Similar Posts

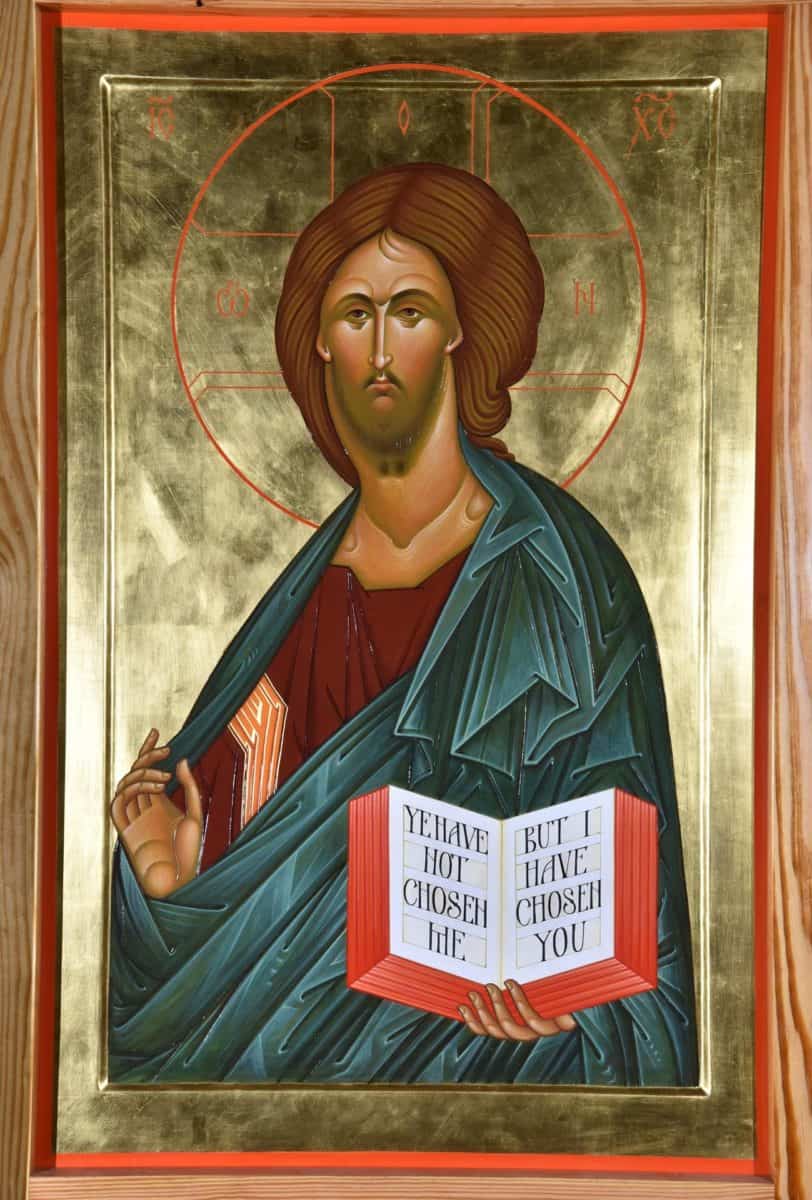

The iconostasis featured here is the culmination of an idea I have been developing for several years. It is installed at Saint Matthew the Apostle Orthodox Church in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. I would like to tell the story of how it came to be, and discuss the problems it is meant to solve.

The iconostasis is the single most important feature of an Orthodox church. It is the visual focus of the liturgy far more than individual icons, or chandeliers, or even the church building itself. It dominates the experience of the faithful, and it physically participates in the liturgy as the clergy and servers pass through it, opening doors and curtains. Despite its paramount importance, the iconostasis is sadly neglected in most American Orthodox churches. We do not have many beautiful iconostases, and we have more than a few that are frankly embarrassing. And nowhere is the situation worse than in mission churches.

Mission churches are, of course, left to fend for themselves. They try to collect a few icons, assemble a few amateur singers, and they do their best with what they have. But an iconostasis is not usually something that just turns up, like an icon or a singer. The mission has to build it, and since both expertise and funds for this are usually lacking, the result is often regrettable.

But if the mission has talented people who work hard to beautify the iconostasis, another problem emerges. The iconostasis becomes too good to be temporary, and the parish becomes attached to it. And when they are ready to build a real church building, the iconostasis becomes an architectural problem. It is typically scaled too small to suit a larger building, yet the parish still wants to keep it, so they try to enlarge it, and their architect struggles to design the building around it. This is never ideal. I know from my own experience designing churches how intractable this problem can be.

It does not need to be this way. There is no reason that every mission should re-invent the wheel and try to create its own iconostasis from scratch. And there is no reason that portable mission-iconostases need to be repurposed as permanent-church-iconostases. There is a better way.

I propose that semi-portable iconostases, designed to be set up in rented spaces, should be their own typology. They should be designed to the proper scale for that type of space. But they should be professionally designed and built, as the purpose of a mission is to present Orthodoxy in the fullness of its beauty. Ideally these mission-church iconostases would be owned by the diocese and loaned out to missions as needed. When a mission is ready to build a church, the iconostasis should go to another mission. A new church building deserves its own professionally-designed iconostasis, customized to the space, and at a much larger scale.

Fr. Joshua Trant, of Saint Matthew Orthodox Church in Baton Rouge (OCA), contacted me in 2018. A generous donor had offered to pay for an iconostasis. But since they occupied a rented space, and were likely to move to another rented space in the future, the iconostasis could not be permanently installed. I told Fr. Joshua of my idea for how to handle a mission church iconostasis, and he agreed to this approach. I would provide his church with a fully-professionally-made free-standing iconostasis, and if they ever build a permanent church that requires a larger one, then they will pass it on to another mission.

In designing the iconostasis, I built upon what I had learned from a prototype mission iconostasis we had done in 2016. That project had been done on a shoestring budget, and had many shortcomings, but it presented an aesthetic direction that seemed to hit the right note. It was simple and elegant, depending more on the natural beauty of wood than on ornamentation. It looked distinctly in the tradition of American woodwork, almost as if Shaker craftsmen had built an Orthodox iconostasis.

With a proper budget to work with, I set about designing an improved version of this idea, with thicker material, better joinery, and recessed doorposts for more depth. It would be built like traditional architectural paneling and assembled on site from three large segments.

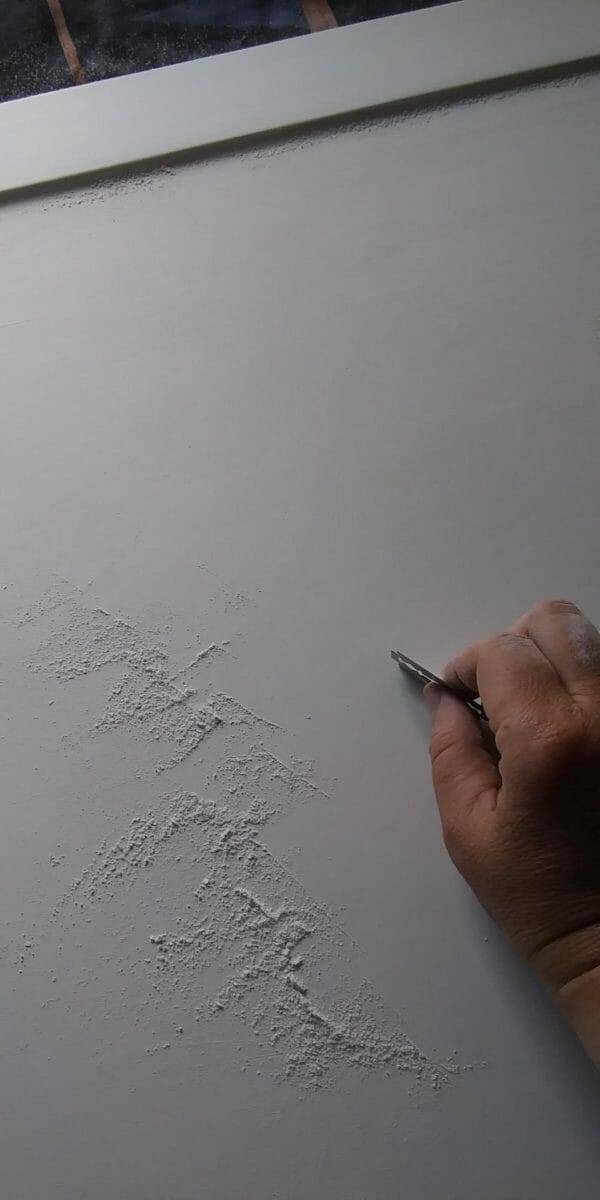

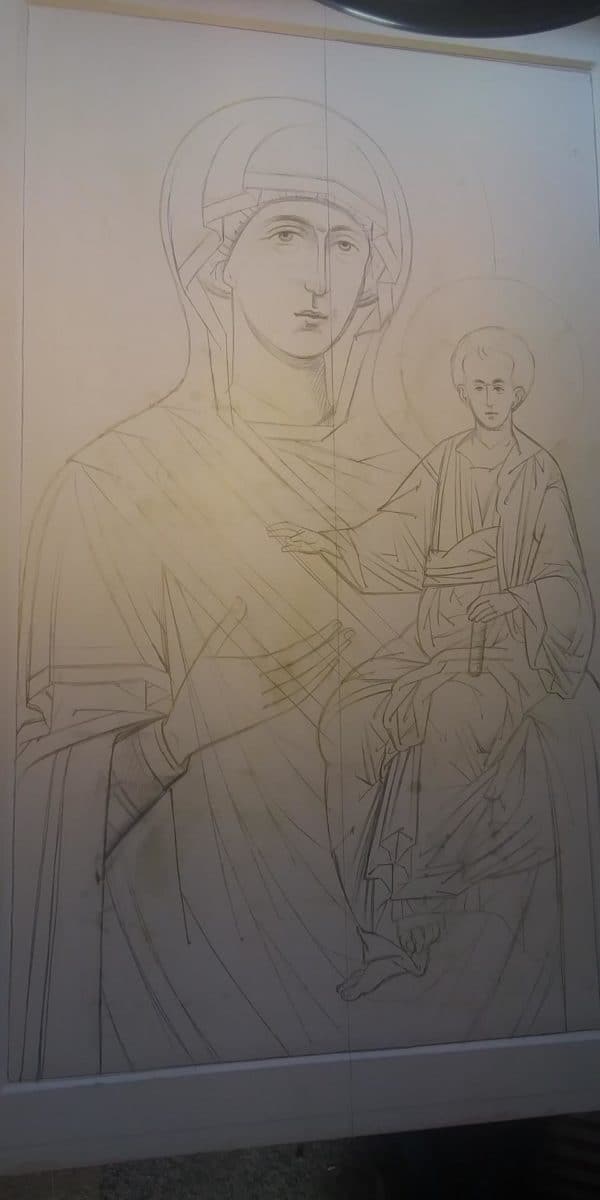

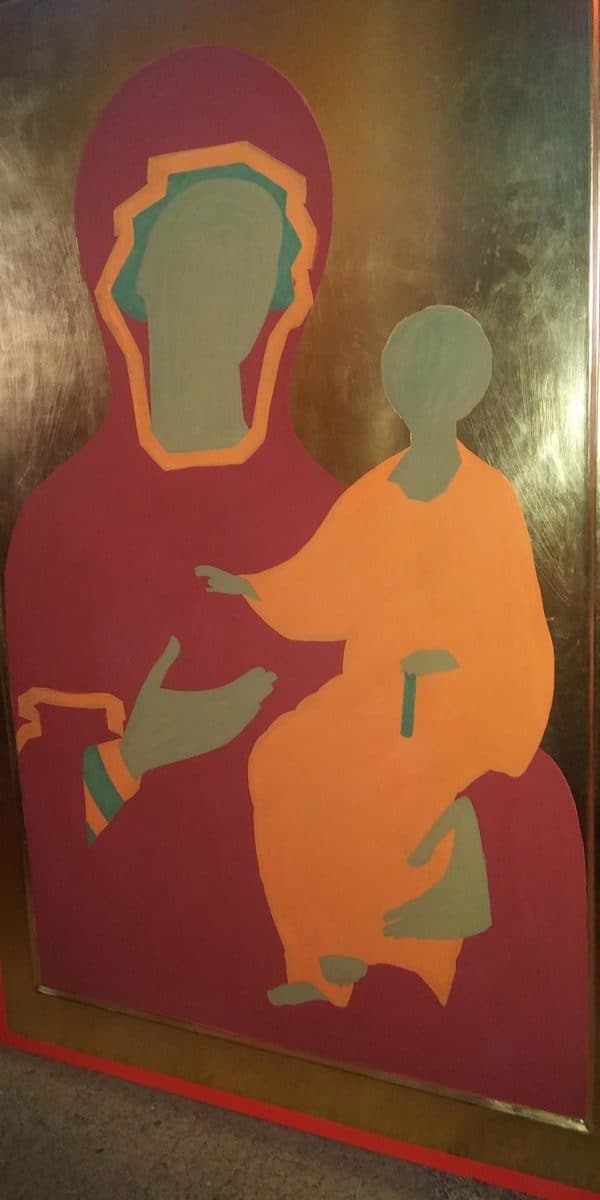

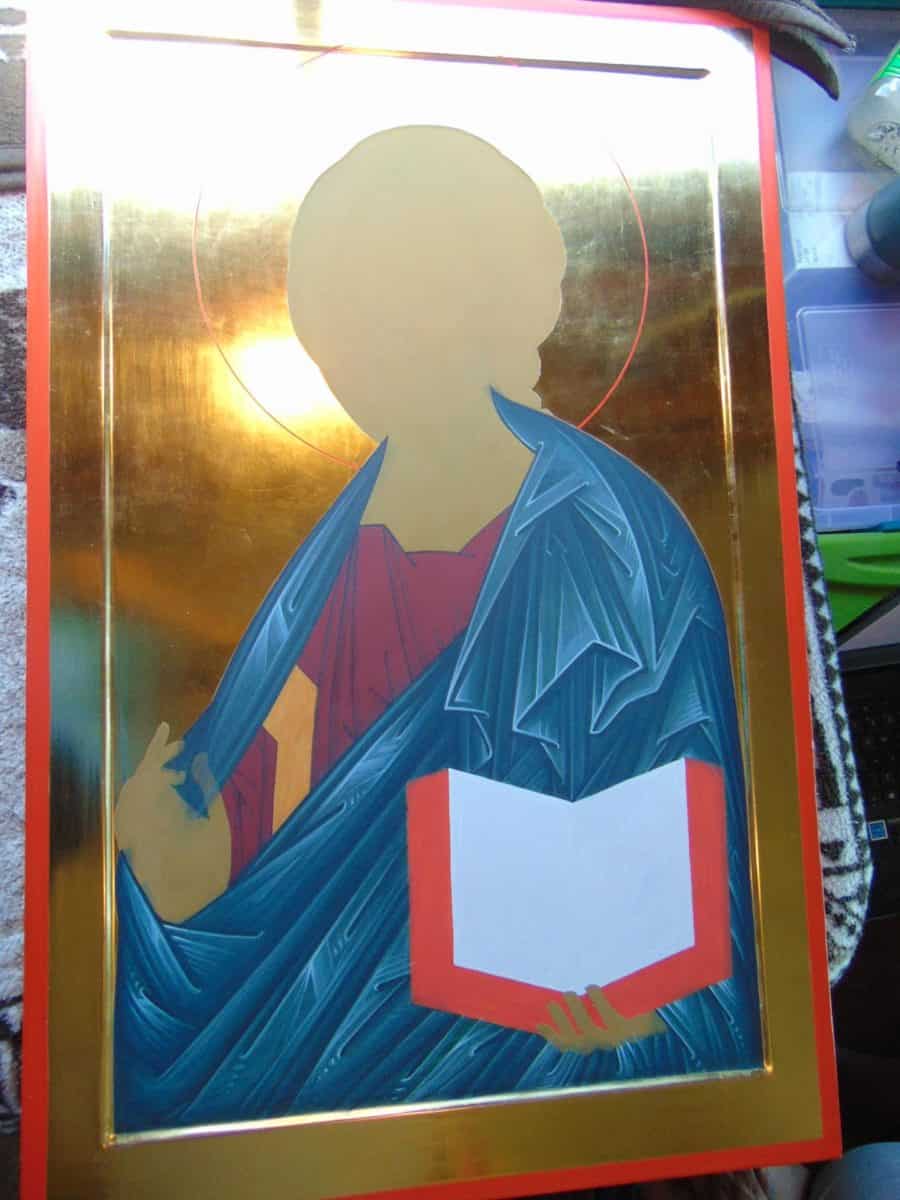

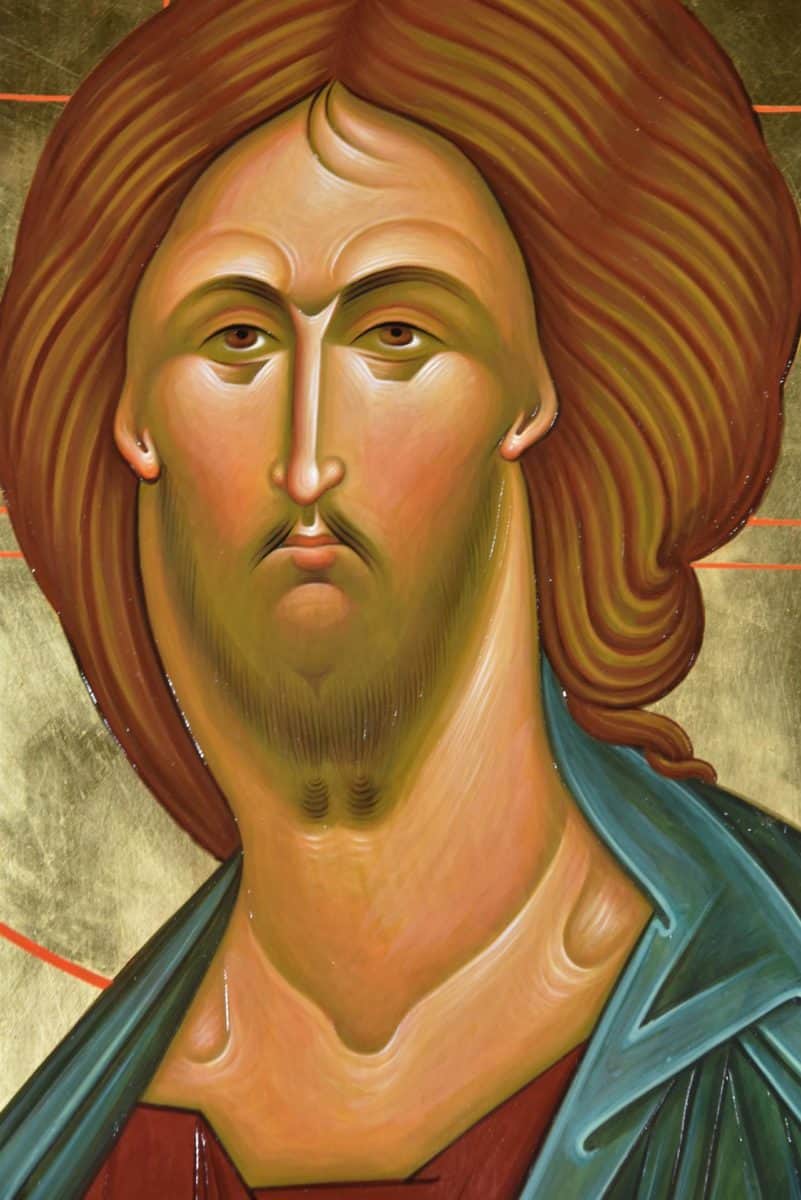

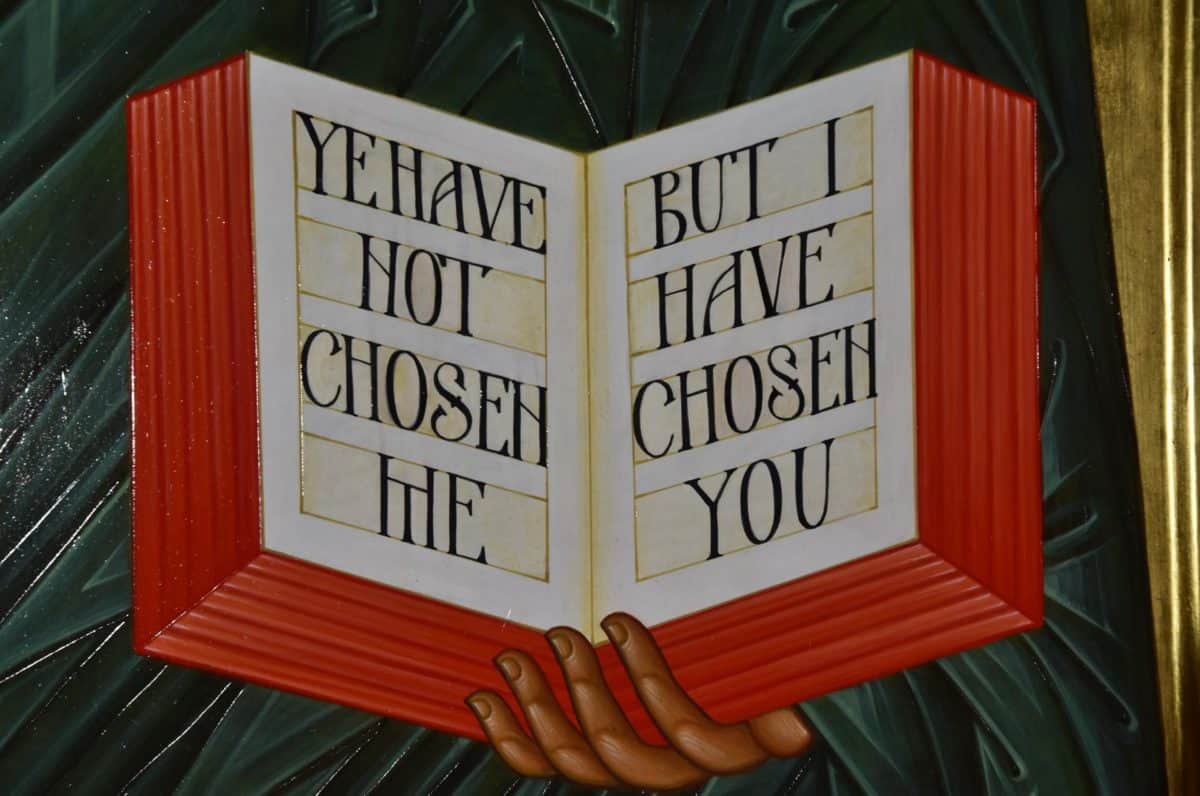

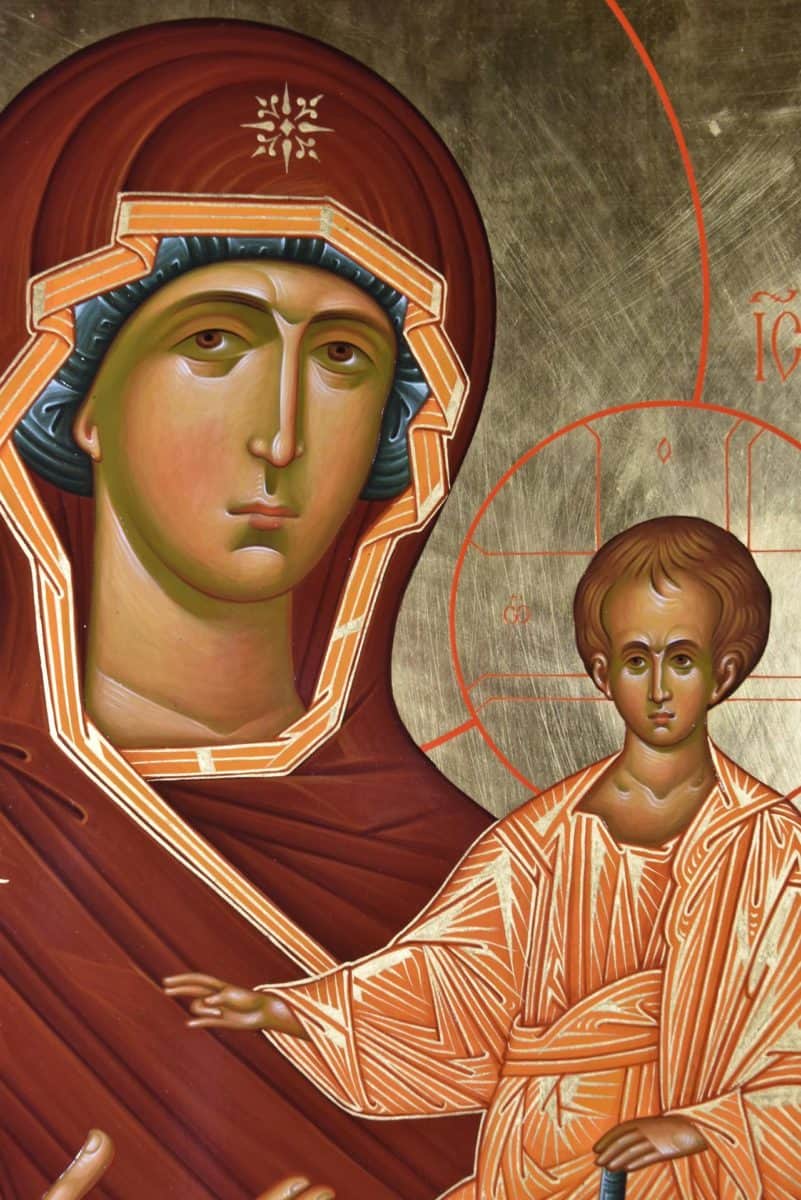

I hired Saint John’s Workshop in Wisconsin to make the icon boards and doors. They are CNC-routed from 1” thick Baltic birch plywood. These were shipped to iconographer Natalia Aglitskaya in South Dakota, who gessoed, water-gilded, and beautifully painted them. Meanwhile, here in Charleston, South Carolina, I hired Timber Artisans, a professional furniture-making and timber-framing shop, to build the iconostasis framework. It is 16 feet wide and 8.5 feet tall.

We built the framework from Southern Yellow Pine, an inexpensive locally-grown wood. Yellow pine is not often used for fine woodwork such as this, because of knotholes, resinous patches, and high contraction. But with careful selection of good material, it can be done. I am very fond of yellow pine, because it has a rich golden color and prominent grain. If this iconostasis were built from a flawless and uniform wood, it might look too plain. The surfaces would demand some ornament so that their plainness would not detract from the richness of the icons. But the yellow pine, with its knots and intense grain, is almost ornamental in itself. And its golden color perfectly complements the gilded icons.

After the woodwork was complete, I oiled and varnished it using a mixture of tung-oil and urethane resin. I installed the icons and doors using wrought-iron hardware, and had it shipped to Louisiana wrapped in blankets by an art and antiques shipping service.

It is now installed in the mission’s commercial rented space, and serves its intended role in the liturgy. Fr. Joshua reports the following:

The reaction from people has been dramatic. The servers take their responsibilities more seriously. The faithful are awed by the icons. Mission life can be difficult – we talk about the beauty of our worship but often the most basic elements (icons, iconostasis, lampadas, etc.) are not beautiful. Most of my parishioners are converts and have not had much exposure to other Orthodox churches. So for many of them, the iconostasis and icons are the first “real” ones they have seen not in pictures. I have noticed we treat the space more like a church – we are quieter, we move less, we talk less, we anticipate more.

I hope that this project will be the first of many more. And certainly they do not all need to be the same. There are many variants on this design that I’d like to try. I would particularly enjoy doing one with non-gilded icons and a framework that’s painted with a decorative color scheme, rather than varnished.

To offer an idea of costs, if I were to furnish another iconostasis similar to this one, the total project cost would be about $30,000. It can be done in phases, with structure first and icons coming later. And I can provide architectural drawings for the structure if a parish has the skills to build it themselves.

![]() Andrew Gould’s work can be seen at New World Byzantine

Andrew Gould’s work can be seen at New World Byzantine

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

Wonderful work. I am particularly impressed by the mission priest’s observation about how the genuineness of the iconostasis has not only changed the space, but also the movement therein. In regards to your proposal for a 2.0 version, are you familiar with the work of Elena Tsitoglou? I believe she paint icons in Cyprus. Her style reminds me much of this painted approach: https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=1101687970026052&set=pcb.1101687993359383

That’s a great example. Beautifully done. And there’s plenty of precedent for painting like that in American folk art – Pennsylvania Dutch chests, for instance.

Exactly. I’m amazed at some of the early Americana needlework that Presvytera Krista West displays with her company Avlea that are so reminiscent of Greek and Baltic works. Often times a slight tweak to the color palette is all that is required to shift an entire continent.

Congratulations! Well done! Well done, indeed!

Beautiful, Beautiful Work. A wonderful idea of passing this down to another mission church if the parish moves to a larger location.

I think there is more to unpack from your comment that, “The iconostasis is the single most important feature of an Orthodox church.” Not that I disagree, exactly, but I think it points to several questions. First, why is the iconostasis seen as “most important” than, say, the altar? Second, given the American religious landscape – a reductionism common to the West to ID a hierarchy of what is “most important” together with the Roman Catholic focus on the mass and the Protestant focus on atonement (both pointing clearly to the altar as a focal point) – perhaps it isn’t surprising that American Orthodoxy has tended to focus on a certain understanding of what is “essential”. Later, when financially able, American Orthodox churches seem to either go deeper in that direction to create the most theologically correct (and therefore “most important”) iconostasis or they go as far as possible in the other direction recreating the most grand of Old World iconostases (in a way pointing to a change in what might be seen as truly “most important”).

This is a very interesting topic. Of course I am speaking of visual importance. If one is speaking of sacredness, then the altar is most important, or maybe the chalice, or far more so, the contents of the chalice. But at each step of increasing sacredness we see decreasing visual prominence. The most sacred things are veiled and invisible. That’s no accident. Sacred and secret go hand in hand. From an architectural standpoint, this is a conundrum. How do we give visual prominence to something small and hidden? It does not make sense to lavish the greatest artistic effort on the altar when the altar is mostly blocked from view and usually veiled by cloths, and not very large to begin with.

So the church has always found ways to surround the altar with visual glory on a bigger scale. In the western church this takes the form of a reredos – that splendid wall of sculpture and color that rises up behind the altar, visually dominating the entire church. The reredos itself is not sacred, but its artistry is obviously there to honor the altar and the sacrifice that takes place there. I think that in Orthodoxy the iconostasis serves very much this same role. When you enter an Orthodox church, you instantly know which end is sacred – which direction you’re supposed to face. The iconostasis shows you the liturgical order of the space. And by facing the iconostasis, you face the altar. The iconostasis literally reveals the sacredness of altar by showing the saints and angels gathered around it. It actually makes the altar sacred by simultaneously veiling it from view, while also making visible the heavenly host around it. That which was visible is veiled, and that which was invisible is revealed. This is as close to a miracle as art can get. In my opinion the iconostasis is the single greatest invention in the history of liturgical art – the perfect expression of the very concept of sacredness.

What a beautiful iconostasis! This mission church is richly blessed.

Dear Andrew, thank you for sharing your work! I love the bare wooden texture and how actively the pine-tree works in this very intense ensemble. It gives the feeling of authenticity and materiality to the iconostasis structure.

My only hunch is, that for this conceptual low-budget project the backgrounds on icons could also demonstrate less expensiveness and correlate more with the timber.

Not sure, what reason pushed together the natural rich expression of pine-tree and monetized richness of fully gilded backgrounds?

History of iconography has great examples of deepest spiritual treasures, – icons with colored backgrounds with no gold on them. Even though iconography always operates traditional symbolic language, it looks very disturbing when someone crushes together the modernity of minimalistic wood and presumably traditional gold without traditional sensibility in it’s use.

Sorry for being tough. I really love the idea of portable iconostasis as a universal structure, – an Orthodox Altar Screen for any church building!

Thank you again for sharing.

May God help you in your projects!

Hello Philip. I partly agree with you. Certainly people in historical times would not have paired such rich icons with a plain wood framework. This is why I’m interested in doing an iconostasis in more of a village/folk style, with simple un-gilded icons and painted wood, of which there are plenty of historic examples.

On the other hand, Americans are very fond of beautiful unpainted wood. It has been a ‘signature’ of American craftsmanship for centuries. And to my modern eye, the gilded backgrounds do complement the polished pine quite effectively. So perhaps there is room here for a new juxtaposition – something not exactly seen in times past.

I will keep experimenting. I would enjoy trying this with simpler icons and various colored backgrounds, maybe even looking to colonial-American portraiture for inspiration.

The timber is stunning and reminiscent of older baltic pine furniture and woodwork which one finds in Australia (and similarly in Scandanavia). Coming from NZ originally, a lot of the colonial churches built of wood also have this warm beauty when left unpainted.

I would endorse seeing how less richly gilded icons work, esp their lovely muted tones.