Similar Posts

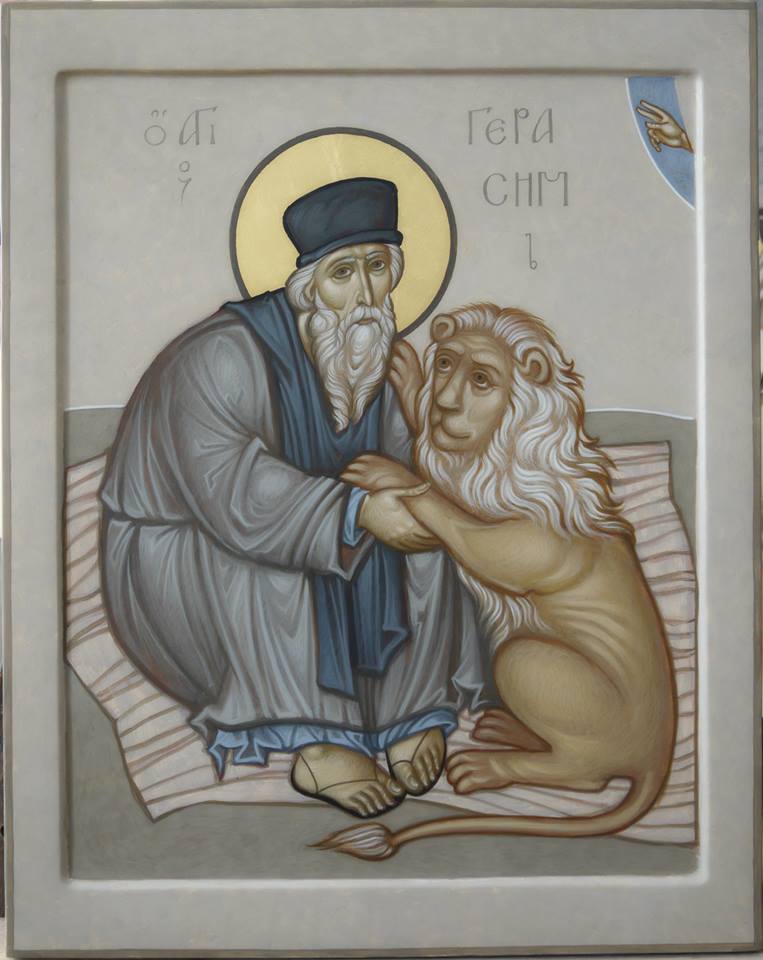

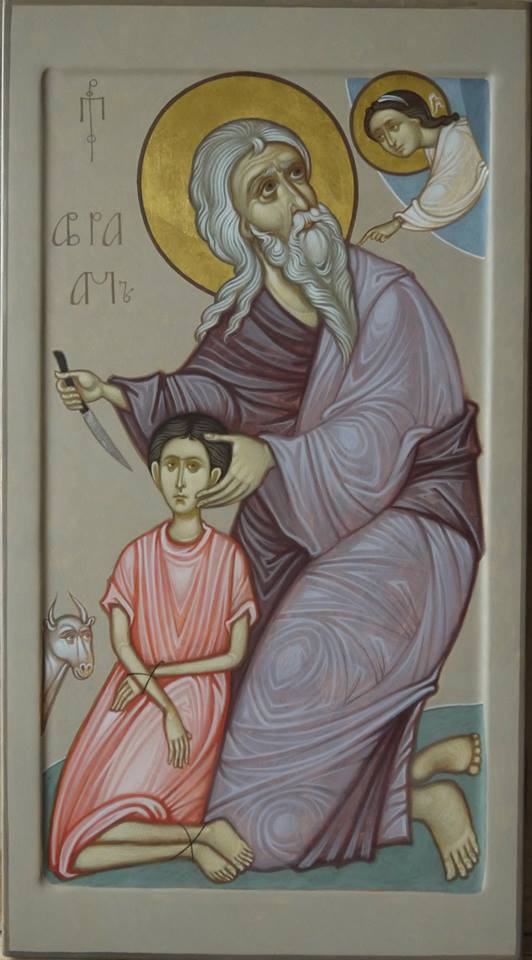

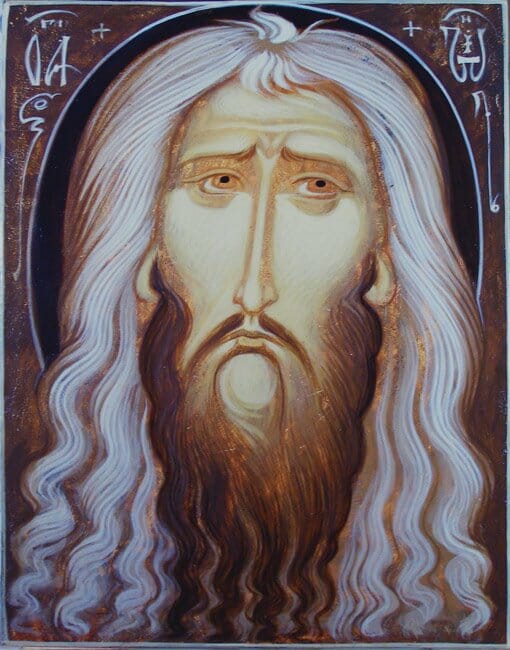

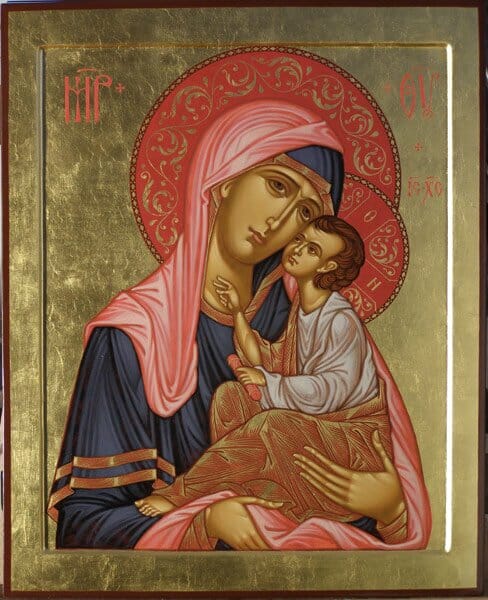

The distinctively fresh and masterful work of Maxim Sheshukov, a contemporary iconographer working in Sviyazhsk (Kazan region of Russia), is another example of the best synthesis of creative interpretation and conformity to Tradition which we can find nowadays. His work was mentioned in passing in a previous article on Contemporary Iconographers of Russia, but I thought it would be important to highlight his work as exemplary of the diversity and flexibility possible within our ever-renewing and living Tradition.

The more we look around, it becomes clear that the revival of icon painting has entered into a second stage. If the first could be described as the needful copyist stage, a studying “from without” to learn the grammar, after a long period of estrangement from the Tradition, today we find more iconographers producing works “from within,” daringly “thinking outside the box,” with their own poetic sentences to articulate. The internalization of the Tradition has become more evident in recent times. Copying has given way to authentic expression.

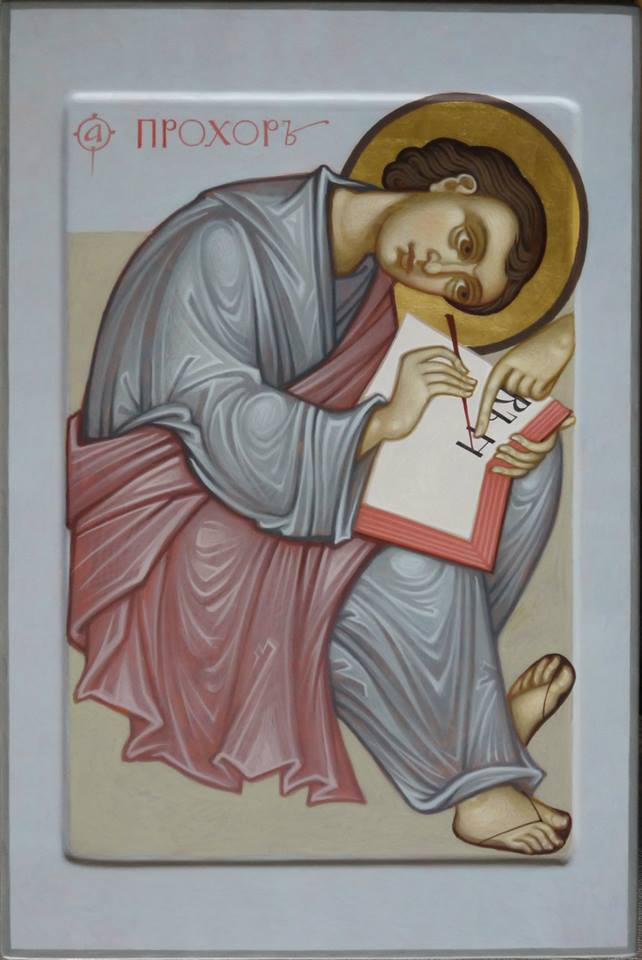

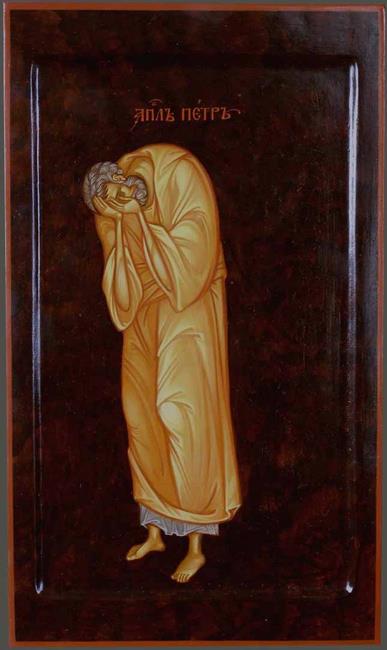

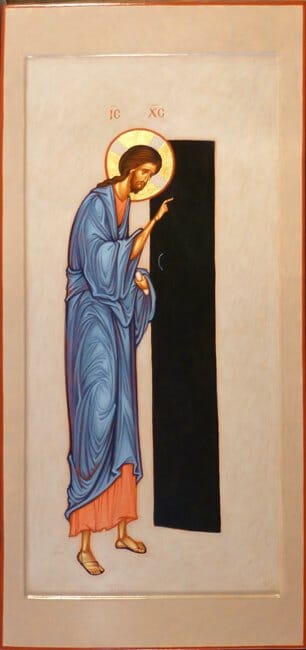

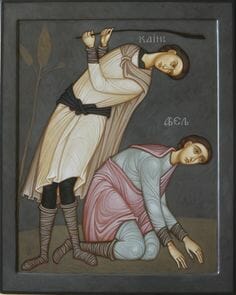

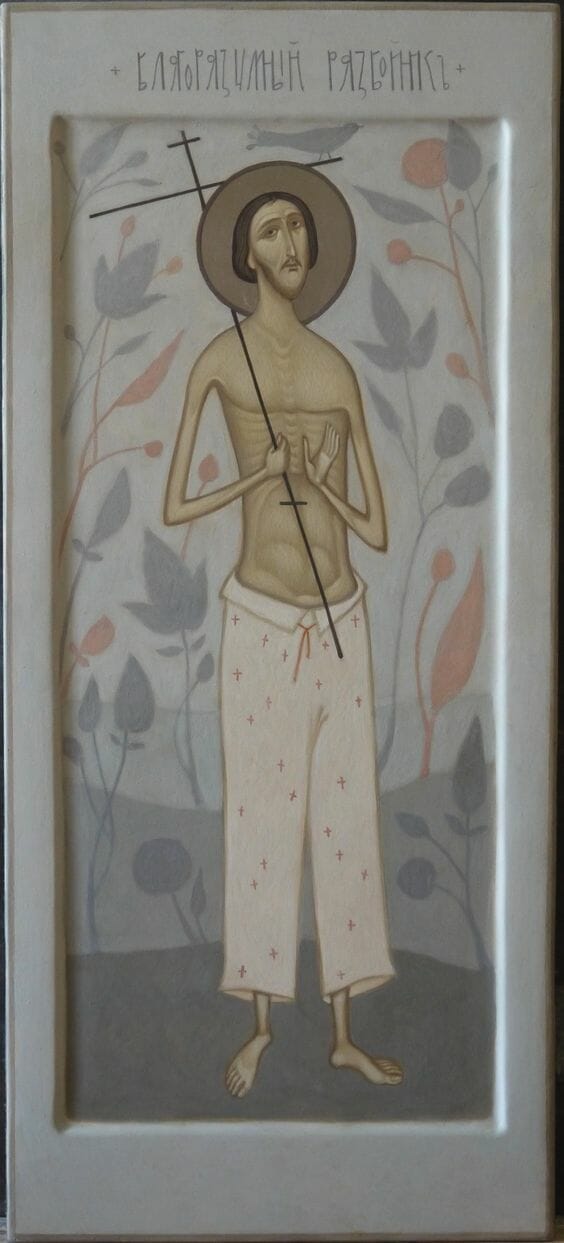

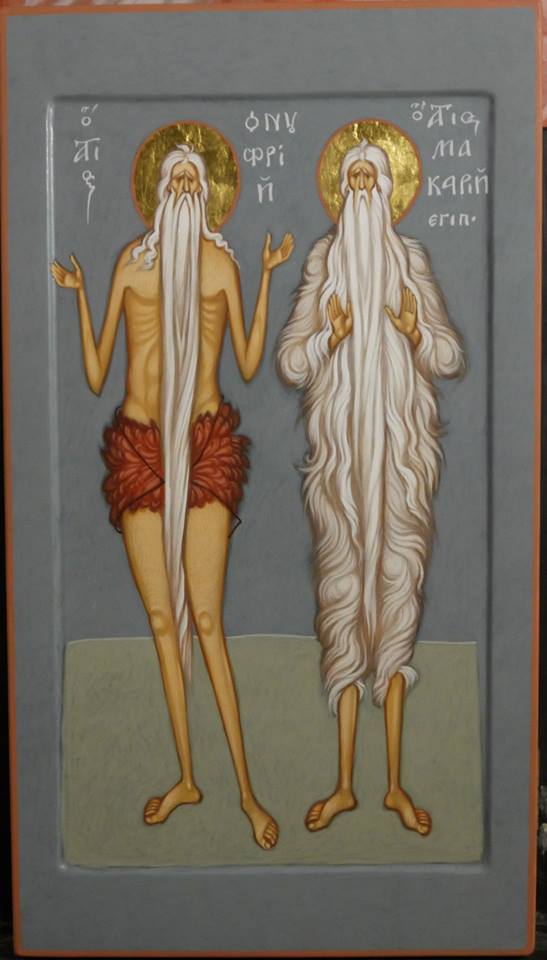

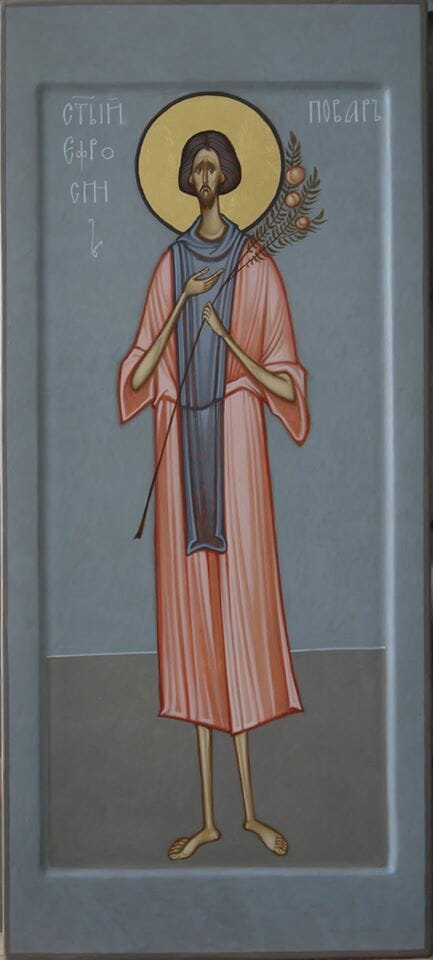

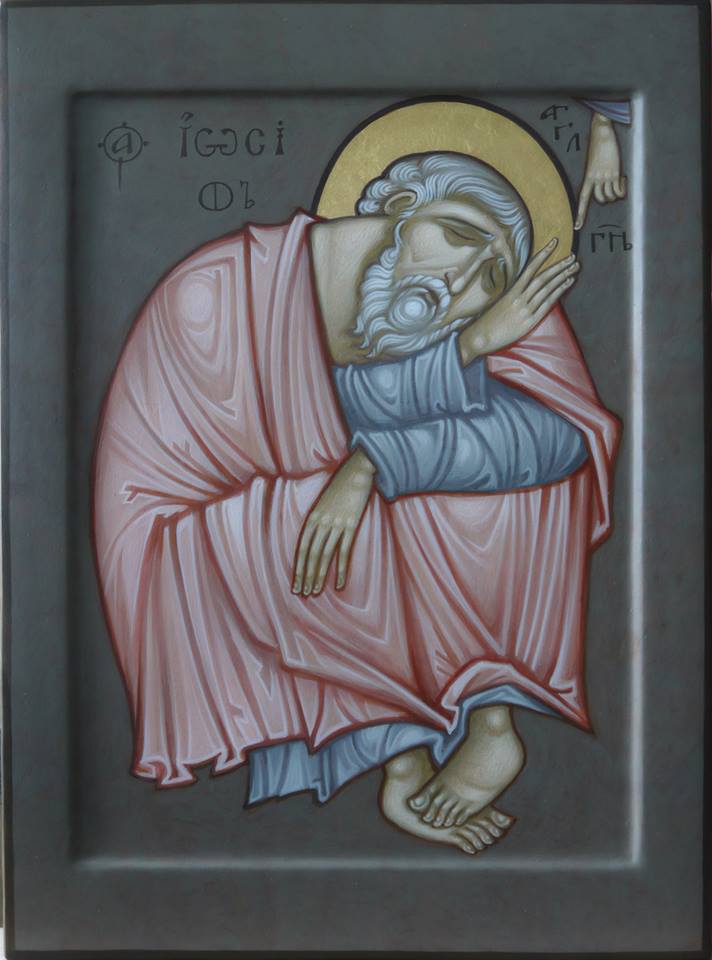

Thus in Maxim Sheshukov’s poetic work we encounter unquestionable dexterity, compositional flexibility, gracefulness of line and subtlety of color. There is also a kind of minimalism in his treatment of the backgrounds. However, the simplicity of the background pictorially works more as an energized field, rather than mere absence. It is as if the void manifests the divine Presence. Overall there is an all-embracing sense of joy in his delicate use of pastels, warm and cool grays. At times we encounter a child-like whimsicality. It is as if we are seeing through the profound purity of a child’s inner eye. Even if the scene depicted is Judas Accepting the 30 Pieces of Silver; hope, mercy and serenity are not too far distant. Not only are the usual prototypes readily discerned, but also he depicts moments rarely treated in isolation, such as the Slaying of Abel, Judas Accepting the 30 Pieces of Silver just mentioned, Zacchaeus Climbing the Sycamore Tree, Peter Weeping for His Denial and Christ Knocking at the Door.

The elongation of the figures and exaggeration of facial features could be taken by some as unnecessary cartoonish stylizations, but these are some of the elements in the work that communicate that sense of other-worldliness which is to be expected of an icon. Let us not forget, in a “cartoon,” or rather a “caricature,” we have the essential elements of the person depicted, their unique characteristics. Hence “caricature” is a form of abstracting or “drawing out” of those elements that best communicate the unseen truth of the subject. In short, the invisibly is made visible through abstraction. This is most often done to ridicule, as satire, yet it can also be done as a way of praise, that is, of glorifying a saint. This is exactly what we find in most abstract works of the Tradition and this is what Maxim Sheshukov’s work thrives on. Hence in the samples that will follow what can be seen as the influence of Modern art is in fact nothing other than what has been with us all along in the Tradition, for “there is nothing new under the sun.”

Thank you so much for this. It is the most clear commentary I have heard on this topic.

Thank you for sharing your insights and for bringing this work forward. I have always admired his work. His creativity is astounding. There are pieces here I have never seen before. I am greatly inspired as an artist striving for creativity within the tradition but even more so moved and inspired in my faith as an Orthodox Christian. The images reveal great ethos and I am renewed by seeing them. Thank you for your great and fervent work.

These icons are staggeringly beautiful, almost so much so that I feel I must look away before I am overwhelmed with emotion. I am especially interested in the choice of dark subjects for some of these – Judas, Cain, Peter’s despair. If we take a narrow view of icons as representing saints and heaven only, we might say that these subjects cannot be painted in an icon. One would never pray to Judas. But these images, the way Sheshukov paints them, are immensely edifying. They are full of sympathy and pain. We see ourselves in those villains, and turn away crying, like Peter himself. They inspire tears of repentance, and there can be no higher calling for liturgical art than this.

This work is a perfect example of how icons are ultimately meant to be Scripture in pictorial form. It shows how word and image are two sides of the one coin of embodied Tradition; complementary ways of manifesting life in Christ. Scripture exposes the totality and complexities of fallen human nature, but all is permeated with the presence of God, meant to edify, to remind us of our true calling and lead to repentance. Sensationalism falls to the wayside and we are brought to the contemplation of virtue. This should be the principle determining the choice of subjects and the way we depict them in icons. There is no doubt that these icons follow this standard. I agree, ” there can be no higher calling for liturgical art than this.”

Andrew, I had the same reaction. I had to look away from the Judas and Cain icons, as they nearly brought me to tears. Thank you Fr. Silouan for sharing Mr. Sheshukov’s work. I have often struggled with the idea of where expression fits within tradition, and I agree, this is an excellent example.