Similar Posts

____________________________________________________________

Editorial note: We have convinced Aidan Hart to post a chapter from his new book. “Techniques of Icon and Wall Painting” which is being hailed as the most comprehensive book to date on practicing the art of Iconography. At 450 pages, with 460 paintings, 150 drawings and covering everything from theology and design to gilding and varnishing, it is a prized possession for anyone interested in the traditional arts. The chapter being serialized over the next weeks is called “Designing Icons”. You will see why Archimandrate Vasileos of Iviron called this book the “Confessio of a man who epitomizes the liturgical beauty of the Orthodox Church”. More details about the book on Aidan’s website.

Editorial note: We have convinced Aidan Hart to post a chapter from his new book. “Techniques of Icon and Wall Painting” which is being hailed as the most comprehensive book to date on practicing the art of Iconography. At 450 pages, with 460 paintings, 150 drawings and covering everything from theology and design to gilding and varnishing, it is a prized possession for anyone interested in the traditional arts. The chapter being serialized over the next weeks is called “Designing Icons”. You will see why Archimandrate Vasileos of Iviron called this book the “Confessio of a man who epitomizes the liturgical beauty of the Orthodox Church”. More details about the book on Aidan’s website.

____________________________________________________________

This is part 5 of a series. Part 1, Part 2 , Part 3, Part 4 (In this section, Aidan give explains the basic elements and conventions of icons.)

Now that you have amassed the various elements of the tradition surrounding the icon subject (See previous posts), it is time to select what is to be emphasized and then prepare the design itself.

In the case of a saint’s icon, you will need to pare things down by selecting the features of their character and life that the icon is going to concentrate on, and then find ways of expressing these. What you select is often influenced or requested by the client. It goes without saying that whatever is chosen must be truthful. Though there need not be a spirit of fear, on the other hand there is no room in the tradition of sacred iconography for arbitrary experiment. As Leonid Ouspensky writes in his Meaning of the Icon:

An icon cannot be invented. Only those who know from personal experience the state it portrays can create images corresponding to it, which are truly ‘a revelation and evidence of things hidden’ (St. John of Damascus)…[1]

And the Fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council who defended the icon tradition against the iconoclasts, stated:

The making of icons does not depend upon the invention of painters, but expresses the approved legislation and tradition of the catholic Church…

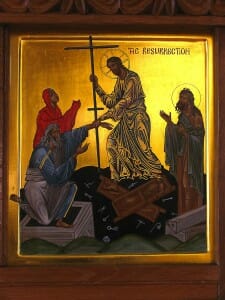

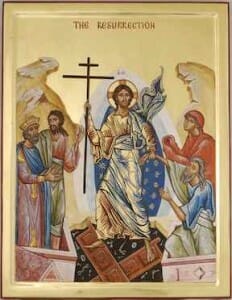

In the case of a festal icon, the general arrangement of figures is already well established. But there is nevertheless legitimate variety within these parameters, as is clearly evident from a perusal of different icons of a given feast

Once you have chosen the main themes it is time to start developing ideas for the design proper. This is a time to brainstorm. What you write down does not have to be used, so treat this as a way to draw out ideas. On one side of a piece of paper I write down the things to convey about the saint or event, and on the other side jot down possible ways of expressing these formally.

One can adapt an existing icon, fuse together elements from a variety, or even, when no icon of a saint exists, design a new one. This design stage will be easier as you gain more experience of the tradition and accumulate a vocabulary of stylistic means. Below are discussed various elements of the icon tradition and some principles of design.

Conventions

Some details like the saint’s type – martyr, cleric, prophet etc. – are readily illustrated by formal means. The tradition offers a rich vocabulary here. Below is given a range of such conventions that are often, though not exclusively used:

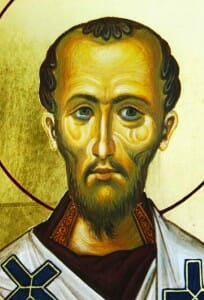

Teachers. Often shown with high temples, sometimes with a scroll bearing their words

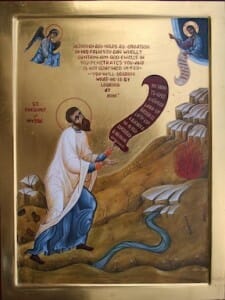

Prophets. Often depicted holding an open scroll bearing one of their prophecies.

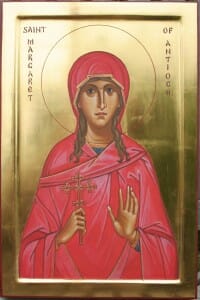

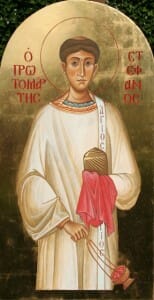

Martyrs. They almost always are shown holding a cross in their right hand and with the colour vermilion in their garment

Sometimes instruments of their martyrdom are included, such as St. Sebastian with arrows, St. Lawrence with the gridiron, or St. Catherine with her wheel. However, these elements if included should direct our attention to and not distract from the saints themselves. There was a tendency in later Western painting and in decadent iconography to overload the image with such symbols or instruments of martyrdom.

Monastics. Monastics’ garments are usually painted in earth pigments to reflect their poverty

Common colours are green earth, red ochre, orange ochre, yellow ochre, raw umber, and Indian red (caput mortuum).

Royalty and aristocracy. These are robed in fine, bejewelled garments, often employing complementary colours like red and green, and also a bright yellow ochre to create a joyful and rich effect .

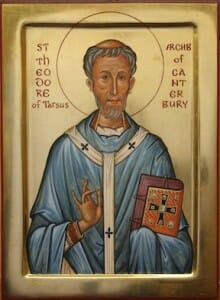

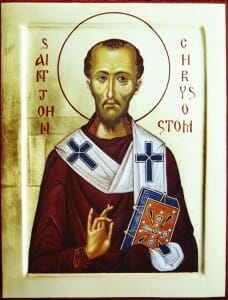

Bishop or priest. They are shown holding the Scriptures in their left hand and blessing with their right, and usually, though not exclusively, in their liturgical vestments. For eastern bishops this will always include the omorphorion.

Deacons. They usually hold a censer in their right hand, and in early icons in their left hand they hold a treasure box containing the alms that they are charged to distribute among the needy.

In later icons this box tends to be replaced by the liturgical incense boat, containing extra incense. Deacons are usually shown in the white dalmatic (or sticharion to use the Orthodox Church’s term).

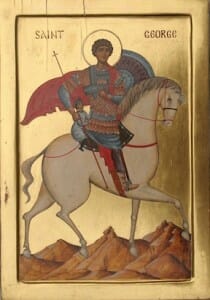

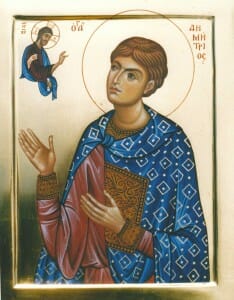

Soldier martyrs (e.g. St. George, St. Demetrius). They are painted either in their military armour, or if for a deisis tier, in robes.

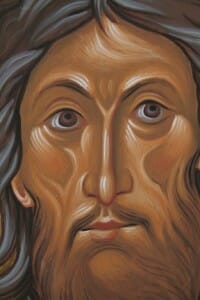

Ascetics. They have drawn faces, with strong lines and modelling around the cheekbones to reflect their life of fasting and sobriety. Here the painter needs to balance this gauntness with gentleness and nobility of expression, otherwise such faces can easily look harsh.

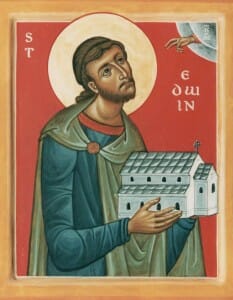

Church founders. These are frequently shown holding a schematized model of the church or monastery building in question, sometimes offering this to Christ.

The same scheme can be used to symbolize a saint’s apostolic ministry, where church communities are founded rather than buildings.

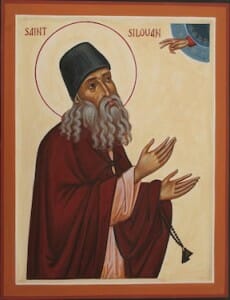

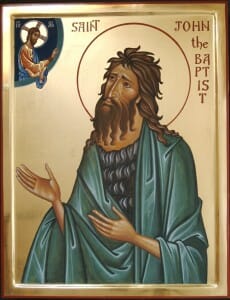

Deisis. Icons of saints interceding before Christ (deisis) characteristically have them with both hands raised in supplication (see fig. above of St. Silouan)

or sometimes just one. If they are soldier martyrs like George or Dimitrios, they are not dressed in their armour but in robes. This is because the emphasis in the deisis is on the saints’ glorified state in heaven as intercessors for the world, rather than on details of their earthly life.

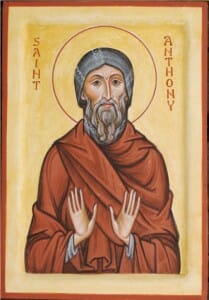

Prayer gesture. Saints who havedevoted their life to prayer, such as the desert ascetics, are often shown with their hands faced out in a gesture of prayer and witness

[1] The Meaning of Icons, page 42.

[…] Dec 17th 9:46 pmclick to expand…Designing Icons (pt.5): Conventions of Traditional Icon Design https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/designing-icons-pt-5-conventions-of-traditional-icon-design/Tuesday, Dec 18th 8:49 amclick to expand…Response to Newtown: Even in the face of horror, there is […]