Similar Posts

Archetype and Symbol II:

On Noetic Vision

Upon reading the article Archetype and Symbol: Thoughts on the Creative Act, my friend wrote asking me to clarify a few things. The following article qualifies the term “ noetic vision of archetypes,” re-examines the notion of “abstracting the universal from the particulars,” and expands on the role of the geometric in iconographic representation.

Dear C.,

I should begin by a clarification of the term, “noetic vision of archetypes.” The term “noetic vision” might be confused with the notion of contemplation, a word that has to be interpreted in context and which tends to conjure up so many vague ideas that it becomes almost meaningless. Lets look at some definitions.

The state of contemplation (theoria), as described by the fathers of the Philokalia, is a perception or vision of the nous (intellect), through which spiritual knowledge is obtained; it is not of our own doing, but is granted by grace to the pure of heart. Contemplation in this sense is usually divided into two main stages: vision of the inner principles (logoi/archetypes), or hidden nature of created beings, and theology proper, the vision of God.[i] Origen gives as an example of the first stage Isaac, who is, “an exponent of natural philosophy, when he digs wells and searches out the root of things.”[ii] He sees the second stage exemplified in Moses, who entered the dark cloud and beheld the burning bush, Paul, who in ecstasy saw the third heaven, and St. John the theologian who leaned on the Lord’s bosom and received the Revelation.[iii]

Contemplation presupposes praxis, the active life of virtue, nepsis or watchfulness, repentance, purification from the passions, perfection of Christian love and requires detachment. As Ilias the Presbyter says in his Gnomic Anthology, “The inner principles of corporeal things are concealed like bones within objects apprehended by the senses: no one who has not transcended attachment to sensible things can see them.”[iv] As to a description of the first stage, “natural contemplation,” I have not been able to find a detailed account of this experience. That is, so far I have not encountered a vivid “picture” description, so to speak, of what takes place and is seen. It also involves going beyond the realm of thoughts and discursive reasoning.[v] As St. Peter of Damascus says, a result of contemplation is the knowledge of, “the purpose for which each thing was created.”[vi]

The term “noetic vision of the archetypes” should not be taken to mean contemplation as a “miraculous experience” as noted in the previous letter. The heights of contemplation as delineated above are something beyond my capability to talk about and describe, since I have not apprehended them. The aim in using the term “noetic vision” is to emphasize that icon painting involves the use of the noetic faculty as the steering agent in the creative act. Through its spiritual knowledge, which is clear vision, it guides our reasoning, imagination, and manufacturing skill in an intuitive manner. There is direct knowledge of the archetypes and there is knowledge by transmission, both are a form of noetic vision as I will discuss shortly.

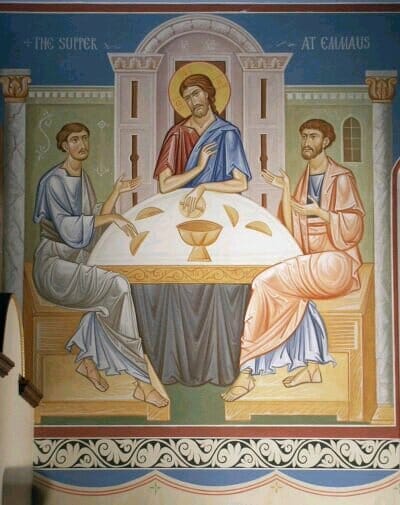

Nevertheless, in another sense, it can be said that contemplation is more accessible and that in fact we have experienced it. Not as the “miraculous” occurrence we tend to associate it with, but as the illumination of the mysteriological life of the Church, in partaking of the Logos in the Eucharist, “…He took bread, blessed and broke it, and gave it to them, then their eyes were opened…”[vii] Hereby we begin to see creation and the Scriptures as symbols, perceiving their inner meaning, in ways that those who have not taken the waters of Baptism fail to. We begin to see creation as a theophany, as a burning bush, radiating and enflamed by the divine presence, but not consumed. In the Transfiguration the eyes of the disciples were opened, and they were able to see the uncreated light of the Lords divinity, shining through His resplendent garments. So in the Church, to various degrees, we are able to see Him through the “garments” of creation and the Scriptures.

As St. Maximos says, “the mystery of the incarnation of the Logos is the key to all arcane symbolism…”[viii] The veil is removed in Christ as St. Paul tells us. In other words, we can say that there are degrees or stages of contemplation from glory to glory, according to our level of receptivity. In fact, St. Peter of Damaskos speaks of eight and describes what they entail. While, I might not have “experienced” that stage, which appears so lofty that it almost seems unreachable, the Lord every day guides us, instructs us, gives us inklings or intuitions and opens our understanding through the Spirit, as He did the disciples after the Resurrection. This illumination of the initiated faithful is so close to us that we take it for granted, as we take for granted that, “In Him we live and move and have our being.”[ix] Perhaps, we ignore these noetic visions because we are looking for great signs and wonders.

Be that as it may, we can also simply speak of contemplation as the activity of “being mindful” or “pondering things in the heart,” not according to their outward appearance, but according to the “bones”, so to speak, of the inner meaning or spiritual reality they manifest. This is I think why St. Dionysios calls the various interpretations of the mysteries in The Ecclesial Hierarchy a “contemplation” and why St. Germanus’ treatise interpreting the Divine Liturgy is called, Ecclesial History and Mystical Contemplation (theoria). Simply put, the “uplifting explanations,” as St. Dyonisios would say, of the symbols, are “contemplations.” I think this puts us in a better place to qualify the term “noetic vision” as something less removed and inaccessible. Talking about both the exalted and accessible nature of contemplation Metropolitan Kalistos Ware says, “It is common to regard contemplation as a rare and exalted gift, and so no doubt it is in its plenitude. Yet the seeds of a contemplative attitude exist in all of us. From this hour and moment I can start to walk through the world, conscious that it is God’s world, that He is near me in everything that I see and touch, in everyone whom I encounter. However spasmodically and incompletely I do this I have already set foot upon the contemplative path”[x]

Yet, in qualifying “noetic vision” as something less removed than what we usually expect, we should not oversimplify matters. When it comes to the creative act, the tension of proximity and distance as an integral part of this mystery should always be maintained and kept in mind. Therefore, in speaking of the “noetic vision of the archetypes” we mean both a “removed” experience of direct knowledge granted from above, and the more “accessible” apprehension of the inner meaning of the pictorial language of the icon as symbol. That is, as symbol uniting two levels of Reality, celestial and earthly, the material icon is a manifestation of noetic vision and as such transmitted knowledge. The “removed” mystical experience is described in the glossary of the English translation of the Philokalia as follows, “One of the goals of the spiritual life is indeed the attainment of spiritual knowledge which transcends both ordinary consciousness and the subconscious; and it is true that images, especially when the recipient is in an advanced spiritual state, may well be projections, on the plane of the imagination of celestial archetypes, and that in this case they can be used creatively, to form the images of sacred art in iconography. But more than not they will derive from the middle or lower sphere, and will have nothing spiritual about them. Hence they correspond to the world of fantasy and not to the world of the imagination in the proper sense.”[xi]

Prophetic Vision can be described as the imprinting of a celestial archetype unto the purified imaginative faculty of the prophet.

In other words, this description confirms that what we see in some icons is in fact a vision reified, a “re-presentation” of a model, or a “pattern” seen on the “mountain”[xii] of the imagination, in the middle realm, between the celestial and sensible spheres. On the one hand, here the celestial archetypes mentioned, could be understood as an image manifestations of logoi, in a level more intelligible than sensible. On the other hand, they can be seen as images in the sense the prophets apprehended them in their visions. As mentioned in the previous letter, not every iconographer will have this lofty experience. But once the celestial archetypes have been incorporated into the iconographic canon as prototypes, they are once again projected through the icon, and when internalized, being kept and “pondered within the heart,” they in turn become imprinted in our imagination. Guarded from fantasy by the canon, we can then become “mindful of” the imprinted celestial archetype in the process of iconography, and use it creatively in the painting of a new icon. As symbol the icon manifests the vision, and when we gaze at its anagogic depiction, we are uplifted to the apprehension of the celestial archetypes. Throughout the whole process, beginning at the initial projection of the image of celestial archetypes and ending in its third stage of re-presentation, noetic vision is involved, both in its “removed” and “accessible” sense.

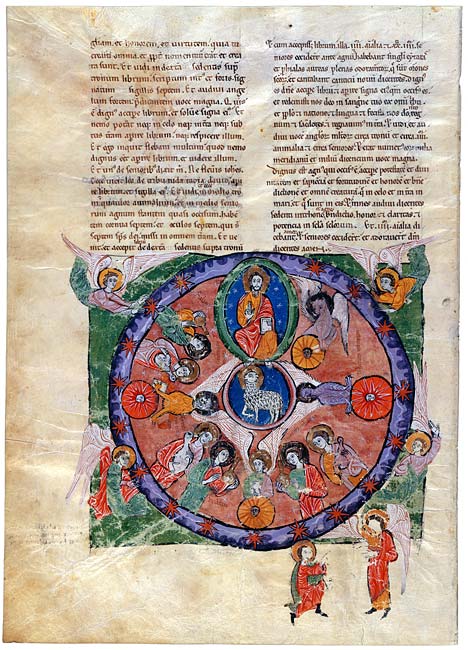

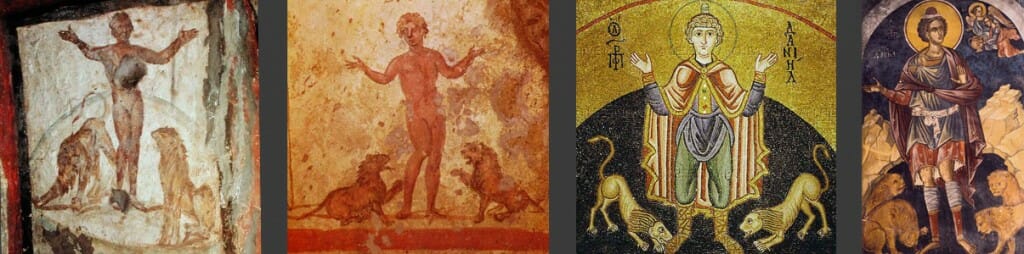

When it comes to the more accessible dimension of noetic vision, or transmitted knowledge, there arises a need to clarify the term “archetype.” In this context the term does not carry the connotation of logoi or the celestial realm, but simply means a pattern to follow in the execution of an icon. To clarify this lets briefly look at C. Cavarnos’ appendix of The Guide to Byzantine Iconography: Volume Two, titled, “Saint Nectarios of Aegina on Types in Iconography.”[xiii] St. Nectarios notes that, from the very beginnings in the life of the Church, certain events and personages, as those seen in the catacombs from the 2nd to the 4th century, became standardized into hieratic types, prescribed for the use of artists, and acceptable conveyers of a hidden spiritual teaching recommended to the faithful.[xiv] These types soon became canonical and predominantly unalterable, but also went through slight variations over the centuries.

As C. Cavarnos says, St. Nectarios, “…adds that the choice of subjects made from the accounts in the Bible for the formation of compositions and types for Christian art was automatically new. It was freely directed by the spirit and the system of symbolism of the Gospels and the writings of the Apostles.”[xv] After this passage Cavarnos introduces the term “archetype” by quoting Kontouglou who says, “The archetypes of Byzantine iconography are the result of centuries of spiritual life, Christian experience, genius and work. The iconographers who developed them regarded their work as awesome, like the dogmas of the Faith, and they worked, with humility and piety, on types that had been handed down to them by earlier iconographers, avoiding all inopportune and inappropriate changes. Through long elaboration, these various representations were freed from everything superfluous and inconstant, and attained the greatest and most perfect expression and power.”[xvi] In this passage the focus is not on the celestial archetypes as such, as described above, but on “a formation of archetypes from early types.” That is, a gradual canonical standardization of prototypes. The words archetype and “prototype” are then equivalents in this context, as a given pattern to follow, a kind of transmitted knowledge. As it will be shown below the “long elaboration” Kontouglou mentions, in which “everything superfluous and inconstant” is shed, involves what I would call the transfiguration of sense-perception.

St. Nektarios in discussing the origin and development of the canon is mainly concerned with the process of articulation based on the Scriptures, the Gospel and Apostles. In short, Tradition, the “spirit and the system of symbolism of the Gospels” directed the articulation. This of course, as pointed out by Kontouglou, involved centuries of spiritual life and arduous labor to arrive at “perfect expression.” Also, St. Nectarios, might be implying divine inspiration when he says that early Christian art was “automatically new,” rather than a matter of purely historical influences, but his focus is predominantly on the guidance of the Church through Tradition.

We see here more of an accessible approach to noetic vision, as the fruit of a creative process, involving the faithful’s collective effort, to arrive at the proper symbolic visual language that conforms to the spirit of living Tradition. This collective effort in turn reflects and communicates the apprehension of the inner meaning of the life of the Church, what St. Nektarios calls the esoteric or “hidden spiritual teaching,” which is then given visual form as reified vision. But in essence this “hidden spiritual teaching” contained in the symbolism of the Tradition is the ultimate celestial Archetype manifested therein, the incarnate Logos, the “mystery hidden before the ages.”[xvii] The apprehension of the inner meaning of life in the Church is a noetic vision which guides creative act, although not in the same sense of a sudden imprinting from above as described previously. As it will be shown, it rather involves a climbing, as by a ladder, from sense-perception (below) to things intelligible (above) through the imaginative faculty.

[i] See Glossary in The Philokalia Vol. Three, Faber and Faber, Inc., London and Boston, 1984,

pp.356-57.

[ii] As quoted in The Westminster Handbook to Origen, edited by John McGuckin, Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville and London, 2004, p.82.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] The Philokalia Vol. Three, Faber and Faber, Inc., London and Boston, 1984, p.58.

[v] St. Justin Popovich says, “ In the philosophy of the holy fathers, contemplation has an ontological, ethical, and gnoseological significance. It means prayerful concentration of the soul, through the action of grace, on the mysteries that surpass our understanding and are abundantly present not only in the Holy Trinity but in the person of man himself and in the whole of God’s creation. In contemplation, the person of the ascetic of faith lives above the senses, above the categories of time and space. He has a vivid awareness of the links that bind him to the higher world and is nourished by revelations that contain that which ‘eye has not seen nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of men.’(1 Cor.2: 9)” St. Justin Popovich, Orthodox Faith and Life in Christ, Translation, Preface, and Introduction by Asterios Gerostergios, et al., Institute for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, Belmont, Mass., 2005, p.153.

[vi] Ibid. p.275.

[vii] Luke 24:30-31.

[viii] The Philokalia Vol. Two, Faber and Faber, Inc., London and Boston, 1984, p.127.

[ix] Acts 17:28.

[x] Bishop Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Way, SVS Press, Crestwood, New York, p.120.

[xi] The Philokalia Vol. Three, Faber and Faber, Inc., London and Boston, 1984, pp.358-59.

[xii] Exod. 25:40; Heb. 8:5.

[xiii] C. Cavarnos, The Guide to Byzantine Icponography: Volume Two, HTM, Boston, Mass., 2001, pp.145-48.

[xiv] The types St. Nectarios mentions include: Adan and Eve; Noah in the Ark; The Sacrifice of Abraham; Moses Approaching the Burning Bush; Moses Striking the Rock with his Rod; Elias Rising to the Heavens; Tobias and the Fish; Christ; the Apostles Peter and Paul. Ibid. p.147.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Col. 1:26.

I was most impressed with this paper. Thank you for elaborating on a well articulated re-presentation of the writers of the Philokalia and upon an application of Theoria and Praxis with Icons.

Hello Tau,

I’m glad this re-presentation can be helpful. There will be another section coming on the same topic, so I hope you come back to read the rest.

[…] https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/archetype-and-symbol-ii-on-noetic-vision/Monday, Apr 22nd 8:00 amclick to expand… […]