Aesthetics. Here, I add to the concept of enargeia that of nepsis, to characterize the icon that has a spiritual life. Neptic icons encompass eschatological moments in which the dualities and divisions of ordinary life are reconciled and transcended. The neptic icon is enargic. The study works critically with poststructuralist views of images and examples of postmodern art. It shows how these become relevant to the Orthodox icon (both in terms of similarities and differences), prompting new ways of thinking about icons that resonate with patristic theology. I focus on the writings of St. Gregory of Nyssa, St. Gregory Nazianzen, St. Maximos, St. Hesychios the Priest, and St. John of Damascus. Fluidity, openness, liminality become key concepts in rethinking or, I should say, rediscovering the icon and its theology.

Fr. S: Thank you so much Cornelia for your illuminating answers and taking the time to do this interview. I very much look forward towards getting my hands on your upcoming book.

Terms

Acheiropoietai: Greek for icons that have come into existence miraculously—not made by human hands.

Eusebeia: Greek for piety, reverence, respect, awe, and the act of showing these to a person or object.

Hagiopneumatic: Greek for “holy-spiritual,” or that which is informed by the Holy Spirit or in which the Holy Spirit is present.

Nepsis: Greek for sobriety, watchfulness, an attitude of attentiveness, alertness or vigilance.

Plerotic: Greek for that which fills, completes, or perfects, or the condition of being in such a state or being affected in that respect.

Ontophanic: manifesting being or the manifestation of the unique characteristics of a being.