Similar Posts

“What shall we offer Thee, O Christ, who for our sake was seen on earth as man? For everything created by Thee offers Thee thanks. The angels offer Thee their hymn; the heavens, the star; the Magi, their gifts; the shepherds, their wonder; the earth, the cave; the wilderness, the manger; while we offer Thee a Virgin Mother, O pre-eternal God, have mercy upon us…” [1]

The Theotokos of the Don Egg tempera panel icon with natural pigments (including ochres from the Forest of Dean in England and Lapis lazuli from Afghanistan) and 24 carat gold, 2011

The liturgical arts of the Holy Orthodox Church serve to point us towards and are a window upon the inexpressible beauty of God’s divine Kingdom, revealing to us the new Jerusalem and through its Holy Mysteries and iconography bringing us into communion with Christ, the Mother of God and the great saints of old and new. The experience of being within the sacred environment is a profound one, with all the liturgical arts working together in a sacred symphony which brings our being into the realm of the eternal and ineffable.

The timeless theological principles upon which the liturgical arts are based, the adherence to and comprehension of the sacred language of forms and colours, the materials used and the way in which this art is made are of immense significance. I hope to discuss some of these principles and methods in my contributions to the Orthodox Arts Journal throughout the course of the coming months, especially with reference to panel icons, manuscript illumination and the other arts of the book. This will include research into their symbolic and theological meanings as well as their history, materials and various technical aspects.

To begin with, I would like to explore the role of matter and the material world in the worship of the Orthodox Church. Central to our understanding of the material world is that matter is created by God, is good, and is part of the divine plan. This is expressed in Genesis 1:31, “Then God saw everything he had made, and indeed, it was very good.” In addition, we read that “Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, and cometh down from the Father of lights”. (James, 1:17)

The importance of the material expression of the sacred in Orthodox Christianity lies centrally in our understanding of the Incarnation, as St. Gregory of Nyssa says “…by means of the flesh which Christ has assumed, and thereby deified, everything kindred and related may be saved along with it.” [2] Furthermore, during the Transfiguration, grace passed from the divinity of the Lord to His human nature and then to His garments which shone brightly. Likewise in the Church, grace passes from Christ, and thence through the humanity which He shares with us and through us this grace can then pass to the whole material world. In Romans 8:21 we read “…the creation itself will be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God.”

Understanding materials in a deeper way is absolutely essential to retaining the integrity and beauty of the liturgical arts in the long term. One of the aims is to create work that reflects the incorruptibility and beauty of God and using poor or unsuitable materials undermines this symbolism. For example, selecting modern industrially produced paints may seem acceptable but when examined closely their characteristics often include inappropriate or poor quality elements and their pigments are often not light-fast or have been obtained through dubious or immoral chemical processes during which the resulting colour is a by-product rather than the intention of the process. How can this be compared to picking an individual stone, the flower of a subterranean cave and fruit of many thousands of years of natural growth? The radiant colours of ground malachite or azurite, for example, have no equal in the artificial palette and are completely light-fast, durable and glorious and therefore are both symbolically and functionally appropriate choices for the making of sacred art.

After the luminous blue stone Azurite has been ground and washed many times it is poured onto a plate to dry into a fine powder which is then used as a pigment in watercolour and with egg tempera.

The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament showeth His handiwork. (Psalm 19:1)

His All-Holiness the Ecumenical Patriarch Dimitrios said that “Unfortunately, in our days under the influence of an extreme rationalism and self-centredness, man has lost the sense of sacredness of creation…” [3]

Much of our understanding of the spiritual symbolism inherent in matter has been lost or subverted by the current secularist viewpoint, which has been shaped by various non-Orthodox ideologies and are often in contradiction to Orthodox theology. A desacralised society ceases to view creation as a bearer of the wisdom and love of God, regarding it instead is an accumulation of raw materials with an associated economic value. For example, in the case of gold, instead of seeing gold as something of divine source and a symbol of God’s divinity, love and incorruptibility, we are taught only to see its monetary value as opposed to the incandescent beauty of its substance, its inner essence or meaning.

Furthermore, our raw materials are now affected by the deleterious effects of industrial processes and pollution: “Growing industry is producing undisposable quantities of toxic wastes. The air, the waters and the skies, elements which were once pure, are today taking on a man made colour which affects their very essence.” [4] Animal products such as the egg, which is used in the making of egg tempera, may be the output of a battery farm with consequent abuse to the hen, compromising both its material quality and our role as carer for creation.

As a consequence of the above, it is now more important than ever that the liturgical artist and those who commission and use the liturgical arts understand and celebrate the true and exalted use of the material world. An understanding of the theology of materials and our relationship with them lies at the heart of the making process and is a route to the deeper comprehension of the sacredness of creation and contemplation of the reality of the Incarnation.

All material creation in its resplendent beauty is an icon; it is an image of higher things, a gift of love and generosity, and an embodiment of divine beauty. In the words of St. John Chrysostom “Nature is our best teacher. From the creation, learn to admire the Lord!” [5]

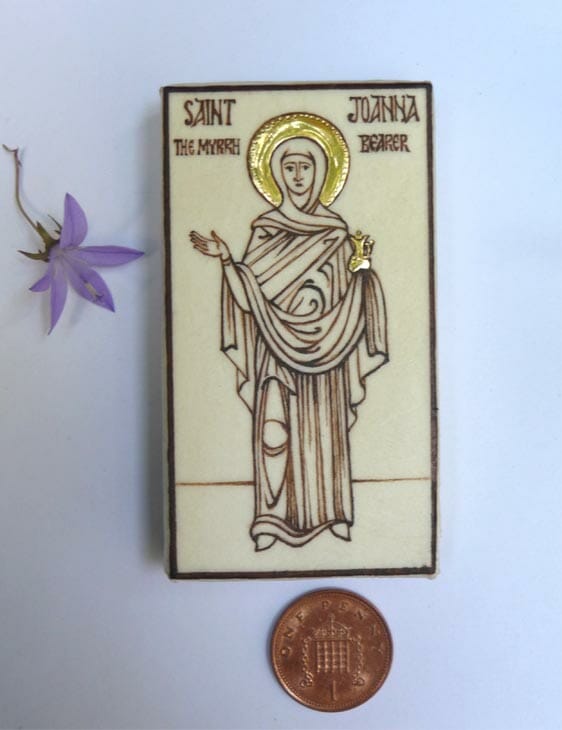

Miniature icon drawing of St. Joanna the Myrrhbearer in sepia ink on stretched vellum with 24 carat gold leaf (flower and 1 pence piece to indicate size).

The worship of the Orthodox Church is about the celebration and use of all aspects of the senses. This includes sight, sound, touch, taste and smell. It both uses and honours the materials, whether they are of wood, gold and paint, writing materials such as inks and quills, the holy bread and wine or through the burning of fragrant incense.

The purpose of the liturgical arts is the glorification of God and of thanksgiving. Mankind, being a partaker simultaneously of the material and the spiritual world, was created to refer back creation to God, in order that the world may be saved from decay and death. We were made to live eucharistically, with thanksgiving, for all that we have received. Therefore, it is not just a choice but our responsibility to make that gift of thanksgiving the finest it can be even if it does sometimes mean additional sacrifice and challenge. An icon will only last as long as the surface upon which it has been painted and the materials with which it has been made. It is meant to be a tactile liturgical object, not solely a painted surface, and therefore every aspect of it needs to be carefully considered during the making process. It must be robust enough to withstand the journey of adoration that will be its life whilst remaining a true and numinous symbol of the beauty of God.

The materials used to create liturgical art have not only their usual physical characteristics which can be measured by science but also profound meaning and symbolism which govern their placement and use in the sacred environment. This includes their practical and functional characteristics which are an essential consideration in their various applications. For example, in making an icon for exterior use, stone, metal or even ceramic would be suitable choices whereas textile or water gilded panel icons would not.

Working in harmony with creation rather than against it is of great importance. Traditional architecture and liturgical arts often employ regionally sourced building materials, thus harmonising with the surrounding environment. Natural materials are often used in their pure forms and certain materials which are exceptionally rare and precious, such as lapis lazuli, may be obtained from distant lands as a result of their special qualities.

A piece of the stone Lapis Lazuli fromCentral Asia, the pigment extracted from it is called Lazurite.

The contemplative use of natural materials in their pure forms also enables us in appreciating their essential qualities and goodness. I have often been struck when looking at many of the ancient illuminated manuscripts that many of the colours are used purely and this enhances our ability to love and appreciate each one for its distinct as well as its unifying qualities. Malachite, minium, indigo, orpiment and azurite are all easy to distinguish as are many others.

“For the greatness and beauty of created things the Creator is seen by analogy.” (The Wisdom of Solomon. 13:5)

The journey of making a piece of liturgical art begins a long time before starting to build or paint and this foundational work also includes building a personal relationship with materials at a much deeper level than simply going to a shop and purchasing items ready-made over the counter. For me as an artist, breakthroughs in technique have often occurred after preparing a new material painstakingly by hand and consequently, the experience of using it is then transformed into something which I could not have imagined. The finished artwork is always more beautiful and radiant than it would otherwise have been.

Hand made watercolour paints created using hand ground azurite (left) and malachite (right) which are kept in shells (in this case mussel shells).

Throughout the following few weeks in a series of chapters, I shall be exploring the foundation and meaning of creation, the role of the icon and the iconographer and various other aspects such as the significance of the Incarnation, the Transfiguration, the New Jerusalem and the giving of thanks.

It will be a great honour for me to share with you some of my research and experiences and I look forward to receiving your comments and thoughts with humble anticipation.

Illuminated miniature painting inspired by the decorative border of the Westminster Retable (c. 1290),Westminster Abbey, hand made watercolour paint with emeralds and rubies, 2011.

[1] Hymn for Royal Vespers, Christmas Day

[2] St. Gregory of Nyssa in “The Great Catechism” XXXV

[3] Speaking on Sept. 1st, 1989, The Day of the Protection of the Environment

[4] Orthodoxy and the Ecological Crisis, The Ecumenical Patriarchate assisted by the World Wide Fund for Nature International (WWF), pg. 7

[5] St. John Chrysostom, on the Statutes 12:7

I am looking forward to the rest of this series. You explain well the “why” behind the materials. I hope you will also be touching on the materials used in the fiber arts such as embroidery created for liturgical use.

I found this so interesting and moving. I already knew of the use of Lapis Lazuli for Mary’s dress, that natural pigments have subtle hues and of course that the reason we hold gold in such esteem is that it has unique properties. I had never before considered that there might be ethical reasons for choosing particular materials for liturgical decoration.

I too look forward to the rest of this series.

[…] I leave you with some examples of what she does and invite you to read her article: The Role of Matter in Iconography and the Liturgical Arts […]