Similar Posts

Holy icons act as signs that point to the immediacy of the depicted. The icons present to the beholder a way of being in relation with the signified. It is precisely this intimacy which many find troubling. The on-off Iconoclastic Controversy in New Rome on the Bosporus that spanned nearly a century (AD 726–87 and 815–43) centered on the suspicion that the beholder merges the reality of the represented with its representation to the extent of worshiping its material substance. The charge was (and is) that sign and signified become so intellectually and emotionally fused for the beholder that he regards the image as the embodiment of what it depicts. That is, the depicted inheres, rather than just appears in the image.

Much has been made of the influence of Koranic dogma on the iconoclasts. By 651 Islamic invasions had subjugated the Christian territories of Syria, Mesopotamia and Egypt. Damascus as a major center of Orthodox theology fell to the Muslims nearly a full century before Emperor Leo III issued a series of decrees from 726-729 forbidding the display of icons in churches and public places throughout the weakened empire.

Protestant reformers of 16th-century northern Europe however, who had little direct experience with Islam, were seized by the same suspicion and determination to remove figurative sacred art. Many Protestants further claimed that pictorially representing Jesus’ mother, his disciples, martyrs, saints and angels fostered worship of their images as cultic mediators between God and man. Thus any veneration of saints was opposed, making their representations a double taboo. This left only the image of a naked cross as a badge of reductive purity. Washed of representations of the “express image of His person” as St. Paul calls God the Son, the familial gave way to the mechanical, the disengaged and disinterested deity of the Enlightenment.

Former Dominican Monastery Church in the Principality of Orange, France, stripped of its adornment and transformed to a Protestant assembly.

The dangerous power of images

The accusation of idolatry weighs heavily upon the province of sacred art, not because of Islamic and Protestant doctrine but because it presumes to make images of the divine. And there is so much of it to be reckoned with. Practically the whole of late antique and medieval art, east and west, sought to pictorially respond to the question Christ posed to his disciples: “Who do you say I am?”

The iconoclasts’ anxiety that the image is worshiped as an embodiment has a logic that is not easily overcome, hence the perennial appeal to obliterate. The common dread is that the beholder cannot be trusted with the power of images.

To illustrate how entangled this issue is, we recall the deeds of righteous King Hezekiah (715 BC):

He removed the high places, and broke the pillars, and cut down the Asherah; and he broke in pieces the brazen serpent that Moses had made; for unto those days the children of Israel did offer to it; and it was called Nehushtan. (2 Kings 18: 4)

A millennium before Hezekiah destroyed what he contemptuously called Nehushtan, a mere piece of brass, the “brazen serpent” was an image carried across the Jordan into the Promised Land along with the Ark of the Covenant. Its origin was the event in Edom when the Israelites complained against Moses, “and God sent serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died.” (Numbers 21: 6)

And the Lord said unto Moses, Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole: and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he looketh upon it, shall live. And Moses made a serpent of brass, and put it upon a pole, and it came to pass, that if a serpent had bitten any man, when he beheld the serpent of brass, he lived.” (Numbers 21: 8, 9)

Though the bronze figure was given as a provisional sign of God’s deliverance, a place-keeper as it were, it was destroyed because the “children of Israel did offer to it” as an idol.

The context of Hezekiah’s action was resistance to what the Hebrews had experienced during their 400-year exile in Egypt bombarded with of images of Anubus, Horus, Isis and at least 80 other deities. Returning to the Trans-Jordan plateau and highlands of the Promised Land, they were re-immersed in the ubiquitous Canaanite, Phoenician and Philistine images of Dagon, Ba-al, and Moloch. Added to that swarm, though centuries later, was the pantheon of Mesopotamian idols that the Israelites encountered during their three Babylonian deportations: 605, 597 and 586 BC.

Jesus Christ, however, interpreted the image as a symbol of Himself:

And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life. (John 3: 12-15)

The image of the bronze serpent did not depict the human physicality of Jesus of Nazareth; it pointed to his office as the Savior of the world. Speaking of his crucifixion, Christ completed the meaning-making: “And I, if I be lifted up from the earth, will draw all men unto me.” (John 12: 32).

Preaching the Gospel in the Midst of Idolatry

The Greco-Roman culture into which St. Paul and the Apostles carried the message of God Incarnate was similar to that into which Joshua bore the Ark of the Covenant across the Jordan. The scale and profusion of temple ruins devoted to Artemis in the cities of Anatolia where Paul, Barnabas, Timothy and John Mark made missionary journeys – Ephesus, Pergamum, Pamphylia, Iconium, Philadelphia – indicates their erection and upkeep would have cost billions in modern terms of revenue.

All municipal and rural life orbited around the worship of graven images, not only those of the imagination that were laterally equivalent to pagan deities in surrounding layers of civilizations – Greek, Hittite, Scythian, Babylonian and Egyptian – but also images of emperors. Before official and typically posthumous deification of emperors, statuary portrayed the Caesars as triumphant generals in military uniform or heads of state in ceremonial purple and laurel crowns. But deified Caesars were rendered naked and athletic in likeness to Apollo, Hermes and Zeus in order to designate honorific rituals required before their images.

It was in this setting that the apostles strove mightily to overcome the misdirected worship of idols residual in converts from paganism to Christianity.

As concerning therefore the eating of those things that are offered in sacrifice unto idols, we know that an idol is nothing in the world, and that there is none other God but one … Howbeit there is not in every man that knowledge: for some with conscience of the idol unto this hour eat it as a thing offered unto an idol; and their conscience being weak is defiled. (I Corinthians 8: 4-7)

Though St. Paul declares, “we know that an idol is nothing in the world, and that there is none other God but one,” he reminds us “there is not in every man that knowledge.” In saying that “idols are nothing in this world,” St Paul does not say that the honor given to idols is nothing. He warns that the deference, if not reverence, given to idols is assigned to demons and has the peril of defiling the conscience:

For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places. (Ephesians 6: 12)

In the debate of the Council in Jerusalem (AD 50) over what was necessary to require of Gentile converts, we see how the Apostle Peter responded when “there rose up certain of the sect of the Pharisees which believed, saying, that it was needful to circumcise them, and to command them to keep the law of Moses.” (Acts 15: 5) Peter admonished the believing Pharisees saying, “Now therefore why tempt ye God, to put a yoke upon the neck of the disciples, which neither our fathers nor we were able to bear?” (Acts 15: 10)

But when St. James, the first bishop of Jerusalem, ruled on the matter his cautionary focused on the jeopardy of idolatry. “Wherefore my sentence is, that we trouble not them, which from among the Gentiles are turned to God, but that we write unto them that they abstain from pollutions of idols, and from fornication, and from things strangled, and from blood.” (Acts 15: 19-20)

“Unto this hour,” the power of images is perilous. The place of images in civilizations is never neutral.

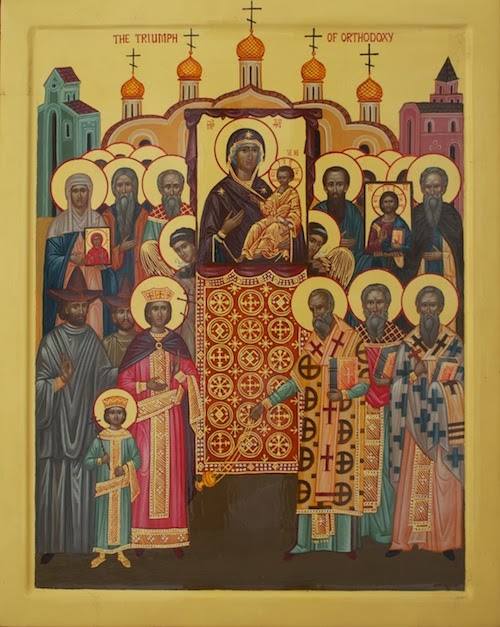

The Triumph of Orthodoxy

If iconoclasm is resilient, the more so is iconodulism. The inspiration to represent heavenly things is not to fabricate images that serve as gods or as mediators between God and men. It is to glorify Him in whom God made Himself tangible as “the brightness of his glory.”

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon, and our hands have handled, of the Word of life … declare we unto you. (1 John 1:3)

Even so it took a century of blood for the Seventh Ecumenical Council (the Second Council of Nicaea), presided by Patriarch Tarasios in 787, to formalize a statement on the efficacy of icons. The Council drew upon the wisdom of St. Basil the Great (330-379) who succinctly made clear that it is the persons represented in icons and not the icons as objects that are revered: “The honor given to the image is transferred to its prototype.” (Letters on the Holy Spirit, 18)

St. John of Damascus (c. 675 or 676 – 749), who was still living when Emperor Leo III ruled against the display of icons, wrote the definitive “Three Apologetic Treatises against those Decrying the Holy Image.” This passage from “On the Divine Images” (1:16-17) is one of St. John’s most famous statements on why the use of icons is not idolatry.

But now when God is seen in the flesh conversing with men, I make an image of the God whom I see. I do not worship matter; I worship the Creator of matter who became matter for my sake, who willed to take His abode in matter; who worked out my salvation through matter. Never will I cease honoring the matter which wrought my salvation! I venerate it, though not as God.

Portions of the Proceedings of the Seventh Council are read on the First Sunday of Great Lent, called “Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy.”

We define the rule with all accuracy and diligence, in a manner not unlike that befitting the shape of the precious and vivifying Cross, that the venerable and holy icons, painted or mosaic, or made of any other suitable material, be placed in the holy churches of God upon sacred vessels and vestments, walls and panels, houses and streets, both of our Lord and God and Savior Jesus Christ, and of our intemerate Lady the holy Theotoke, and also of the precious Angels, and of all Saints. For the more frequently and oftener they are continually seen in pictorial representation, the more those beholding are reminded and led to visualize anew the memory the originals which they represent and for whom moreover they also beget a yearning in the soul of the persons beholding the icons. (Proceedings vol. 11, pg. 719)

Imagery and substance

On the one hand there is an authentic activity of the beholder that St. Basil described, and the 7th Council augmented, which is not idolatry. On the other, the chore of defending the reverence of icons against the charge of idolatry is not simple. Both the holy icons and pagan idols are man-made objects that depict the revered. If the “rulers of the darkness of this world” are real powers to be wrestled with, what is it that separates the veneration of holy icons from the worship of idols?

It is the certainty that the depicted is the “one Lord Jesus Christ, by whom are all things, and we by him.” The holy icons are so called because of who they proclaim God is.

This is true of all the Holy Icons, whether the subject is saints, angels or events. Every icon testifies to the reality of our Incarnate Deliverer. Every icon repeats Simon Peter’s answer to Jesus’ question, “Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God.”

The Orthodox worshiper’s experience before the holy icons is not idolatry, either in the sense of worshiping “nothing in the world” or worshiping the material substance of their composition. It is rather the rightful response to the persons the icons direct prayerful attention. In honoring the images of holy persons there is no distance of time and place between persons beholding and beheld, only the assurance of the lively presence and encouragement of those who “have fought the good fight and received their crowns.” The icons “beget a yearning in the soul of the persons beholding the icons” to emulate the example of those who by their holy lives tangibly published the presence of Him who draws all men unto Himself.

St. Basil makes a touching analogy about the role that images serve as an instrument for turning the heart toward following the examples of righteousness portrayed in the sacred art of the icons.

Both painters of words and painters of pictures illustrate valor in battle; the former by the art of rhetoric; the latter by clever use of the brush, and both encourage everyone to be brave. A spoken account edifies the ear, while a silent picture induces imitation.

(Quoted by John of Damascus in “Against those who attack divine images”)

Save

Save

In other words… if a bear takes an icon out into the woods where no human eyes will ever see it again, is it still an icon? 😉 But seriously.

Does the icon first touch upon our senses, thus prompting the idea/remembrance of the depicted, and is it through the idea of the depicted that we make contact with the depicted? Or rather, does the icon immediately connect us to the depicted via several/all faculties of being? If the icon immediately connects us to the depicted, this is where our use of it is similar to the pagans’ use of idols (I am not opposed). The only substantive difference being that pagan idols are used to connect to suspect spiritual forces, right?

But if the icon connects us to the remembrance (the idea), and this remembrance is what connects us to the depicted… then even though the bear took the icon out into the woods, I can still venerate it mentally from here. ;P

Thoughts?

You pose an interesting question, Baker. I would say that within their appointed setting, that is within the environment of worship – corporate prayer or solitary – the icons serve as an invitation to the beholder to enter into a relationship with the depicted. There is, of course, no guarantee of the beholder actualizing a relationship through prayer and worship of the depicted. The bear that took the icon into the forest may be likened to the museum-goer viewing an icon exhibit and vacillating between finding the object beautifully decorative and strange. The piece of painted piece of wood is itself inert; it cannot automatically elicit a response of worshiping the depicted that is not already latent in the heart. The difference between a response to an icon of Christ and a carving of Dagon is what the image points toward. In the latter example, demonic forces. Only those who love the Very Christ depicted in the icon will give respect to the object bearing His image. And that respect, reverence, is directed towards God.

Florovsky notes that, far more than any Islamic influence, the iconoclastic movement was informed by certain tendencies in Origenism and Neo-Platonism (and of course the iconodules drew on different tendencies within the same tradition).

Simply put, an idol is the representation of a false god, whereas a christian sacred image (crucifix, icon, mosaic, painting, statue) is a representation of the true God Jesus Christ, of His Holy Mother, of His Angels and Saints. To make and venerate images of those we love and venerate is natural to all of mankind: christians too are men, who can come to the knowledge of the invisible, the spiritual only through the bodily senses. The difference lies in the Object of our love and worship, not in the means. ”Homo naturaliter christianus” (”Man is naturally christian”). All of man’s activities can be christianised and sanctified. Saint Augustine wrote, that christians must reclaim from paganism and dedicate to Christ all that is useful, good and just, even the whole world. Especially the art of imagemaking, for God the Son Himself is the Image par excellence, and man is made in the image of God: what then can be more christian than Images?

I have a slightly different reading of the brass serpent than you do. Jesus does not identify himself with the fiery serpent of Moses’ staff; what he says is that as that serpent was lifted in the wilderness, so he too must be lifted up.

It would be strange for the Lord to adopt the serpent as a symbol of himself. Rather I think what is going on in the Moses story is this: Israel is tormented by demons (serpents); by the power of the Cross Moses shows Israel that the chief of the demons (the fiery brass serpent) is overcome; through that display those who are tormented and being slain by the demons are healed. This makes more sense, as it is on the Cross that Satan is overcome.

If the serpent was an image of Christ it would also be strange for a righteous King like Hezekiah to destroy it. Rather I think the brass serpent was kept as a memento of Moses’ display of the Cross’ victory over the demons; in worshipping it Judah fell into idolatry (straight idolatry: devil-worship); but Hezekiah knew that the Devil had no real power and so destroyed it as a mere piece of brass.

All that being said I really enjoyed the article! Thanks for publishing it!

Thank you, Sean, for these comments. There is a lot here to discuss. The action of King Hezekiah and the words of our Lord are, of course, not a one-to-one correlation of identity. They are not even identity by typology. They are identity by analogy, even a shadowy and disturbing one of snakes in the desert.

I like your phrase, “a memento of Moses’ display of the Cross’ victory over the demons.”

But I think this still leads us back to the central point I tried to make; images in icons point to the actual: Very God of Very God, not demons counterfeiting as gods. To worship the image is to embrace many levels of delusion, including a lack of common sense.

Hezekiah destroyed what had become a tool of this temptation, obviously one of precious provenance to descendants of the Exodus experience. By extension he also ruled against pagan accretions from surrounding mythologies such as the staff of Asclepius that blended comfortably with Israel’s misdirected offerings to Nehushtan.

What Christ’s declaration did was to reveal his salvific mission in the most dramatic terms of Israel’s group memory. We can go on for days exploring metaphors of snakes, poles, and brass. In its apotheosis, the foundation of the analogy is just as you said, Sean. It is in what Moses did, not the instrument: “as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up.”

The ivory carving used as an illustration in the article compresses Christ’s decent to hell and his resurrection, even his ascension symbolized by snakes and dragons beneath his feet. It is he who is held up and the demons crushed.

If we see serpents as an image of death rather than only an image of demons or Satan, then it is not so odd to think that Christ compared himself to a serpent in the sense that he became “sin”, in the sense that he united himself to death in order to save us from death.

If we look at the symbols of serpents in the story of Moses, the serpent changing into a staff, then a staff to a serpent, then a hand becoming sick and then well again, then a serpent on a staff (Nehushtan) which heals from the poisonous serpents, the pattern is pretty clear and we cannot only think that serpents are only an image of demons. For more on the relationship between Christ and the bronze serpent, or Christ and serpents in general, one can read my article on the subject.

The Serpents of Orthodoxy

Jesus Christ did approve of holy images, for He Himself, being God, commanded the hebrews to make images of the Cherubim for the Temple in Jerusalem. It is also a known fact that jewish synagogues which have been excavated were decorated with all kinds of images. What was forbidden to the hebrews was to make and ADORE images of false Gods, and to make an image of the true God, as He had not yet become incarnate. Our Lord’s assumed Sacred Humanity is an Image of the invisible Godhead, a subject which Saint Paul several times expounded in his epistles. Our Lord accepted worship whilst alive and – if we are to believe the Apocalypse, He – the Lamb upon the Throne – accepts worship in Heaven. Radical iconoclasm is islamic in origin, and this was much later taken up again by Calvinists and Zwinglians during the Reformation: Luther, nota bene, was not an iconoclast. Finally, Our Lord Jesus Christ approves of icons because His Church – the undivided orthodox catholic Church – has always approved and blest their usage. And Christ cannot be divided from His Body, the Church.

Yes, Albertus, the part that illustrative painting played in the adornment of Jewish synagogues is evidenced by a huge store of examples going back to the Talmudic period that have recently been excavated in Northern Israel. Similarly, excavations of a synagogue (erected circa 245 AD) in the city of Dura-Europos in Syria reveal a worship space filled with depictions of major figures from sacred history such as Moses, Elias (Elijah) and David, as well as lessons from Ezekiel and Daniel. These panels, stylistically influenced by Hellenic and Roman models of mythical heroes, celebrate the encounter of real persons with the presence of God. Clearly, the Christian Church inherited this tradition of artistically populating Her places of worship with images that describe past events as eternally present. In fact, the oldest known Christian paintings are probably those of a house church also found in Dura-Europos.

The objective of both Jewish and Christian art was instructive but also experiential. The Jewish Dura-Europos murals of the infant Moses rescued from the river, his encounter with the burning bush and the Exodus more than reminded the community of its origins; they built faith and reliance on God for its survival. Beyond this, the text of these images proclaimed the promised appearance of another “Deliverer”, an archetype of Moses who would usher in an everlasting and imperishable kingdom. The same subjects in Christian iconography identify this Deliverer as Jesus of Nazareth, the Messiah of Israel.

The painting of Samuel anointing David as King of Judea also had a messianic dimension for Jews of the Diaspora. Prophesy concerning the youngest son of Jesse, the shepherd poet, encouraged hope for restoration and salvation.

The mural of Ezekiel’s vision of the tombs opened and the dry bones in-fleshed with life again depicts the general resurrection at the last judgment. The text of the valley of dry bones (Ezekiel 37) is read annually in Orthodox Christian churches everywhere during the early hours after midnight on Pascha (Easter) morning. The reading is treated as a prophesy of Christ’s decent to Hades to free Adam (mankind) from the prison of death.

Orthodox Christians churches have more in common with the interiors of third century Jewish synagogues than with most Christian denominational places of worship today, which are mostly devoid of images. Jewish retreat from depicting the human form seems quite rapid, however, after the first few centuries of Christianity. While depictions of animals, cherubim and scenes of nature continued minimally, Jewish iconoclasm for representing persons may have been related to the enthusiasm of the Early Church for artistically proclaiming the revelation of the Word become Flesh in the person of Jesus Christ. Whether reactionary to Christian iconography or a development within Judaism toward pure symbolism and decorative script along the lines of Islam, there was a span of several centuries when the imagery of salvation was common to both Jewish and Christian places of worship.

Thank you for this! Very beautifully and clearly set out.

The discussion at hand is not whether we can quote directives from the “red letter” version of the gospels. It is about how Christ made use of existing images and symbols to reveal Himself, which thus set a precedent His Church emulated. An interesting way to explain the efficacy of iconography in Christian worship has to do with the use of symbols. Symbols are very powerful tools in every culture used to compress and communicate information in order to expand it. The nimbus, for example, symbolizes the theosis of persons represented in the icons. The special characters Ο ωΝ (omicron, omega, Nu) within the nimbus of Christ symbolically identify Him with the name of God spoken to Moses from the burning bush at the foot of Mount Horeb. When spelled out the O wN, as found in the Septuagint (Exodus 3:14), translates variously “I AM”; “The Existing One”; or “He Who Is.”

Symbols can move from coded form to the precise, as in the case when Christ reveals Himself as the deliverer symbolized by the bronze serpent. Iconography is sometimes called upon to assist this revelatory process of reforming provisional symbols by graphically transforming them into a vivid and direct statement of the symbol’s intent. Canon 82 of the Council of Trullo, the Quinisext Council (AD 692) so directed:

“In order therefore that ‘that which is perfect’ may be delineated

to the eyes of all, at least in colored expression, we decree that the

figure in human form of the Lamb who taketh away the sin of the

world, Christ our God, be henceforth exhibited in images, instead

of the ancient lamb, so that all may understand by means of it the

depths of the humiliation of the Word of God, and that we may

recall to our memory his conversation in the flesh, his passion

and salutary death, and his redemption which was wrought for

the whole world.”

Since the icons reveal to us our living Lord Jesus Christ and those who dwell with him and in him, they are not graven images or likenesses, and there is no idolatry involved in venerating Him through them. We already dwell in the Kingdom of Heaven and the icons remind us whose company we keep and help draw us into that Kingdom where we already dwell, and where we will come to dwell at the Resurrection. God is the Lord and has revealed Himself to us, first of all in the flesh and blood of his son, our Lord and God and Savior Jesus Christ, the first icon of the Father and the original of all icons.