Similar Posts

The following is an interview with Romanian master iconographer Ioan Popa. He’s one of the leading representatives of the contemporary icon revival in Romania, focusing in both panel and monumental fresco painting. Our conversation touches on his artistic development, aspects of the professional training of iconographers in Romania and the challenge of creative engagement with the Tradition. We would like to express our gratitude to Fr. Dragos Giulea, rector of St. Benoît de Nursie Church, Montréal, QC, for his work as translator of this interview.

***

Fr. Silouan: First of all, thank you Ioan for giving OAJ the opportunity to interview you. The idea passed through my mind a while back but the language barrier prevented it. So I’m pleased we’ve found a way to get around it to make it happen. Let me begin by asking you about your training as an iconographer. Did you study painting prior to your involvement with iconography?

Ioan Popa: I would like to thank you, too, for your interest and curiosity shown to an iconographer belonging to the Romanian sphere. My beginnings in the amazing world of the icon are due to the spiritual background in which I grew up and in which I was educated. Born in a typical family, I had, however, a grandmother of great inner strength; she was the mother of twelve children, and two of them became monks. They were the ones who opened my way to the Byzantine icon when I was still a child. We are talking about the 80s, in full communist times, when the regime was, nevertheless, allowing monasticism, in a restricted sense, the right to liturgical service and even the possibility of building and painting churches. In their monastery, in Transylvania, I had the opportunity to discover, for the first time, the special ambiance of the fresco, with everything specific to it, from up there on the scaffold. It was the interior of a new church painted at that time by the iconographer Grigore Popescu.

Then, high school followed and a period of training at the icon studio of Râmeţ Monastery with the nun Maria Jurj, where I discovered the first albums of Byzantine models and some fine brushes and paints brought to the country immediately after the change of the communist regime in Bucharest. However, the fundamental thing was the spiritual guidance I received at the time, and the education in good taste and good choice of models.

Towards the end of my studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bucharest, at the department of Mural Painting, I met my future wife, Camelia, my younger colleague in the same department, and we decided to put at the service of the icon and the Church all the artistic skills and knowledge acquired academically. This mission was first offered to us not in our country, but in Southern Italy, in a Catholic region where several parish priests wanted to recover the local Byzantine tradition of the first Christian millennium. There I finished my first frescoes and important icons, I discovered people who appreciate and support this artistic approach, and a very rich and vast iconographic tradition, amazingly preserved and valorized; I also understood the importance of respecting and recovering the spirit and the specificity of local tradition.

Together with Camelia, we have become a team which is constantly looking for theological themes and solutions, as well as for stylistic, compositional, and expressive formulas for each particular place and church. I have to say this about my wife, because she has been artistically less visible for the past seven years when she has also accomplished another work full of responsibility as the mother of three wonderful boys. However, after several works done in different countries, we made the decision together to return to Romania and serve the community and the Church at home.

Design for fresco in the Sanctuary of Monte Sant’Angelo, Mount Gargano, Italy, by Ioan Popa (b.1976) and Camelia Ionesco-Popa (b.1979), 2003.

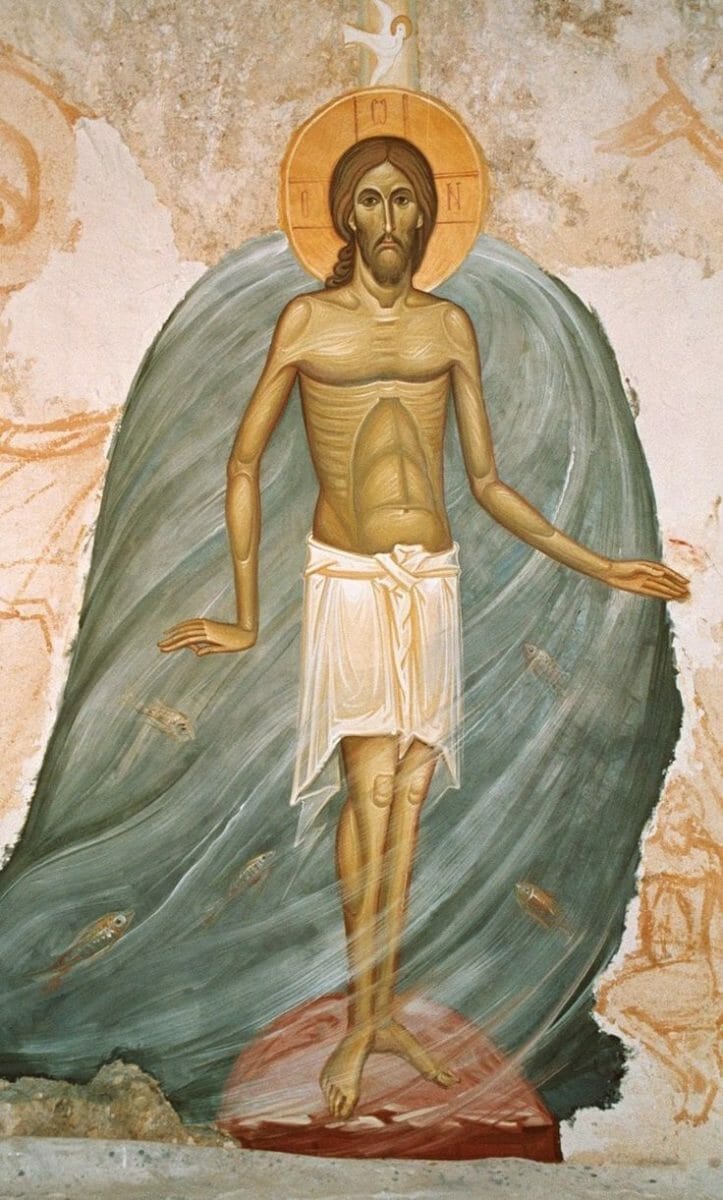

Ioan Popa and Camelia Ionesco-Popa, “Baptism of Christ,” Fresco, 2003. Sanctuary of Monte Sant’Angelo, Mount Gargano, Italy.

Fr. Silouan: What are the most important professional educational programs available for the training of iconographers in Romania right now?

Ioan Popa: We need to differentiate between two kinds of activities, between icon-painters and fresco-painters. There is, in general, a multitude of formative ways, both complex and very dynamic. The segment of the church painters is the most representative in Romania and their education follows the traditional way, through direct experience practiced on the painting construction sites.[i] Teamwork makes it possible to pass on technical procedures and theoretical notions from the oldest and experienced ones to the less skilled beginners. It should have been good to talk about a master-apprentice relationship, as it happened in the Middle Ages, but only in the last decade have there been some real preoccupations and attempts toward such goals. Some teams, belonging especially to the younger generation, are characterized by a special communication among members, both in terms of their specialization and spiritual communion.

The discipline of church painting has also been part of the iconographic fervor Romania has experienced in the last 20 years, with an administrative mechanism generated some 60 years ago in the Romanian Patriarchate and called the Church Painting Commission. All those who want to embrace church painting have to be first licensed by a committee composed of three academic priests, three painters with vast experience, and, more recently, an art historian. It is necessary to have a two-year apprenticeship period in an icon studio or painting construction site with an experienced painter who is already licensed. At the end there is an exam of drawing from memory: a human figure and a scene from the Feasts of the Savior. There are two more years of specialization, usually with the same licensed painter, and a final test that consists of a theme performed directly on the wall, usually a complex scene; then, a theoretical exam of dogmatics, art history, and a technical test consisting of several icons and a church iconographic project in a section. At the end, the candidate gets a grade expressed in degrees, and then, depending on the number of painted churches and the iconographic quality, they advance in degree. This allows the one with more degrees to access important works in the monasteries or cities of Romania and the diaspora.

So most of my guild colleagues have begun the study of iconography in this context, and then, on the way, with their own possibilities, the practice of drawing, of technical aspects, and the intense study of the old masters of Byzantine painting. This is done especially after reproductions and photographic documentation, following study trips to the ancient churches of Serbia, Macedonia, and Greece.

To this process of training are added some special departments, called of Sacred Art, opened in the Faculties of Theology in the main Romanian cities or Metropolias. These are institutional settings that provide an in-depth theological study as well as technical and artistic training. However, the specialists are in most cases not chosen from the most representative iconographers of the moment, who are not supported or promoted, and the final training is not one of higher level.

Another segment of the future iconographers comes from the graduates of the Academies of Fine Arts. They are already well acquainted with the notions of drawing, composition, and plasticity, and later approach the icon more creatively and artistically.

Finally, an appreciable number of icon-painters, some of them even monks painting only icons of good quality, generally have recourse to the old Byzantine tradition or old Romanian painting. A significant number of Romanian iconographers, in the last 12-14 years, have managed to get training in close collaboration with two Romanian monks living on Mount Athos, fathers Haralambie and Iacob, who strongly support the creation of authentic Byzantine icons, of excellent complexity and technical quality. The young generation has also a fruitful collaboration with the monk Elijah (Ilie) Dantes, active at a monastery in southern Romania, and who developed a style following the Palaeologan School. Another group of icon and fresco painters has been trained in Cyprus under the guidance of a Cypriot Athonite monk, Father Dometios.

Fr. Silouan: Who would you say among your professors and fellow students have played an influential role in your artistic development?

Ioan Popa: As I mentioned, in what concerns the evolution and deepening of the artistic approach, which is also significant in the iconography of our times, my wife has permanently played a key role. She is a very talented artist with a valuable academic background. Together we are trying new ways of artistic expression and theological message. Generally, the liturgical space, the wall designed for iconography, gives you the tone and suggests certain stylistic solutions or directions. You just have to discover its features, analyze them correctly, and follow them. This will generate diversity in your approach without making, over time, a repetitive, cliché painting.

Additionally, an important role in my formation as iconographer was also played by all colleagues in the field, either younger or older, either from the country or from other areas with iconographic preoccupations. I have learned as well indirectly from their experience and searches. Many times, after learning the basics of Byzantine painting, it has been helpful to see a direction or trend followed by others, to analyze and evaluate it critically, and then decide if it is necessary to follow the current or to consider that another iconographic expression is needed. In so doing, I have saved a lot of time and energy.

Among my masters, a true contemporary church painter is Master Grigore Popescu, a very creative fresco-painter, with a chromatic palette of great refinement and always surprising, who made a stylistic synthesis that belongs to the whole Byzantine areas as well as the native context, but especially unique by new compositional formulas and a very expressive decorative background. Through the courage of his approaches and the unusual artistic solutions, he has influenced the whole generation of young fresco-painters.

However, strictly regarding the artistic, aesthetic, or plastic component as well as the iconic synthesis, I have recently learned a lot from a venerable contemporary Romanian icon-painter, Master Sorin Dumitrescu. I can say that it was an authentic master-disciple relation in the context of a partnership that preceded the painting of the Noetic Ark church in Alba Iulia. It was an intense experience of almost half a year in which, as in a real lab, we were looking for numerous solutions for the plastic and theological expressions of a very daring contemporary iconography. Unfortunately, things could not continue, but we received, as a result of this collaboration, the credit of an iconography made with more daring and creativity, with a much wider and more assumed study of the liturgical text, and a very free way of treating the surface of the layer of color.

Fr. Silouan: What’s happening in Romania right now when it comes to the icon painting revival? Is there a core group of iconographers, theologians and scholars setting the tone?

Ioan Popa: In the last 10-20 years we have being witnessing in Romania the rise of an impressive number of icon-painters and fresco-painters. All this is due to the large number of churches built throughout the country, especially in every town with areas of apartments built in the communist period and, of course, not provided with places of liturgical worship. Then many monasteries and hermitages were opened as well as churches in each hospital or military unit. These churches also require an iconographic garment and icons to be placed on iconostases and elsewhere. So there is an annual average of 30 authorized people, more or less prepared. In most cases, churches are painted in the fresco technique, which is very complex and demanding. It is passed down from generation to generation and further taught with a lot of responsibility because it is the safest and most resistant technique tested so far on a parietal surface.

In this sense, we have a privileged situation, but there are many things to be approached and solved in what concerns the stylistic solution and the perception of the final ensemble. Many liturgical interiors are still visually too loaded, sometimes with a strident, commercial chromatic, in which the painter and the patron approach surfaces with a mentality more concerned with covering each meter of painting and justifying its payment than with joining the iconographic message to the Liturgy and Church chanting. The emphasis is placed on mechanical reproduction, rather than an authentic discovery and experience of Orthodoxy.

We can say that there are several delineated venues, which are rather good takeovers and stylistic reproductions. There are also some more personal expressions derived from these takeovers from Tradition. However, the lack of a general tone generated by specialists in the field and theologians really leads to the coexistence of an obvious diversity of expression in Romania: from copying with great fidelity either Manuel Panselinos or the contemporary Greek school to taking over scene by scene Macedonian and Serbian paintings, from the ultra-repeated models of the Constantinople and Thessaloniki Schools—understood as the ways of learning correctly and responsibly directly from the great masters—to syntheses and stylizations of the peaks of Byzantine painting and very responsible takeovers of the old Romanian school painting.

In terms of content and problematic of some assumed directions there is still no official involvement from the Church institution. There is a need for a critical analysis and for written works on what Romanian iconography has meant in the last 50-60 years since it has gradually returned to a Byzantine type of iconography and, however, has generated enough works of reference, both icons and painted churches. A good start is the preoccupation of the Romanian Orthodox Patriarchate to launch themes, conferences, and even a series of competitions related to the national specificity in church painting.

Fr. Silouan: Tell me about the Iconari in Otopeni symposium projects? Which organizations, periodicals and international conferences would you say are leading?

Ioan Popa: The 5th edition of this project has been recently completed. Its first intention is to show the truly authentic values of the Romanian young generation of iconographers. Another component is that of working together, learning from one another, without secrets, amongst painters, but also with the audience who need a visual catechesis in all this assault of advertising images and other images of poor quality. Another goal is also to put in a catalog the testimonies of those who paint today, to understand their ministry done through painting, and also to put together all those characters who in the past were able to build those beautiful churches of their time: the architect, the painter, the sculptor, and the theologian, all of whom today unfortunately work separately.

This year, we held an international edition with iconographers of nine countries. It was a true celebration of the universal icon in all the diversity and cultural richness that each participant brought. It is extremely important to have a broad comprehension of contemporary iconography that is generated by other causes than Byzantine and post-Byzantine iconography.

Regarding publications, I believe that your website www.orthodoxartsjournal.org has the broadest and most objective view of contemporary iconography, created for other reasons than the specific activities of an Orthodox country that may discuss only domestic, national questions, or belonging to some specialized groups. The fact that you have the interest to put together architecture, painting, music, and theory is a very necessary perspective that gives liturgical meaning to all iconographic concerns. I think there are many other active communities that expose, publish and discuss, in Russia for instance, especially at the Sergiyev Posad Academy and the Artos Association, but few things are translated, which is why we do not know much about this sphere. However, some specialized information is available in virtual venues, which connect us to other iconographic realities and preoccupations of our time.

Iconari in Otopeni Symposium participants at work. Iconari in Otopeni is an an event, held since 2013, featuring an open workshop, exhibition, lectures, meetings and discussions with young icon-painters from Romania and other parts of Europe.

Fr. Siloaun: What are the main theoretical and practical questions being addressed or discussed among Romanian iconographers today?

Ioan Popa: The year 2017 was declared by the Romanian Patriarchate an anniversary dedicated to the icon-painters. There were countless audio and video interviews with the icon producers in our country. Now we have testimonies about our own experience, but there is still little dialogue and theoretical questioning. For most iconographers, the basic concern is to connect to the Byzantine, traditional element, of learning and retrieving a lesson and a painting school dysfunctional for many centuries. The method is accessing the old models, either by copying or by understanding and learning a church painting language that belongs to different centuries. At the theoretical level there are individual questions about how far today’s painter may understand and paint at the level of Byzantine masterpieces, such as the painting of Chora or Constantinople; or preoccupations regarding the simplification and adaptation of a certain traditional heritage to the sensitivity of the contemporary believer and the society we live in. Other preoccupations—regarding the trends, the processing of the prototypes’ data, solving the assemblies, and dropping the dark backgrounds by introducing bright shades—are still questions in their incipient stages. But the grace of the Holy Spirit has been a permanent worker in His Church and will fulfill our quests where we have no understanding and answer. The iconographer has the duty to “guard the good treasure entrusted to you, with the help of the Holy Spirit” (2 Tim. 1:14).

Ioan Popa, The Samaritan Woman (St. Photini) with Christ at the Well. Fresco in the Noetic Ark Church in Alba Iulia.

Fr. Silouan: Your work, although very traditional in ethos, also demonstrates awareness and what seems to me a conscious engagement with some aspects of Modern art. How do you see the interplay of traditional iconography and the developments of 20th century Modern painting? Is there room for innovation without compromising Tradition?

Ioan Popa: Regarding the personal artistic approach, it is necessary, I think, to become aware of the cultural context in which this ecclesial painting emerged. It has to be the expression of the entire ecclesial tradition of 2000 years, and not of a particular period taken as the pinnacle. Yet, it is unnatural to ignore the contemporary artistic palimpsest and not to resort to greater simplicity of the means of expression, to the essential form and iconic message, to the way the icon holds on to you and speaks to you in the rush in which the course of this society places us. The Byzantine stylistic approach has to be reformulated and translated to the conditions in which we are no longer Byzantine, but rather live in full-fledged postmodernism and globalism, times in which the image has an overwhelming impact and travels at a dazzling speed.

A series of questions arises: How do we offer, today, the icon to the Church as a representation of the creation transfigured by uncreated light? How do we make it to be perceived as a foretaste of the world to come, a presentation of the invisible? What preparation of our inner life is here implied, and what other understanding must we have, as servants of iconic representations and of the divine mysteries? How much do we have to submit to consecrated models and how much do we need to have a lively and creative dialogue with the Tradition and its texts able to inspire new meanings and themes?

I believe that the answers are present and permanent in the Church, in the midst of our communion, under the sign of the Holy Eucharist, of the Body of Christ that we receive at each Liturgy, through the awakening and care of spiritual personal life, and through them in the acquisition of the Holy Spirit. There is still a need for intensive working experience and discussion on this type of minimized approach of the forms and means of expression, of the essential elements of composition. It is a reconceptualization of traditional language and plastic synthesis that requires an honest redaction related to the artistic activity of our time.

Present culture, even if strongly secular, may mark this new iconographic language. The Byzantine art of every century was actually the expression of the philosophical, social, and cultural factors of the time. Admitting it sincerely, Tradition was a permanent and continuous innovation!

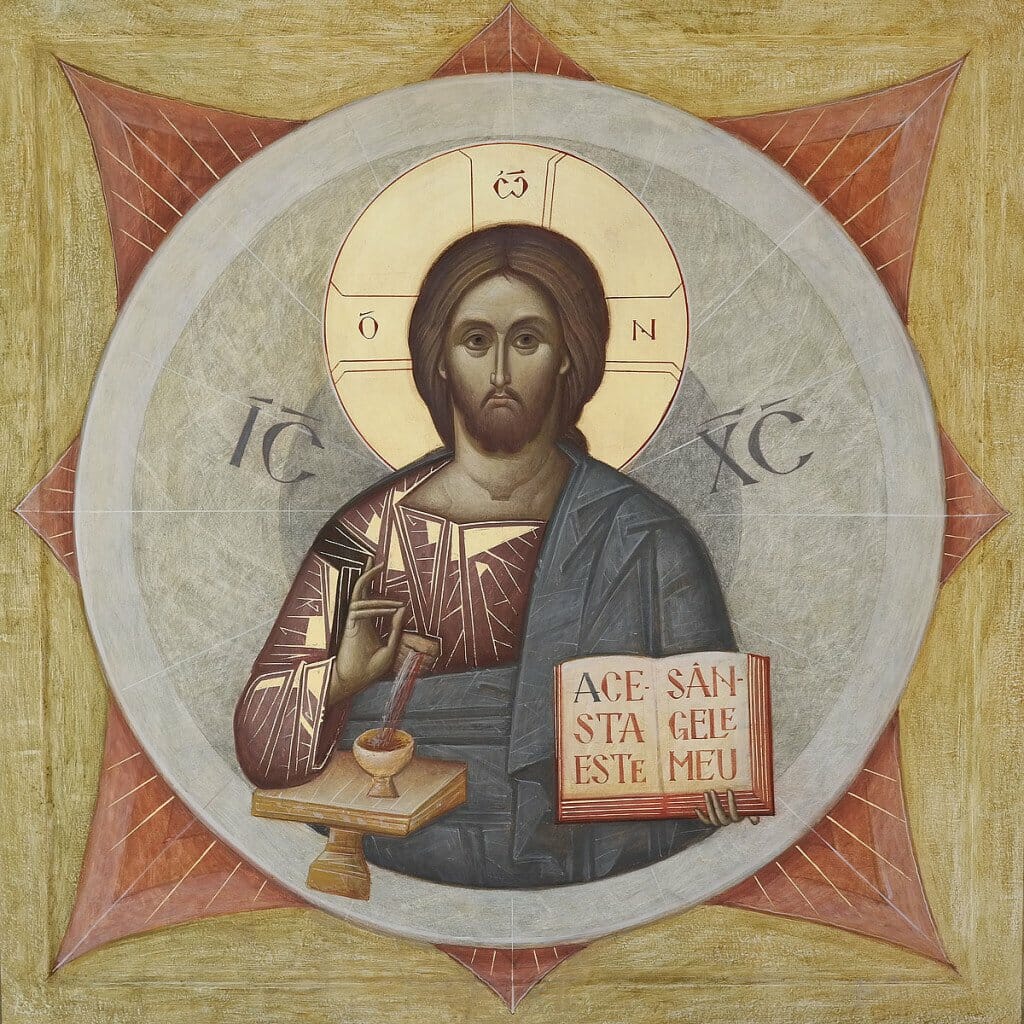

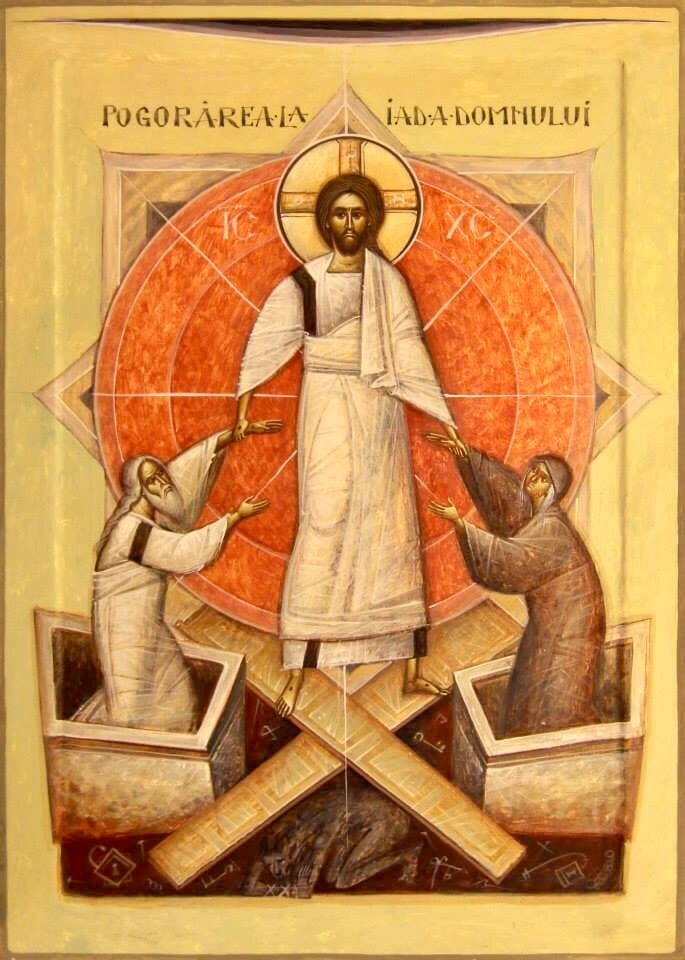

Ioan Popa, Eucharistic Christ. Portable Icon, Egg Tempera.

Fr. Silouan: Tell me about your process. Do you begin with an already resolved drawing which is transferred to the panel? Or do you articulate the drawing on the panel itself organically? How do you avoid the slavish copying of old models?

Ioan Popa: To avoid the close copying of some old models, I refuse to have them at hand. Inevitably I would be attracted to some specially painted details or stylistic elements that are remarkable or very well-known but which would be recognized as belonging to certain periods and schools. Some Byzantine masterpieces have been so much taken over and so well imitated that they have somehow devalued. It would actually become a closed way if I proposed the same venue. I think the main problem is that we are no longer honest when, at the end of our basic training, we make recourse to ready-made solutions belonging to another person with everything that person lived and felt at that time. We do not remain natural. Why so much diversity in the history of Byzantine art as it is, for example, in the representation of the scene of the Nativity? Because they were not so tributary to some models, and they were expressing what they had assimilated at that time through personal experience. Analyzing contemporary iconography, I think this is the great temptation of an iconographer: to have easy access to many models and have the convenience of taking them over easily (even translating them with a projector) without passing through all the stages that the old iconographer has worked on. Those who have a well-developed sense of reproduction can make a performance of this, but they call off their own creativity and their own talent.

Coming back to the approach of painting a church, I place great emphasis on the study of the texts related to the scenes or lives of the saints to be painted. Then I use a vast archive of models I have been collecting for many years. I go especially to manuscripts with mosaic scenes, in which compositions are already clear, and make a synthesis that resonates with the preoccupations of contemporary art and offers a unity of style. I try to clean the image and the composition of the icon of the whole visual and narrative ballast. It follows the preliminary sketches for each scene, then I make again the drawings by joining them together, because many elements that are good on one page get in conflict when joined with other drawings. Ideally, it should follow projects in which all the details are set on the scale and the transposition on the wall would be easier. Often, however, because fresco is a quick-drying technique, the drawing is done with the brush directly on the wall, it is checked, and then the paints are applied.

Ioan Popa, Crucifixion. Egg Tempera on Board.

Fr. Silouan: I’ve noticed that you tend towards sobriety in your palette choices. Your color is never loud yet neither is it simply drab or dull in effect. I guess it can be seen as conveying joyful mourning in a way. What are the formal qualities (color, line, form) that you particularly aim towards in composing an icon? In other words, what is the importance of pictorial abstraction in this process of articulating the content of the work?

Ioan Popa: It is a question of great refinement and subtlety! I was told in school that you may learn the drawing but with the sense of color you are born or not. So, before the church of Alba Iulia I tried to solve the color in a decent and reasonable way, always thinking of myself as a graphic artist, a discipline I also studied. But I tend to think that color sensibility is also visually educated through much contemplation of the old paintings as well as through a sort of fasting from the many shades you can find in abundance at the specialized stores!

The most important part is the spiritual, inner fostering, which then speaks through color. This can express both seriousness and joy in communion with the other. You have to think deeply to whom you are addressing the painting: To you, to your fellows, or to God? If we apply love as an evangelical foundation, I think that we must carefully bend towards the way our fellows feel things. Even though most of the times they are not educated, the love of beauty is seeded in them. And as servants in color we can either alleviate or exhaust them through what we paint; we can send them a message or, worse, confuse them.

So we can use all the tools allowed: concise and powerful visual shapes, a narrow but valuable chromatic palette, gold foil not in excess, dropping frames between scenes in order to let the viewer read them as sequences, a careful balance between full and empty, monumentality, texts developed to replace abusive ornaments, dropping landscape or architectural accessories in scenes, and emphasizing the conception in unity with the rest of the liturgical objects from the interior. I do not exaggerate if I compare the image of today’s icon with a qualitative advertising banner. Practically, both address the same contemporary person in everyday life.

Entrance exterior to the Noetic Ark Church in Alba Iulia,dedicated to Saint Brâncoveni and Saint Joan. All of the icons and frescoes have been executed by Ioan and Camelia Popa.

The foundation stone was put on May 31, 2007 by The Most Rev. Andrei Andreicut, Archbishop of Alba Iulia.

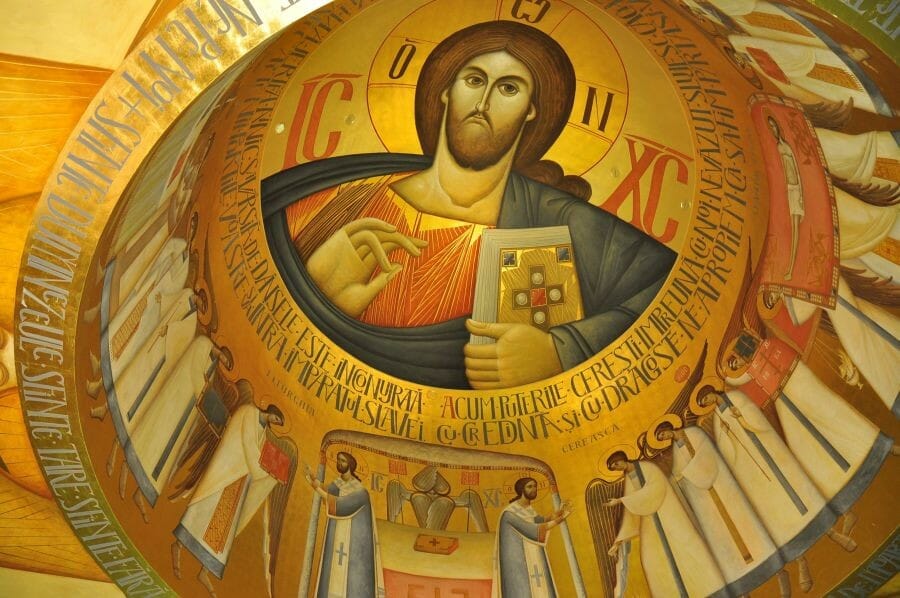

Interior of the Noetic Ark in Alba Iulia.

Fr. Silouan: Does your role in painting the cycle of frescoes for the church in Alba Iulia, designed by the architect Dorin Stefan, stand out as particularly important in your career? Would you say that this project really embodies the positive tension between novelty and timelessness that is possible in liturgical art?

Ioan Popa: The fact that it is a special work is proved now, more than two years after its completion, when we receive a lot of positive reactions from many categories of people who have passed the threshold of this church. It was a wonderful provision and care of God in my life and my wife’s, because, here, through our artistic beginnings in the West, especially in Italy, through all the visual and social experience accumulated there, we came to solve pictorially an edifice unusual to the native Orthodox space. But which I found, in its typology, in the old basilicas preserved in Rome and throughout Latin regions, and also in the provocative and nonconformist contemporary edifices that Western architects propose. Transylvania has always been more open to these challenges, there are Latin influences resonating massively in liturgical painting and architecture, which makes me think that the echo to the early Byzantine elements preserved in Italy can be found in the approach of the Alba-Iulia ensemble.

As a totally private project, there was no official involvement of the hierarchy, and the parish priest Nicolae Jan was the one who managed the entire collaboration with the painter, both in what concerns the liturgical elements to be included in the painting and the theological composition of the key scenes. Thus the project overcame stagnation in approaching the sacred edifices, both architecturally and pictorially, in an endless taking over the old church designs and in fear of innovation. Through the simple and courageous design of the architect returning to a basilica shape that changes into a cruciform one, and the lack of windows within the walls, it was provided a very homogeneous support for the future fresco cycle, being created a true painted rotulus. I have made the most of this rare opportunity and of freedom of expression in order to create a precedent that can be debated and, if possible, emulated. It is an example and proof that, resorting to the archetypes of universal Church art, one may also re-express them indefinitely, thus making innovation possible. The permanent thought was not to resume a previously painted score but to imagine, as far as I can see, the Kingdom of Heaven that I invoke at every liturgy. We have only taken an empty space that was not welcoming at first and transform it to convey this state of atemporality. Although it seems innovative, the painting takes on a category of less accessible models and types of composition, extracted from the ancient Christian and pre-iconoclast Tradition, elements that are unfortunately often associated with the West and erroneously with Catholicism. There is certainly a need for more artistic catechesis to combat visual ignorance.

I think that the painting from Alba-Iulia is a first attempt of this type in a church. It’s a search and concern in formulating the key elements related not to late Byzantine cliché copying, but done through appeal to the essential and minimal in facial expression and especially of garments, by giving up excessive creases and folds. Thus, the evolution of our post- and neo-Byzantine church painting is put in a historical perspective. I do not know to what extent it will create a style in ecclesial circles, whether it will function as a model, but it will surely be well received by the educated as an artistic gesture in itself.

Ioan Popa, Christ the True Vine. Iconostasis of the Noetic Ark Church in Alba Iulia.

Ioan Popa, Theotokos. Iconostasis of the the Noetic Ark Church in Alba Iulia.

Fr. Silouan: Do you have any final words of practical advice to contemporary iconographers?

Ioan Popa: It is necessary in these times for much honesty with what you paint and with yourself. Always take care not to overturn the received talent that is part of your unique personal relationship with God and the experiences and personal confession you make in the midst of your community where you work. The big danger is to imitate or reproduce in order to learn, the convenience, and the ready-made icon. It requires an artistic effort interwoven with a spiritual one, watchfulness, and reverence to Tradition, industriousness and humility as well as a high dose of patience, passion, and perseverance.

I believe that the role of a spiritual father is also essential in enhancing deeper prayer and ongoing spiritual healing. He does nothing but put you on the natural course of Christian life, of involvement in the life of the Church, of joint communal ministry and communion with the Holy Mysteries, with liturgical texts, and ecclesial chanting. The icon should be the living homily we desire at the end of every Holy Liturgy, not the cliché preaching repeated years and years on the same evangelical pericope, no longer able to raise any reaction or living feeling in your soul. It’s key to try to seek and deepen the meanings, symbols, and interpretations of the richness of the Holy Fathers related to the liturgical message, theology being the main cause and source of iconography.

Fr. Silouan: Thanks again Ioan for taking the time out of your busy schedule to answer these questions. I’m sure many will find them very helpful. May the Lord continue to bless your work!

For those who can understand Romanian there is more on Ioan Popa’s work in an Youtube interview.

You can also access more on his work in the Liturgical Art Workshop website which is an extension of the Iconari in Otopeny project.

Notes:

[i] Translator’s note: “painting construction site” refers to any church (either of a monastery or a community, old or new) which is painted and the whole site, with scaffolds, becomes a construction site.

Wonderful interview and beautiful art, thank you!

This is phenomenal. “If we apply love as an evangelical foundation, I think that we must carefully bend towards the way our fellows feel things. Even though most of the times they are not educated, the love of beauty is seeded in them. And as servants in color we can either alleviate or exhaust them through what we paint; we can send them a message or, worse, confuse them.” Such a rewarding read, to the last drop. Thank you Fr. Silouan for making this interview possible.

Good/beautiful work and interview. Thank you! Elena Ene D-Vasilescu

Congratulations Ioan and Camelia, and thank you, Fr Silouan, for asking all the right questions! The Church in Romania seems to excel others in its capacity to nurture trained iconographers and fresco painters who are both highly trained and who also use their creativity in the right way, in the service of spiritual vision. This is surely the fruit of spiritual maturity. May the example of our Romanian brethren inspire us all over the world!