Similar Posts

Divine Patters in Story and Image part 2:

The Iconographic Structure of St-Gregory of Nyssa’s Life of Moses

(This talk was given as the Climacus Conference, in Feb. 2017. Click here for audio and images)

St-Gregory of Nyssa has given us a jewel, the book we are looking at today, the Life of Moses is a very precious thing. In it, St-Gregory goes about “tracing in outline like a pattern of beauty the life of the great Moses.[1]” In giving us the life of Moses as a pattern for our own journey, St-Gregory is simultaneously using Moses as a guide to show us Christ, who lies at the summit of Moses’ journey and is the ultimate pattern as I discussed my last article. In between those two patterns, that is between the pattern for our own spiritual journey and the all encompassing pattern not made with hands, there exists many other patterns which are laid out by St-Gregory, patterns within patterns within patterns, creating a flexible but nonetheless solid mesh of connections which constitute a map of the world. Now when I say map of the world, I do not of course mean the same kind of map you get on your GPS, the map of the world is a map of meaning, to paraphrase Dr.Jordan Peterson, a map of how humans exist in the world, encounter the world and most importantly for us a Christians, a map of our movement on the ladder of divine ascent. And the pattern is already there, in the Bible, our traditions, our stories. Gregory is just pointing to it, pulling it out.

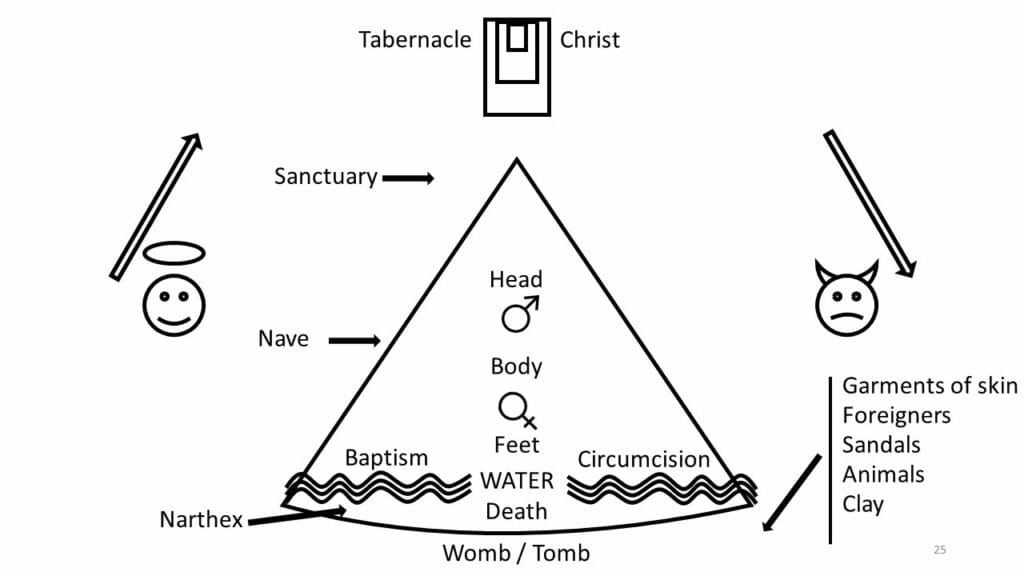

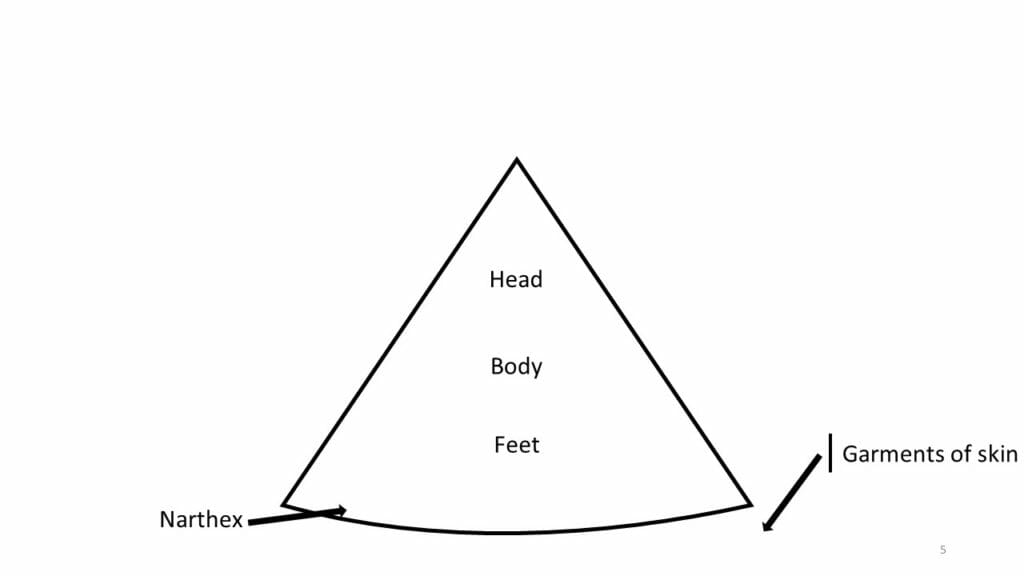

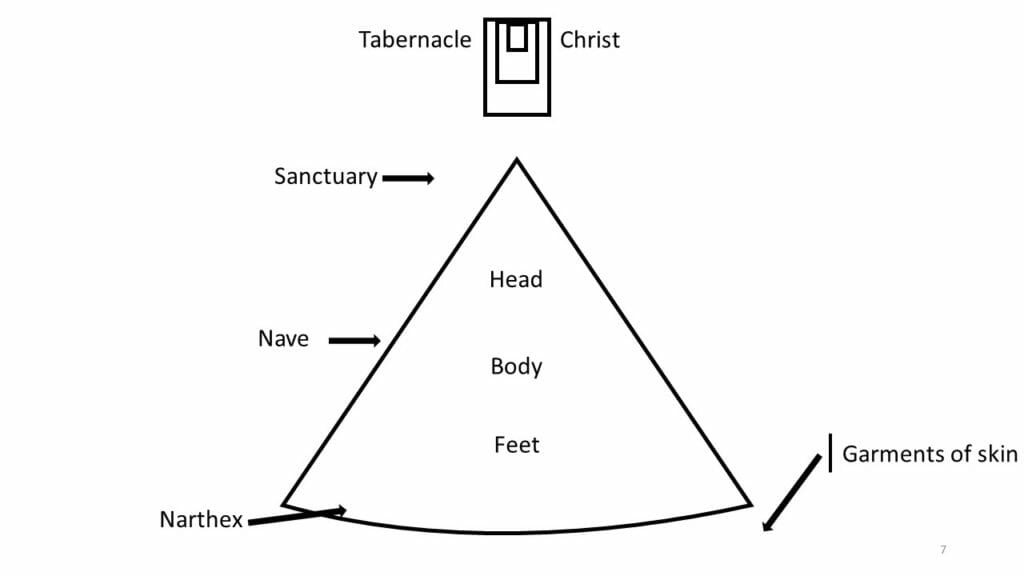

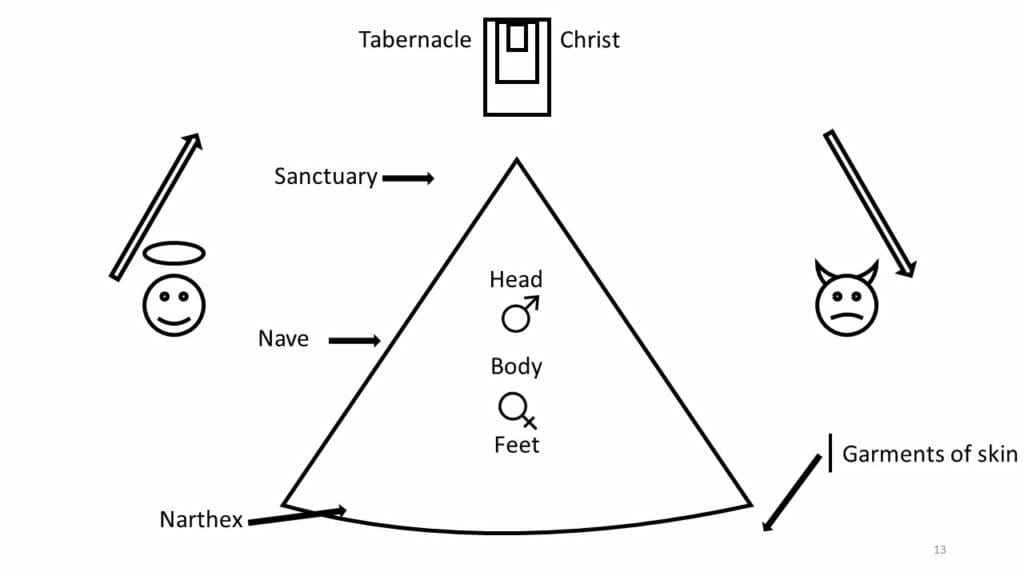

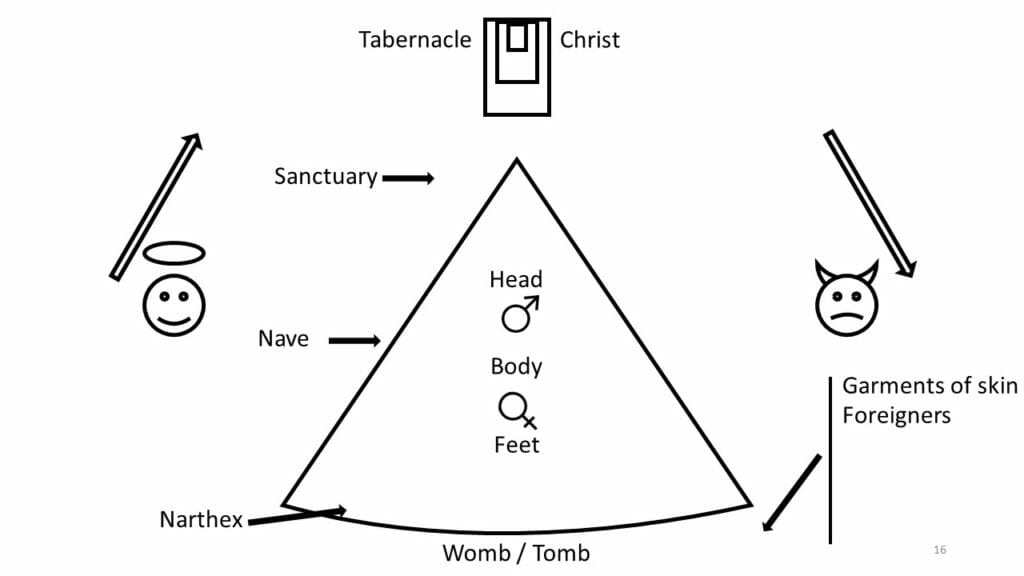

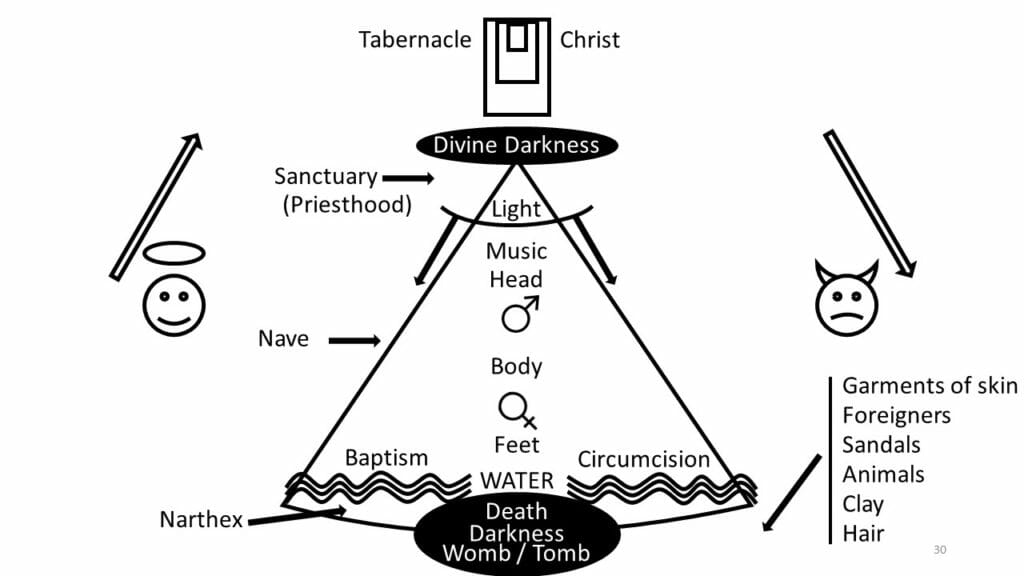

The basic motif in St-Gregory’s book is the ascent of Moses up the Sinai. Going up the mountain is the gradual ascent towards divinity, but it is also our entering and participation in the church.

The base of the mountain or rather what even precedes the base, is given to us in images of flesh relating to all that is outside of our nature, all that is foreign to us, the garments of skin which were given to Adam and Eve at the fall. The base is the narthex, let us say, the place where the Church ends and the “World” begins. The bottom of the mountain is also the “feet of the soul” the passionate and appetitive parts of the soul.

The top of the mountain, which is the place of encounter with God is the intellect, the higher part of the soul where we can grasp the nature of all things. It it is also the sanctuary of the Church, and then beyond that, beyond the most inner and highest place of our being, we can enter the divine tabernacle which is Christ himself, the head of the body.

What has just been described is the basic pattern which joins the personal to the communal and ultimately to the spiritual and uncreated. Today I want to lay out for you how things come together, what exactly these patterns look like and how they appear to us. As you can see by looking at the diagrams I am inserting into the text, I use St-Gregory’s words to build a spatial map so to help us see how things fit together.

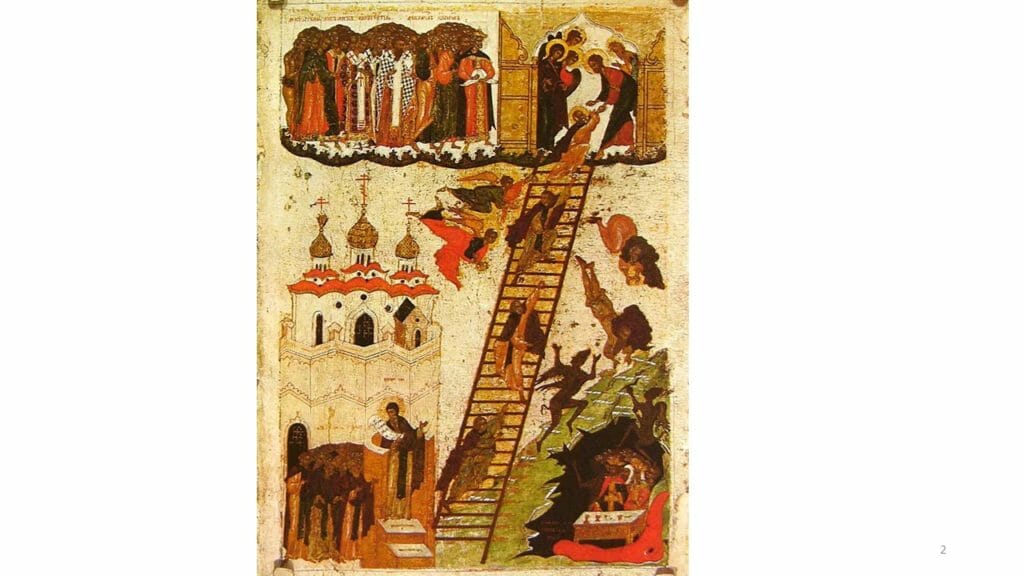

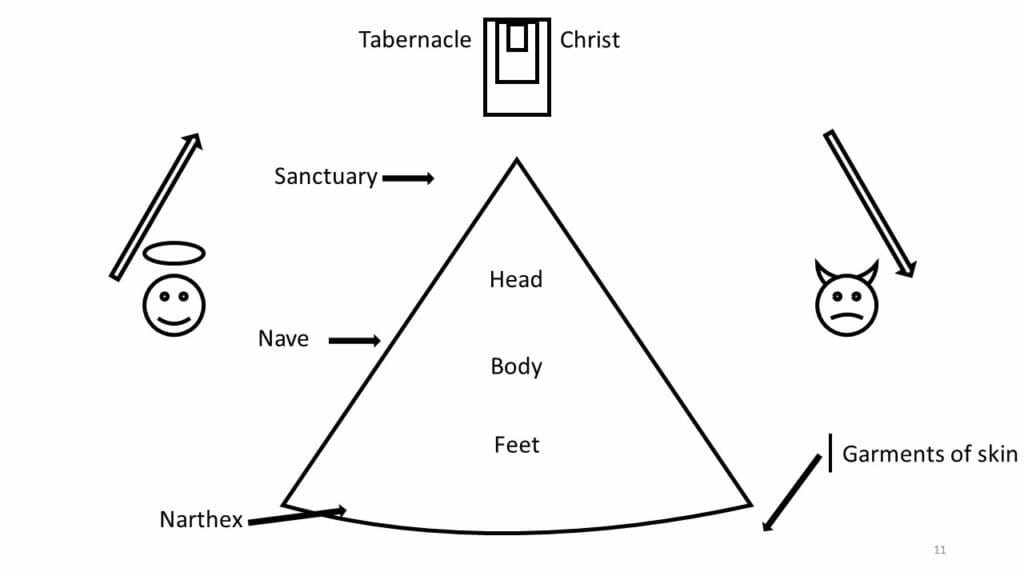

One of the crucial aspects of symbolism and patterns is that the elements of a pattern are neither good nor bad in themselves, they are “places” of meaning. What is important is not so much where something is on the map of meaning, but rather what direction it is facing and what purpose it has in facing that direction. Each symbol can have a light and a dark side, if you will. The clearest vision of how each image in a symbolic pattern has two sides is in St-Gregory’s account of Aaaron, Moses’ brother. Aaron was chosen by God to be Moses’s helper, and what St-Gregory interprets in this is that Aaron is analogous to our guardian angel, the angel God places with us to council us, to entice us in making our ascent to the divine, doing this through reasonable thoughts and encouragement. But for those who know the story, Aaron is also the one who made the golden calf and brought Israel to engage in licentiousness and idolatry. So how do we reconcile that? Well Gregory tells us a secret. He tells us that :

There is a doctrine (which derives its trustworthiness from the tradition of the fathers) which says that after our nature fell into sin God did not disregard our fall and withhold his providence. No, on the one hand, he appointed an angel with an incorporeal nature to help in the life of each person and, on the other hand, he also appointed the corruptor who, by an evil and maleficent demon, afflicts the life of man and contrives against our nature. (Book II. Par.45)

Ok, so what are we talking about? Most of us know what he is referring to here. It is referring to this:

The faster we make our peace with this the better. The imagery might seem silly, but only if we are materialists who think that angels are actually fleshy people with wings or that devils have spiky tails. Once we get rid of the materialist blindfold we often have, we experience this every day of our lives. Anyone who has ever fought a passion, or else given into a passion and then suddenly “woken” up in regret will know that this fight inside us is happening all the time! If the reader is struggling with an image of Donald Duck fighting his inner angel and demon, I have already showed you the icon version of that, it is the Ladder of Divine Ascent. And so the brother, who is our counselor, or let’s us call it that little voice in our head, our conscience, whatever, can be become the angel or the demon, depending on which side the person decides to go, which way a person decides to move.

I will start describing the journey at the beginning of Moses’ life, when he is still at the bottom of the mountain, so to speak. In discussing the birth of Moses and the rule given by pharaoh according to which the male children of the Israelites were to be killed, he says that

For the material and passionate disposition to which human nature is carried when it falls is the female form of life, whose birth is favored by the tyrant. The austerity and intensity of virtue is the male birth, which is hostile to the tyrant and suspected of insurrection against his rule. (Book II, par. 2)

So we’ve got Materiality and passion related to the female, and austerity and virtue relate to the male. Right away, our modern minds are bothered by this, and that’s understandable. But hold that thought. You see, already hiding in this quote, we discover the dark side of the masculine, that is the tyrant. Things will balance out.

Gregory starts the story relating that Moses had two mothers. In order to protect the baby Moses from being killed by Pharaoh, he is placed in a basket on the Nile, which is found by an Egyptian princess. St-Gregory tells us

“that the daughter of the king, being childless and barren (I think she is rightly perceived as profane philosophy), arranged to be called his mother by adopting the youngster… … For truly barren is profane education”(Book II, par. 10)

The adoptive mother is the knowledge of the world, profane and natural philosophy, which St-Gregory warns can sometimes impede our spiritual journey. This is the foreign princess. As for Moses’ s birthmother who continued to care for him as he was being raised by the Egyptian, Gregory tells us that she is the Church and its teaching. So already we start to see the other side of the feminine appearing.

The feminine is the periphery in the sense of the womb, that which surrounds us, but at the risk of delving into clichés, it is both the womb and the tomb if you will. St-Gregory uses rather the image of the fruitful womb opposed to the “womb of barren wisdom“(Book II, par. 11) so both the Church which contains us and the outer world which is dissipation.

In terms of what is foreign, the idea that Gregory develops is that the subjugation of the Israelites to the Egyptians in the book of Exodus is an image of the subjugation of the human person to what is “added” or exterior to our nature, the tyranny of our flesh, our desires. Throughout the text, the Egyptian or all the foreign nations in the story are interpreted as those foreign elements which entrap us, and then pursue us when we try to flee from them. For example, when Moses grows up, he suddenly feels an attachment to Hebrews, his own people, who are slaves in Egypt. One day Moses kills an Egyptian who he sees abusing an Israelite.

Moses teaches us by his own example to take our stand with virtue as with a kinsman and to kill virtue’s adversary. The victory of true religion is the death and destruction of idolatry. (Book II, par. 15)

The slavery to the foreign elements, idolatry being the best example, can appear as a form of tyranny but it can also appear as seduction. In the story of Moses, foreign women seduce the Israelites and bring idolatry with them, so that even after fighting and escaping foreign tyrants, they fall back through seduction: ”it was only to be expected that some among them would be filled with lust for unlawful intercourse with foreigners.“ (Book II, par. 299)

So the foreign women are idolatry, that is the slavery to our passions, they are also the barren profane philosophy. But you see, there is a trick in this, because Moses also had a foreign wife, and so the duality of that symbolism begins to occur.

The foreign wife will follow him, for there are certain things derived from profane education which should not be rejected when we propose to give birth to virtue. 56 Indeed moral and natural philosophy may become at certain times a comrade, friend, and companion of life to the higher way, provided that the offspring of this union introduce nothing of a foreign defilement. (Book II, par. 37)

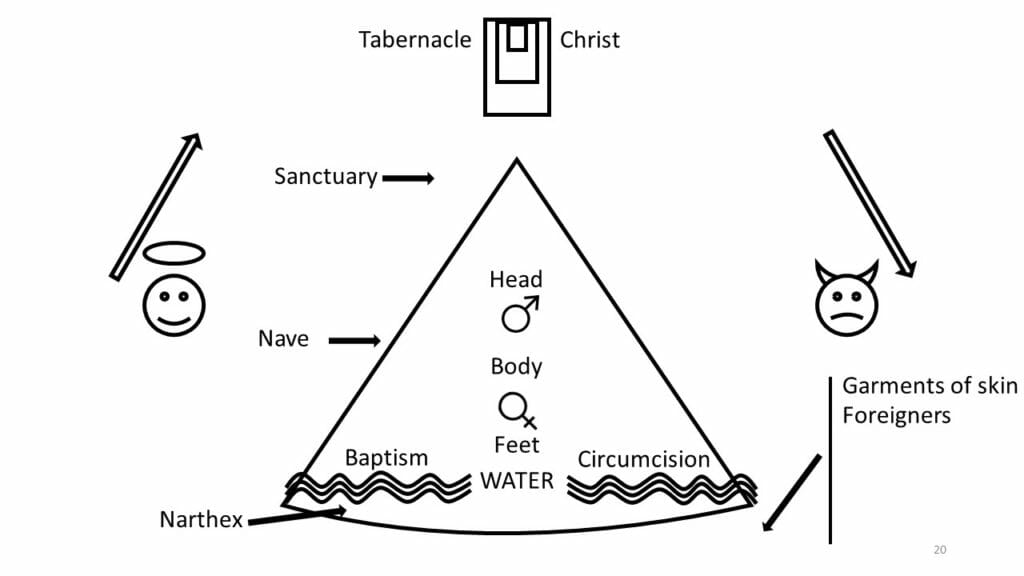

And Moses’s wife is the one who circumcised Moses’s son. Circumcision is the cutting off of the garments of skin, the foreskin is removed as the mark of the foreigner.

Since his son had not been circumcised so as to cut off completely everything hurtful and impure, …His wife appeased the angel when she presented her offspring as pure by completely removing that mark by which the foreigner was known. (Book II, par. 38)

Gregory beautifully weaves in the image of circumcision in with the notion of baptism, if the foreign is removed by the foreign wife, so too in baptism death is removed by death. So down there, one could say, between the foreign tyranny and the mountain, there is that water which is also death, and one must go through the waters in order to begin the journey. Of course for St-Gregory, the crossing of the Red sea is exactly that, our baptism which commences our journey. Moses split the waters and crossed the Red Sea, pursued by Egyptians on whom the waters closed, “after we have drowned the whole Egyptian person (that is every form of evil) in the saving baptism we emerge alone, dragging along nothing foreign in our subsequent life.” (Book II, par. 126)

Related to all this, the garments of skin, that is our outer fleshy part are called “dead and earthly” (Book II, par. 22), they are related to our animal aspect. For example at the point when Moses comes back down from the mountain, St-Gregory makes a big deal to the fact that animals, as described in Exodus, should not even touch the base of the mountain. He says “That none of the irrational animals was allowed to appear on the mountain signifies, in my opinion, that in the contemplation of the intelligibles we surpass the knowledge which originates with the senses.” (Book II, par. 156)

The removal of the Garments of Skin appear strongest when Moses ascends to encounter the burning bush. Moses is asked by God to remove his sandals in order to approach the vision. St-Gregory relates the removal of the sandals to the removal of the garments of skin “ Sandaled feet cannot ascend that height where the light of truth is seen, but the dead and earthly covering of skins, which was placed around our nature at the beginning … must be removed from the feet of the soul.” (Book II, par. 22) But even this removal finds a surprising duality. When Gregory describes the burning bush, he insists on the notion that the bush was a thorn bush. Now why would he insist on the thorns?

Moses on that occasion attained to this knowledge (of True Being), so now does everyone who, like him, divests himself of the earthly covering and looks to the light shining from the bramble bush., that is, to the Radiance which shines upon us through this thorny flesh and which is (as the Gospel says) the true light and the truth itself. (Book II, par. 26)

One must ponder on that quote for a moment. In the book of Genesis, one of the consequences of the fall of Adam and Eve is that creation will produce thorns, and the garments of skin God gives to Adam an Eve are meant to protect them from the consequences of the fall of which thorns are the physical image. But here, just as Moses removes the outer fleshly covering of skin, the consequence of the fall, he experiences the light shining through the thorn bush, through the thorny flesh.

All of this question of periphery is resumed in the notion Gregory uses of clay. He connects the slavery of the Israelites in this foreign land to what they are doing, that is being forced by the foreigner to make bricks out of clay.

For this demon who does men harm and corrupts them is intensely concerned that his subjects not look to heaven but that they stoop to earth and make bricks within themselves out of the clay.(Book II, par. 59)

We need to understand this clay as a kind of half-formed element, confusion and ambiguity. St-Gregory relates the unformed clay to the frogs which come out to plague the egyptians, frogs being amphibian in nature and so a hybrid creature which exists between land and water.

The examples of periphery I have mentioned, if one only takes a moment to think about it are simply how we experience the world: The feminine as the womb, the house which contains us as either the church or the world — the foreigner whom we encounter as that which comes from the other side of the border — the passions which make us idolaters and dissipate us to the outside — the animal which is body or flesh without reason — clay, that ambiguity and confusion that comes when the order of the center cannot hold. All of these examples are how we personally experience periphery and this periphery has a dual nature depending on its being turned towards or away from the center.

Moses goes up the mountain and let us be clear, the movement up the mountain is characterized by a type of divesting, the removal of the sandals, the purification from the “attachment” to peripheral things. There is also rarefication, where the “mass” of people stay at the bottom and Moses rises alone, somewhat like the high priest who alone can enter into the holy of holies, and this echoes the shape of the mountain itself, which is large at the base and moves up to a narrower summit.

Moses goes up the mountain and let us be clear, the movement up the mountain is characterized by a type of divesting, the removal of the sandals, the purification from the “attachment” to peripheral things. There is also rarefication, where the “mass” of people stay at the bottom and Moses rises alone, somewhat like the high priest who alone can enter into the holy of holies, and this echoes the shape of the mountain itself, which is large at the base and moves up to a narrower summit.

The movement up the mountain is the movement up the pattern of meaning itself, up the epistemological and ontological hierarchy of beings. St-Gregory explains how the ascent of the mountain is Moses’s discovery of real knowledge of being (see Book II, par. 23-25), by removing the sandals and seeing the light in the bramble bush he is moving away from dependent beings. What is meant here by dependent beings is basically everything. Any created thing when isolated from its relationship to God, appears as types of falsehood, and so Moses is moving towards Being in itself, from which dependent beings find their meaning and coherence. This movement towards Being is analogous to the movement up from the multiplicity of the base of the mountain, into the unity of the summit.

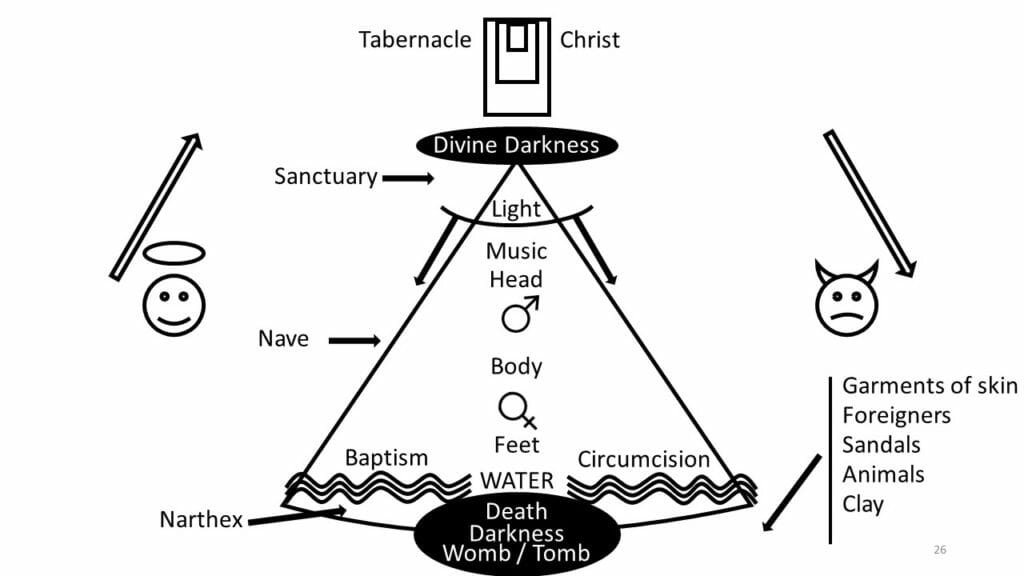

The bottom of the mountain is assimilated to darkness, and as Moses goes up he encounters light and music, the sources of visual and auditory meaning, but to enter the divine chamber, the sanctuary, Moses must encounter God in the higher darkness.

What does it mean that Moses entered the darkness and then saw God in it? What is now recounted seems somehow to be contradictory to the first theophany, for then the Divine was beheld in light but now he is seen in darkness. Let us not think that this is at variance with the sequence of things we have contemplated spiritually. Scripture teaches by this that religious knowledge comes at first to those who receive it as light. Therefore what is perceived to be contrary to religion is darkness, and the escape from darkness comes about when one participates in light. But as the mind progresses and, through an ever greater and more perfect diligence, comes to apprehend reality, as it approaches more nearly to contemplation, it sees more clearly what of the divine nature is uncontemplated. (Book II, par. 162)

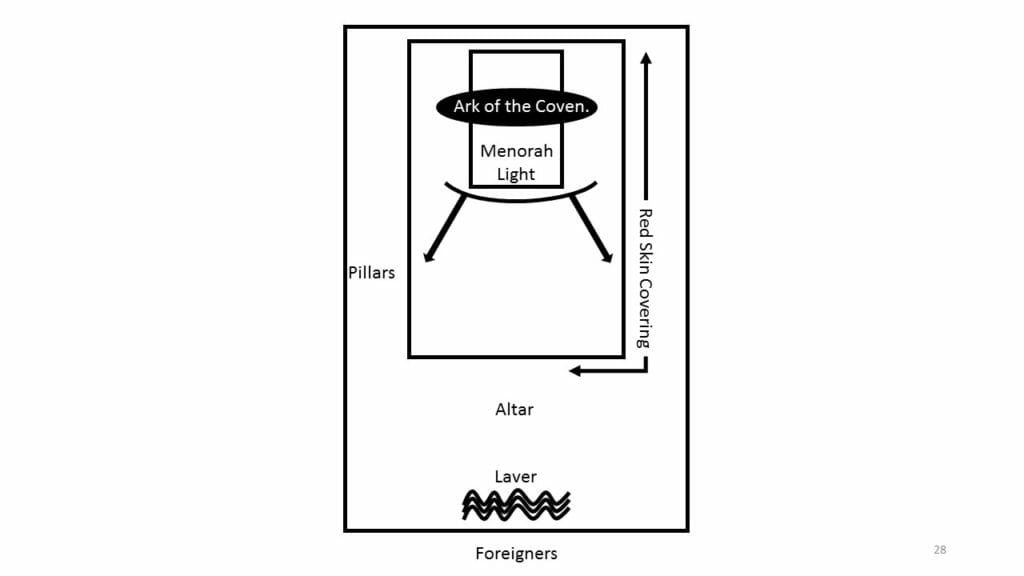

As I explained in my last article, beyond the darkness, Moses encounters the pattern of the tabernacle. The pattern of the tabernacle is fascinating because in its description, we could stretch it out and encompass everything else within it, that is it repeats the whole map we have already looked at. In moving out of the world so to speak, Moses regains the world. So for example in its most hidden place, the tabernacle is equivalent to the lonely place of Moses’s encounter with God, the menorah, the seven branch candlehoder is made equivalent to the rays of the spirit and the pillars of the tabernacle are the pillars of the church “all those who themselves support the Church and become lights through their own works are called “pillars” and “lights.” (Ibid. Book II, par. 184)

“You are the light of the world, says the Lord to the Apostles” (Book II, par. 184) This light is the very light encountered by Moses as he ascended. Finally on the edge of tabernacle, the outer cover or the tabernacle which was made of animal skins which were died red, and so the beauty is that in the tabernacle, just like in the burning bush, the dead skins which were removed in the ascent are found again, though transformed. What were the enslaving passions are now the Passion of Christ,

“Even if one sees skin dyed red and hair woven, the sequence of contemplation is not broken in this way. For the prophetic eye, attaining to a vision of divine things, will see the saving Passion there predetermined. It is signified in both of the elements mentioned: the redness pointing to blood and the hair to death.” (Book II, par. 183)

Gregory tells us that “Hair on the body has no feeling; hence it is rightly a symbol of death.“ (Book II, par. 183)

One of the things that is encountered by Moses in the heavenly tabernacle is the pattern of priesthood which is given to Moses. This makes the mountain also analogical to the Ecclesiastical hierarchy which is elaborated in Dyonisian theology, but in that section, Gregory also traces for us the shadow of the ascent, he speaks of a false ascent, the ascent of pride which can bring men to gain the priesthood for themselves in order to bolster their own position, and so the passions of licentiousness which are seen as a wallowing in mire at the bottom of mountain find their pair in the mock ascent accomplished in pride (see Book II, par. 278-283). So everything, even the ascent has a light and a dark side.

Now I’ve only brushed the surface of what Gregory deals with, I encourage all of you to explore the book on your own and discover the wealth if offers. But if we look at our map here projected, I think we have enough elements to get a sense what this is about. So please look at it carefully, we have the feminine which is mother, education and the church or else it is profane knowledge, the world.

We find the foreigner who is the tyranny of idolatry, but also the profane knowledge which can become our wife and friend as we move forward. We have animality which are our passions and should be removed but they can also be transfigured. We have this process of purification, water, fire, baptism or circumcision. We have the masculine which in Moses is the virtuous individual but it can also be the tyrant, the pharaoh. We see the brother/angel who is a counselor for good on one side or for evil on the other.

We find the true ascent towards divinity and the priesthood, and the false ascent which is the fruit of pride.. And finally we find the darkness which his encountered at the bottom and at the top of the mountain with light and music in the middle. And above it all, there is the divine tabernacle which is Christ and which even beyond the unknowablity of divinity, paradoxically resolves all the dualities, gathers all things into himself, unites all the opposites and is simply all in all.

Now try to keep the basic pattern in your memory. It should not be so difficult, because in theory the elements are intuitive and should make sense to us on a very basic level. The pattern will then repeat itself. Watch.

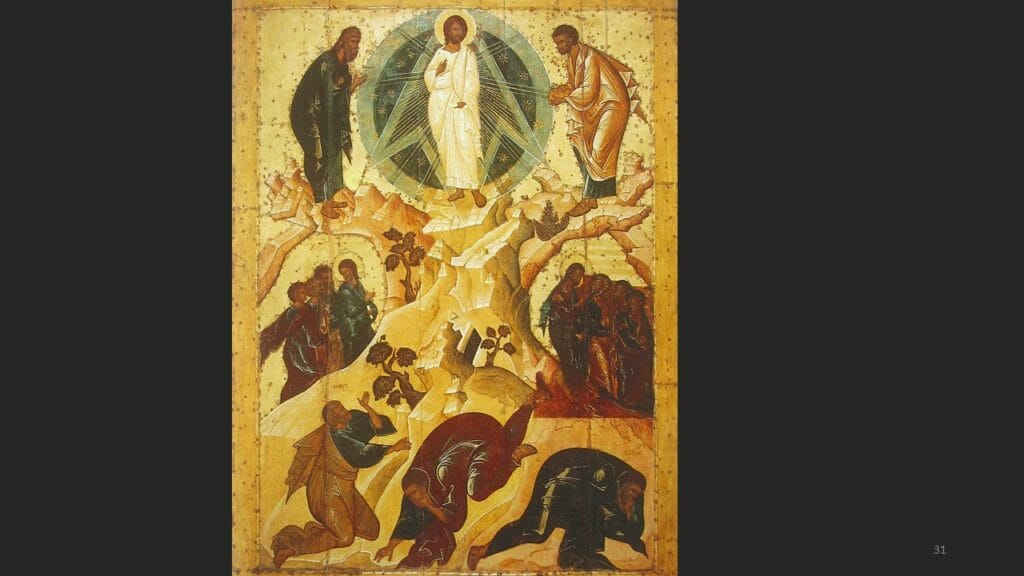

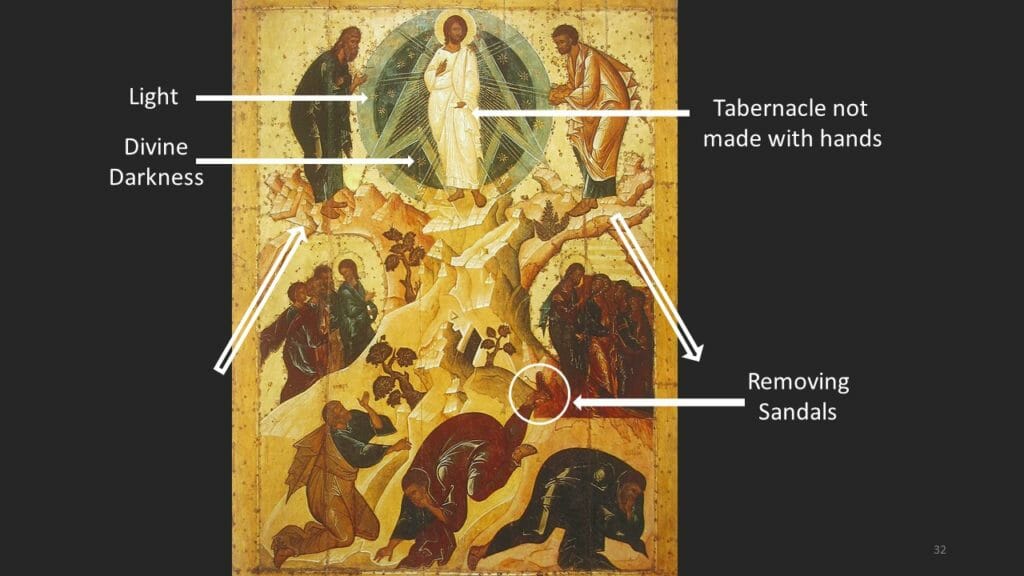

Can you see the pattern?

Let me help a bit.

Atop the mountain, the glory of Christ is composed of an outer light and an inner darkness. Christ in the center, beyond the darkness, is the Tabernacle not made with hands. We see St-John losing his sandals. The Disciples ascend on one side and descend on the other. Here we can see the positive side of the descent of the mountain which I have not yet mentioned. We can be descending the mountain as a kind of fall, but we can also be descending the mountain in order to bring to others what we encountered there as Moses descended to bring the Law to the Isrealites. Here is another:

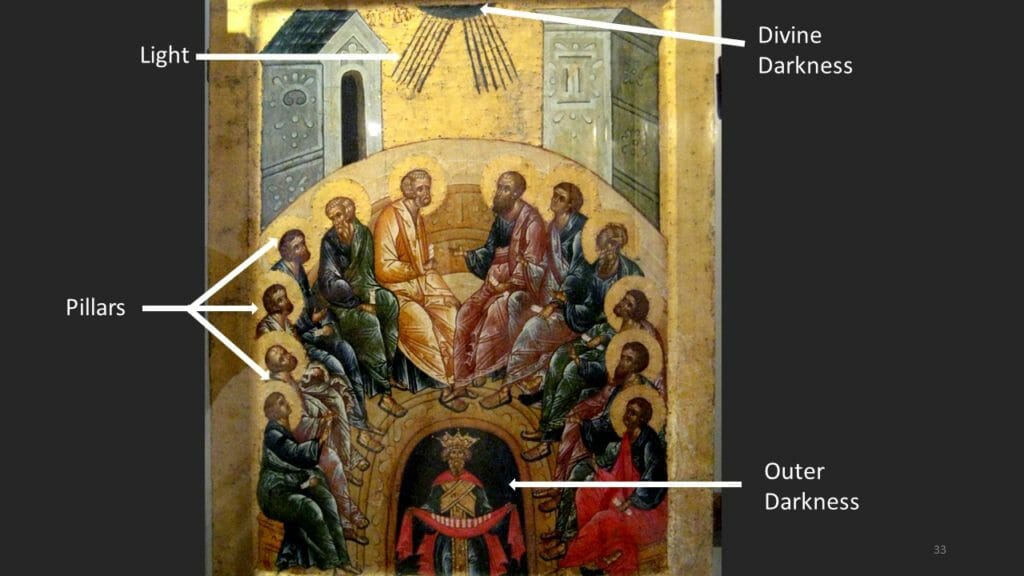

Can you see the pattern?

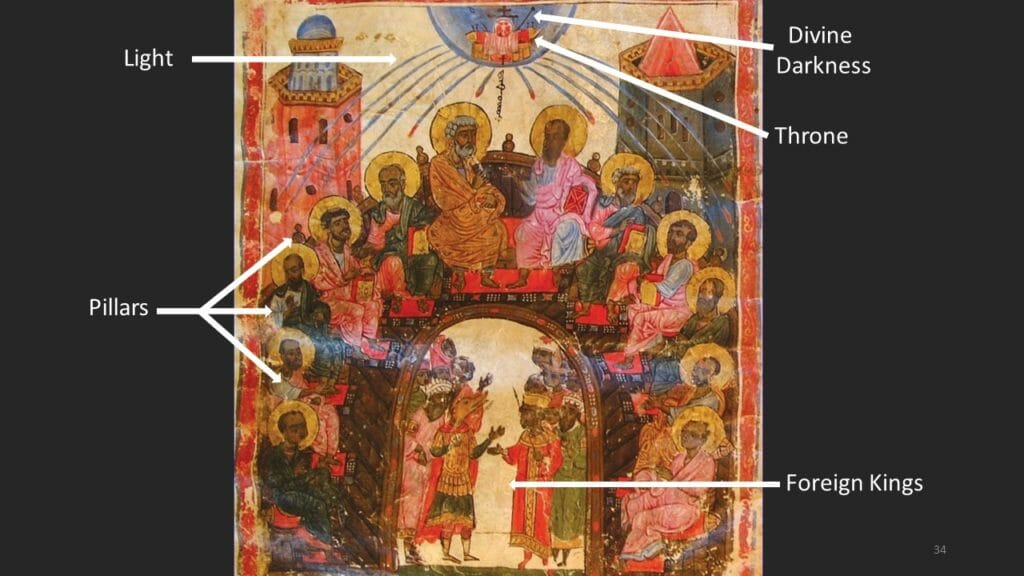

The Pentecost icon is the image of the foundation of the Church. Atop the icon is the divine darkness with light rays coming down. The disciples are the pillars of the Church. And down below in the door going outside is the outer darkness where the old king Cosmos stands. In older images it was not King Cosmos who stood in the outer darkness, but rather it was a crowd of foreigners. And often, especially in Syriac images, one of the foreigners was a dog-headed man, that monster, that frog which shows us the limit of the world. It is a positive move from the unity of Christ into the multiplicity of the world.

And if we think of the inverted version of the Pentecost image, that is the tower of Babel, we have the same structure: men using bricks made out clay to build a false ascent, an ascent of pride towards God. And what is the result of this? The creation of foreigners. It is a negative movement from the unity of one language into the fragmentation of chaos.

Can you see the pattern?

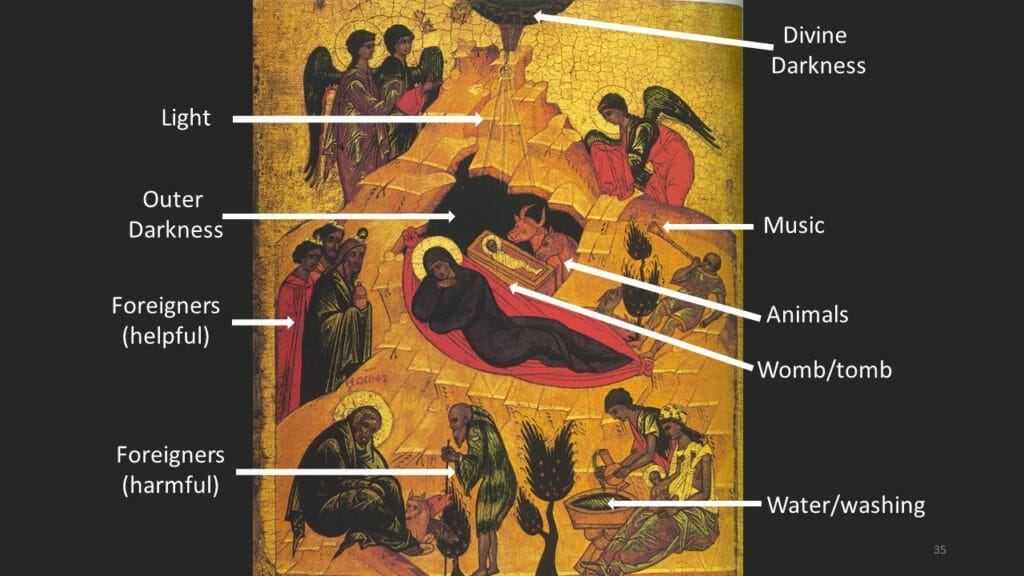

In the icon of the Nativity, we do not have a descent of the mountain, but a descent into the mountain. Of course it is not difficult to see that these are the same thing, for in the cave we find the womb and the tomb, the tomb being represented by the manger. We also find animals inside the cave. There is the positive foreigner, the Magi coming to serve Christ, and the negative foreigner, the demon/shepherd coming to tempt st-Joseph. Finally we even have a bathing scene at the bottom of the image.

One more.

Can you see the pattern?

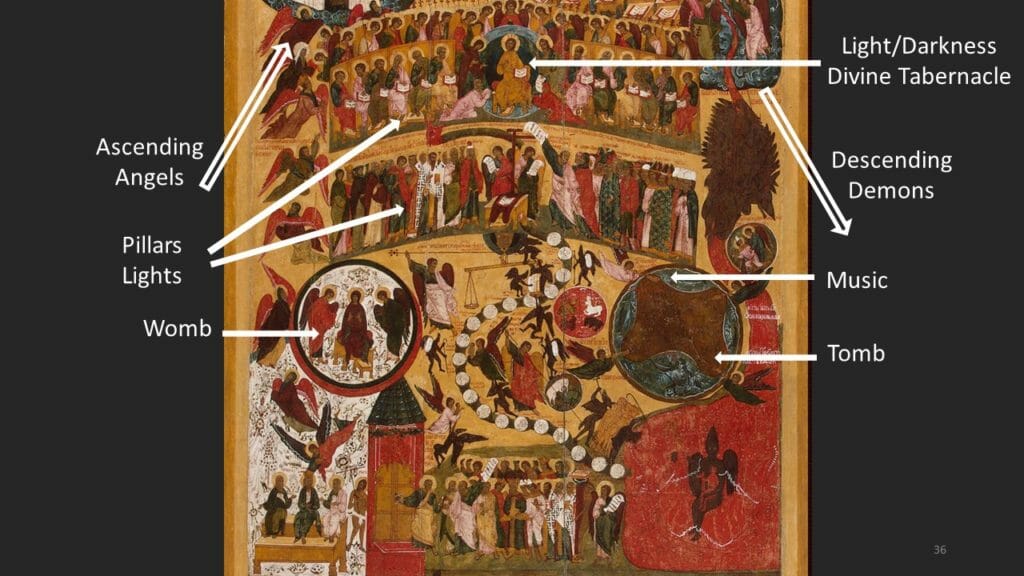

Christ is in his glory made of inner darkness and outer light. The saints are organized as hierarchy of pillars, a cosmic architecture, a cosmic ladder. The angels ascend on one side, the demons fall on the other. And in this version of the Last Judgement, there is amazing structure, for on one side of the lower tier of the icon is represented the earthly paradise in a circle, symbolized by the Theotokos, the womb, the mother of all, and on the other side is represented death. The other circle with a chaotic shape inside is an image of the dead coming out of their tombs to be judged. And what is calling them out of the tombs, music, the sound of trumpets which Moses heard as he ascended the mountain?

I could go on and on with several other images, and I encourage the reader to find other examples of how the structure found in the story of Moses and detailed by St-Gregory acts as a cosmic map, a map that not only shows us the shape of the world, but traces the way to Christ, the divine tabernacle not made with hands, who is all at once the origin and fulfillment of creation.

——————————————–

[1] St-Gregory of Nyssa, “Life of Moses”, Book II. Par.319. Translated by Abraham Malherbe. Paulist Press, New York. 1978 (All other citation references in the text.)

Thank you for this cogent explanation. I am not of the Orthodox tradition and have never understood how to read an icon. They are so beautiful and this is extremely helpful. Thank you so much.

This is fantastic, thank you!