Similar Posts

This is the first of two parts of this article.

I. The Problem

How many Christians believe that the texts of the Old Testament describe people and actions exactly as they were when the events took place? According to such Christians, Biblical stories give us a true and detailed image of the people and events they describe. The relation between the words of the text and the event itself is very close. These Christians read the story and see a “movie,” rather a documentary or a news reel, in their heads. This way of reading Biblical stories is often called literal, fundamentalist, word-for-word, etc. Today, it has a very bad reputation because those who believe in this kind of interpretation often oppose ‘the very bad atheists of science’ to ‘faithful believers who are valiantly fighting to maintain and defend their faith.’ And so, we have all the classical battles between religion and science. Unfortunately, the image we may have in our heads of a particular Bible story and the image of the same event given by modern Biblical scholars are rarely the same. So what do we do?

First of all, we must understand that the question of the relation of Biblical texts to the events they describe has developed in the “Kingdom of sola scriptura,” that is in the Protestant world: in Germany, England, the United States, etc. There is no Tradition or Church, or external authority that can officially interpret the Bible which speaks by and for itself directly to the heart of each Christian. At the Reformation, the doctrine of sola scriptura was seen as freedom for human interpretation. Sola scriptura was a protest against the heavy and oppressive authority of the Roman Church, as the Reformers saw it. The disadvantage of this position is that when modern science, archeology, and Biblical criticism began to examine the Bible and the history of Israel from the critical point of view, the advocates of sola scriptura often felt obliged to defend the Bible and a rather literal interpretation because the Scriptures were the only support for their faith. To accept that the Bible is not infallible or inerrant in everything seemed to open the flood gates to a relativity that, in the long run, would dissolve the very foundations of the Christian faith. From the point of view of both the attackers and the defenders of the Bible’s credibility, the last two centuries of the battle between science and religion seem to be a constant effort of reducing the Bible to the level of all human books and thus weaken the claim that it is the vehicle of God’s revelation to man. And the wars continue.

For sure, other Biblical exegetes, less fundamentalist but just as serious as the advocates of a literal reading of the Scriptures, have tried to maintain the integrity of the Bible while still taking into account scientific criticisms of all sorts. It is nonetheless true that many Christians—and Jews too—from every point of view feel that their faith is under siege from modern science and especially Biblical criticism. News headlines announce: ‘A new discovery in Israel.’ And some people think: ‘Oh, another one. What else in the Bible is not really true?’ Or, ‘Biblical scholars cast doubt on a traditional belief.’ And some ask, ‘okay, so what else is a myth?’

Protestant Christians are not the only ones touched by this question. Some Catholic Biblical scholars have adopted the methods of modern criticism to such a degree that it is difficult to distinguish their conclusions and the results of their studies from those of Protestants, even from some Jewish scholars. Catholics who study the Bible from this point of view are in fact very pleased that their Catholic faith has little or no influence on their studies. According to these scholars, their studies are scientific, objective and free of preconceived ideas imposed by a Church authority. The opinions of Catholic Biblical scholars, like those of people in any organization, are distributed over a wide range. Some researchers pay more attention than others to the directives of the Roman magisterium on Biblical studies, but for the most part, since Vatican II, Catholics and Protestants have been walking hand in hand, following the same methodology for Biblical studies. We can always ask how many “ordinary Catholics” would be surprised and shaken in their faith by the results of some Catholic Biblical scholars. Whether there are any fundamentalists in the Catholic Church, more or less hidden away, Catholic Biblical scholars have a great freedom, within certain limits, to pursue their studies.

As for Orthodox Christians, they are rather neophytes in the area, and many historical reasons can explain this. In general, they take much more conservative positions, as viewed by their Catholic and Protestant colleagues. It is not an exaggeration to say that a good number of Orthodox are very allergic to modern Biblical criticism. The conclusions of these studies, especially as seen by Russians and other ex-communist peoples, seem to be too close to communist anti-God propaganda, coming from the ferocious enemies of Christianity. Other Orthodox, very anti-Western in their outlook, want nothing to do with Biblical criticism. For them, it is just another example of the long slide of Catholics and Protestants into the abyss of unbelief. Still others are prudent but nonetheless open to the benefits of scientific study of the Bible; they are even eager to contribute.

The problem of the disparity between what the Old Testament texts say and the underlying historical event the texts describe is made more acute for Christians because Biblical scholars used the word mythos. In the New Testament, this word means “false, fantastic stories,” and it is always contrasted with alétheia, truth. The mythoi, whether Jewish, Gnostic, or pagan, are the opposite of the Gospel, and by extension of the Bible in general. The Bible is truth—understand, “real and historical events,” among other things—and myths are imaginary concoctions of the pagans. After all, the faith contained in the Bible is above all a faith anchored in history, in what God has really done for his people in history. To give the impression of cutting the link with history can only make believers quake in their boots. So it is not difficult to understand how Christian and Jewish believers felt, and still feel, the shock of the conclusions of scientific studies of the Bible which question the real and historical basis of many Scriptural events. Is the Bible myths or historical reality? Many Biblical scholars—of all confessions—see this antinomy as a false polarization and try in many ways to get out of the impasse, with more or less success. Western culture, however, is deeply influenced by Greek, Roman, Egyptian, and other mythologies—that is, fantastic stories about gods, goddesses, and heroes—but no one believes that Zeus and company are, or were, ever real. So, despite the efforts of Biblical scholars to give a positive meaning to mythos, speaking about myths in the Bible is always a risky endeavor and often requires as much time and energy to explain what that word does not mean as it does to explain what is does mean. And despite all the efforts of Biblical scholars, there is an unspoken, sometimes unconscious feeling, undertow, a lingering odor: whatever is myth is a fantastical story, not connected to history.

A suggestion that comes from afar

Everyone recognizes that the Orthodox are people of the icon: this religious image, bizarre for Western Christians, which is nonetheless so fascinating. Anyone who is interested in art in general and in Christian art in particular must study this form of religious painting, but some may legitimately ask what could possibly be the relation between the Orthodox icon and the scientific and critical study of the Bible. It is the purpose of this presentation to show that the notion (the theological vision, the conception) of the Orthodox icon can help Biblical studies get out of the sterile opposition between ‘myth or history.’ It is just possible that there is a third way.

II. What is an icon?

1. Icons are anchored in history.

First of all, an icon is obviously a visual, artistic representation—painting, mosaic, encaustic, etc.—of a person or a historical event. Every canonical icon—that is one that follows the rules and canons that govern its production, is anchored in history. The image of a human form supposes that under, behind, beyond, the work of art, there exists a real person: human, angelic, or divine. We have here the famous formula typos-prototypos, where the typos is the material object, the work of art, and the prototypos is the real person represented: a photo of my grandmother is the typos, and my grandmother herself is the prototypos. A picture of the Statue of Liberty, Marianne, John Bull, Uncle Sam, the statue of Sophia in Sofia, or four young girls called Summer, Fall, Winter, and Spring, the seasons, are not icons, even images, in the strict sense of Orthodox iconology because there are no real persons, hypostases—to use a technical term—behind the image. The same notion typos-prototypos is applied to an event because the icon of an event supposes the presence of persons in action. Where there is no historicity—for example, a mythological “event” or a fairy story—there is no prototypos, therefore no typos either, again according to Orthodox iconology.

2. Icons are a theological interpretation of a person or an event.

And yet, an icon is not a raw representation, photographic, direct, immediate, of a person or an event (supposing of course that such a representation is possible). Even a photograph shows a person from a certain point of view. In our world, everything is done, said, thought from a particular point of view. An icon is always an interpretation of the meaning of the person or event. The two levels, historical and theological, are combined in one visual representation.

- Let us take the icon of Christ Pantocrator. What Orthodox Christian, what person, seriously imagines that Jesus walked around Judea with a circle of light around his head and a cross inscribed in the light with three Greek letters ὁ ὤν; that he always, or even occasionally, wore a red tunic with a clavus on either or both shoulders, a clavus being a sign of nobility in Rome, along with a blue cloak; that he carried around in one hand a book or a scroll with a text from a book that did not yet exist at the time and in a language he did not speak or read. Anyone who thinks about it for a while understands that these elements of the icon of Christ are not historical; they are part of the theological interpretation of the person of Jesus that the Church throughout the centuries has added to the image of a bearded, Semitic man about 33 years old and which carries the name Jesus Christ abbreviated in Greek letters to IΣ XP, an image, however, that reproduces as much as is possible the physical and historical traits of this man. Let us not forget that the Church rejected the image of Christ as a child—sometimes a small man—or an adolescent in the Greco-Roman style: young, ‘beautiful,’ beardless, often naked. The Church did this precisely because such a representation did not correspond to history. But again, what Orthodox Christian would say that, because of these unhistorical characteristics, the image of Christ Pantocrator is a false image, and as such, should be eliminated? No one! The conclusion then: It is quite possible to have an image of a real and historical person which shows unhistorical elements that proclaim that person’s theological meaning, and that without being called a “false image.”

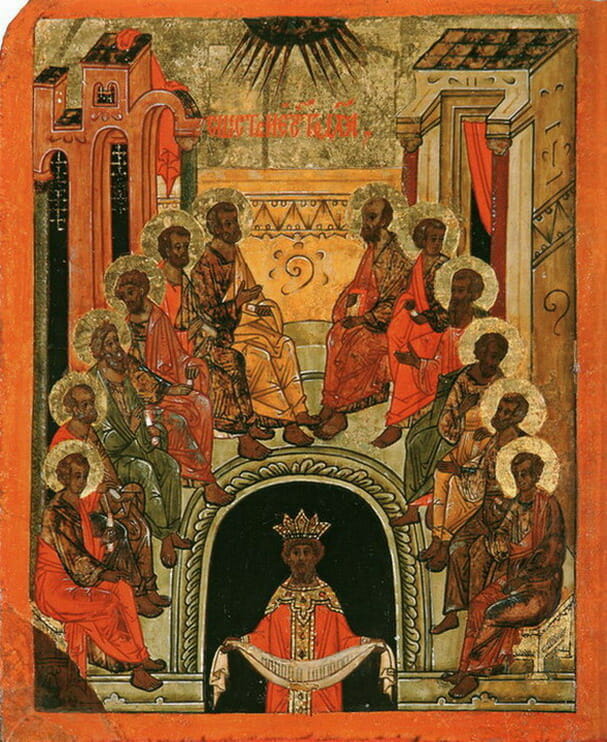

- And an icon of an event? Let us take the icon of Pentecost. According to the New Testament, (Acts 2: 1-13), after having received the Holy Spirit, the disciples were very agitated, speaking foreign languages, such that some of the people watching them make fun of them because of their frenetic behavior: “These people are crazy.” Others said they were drunk, at 9:00 a.m.! But what do we see on the Pentecost icon? First of all, not all the disciples are represented; only twelve of them are seated in a semi-circle, all very calm, relaxed, quietly talking to each other. At the top of the semi-circle, there is an empty space. On each side of this space, we see a man: on the right, St. Peter whom we can identify by his round face, his white, short, curly hair and beard. On the other side, we see St. Paul whom we can also identify by his classical traits: long face, long, pointed beard, somewhat bald. But why is St. Paul in the icon? At Pentecost, he was still Jewish and ferociously anti-Christian. And finally, at the bottom, we find a “man” wearing a crown. In fact, he is not a real man, but an anthropomorphic allegory of the universe, called Cosmos. Why he is there is another story. This typos, however, seems to be quite different from the prototypos event described in the New Testament. And in fact, in the Pentecost icon, the distance between the historical narration in Acts which describes the event, the prototypos, and the iconographic representation of this event, the typos, is very great, probably the greatest of all Orthodox icons. Nonetheless, no one says that the Pentecost icon is a false image.

- The Annunciation, March 25. Its icon is very close to the historical account in the New Testament: a conversation between two beings, one angelic and the other human. The icon, in its simplest form, only shows two human forms, in silent conversation. In fact, the simplicity increases its beauty. (See the Ustyug Annunciation, 1150-1200, The Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow). The distance between the type and the prototype hardly exists.

- We even have an icon which, as an event, has no historical prototype, even though the people represented were real, but the icon of the event is only a theological representation of an event that many have believed to be historical, but whose historicity is difficult to defend. I am speaking of the icon of the Entrance of the Mother of God into the Temple, November 21. It is not easy to imagine that a little Jewish girl really entered into the Temple in Jerusalem, going all the way into the Holy of Holy and lived there for some years. Nonetheless, the theological meaning of the “event” is very profound and has nourished the Church’s life for centuries.

So we have icons where the “space” that separates the artistic representation of the person or event, the typos, from the raw historical underpinnings, the prototypos, varies considerably: going from a non-biblical, and maybe non-historical event (the Entrance of the Mother of God into the Temple), through an image in which the type is very close to the prototype (the Annunciation), to another which shows some distance between the two (Christ Pantocrator), finally to an icon that shows a very great distance between the two (Pentecost).

And so now the question: Is it possible to apply the notion of an icon to Biblical texts—a notion which includes a variable distance between the type and the prototype and which allows for adding unhistorical elements to the image without “falsifying” the image?

Part 2 of this article will be posted soon.

The icon depicted of Christ Pantocrator depicted in the article does knot have a halo as described in the text of the article., though it does depict the other elements typical of such an icon. This may confuse some people (myself included) as to the “typical” representation of such an icon

Mr. Park,

The icon above does have a halo, but it isn’t very easy to see in the photo. The halo in this icon is burnished in the gold leaf, which when seen in person would make it clearly distinguishable.