Similar Posts

One of the points many OAJ contributors have been trying to bring across is that the medium out of which sacred art is made and the artful human act of fabrication are important on a symbolic and theological level. This question of materiality and production have become crucial ones in our age of mechanical reproduction in which automatic industrial processes imitate noble materials and forego the human act of creation.

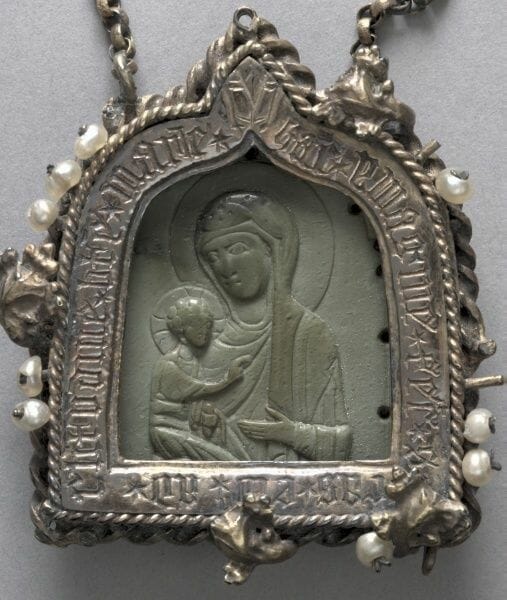

As I myself attempt to renew the ancient art of steatite icons, I thought it would be appropriate to look at how the Byzantines saw the question of materiality by focusing on this particular medium. Loli Kalavrezou, a Harvard expert on Byzantine Art has done much work concerning the question of steatite icons and their meaning in the ancient Orthodox Church. One of her approaches is to look at Byzantine poetry to gain a vision of how the particularities of steatite as a medium for icons were interpreted.

The Byzantines named what we now call steatite “amiantos” or rather “amiantos lithos” which means immaculate or unspotted stone. Already one can gather the meaning attributed to it. Steatite comes in many colors, green or gray with variations, veins and grains in it. The Byzantines though preferred the greenish stone, attempting to find pieces that were immaculate. Here is part of a late Byzantine poem, a kind of ode to a particular steatite icon representing the Nativity of Christ.

I honor you, o stone, although you are small to look at, nevertheless you contain within you the uncontainable.

But you are truly unspotted (amiantos),

because you represent the unspotted (amiantos) mother.(1)

There is a very powerful relationship made by the poet to the Theotokos in the poem, first the stone is called “small yet containing the uncontainable”. This refers to the stone’s capacity to hold the image of Christ by using a language which is usually attributed to the Virgin Mary’s womb being small, but mysteriously becoming larger than the heavens in having contained God. The relationship to the Virgin Mary is also compounded because the same word, amiantos, is used to qualify the stone and then the Virgin. This is not a singular event, Kalavrezou cites many examples. There are also other characteristics of the Virgin and the stone which are put into an analogical relationship. And so addressing a steatite Icon of the Theotokos, another poet exclaims:

You unburnt burning bush

you have been carved perfect into the pure (amiantos) stone

Before fire iron does not endure as (this) stone does. (2)

Here the particular characteristic of the stone, that is its capacity to resist fire, is placed in relation to the burning bush, which is itself an image of the perpetual virginity of the Mother of God, having manifested the Divine without being herself consumed.

One of the objections we have seen arise to our insistence on the importance of the human hand in the production of sacred arts is that in iconography the ancient Church was only concerned with the image itself and its relation to the prototype, not to the means of production. Although it is true that the 7th ecumenical council was focused on this question, this does not mean that ancient Christians were not concerned with the symbolism of human artfulness. We can therefore read in another poem addressed to the same icon of the Nativity with a bust of Christ mentioned earlier:

Blessings upon you, sculptor’s hand,

on the stone from the mountain uncut by (human) hands

him you delineate on unspotted (amiantos) stone

who came forth from the unspotted (amiantos) Virgin.(3)

In just these few lines, the poet does much. He starts by connecting the artists cutting of the image of Christ into the stone to the dream of Nebuchanezzar interpreted by the Prophet Daniel (Daniel 2). In this dream a stone uncut by hands comes out of a mountain to crush the large statue representing the four Kingdoms. This vision has traditionally represented the Virgin (The mountain uncut by human hands yet “producing” a stone, that is giving birth while being a Virgin) who gave birth to Christ (a stone uncut by hands, that is without a human origin). And so all of this is put together by the poet: The artist is blessed because he cuts out an image of Christ on a material which is “amiantos” just as Christ himself came as the uncut stone from the “amiantos” Virgin. And so the act of the artist is made analogous to the incarnation itself through his forming an image of the Logos from “Primal Mater”.

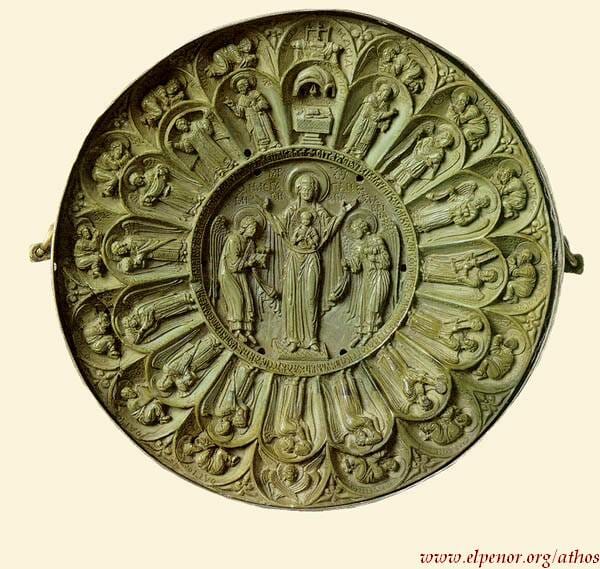

Just to show how integral and complex this can become, I will cite a final example mentioned by Kalavrezou, that is a steatite paten from the monastery of Panteleimon in Athos which represents the Theotokos with child surrounded by a series of prophets. Part of the poetic inscription on the outer edge of the paten reads:

The meadow and the plants and the light with three rays.

The stone is a meadow and the row of prophets are the plants.

The three beams are Christ, the bread and the Virgin.

The maiden lends flesh to the word of God,

and Christ by means of bread distributes salvation. (4)

Here it is the green color of the stone which is reffered to when the poet writes: “The stone is a meadow and the prophet are the plants.” Through its color, the stone takes on the “feminine” symbolism of matter once again, the notion of the “space” out of which comes life, and so the prophets and their scrolls holding inscriptions of their sayings appear like fruits or leaves springing out not only of the stone, but of the Virgin and Christ at the centre of the image. The feminine symbolism of matter is also present in the fact that the object is a paten, a receptacle for the holy bread that is Christ. But in terms of material symbolism, the artist has taken this even further because on the scrolls of the prophets, several of the texts chosen refer to the stone as a material, so for example “Inscribed in the scroll of Daniel is the verse “you saw a stone cut out of the mountain without hands” (Dan. 2,45), while Habakkuk’s scroll reads “the holy one from the shady mount Pharan” (Habakkuk 3, 3). (5)”

We can see through these very few examples how beautifully the Byzantines related material symbolism with the actual content of the image, and we can also get some insight into the role of the the artist, seen as posing a sacred gesture in creating this image. What is also very powerful in the particular case of steatite icons, is how steatite, through its analogy to the Holy Mother, becomes an image of Materiality itself. It becomes a symbol for the transformed matter, the support, the opening to the Divine which is the very womb of the Mother of God.

———————————————————–

1. Verses on a Steatite which has the Birth of Christ carved on it and above the Bust of Christ. By the Hagionargyrites, translated by Loli Kalavrezou-Maxeiner in Byzantine Icons in Steatite, Vienna, 1985. p.82 I added the transliteration of amiantos to point to the connection.

2. Ibid p.81

3. Ibid p.82

4. Ibid p.83

5 Ipid p.84

Thanks for sharing these poetic insights into the minds of our predecessors. When you gave me some pieces of steatite with which to experiment, I found the material qualities of the stone quite remarkable and surprising. It is soft enough to easily scratch and carve with a knife, and yet so tough that it is quite difficult to chip or break even with heavy blows from a hammer. And it can be heated red-hot with a blow torch with no risk of cracking. These are very unusual qualities for stone, so it is not surprising to me that ancient craftsmen would consider it perhaps a little magical.

The green-gray color is also quite interesting. It is a cool and calming color, relaxing to look at. And yet it is not cold and lifeless – rather figures and organic shapes carved into it seem soft and alive.

One difference between the ancient perception of the stone and how we see it with modern eyes is the matter of imperfections. In ancient times, very few materials were perfectly uniform. Even glass and ceramics were full of bubbles and flaws. So a flawless stone was remarkable. But nowadays, almost everything manufactured has a plastic uniformity. When I have shown people one of your carvings made from a perfect piece of stone, they assume it is a plaster or resin casting, but when they see a piece that has veins and spots, they are much more attracted to it. So our modern context has reversed our perception so that we now see ‘defects’ as ‘organic character’. I don’t think this is a bad thing – one could just as easily write a poem suggesting that the lively veins and colors in a carved icon symbolically connect it to its prototype.

I was wondering if you would pick up on this, I almost included that story you mention in the article to point out exactly what you are saying. Kalavrezou mentions other poems about precious stones in which the stone is praised for its colorful veins and so you are right that we could see it in that manner, especially since the Kenyan stone I have is full of more vivid veins and colors than the stone the Greeks had access to. It is a funny thing though, I often think of the modern world as a “muddy mixture”, but there is also this excessive perfection of homogeneous reproduction which is also “dead” in a different way. In the Bible, there are some interesting places where people have an “excess of purity” and this is something I am hoping to write about at some point. But just as a hint, we see it in the story where Miriam and Aaron criticize Moses for having a foreign (and dark) wife. Their punishment is that their skin becomes white as snow, and so here the “whiteness” is a punishment, almost like a natural consequence of their excess of purity in regards to Moses.