Similar Posts

Over the centuries it had been noticeable that the iconography of Byzantine churches was consistent in content and style. It was most likely that the artists of religious images were following rules on what was to be painted, how images were to be arranged, and how they were to be rendered. In 1839, a painter’s guide to the arrangement of religious images, as well as style of painting, was discovered when the French art historian and archaeologist Adolphe Didron visited Mount Athos. The author of the guide was a Dionysios of Fourna who compiled the work from several other earlier anonymous writings. Little is known about Dionysios. He was born about 1670, went to Mount Athos as a youth, became a painter, was tonsured a monk, and died probably in 1746. He most probably compiled his work from various older sources between 1730 and 1734. It is accepted that the work was used as a reference book by painters on Mount Athos in the second half of the 18th-century as it contained all the information necessary to decorate a Byzantine church with religious images. His original text did not seem to have a title which was given one, Hermeneía tes Zographikés Téchnes (Explanation of the Art of Painting), by A. Papadopoulos-Kerameus when he published a Greek edition of the text in 1909 which is now regarded as the standard one. In the English translation of the French version of the text the title used was Byzantine Guide to Painting (1845) and in an English edition the Painter’s Manual of Dionysios of Fourna (1974) which is the title now commonly used.

Dionysios purpose in writing his work can be discerned from the first page of his manuscript in which he decries his unworthiness as a painter but not to fail in his endeavors he would like to offer other painters the “fruits of my laborious efforts …” in the form of a text. He writes: “… I have gathered together and composed [it] with the greatest care and skill … providing for the painters that are adorned with natural talents sources of the most beautiful art with the right order and use of colors and ways of finding subjects; how and in what parts of the sacred churches they must be painted with scenes, in order to decorate and paint with scenes properly fitting the imagined heaven of the church, …”

In the edition published by A. Papadopoulos-Kerameus in 1909 he made alterations to the original text such as creating chapter headings, and other sub-divisions, which are:

- Technical details including on the proportions of the human figure

- How to represent wonders of the Old Testament

- How to represent events according to the Gospel

- How to represent the Passion and events after

- How to represent the Parables (includes the Holy/Divine Liturgy)

- How to Represent the Feasts of the Mother of God (includes the 24 stanzas/stations)

- Sub-divisions include how to represent the twelve apostles, the four evangelists, the seventy apostles, the many holy bishops, the numerous martyrs and poets, and the miracles of the saints.

- How to represent martyrdoms according to the month of the year

- How churches and other buildings are to be decorated with scenes

In this final chapter on churches the text delineates how scenes are to be painted in churches with domes, in the narthex, in fountains (the phiale), in refectories, in cruciform churches, and in barrel vaulted churches. The chapter concludes with information on the tradition of painted images, the characteristics of the face and body of Christ and the Theotokos, and how to represent the blessing hand, names and epithets, and inscriptions. For domed churches the iconographic program begins with instructions on painting the image of the Pantocrator in the central dome, the four evangelists on the pendentives, the Theotokos Platytera in the center of the eastern vaults of the Holy Bema, and then the scenes and figures to be depicted in the five zones in which the interior of the church is divided for the purposes of painting.

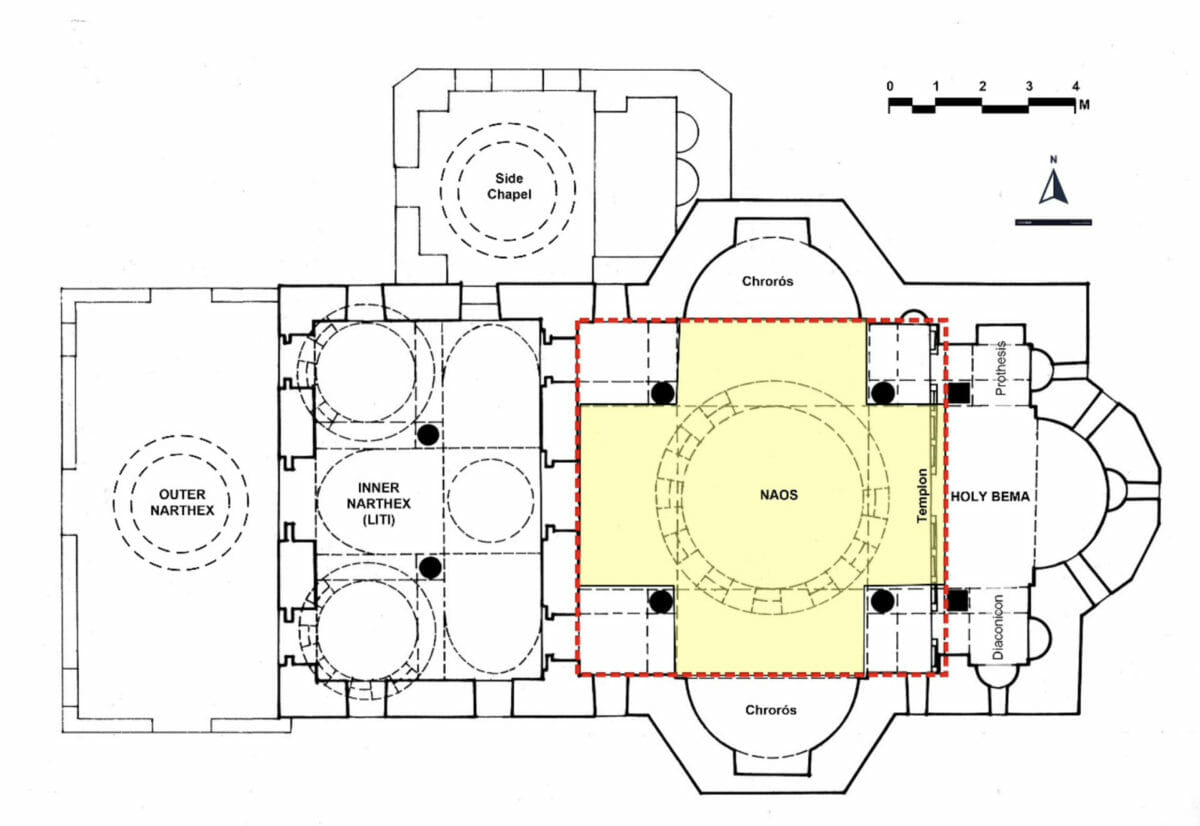

To illustrate the application of the Painter’s Manual any one of hundreds of Byzantine churches could be selected to do so. The one chosen here is the katholikón of the monastery of Gregoriou on Mount Athos as the author, Nikos Zias, who describes the wall paintings of the katholikón, cross-references them with the text in the Manual.1 Although this is a monastery church its core is the same as parish churches, a cross-in-square plan with a central dome, and the iconographic program is identical. The main difference is that the monastery church has two side apses, the choroí, and a second inner narthex. It is generally agreed that the Monastery of Gregoriou was founded in 1310 by St. Gregory the Younger. In 1500 the monastery was destroyed by pirates and set on fire then rebuilt in 1513 with the financial aid of Stefan, the ruler of Moldavia. An enormous fire in 1761 reduced most of the monastery buildings to ashes but it was rebuilt with funds from the metropolitan and the rulers of Moldavia and Wallachia. After another disastrous fire the present katholikón was completely rebuilt in 1768 in the centuries old Athonite style, a cross-in-square form with the addition of two side apses, the choroí, an inner narthex, the lití, and a Holy Sanctuary facing east. The katholikón is relatively small, the square of the cross-in-square of the katholikón interior measuring 7.75 m. (25.4 ft.). At the crossing point of the cross the column supported central dome rises 13.27m. (43.5 ft.) from the floor to the center of the dome, the drum of which is cylindrical on the inside and twelve-side on the outside. Between 1768 and 1779 Archimandrite Gavriil and the hieromonk Gregorios from the city of Kastoria painted the katholikón wall-paintings with Gavriil meeting the costs. It is significant that during the 17th and 18th centuries the city of Kastoria was one of the most important centers for producing painters of churches and icons who travelled and worked throughout Greece.

The central dome

According to the Painter’s Manual in the central dome there is to be a circular rainbow in the middle of which there is to be the image of Jesus Christ, with the title the Pantocrator, who is to be encircled by heavenly Cherubim and Thrones. Included in the image there is to be an inscription “See now that I, even I, am he, and there is no god besides me” (Deuteronomy 32:39). It should be noted that in practice the inscription has been incorporated in the form of the abbreviation O ΩΝ usually translated as “He Who Is.” On the outside of the rainbow, all round, are to be choirs of angels. In the middle of them on the east end is to be the Theotokos with her hands raised on either side and above her the inscription “Mother of God, Queen of the angels.” Opposite her on the west end is to be St. John the Forerunner. In a circle below the ring of angels are to be the prophets.

As prescribed by the Painter’s Manual the iconographers Gavriil and Gregorios divided the painting of the central dome of the katholikón of the monastery of Gregoriou into three concentric zones. In the inner circle, within a three-band rainbow, is the image of the Pantocrator in the customary bust form with the right hand raised in blessing and the left hand holding a richly bound book. There is the usual monogram for Jesus Christ, ICXC (I ησοῦ ς Χ ριστό ς with the medieval Greek C for ς), and the abbreviation O Ω Ν in a floral halo. In the second zone, in a narrow ring outside the rainbow around the circumference of the Pantocrator image, the iconographers painted the Cherubim and Thrones. They departed from tradition in painting this zone which, although it includes figures of angels, depicts the Holy Liturgy and Epitaphios instead of the Theotokos and St. John the Forerunner. In the third and outer zone, which is actually on the drum, an integral part of the dome, are the prophets. The iconographers divided the prophets, each holding a scroll, into two horizontal bands separated by a painted cornice, a shorter upper band with the figures of the prophets shown in bust form, and a lower longer band with the prophets depicted full-length. In his description of the prophets and the wording on their scrolls Zias indicates their derivation from the Manual which he terms as the “Treatise.” In the section of the drum pierced by windows individual full-length prophets of the lower band are placed in between windows, but in the northern section of the drum which does not have any windows the two bands of prophets are unified.

On the edge of the central dome depiction of the Holy Liturgy with the Holy Spirit on the Holy Table

On the curved surfaces of the pendentives, according to the Painter’s Manual, are to be painted the evangelists, one on each pendentive, and on the archivaults the Holy Mandelion/Veil, the Holy Keramion/Holy Cup, Christ holding a gospel with wording on the open page that he is the Vine, and Emmanuel holding a scroll with writing that he has been anointed by the Lord. The katholikón iconographers followed this direction by depicting the evangelists on the four pendentives with Matthew on the south-east, Mark on the south-west, Luke on the north-west, and John on the north-east. They painted the Holy Mandelion between John and Matthew (east archivolt), the Holy Keramion between Mark and Luke (west archivolt), Christ-Emmanuel between Luke and John (north archivolt), and Christ “I am the Vine” between Matthew and Mark (south archivolt). Following the Painter’s Manual descriptions Gavriil and Gregorios painted seventy individual apostles, each in a circular frame, on the intrados of the four arches.

Evangelist John (left pendentive), the Holy Mandelion (center archivolt), evangelist Matthew (right pendentive), & nine of the seventy apostles on the intrados

Evangelist Mark (left pendentive), the Holy Kerameion (center archivolt), evangelist Luke (right pendentive), & nine of the seventy apostles on the intrados

Evangelist Luke (left pendentive), Christ-Emmanuel (center archivolt), evangelist John (right pendentive), & nine of the seventy apostles on the intrados

Evangelist Matthew (left pendentive), Christ “I am the Vine” (center archivolt), evangelist Mark (right pendentive), & nine of the seventy apostles on the intrados

The Holy Bema

In the center of the semi-dome of the Holy Bema apse, architectonically the second most important feature in a Byzantine church, the Manual specifies the depiction of the Theotokos with the inscription “The Mother of God, Higher than the Heavens” (Platytera) and on each side of her the archangels Michael and Gabriel. Below the Platytera on the semi-circular apse wall of the Holy Bema is to be painted the Holy Liturgy, below that Christ distributing the Eucharist to the apostles, below that scene figures of bishops holding scrolls with Basil the Great and John Chrysostom in the middle, and in the bottom band holy deacons. In practice not all four bands below the Platytera are painted.

The vertical sequence laid out in the Manual of the scenes for the Holy Bema apse of Platytera, Holy Liturgy, Eucharist, bishops, and the deacons was not strictly followed in the Gregoriou katholikón apse as the scene of the Holy Liturgy is depicted in the second zone of the dome as noted above, which was a new trend in the 18th century. In the Gregoriou katholikón the sequence from the top to the bottom is then the Platytera, Eucharist, The Touching of Thomas and Christ Appearing in Galilee, and the bishops. There is no lower band with depiction of deacons and the wall surface is left undecorated. The architecture of the circular apse wall of the Holy Bema most probably prompted the choice and arrangement of the scenes. In the Gregoriou katholikón the upper section of the circular wall there is a row of three small windows whereas in many other churches the upper area is an unbroken surface for decoration. Thus, the scene of the Eucharist is disturbed by the intrusion of the three windows into the scene. In the zone below there are also three windows, but with a long central one, dividing the wall space into two providing for the two scenes The Touching of Thomas and Christ Appearing in Galilee to be painted on either side of the central window.

Second zone in the Holy Bema: The Holy Eucharist (center detail) with Christ at the Holy Table (center) and the apostles Peter (left) & John (right)

The Theotokos Platytera in the Gregoriou katholikón is represented seated on a decorated throne, dressed in a blue robe and golden cloak, with Christ in her lap, the archangels on her left and right, and the traditional inscriptions ΜΡ and ΘΥ, the first and last letter of each word in Greek of Μ ήτη ρ (τοῦ) Θ εο ῦ. Beneath the Platytera image, the second zone, is the upper area of the semi-circular wall of the apse where instead of the Holy Liturgy is depicted the apostles accepting the sacrament of the Holy Eucharist, reflecting the rites performed in the Holy Bema. The scene, with Christ in the center, is intruded upon by three small actual arched windows unrelated to the setting. Christ is shown holding the bread in his right hand for the apostle Peter and in left hand the cup for the apostle John. He stands behind a table (the central small window infringes the painting of the table), on which is a salver with broken bread and an open gospel book. In the background behind Christ is a portico with fluted columns and on either side other buildings and the inscription which reads “The Imparting of the Lord of His Body and Blood to the Apostles.” Zias notes that the “depiction corresponds fully with the description in the Treatise.”

In the third zone on either side of the long window are two scenes, “The Touching of Thomas” (on the left) and “Christ Appearing in Galilee” (on the right). It is not known why the iconographers selected these two scenes. In the scene “Touching of Thomas” the apostle is shown on right side of Christ and Peter on his left side with the remaining apostles grouped behind. In the background is an interesting building which appears to be a polygonal hall with an open arcade with a framed entrance. In the outdoor scene of “Christ appearing to the Apostles in the mountain in Galilee” he is shown elevated and blessing with both his hands. Below the two scenes is the fourth zone which according to the Manual is to be depicted the bishops of the church. Six are shown full-figure each holding a scroll. They are Sts. Nicholas, Athanasios, and James the Just as a group of the three on the north side of the long window, and the fathers of the church Basil the Great, John Chrysostom, and Gregory the Theologian as a group of three on the south side. Zias records that the depictions follow those laid down by the Treatise/Manual as does the wording on the scrolls.

In Byzantine churches separating the Holy Bema from the space of the naos is the templon (iconostasis), a screen decorated with icons. The Painter’s Manual does not refer to the whole arrangement of icons on the templon which follow a traditional iconographic program of its own which will not be discussed here. Dionysios only refers to the inscriptions for the Feasts that will adorn the templon and lists fifteen Feasts rather than the traditional twelve, noting that the Crucifixion is always to be the center icon.

The prothesis and diaconicon

The Manual’s description of the scenes to be painted inside and outside the prothesis and diaconicon on their vaults, cupolas, groin-vaults, wall spaces, the space above the columns and on column capitals is not written in an entirely clear manner. The terminology in the text is confusing and thus difficult to assign particular scenes and figures to architectural features. What appears to be postulated is that the cupola of the prothesis is to show Christ in bishop’s robes sitting on a cloud, encircled by Cherubim and Thrones, blessing with one hand and in the other holding an open Gospel with the words: “I am the good shepherd” (John 10:11). Above him is to be the inscription: “Jesus Christ the high priest.” In the drum below the iconographer is to depict bishops of his choice and on the semi-circular apse dome is to be shown the Deposition from the Cross. On the diaconicon cupola is to be painted the Theotokos with the Christ Child holding her hands outstretched with an inscription surrounding her: “The Mother of God with the wide wings of the Heavens.” As in the prothesis on the diaconicon drum a selection of bishops is to be depicted. The Painter’s Manual does not appear to prescribe an image for the diaconicon semi-dome but only that below are to be depicted the scenes of Moses and the burning bush, the three children in the furnace, Daniel in the lion’s den, and the hospitality of Abraham. The remaining stipulations of the Manual for the prothesis and diaconicon are particularly confusing.

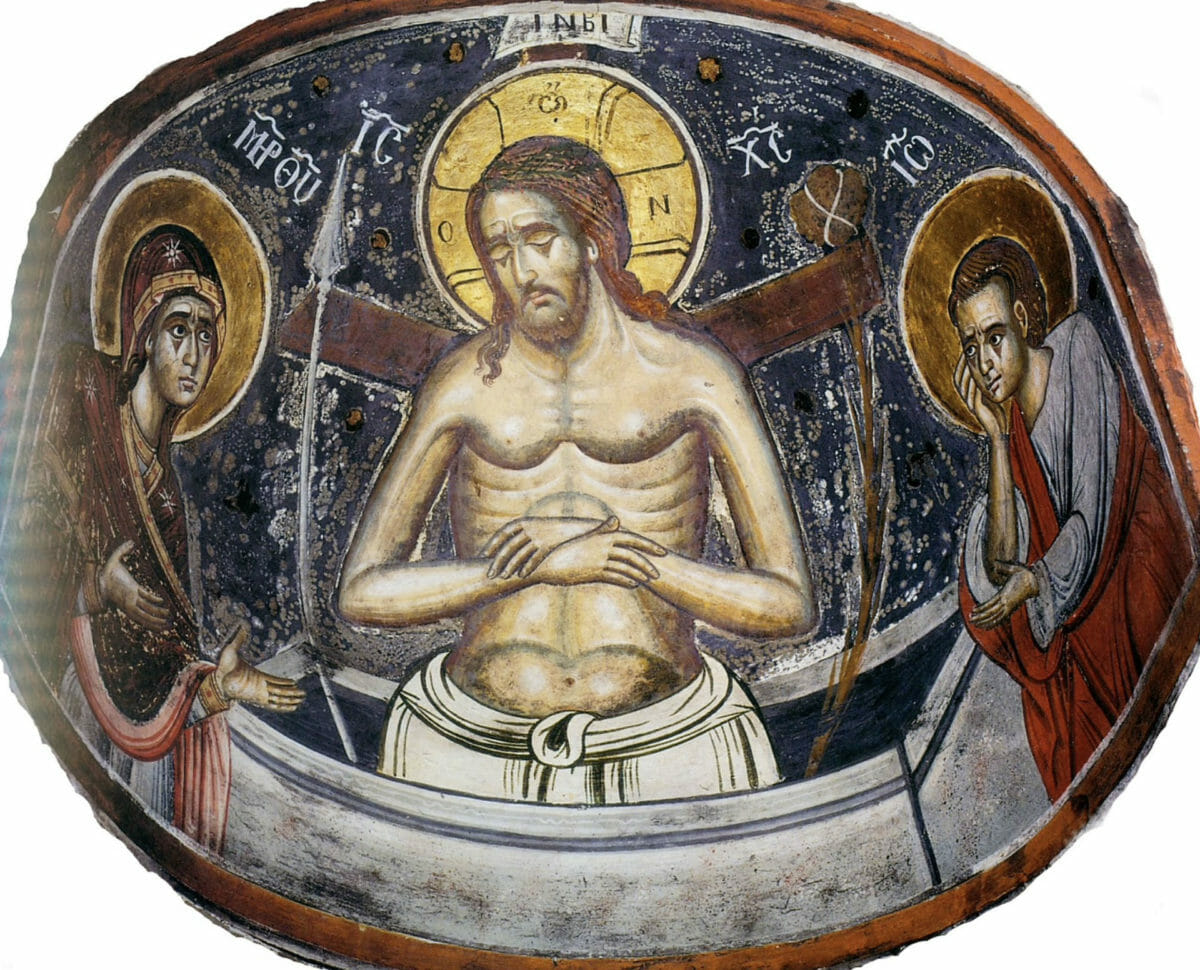

In the Gregoriou katholikón the prothesis and diaconicon are on the small side, they do not have cupolas or apses but are rather just niches, and thus have restricted surfaces available for decoration. On the conch of the prothesis is painted the Humiliation of Christ and below, on either side of the windows are depicted Sts. Dionysios and Hierotheos. As the Painter’s Manual does not appear to identify the scene to be painted in the diaconicon apse semi-dome the iconographers have painted on the conch the scene of Christ on a high throne as king with an open book with the words: “Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?” (Isaiah 6:8). Below on either side of the window are depicted Sts. Anthimos and Germanos.

The narthex

According to the Painter’s Manual of Dionysios of Fourna in the narthex if there are two cupolas in the one is to be painted Christ and a choir of angels and around them a choir of saints. In the other cupola is to be the Theotokos with the Christ Child held by angels and around them a circle of prophets. In the pendentives are to be eight named poets, seated and writing. Over the Royal Door leading into the naos is to be an enthroned Christ holding a Gospel with the words: “I am the door: by me if any man enter in, he shall be saved” (John 10:9) and on either side of him the Theotokos and St. John the Forerunner. On the opposite, west, wall contains the entrance door to the narthex, is to be represented the seven Ecumenical Councils. On the upper area of the remaining wall space is to be painted scenes from the Old Testament and on the lower level the iconographer’s choice of saints and poets.

The narthex of the Gregoriou katholikón is a later addition, dating from 1840, but as the paintings from that time do not remain today unfortunately a cross-reference cannot be made with the Manual. In the lití, which is a feature of monastic churches, the decoration in the Gregoriou katholikón consists of scenes from the second coming of Christ, the ecumenical synods, and various other events.

The walls of the naos

With reference to the walls of the naos the Painter’s Manual indicates that in the first of the five zones are to be painted the twelve principal feasts (the Dodecaorton): the Annunciation, Nativity, Presentation, Baptism of Christ, Transfiguration, Raising of Lazarus, Entry into Jerusalem, Crucifixion, Anastasis, Ascension, Pentecost, and Dormition of the Theotokos. In the second zone below are to be represented the works and miracles of Christ. Underneath in the third zone the iconographer is to paint a selection of parables. Specifically, in the third zone of the west wall, above the central entrance door from the narthex, is to be represented the Dormition of the Theotokos. Below in the fourth zone are to be represented half-length figures of saints in medallions and in the fifth zone underneath are to be painted the martyrs of the Church.

In the Gregoriou katholikón the wall-paintings of the naos are arranged in three zones, not five, separated by two cornices with the depictions of scenes and portraits, which Zias points out, are according to the Treatise/Manual. In the first and highest zone is represented the Twelve Great Feasts of the church year as well as scenes from the life of the Theotokos, from the life of St. John the Forerunner as well as of individual saints and prophets. In the second zone there are illustrations from the Akathistos Hymn which is not commonly illustrated in churches during the period of the Byzantine empire but was favored on Mount Athos in the 18th century. It is a theological work with an exceptional poetic quality. The Hymn consists of twenty-four stanzas (oikoi) which are superbly represented visually in painted panels. Zias notes the scenes that are depicted follow individual descriptions in the Treatise/Manual. In the third zone around the walls of the katholikón are painted the saints, with a predominance of Warrior Saints, depicted almost life-size with splendid dress and bossed haloes. As it is a monastic church the figures also include portraits of great individuals from the world of monasticism.

Second zone of the naos walls: The Akathistos Hymn – “Aggelos Protostatis” (An angel of the First Rank)

Three examples of images from the three zones are first, the Nativity as one of the twelve principal feasts. Guided by the Painter’s Manual, the iconographers of the Gregoriou katholikón painted the Nativity in two parts. In the upper part there is a choir of angels in the clouds of a starry sky with a broad ray from a star coming down on the head of the infant Jesus. He is wrapped in swaddling clothes in a crib inside a cave (Byzantine tradition) with a kneeling Joseph on the left and a kneeling Theotokos on the right. On the upper right of the lower section an angel shows a shepherd boy the place of the Nativity and lower down a shepherd boy plays the flute, while in the other direction the three Magi are seen approaching on horseback. In the second zone each stanza (oikos) of the Akathistos Hymn begins with successive letters of the Greek alphabet. In the example the scene is from the first stanza with the letter A (Aggelos Protostasis). Panagia, seated on a stool holding a book with unknown text, receives the salutation of the angel who is depicted with bright garments windswept behind him. The third zone of the naos walls is decorated mainly with Warrior Saints portrayed in military dress and holding weapons. In the example three named Warrior Saints are depicted. In the third zone other saints are also included such as the elderly doctors of the desert, Sts. Anthony, Arsenios, Hilarion, and Theodosios the Cenobite.

Third zone of the naos walls: The Warrior Saints – Theodore Stratilates, Theodore the Recruit, and Christoforos

Style

The focus here has been on the arrangement of images in relation to the architecture of Byzantine churches. But a word has to be said about their painting style. As the iconography was undertaken in the 18th century it is not surprising to find western influence in the paintings such as symmetrical positioning and an articulated architecture, some with classical features. Perhaps the most notable influence is on the natural landscapes which are not painted with angular mountains but with low, gently rounded hills. Human figures still convey a spiritually in their lightness, in their slender and insubstantial bodies despite the more natural faces. Colors are bold but limited to red, blue, gold, and white. But among the trends in Orthodox ecclesiastical painting in the 18th century was a drive to return to the traditional style as exemplified in the work of Manuel Panselinos. Principal exponent of the movement was Dionysios of Fourna whose handbook codified the technique of the past from his study of paintings on Mount Athos and from earlier manuscript treatises. Although the katholikón of the Gregoriou monastery was painted nearly a half a century after the compilation of Dionysios, it cannot be said for certain that the iconographers consciously followed the Painter’s Manual. The iconographic program and painting of figures and scenes, however, adhere very closely to the descriptions in the Manual.

Conclusion

From the description of the iconography of the Byzantine church of the Monastery of Saint Gregorios it is clear that a distinguishing characteristic of Byzantine churches is the integration of the iconography with the architecture of the church. Instances illustrated are the integration are the Christ Pantocrator in the central dome, the Theotokos Platytera in the semi-dome of the sanctuary apse, and the ordered icons of the templon (iconostasis or icon-screen) that divides the sacred clerical space of the sanctuary from the laity space of the naos (nave). These three features are standard in Byzantine churches, predominantly domed ones, built from about the 10th century until today in Eastern Orthodox communities around the world. Many have, in addition, arranged frescos on the walls of the naos and narthex.

The images are not merely art objects but are a sacred representation meant to transport the faithful to the spiritual realm. Specifically, the images are reminders of another reality beyond the physical world. During the 10th and 11th centuries the interior of the Byzantine church came to be conceived as an image of the cosmos and a coherent scheme developed for the decoration of its spaces. The images were arranged according to a scheme that began with the entrance to the church, the narthex, continued into the naos and culminated in the Holy Bema. Arrangement of images in the interior of the church were codified, a tradition was developed and maintained until the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. In the following centuries the tradition of an organized arrangement of images in Eastern Orthodox Byzantine style churches everywhere was maintained even to the present day.

1Nikos Zias, “The Wall-Paintings” in Nikos Zias and Sotiris Kadas. The Holy Monastery of Saint Gregorios: The Wall-Paintings in the Katholikon. Mount Athos: Holy Monastery of Saint Gregorios, 1998, 45-83. He is also the author of a book on Photis Kontoglou, a 20th century iconographer who championed the traditional approach. The illustrations in this article are from the book by Zias and Kadas and is gratefully acknowledged, and used in accordance with the code for the analytical writing use of copyrighted material.

If you enjoyed this article, please use the PayPal button below to donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

Wow!! Wonderful article! I had the pleasure of re-publishing the English edition of the Painter’s Manual back in the 1970’s when I was publishing books on Iconography as Oakwood Publications. I finally sold all my publications including the Iconographer’s Pattern Book (the Stroganov style). The Painters Manual is probably still available through St. Vladimir Seminary Bookstore. Best, Philip Tamoush

Hello Philip

Thank you very much for your comment

Best

Nicholas

Hello Nicho,

Any chance you can give me a link to where I can purchase the Greek language version of the book? I would like to give it to someone who does not speak English well.

Thank you,

Mark

Hello Mark

A good link is

https://www.google.com/books/edition/NOCTES_PETROPOLITANAE/5mVSMBsCfy4C?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=dionysios+of+fourna&printsec=frontcover

Best

Nikos