Similar Posts

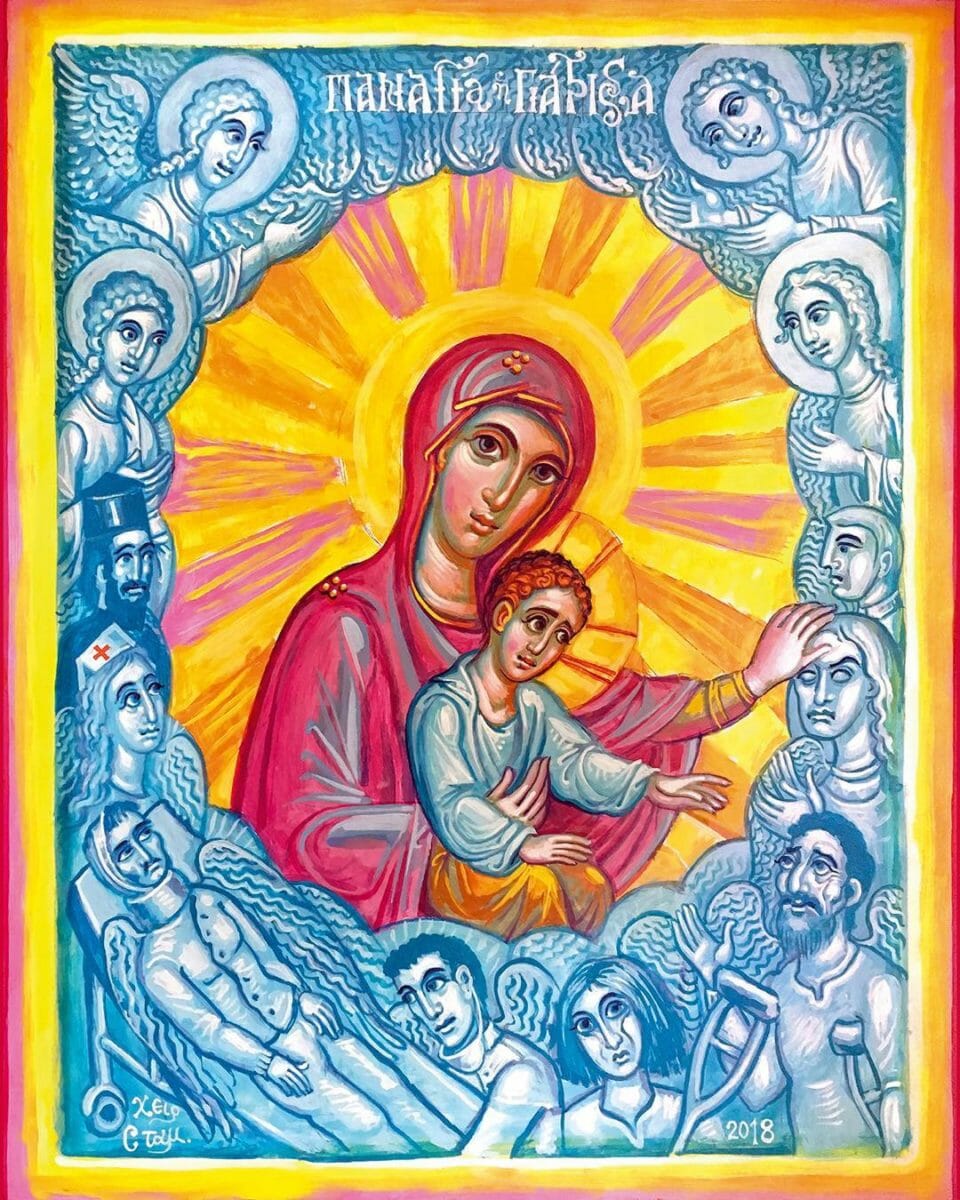

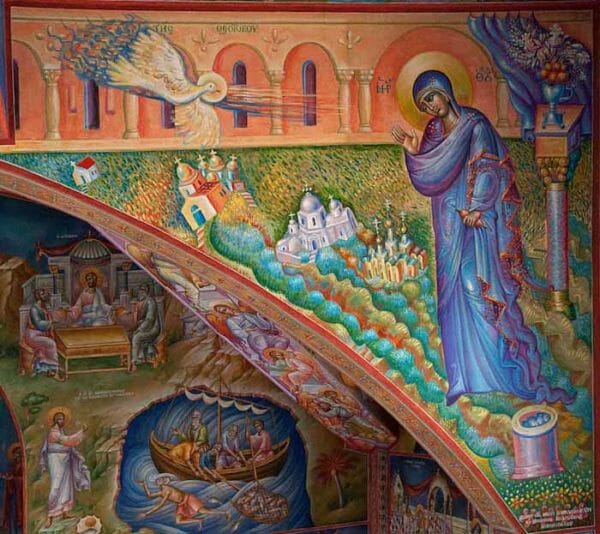

Panagia the Healer, by Stamatis Skliris. Acrylic on canvas, 2018. Icon made for Asclepion Hospital in Voula, Greece.

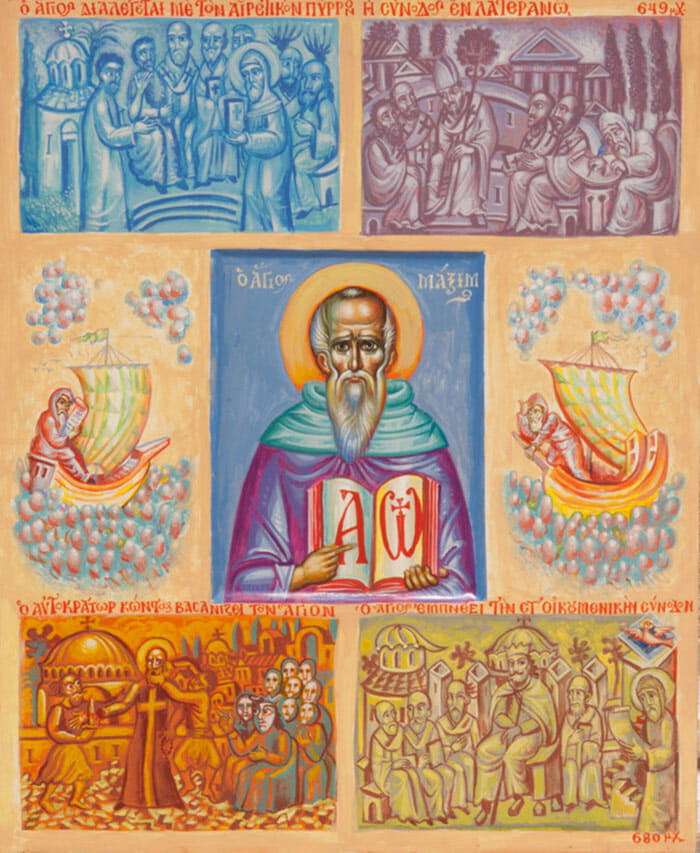

It could be said that Fr. Stamatis Skliris ranks as one of the most important, albeit idiosyncratic and challenging, contemporary iconographers residing in Greece today: idiosyncratic, because his style stands out in a category of its own, in its personal, expressive potency and unique, at times odd, pictorial synthesis; challenging, because he often breaks all norms or expectations of what a traditional icon is “supposed” to look like. He doesn’t seem to fit any stereotypical standards. Thus at times he leaves the viewer feeling uneasy. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that to some his work and ideas rank as “controversial”, in their daring and unconventional approach, especially since his style consists of a fertile synthesis of the icon painting tradition with modern visual trends. Hence, though I’ve been hesitating for a while, I have finally decided to go ahead and discuss his work, since to do otherwise would be a major oversight on our part. He is simply a major contributor to the revival of icon painting, in both the realm of theory[i] and practice, and cannot be readily dismissed or ignored as insignificant.

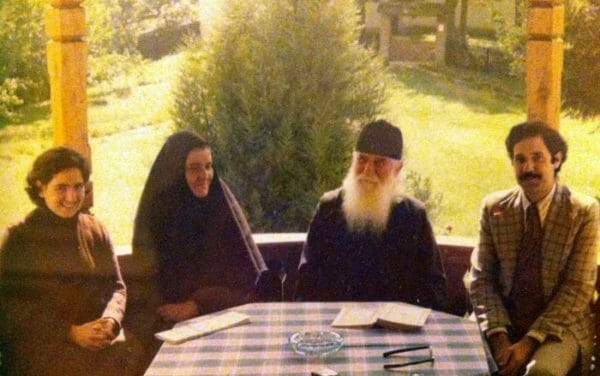

Fr. Stamatis Skliris was born in Piraeus in 1946. Initially he graduated from Medical School (1971) and then studied Theology at the University of Athens (1976). He continued his studies in Belgrade at the Theological and Philosophical Faculty, attending lectures in Theology and Art History. He also attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Paris (Ecole des Beaux Arts). While residing in Serbia he spent time mostly in Ćelije Monastery, in the immediate vicinity of St. Justin (Popovic). He would go on to be ordained to the priesthood and since 1979 has been serving in Athens.

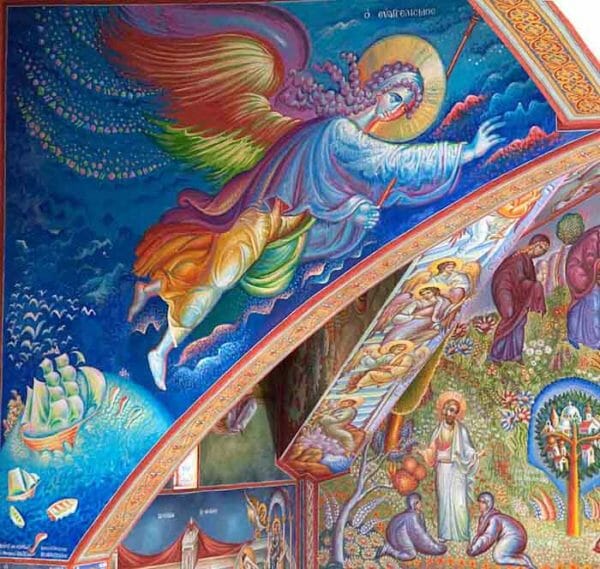

Through his extensive studies of Serbian monuments and frescoes Fr. Stamatis has developed a unique interpretation of Byzantine art, clearly evident in the many churches he’s painted. During his stay at Ćelije Monastery, he decorated the monastery chapel devoted to St. Stefan Dečanski. He has also painted the Church of St. Elias the Prophet in Piraeus, of St. George in Stamnica, and the chapel of the De Pahlen-Agnelli in Geneva. Furthermore, he completed the icons in the church dedicated to St. Nektarios in Voula, the church of Evangelistria in Halandri, Greece and the church of St. Maximos the Confessor in Kostolac, Serbia, among others.

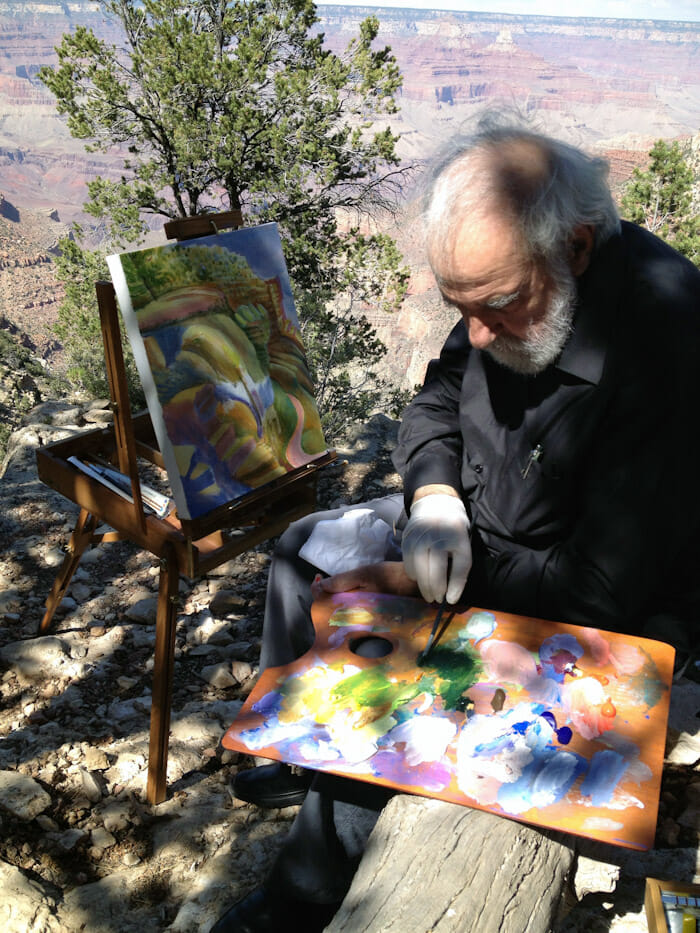

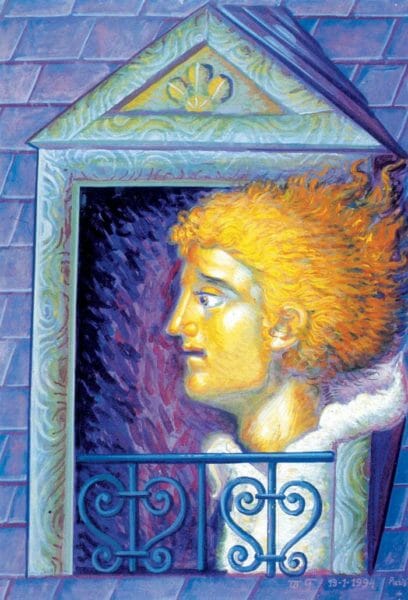

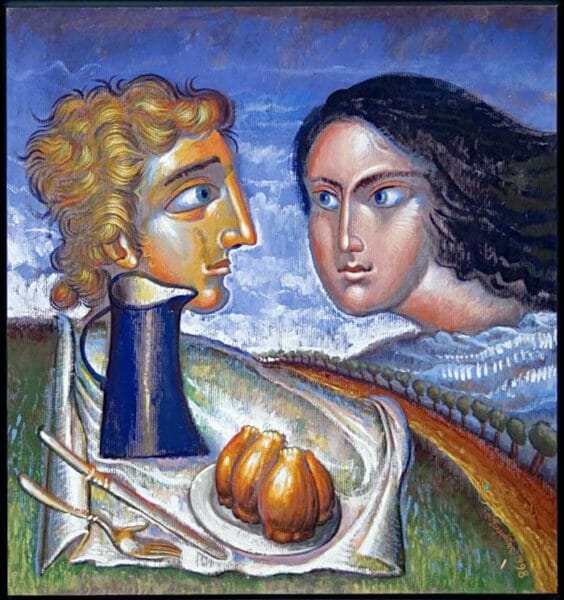

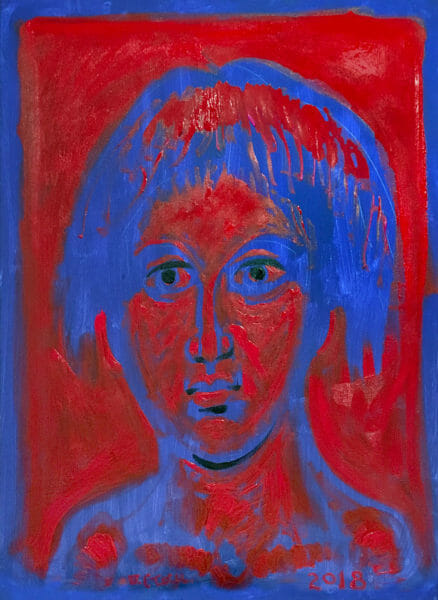

Fr. Stamatis’ work embraces not only monumental and panel icon painting, but also book illustration and non-liturgical painting. The cross-fertilization between the idioms is evident. His non-liturgical work is of particular interest, for in it we see his incessant experimentation with the figure, imaginative portraiture, still life and landscape painting. These works at time verge on the surrealistic and include mythological themes. They’re generally executed in an expressive manner, rough at times, and tend to have existential connotations. Whether it be icons or non-liturgical painting, the unique – somewhat eccentric – personality of Fr. Stamatis always comes through.

Fr. Stamatis’ icons leaves you wondering, scratching your head, thinking, “Is this allowed? Is this appropriate in a liturgical context? Has he gone too far?” He shakes the viewer out of complacency, inviting him to engage with the image actively— whether you “like” it or not — confronting him with solutions which shatter conventional expectations. He seems to tell us: “Take it or leave it.”

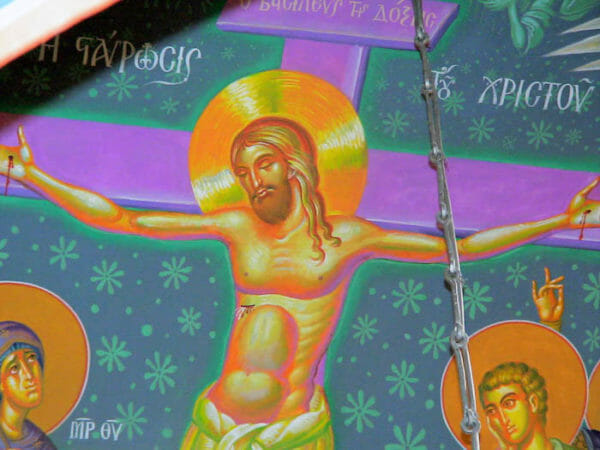

At times you are willing to accept the results. Other times it indeed goes too far, verging on kitsch and an “outsider art” sensibility. Some moments can be said to be too emotionally charged, if not melodramatic. Then there are instances when the color gets garish and the formal extravagances too noisy. Nevertheless, the image is always forceful, pulsating with life, if not exhilarating: buoyant at times, resplendent at others. There is a child-like naïveté in the work of Fr. Stamatis that is hard to gainsay and completely reject. There is a valor is his willingness to open his inner world for all to see. These qualities imbue his work with a stamp of true authenticity.

Be that as it may, in spite of the various oddities and stylistic incongruences— he is by no means a graceful classicist — he nevertheless exhibits a masterful command of painting. His brush handling is loose, with a lot of texture and gestural range: it can be virtuosic, although a bit wild at times. He is undoubtedly a great colorist. His color is particularly powerful, rich, both festal and electric, indebted to Impressionism, Fauvism, Pointillism and the Expressionism of Vincent van Gogh. Then there is his creative imagination that can leave the viewer awed with his genius, even if he does not particularly care for most of the results of his daring experiments.

In short, Fr. Stamatis is a force to contend with. Whether or not one feels his approach is the best direction to take, nevertheless, his work unapologetically presents us with one possibility in tackling the pictorial challenges and questions facing contemporary iconography today in light of modernity. And that is the kernel of the matter, for Fr. Stamatis does not shun modern art, but rather incorporates whatever it offers as salvageable and compatible within the principles of the icon painting tradition. In fact, looking back to the development of the ecclesiastical painting in Byzantium, he considers the Christian transformation of the standards of Greco-Roman painting as a kind of “modernism” prior to the Modernism which emerged in the late 19th century. He argues:

We could even say that the first modernism in world history was founded not in the 19th century by Western art movements, but in Byzantium. If the essence of modernism lies in the liberation from classical conceptions of painting and the deliberate change of the canons and introduction of new ones, then that happened for the first time in Byzantium, when a change occurred in relation to the Classical, Hellenistic, and Greco-Roman artistic tradition… As for the possible influence of Modernism on Orthodox icon painting, I personally cannot conceive a living Christian painter of the 21st century who would live in such a way as to ignore and disregard the great achievements of Western art history, like Impressionism, for example, and who would be able to live isolated from the problems that surround modern man.[ii]

St. Knez Lazar & St. Despot Stefan Lazarevic, with symbolic depiction of Non-Liturgical Life at bottom, south apse, St. Maximos the Confessor in Novi Kostolac. By Fr. Stamatis Skliris.

Thus Fr. Stamatis’ stance is in dialogue with, rather than antagonistic to, the formal developments of modern painting. But he engages in this stylistic conversation in a way that veers away from the cliché geometric reductionism usually associated with an exploration of modern idioms, preferring to deal with a more robust and pronounced handling of volumes. On the relation between the Byzantine icon tradition and contemporaneity he states:

From a particular moment onwards, our traditional art had touched upon my heart. I thought I had discovered a kind of a hidden, mystical beauty. I bathed in the light of the Byzantine icon regarding everything else as being secondary. However, I needed to find a way—after having lived out tradition internally—to express it in my own work in relation to the issues of our time. That is: I needed to act just as an ancient Hellene or a Byzantine would act if living in our times. I borrowed the bright colors and brilliant brush strokes from Impressionism and clothed them with the centripetal lighting of an icon. It is thus, in my opinion, that emerged an art of painting similar to the Hellenistic, Greco-Roman, but, simultaneously, both Byzantine and modern. In other words, the East has moved closer to the West, and the so-called secular art to that which is seen as sacred.[iii]

This approach to the pictorial problems of icon painting is therefore one which shuns formulaic repeatability and predictability, leading to monotony and an unengaging viewing experience. Fr. Stamatis’ clarion call is authenticity. He invites other iconographers to dare to discover their own unique voices within the tradition, in “reaction to the great achievements of Western art history,” and thereby go beyond the replication of older icons. Otherwise, he feels the result will be a kind of iconography that is “anachronistic and symptomatic of a ‘false Orthodoxy.’”[iv]

Crucifixion, St George the Great-Martyr Church in Stemnica, Greece, Wall-Painting by Stamatis Skliris, 2004. By Fr. Stamatis Skliris.

But the road toward authenticity, as he suggests, is not so simple: it should unfold “after having lived out tradition internally,” within the Eucharistic life of the Church. Hence, Fr. Stamatis states that “authenticity is foremost a spiritual problem, and only secondarily a painterly problem.”[v] He adds, “First, when authenticity in the way in which the Holy Eucharist, Christ, and love for fellow man are lived and experienced is lost, this is then reflected in ecclesiastical painting through the phenomenon of replication. We should accept and acknowledge the fact that there are, for example, many Christians who copy, in the spiritual life, the demeanor of their spiritual father outwardly, as if spiritual life is a matter of demeanor and not inner experience.”[vi] So let us take brief look at how this spiritual problem relates to the ecclesial sphere.

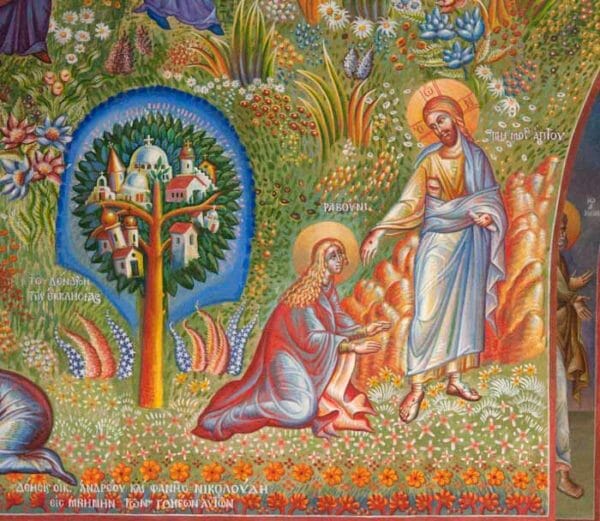

The Lord appearing to St. Mary Magdalene after the Resurrection, St. Nektarios in Voula, by Fr. Stamatis Skliris.

Holy Myrrhbearers Encountering the Angel at the Empty Tomb, St. Nektarios in Voula. By Fr. Stamatis Skliris.

The inner spiritual experience and gifts of each member of the Church are unique and inimitable. Thus the saints actualized their deification in unique and inimitable ways that distinguish them one from the other, not only in their temporal but also eschatological existence. Therefore, as Fr. Stamatis notes:

Although much of the emphasis focuses upon the Last Times, a necessary feature of the person in the icon is their particular way of life and the relationships in their lives within historical time. This is why the icon reflects the eschatological relationship and the salvation resulting from this in the form of certain specific events which stamped the existence of the persons depicted while they lived in historical time and which lent their mortal existence certain characteristics which remain into eternity.[vii]

But the uniqueness of events which characterizes the life of the saints and sacred history continue to ripple in the life of the Church every time an icon is painted, with soteriological and eschatological implications:

By having the icon painted and by reverencing it, the Church creates another event. The wood or wall on which the icon is painted, were formerly neutral in Christological, soteriological and eschatological terms, but now assume the dimensions of a new and unique event, because through them, in a special manner, the Church is linked to the eschatological existence and personality of the saint. In this way we understand what the Fathers wrote in texts and in hymns and what was expressed as a Term [Definition] at the 7th Ecumenical Synod: that through the icon of Christ and those of the saints, creation is sanctified.[viii]

Adam Naming the Animimals in Paradise, St. Maximos the Confessor in Novi Kostolac, 2006-2010. By Fr. Stamatis Skliris.

All of this rippling of unique events, according to Fr. Stamatis, has implications for the iconographer’s creative act. In other words, the icon should in turn – if it is to be a genuine expression of ecclesial life – reflect the same uniqueness and inimitability as an event of personal creativity. Hence, the act of icon painting must unfold from a living and unique inner experience of communion in Christ, specifically one between the painter and the saints. This authentic creative act, in turn, facilitates a living and genuine communion between the temporal ecclesial community and its eschatological members. The painter as an Evangelist[ix] keeps the memory of the saints alive, the unique and inimitable ways in which they’ve actualized their deification. But as Fr. Stamatis explains:

This ‘memory’ isn’t simply a sentimental reminder, but participation in the Eucharistic community, in the ‘eternal memory’, that is in the memory of our eternal God and Father, which maintains the saint – and, by extension, every believer – in eternal existence and communion. The Eucharistic community, with its feasts which require their relevant iconography, causes the painter to create an event, the new icon of the saint, through which the community returns once more into a relationship with the eschatological person, the saint.[x]

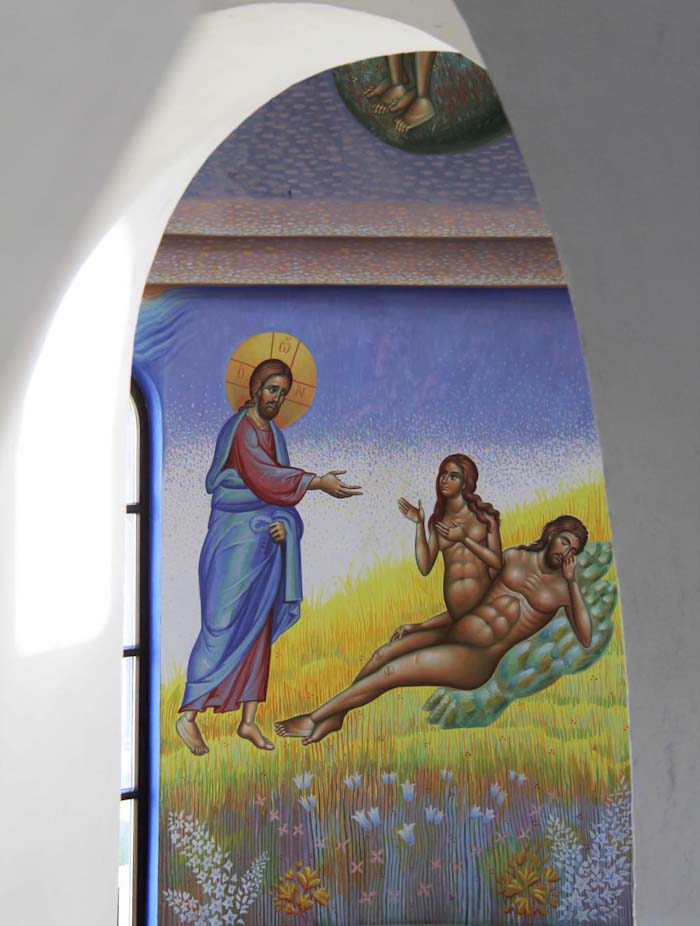

Creation of Adam and Eve, St. Maximos the Confessor in Novi Kostolac, by Fr. Stamatis Skliris.

Thus, according to Fr. Stamatis, iconizing unique persons and events requires unique, inimitable, authentic creative acts which reflect, as a living and continuing reality, the communion which exists between the historical and eschatological dimensions of the Church. Otherwise our experience of communion within the ecclesial community suffers in its lack of authenticity. Therefore, he observes that “an iconographer didn’t simply refrain from copying an older icon, but didn’t even copy the ideas of one of his own, if he was painting the same subject for the second, third or umpteenth time. Because clearly he would have believed that every new icon was a new and unique event of communion between the Church and the saint depicted.”[xi]

We can then begin to see how the question of authenticity is “foremost a spiritual problem and only secondarily a painterly problem.” We might not ascribe to all aspects of Fr. Stamatis’ assessment, but it’s worth pondering how, with the loss of the aforementioned awareness of what’s at stake in icon painting, things are bound to deteriorate into a mere color by number approach. But there is also fear, fear of the infiltration of modernist influences that will lead to a corrosion of a “timeless” atmosphere in ecclesial art. On the other hand, we should also ask if this perceived “timelessness” is nothing other than an illusion – stagnation taken as the stamp of genuine sacred art. Is this “timelessness” the preservation of anachronistic specimens in the formaldehyde of legalistic formalism?

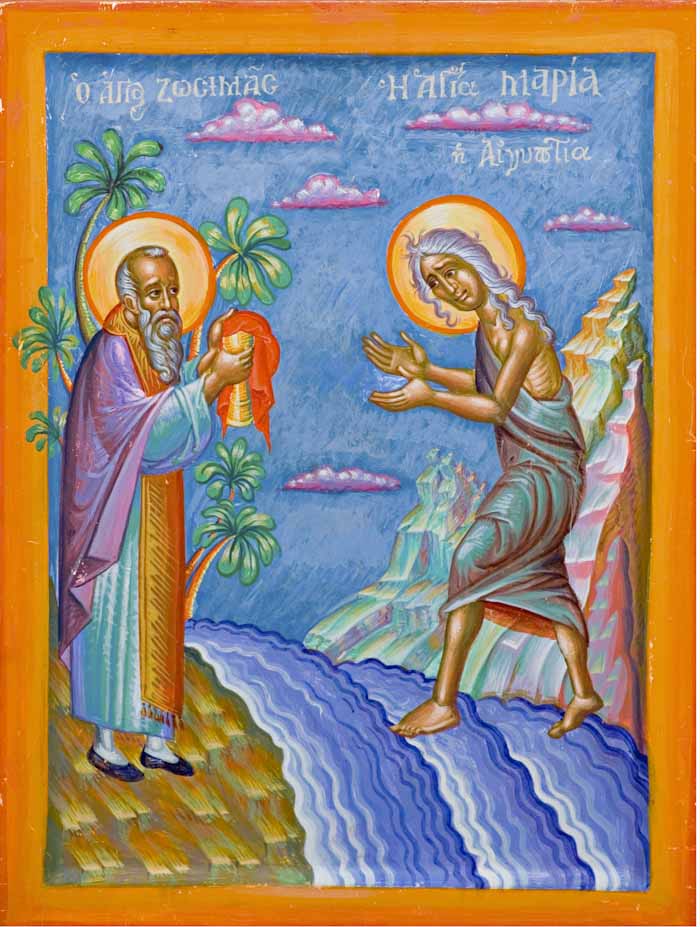

St. Mary of Egypt and St. Zosimas, by Fr. Stamatis Skliris.

Regardless to our answers to such a question, the fact remains that the work of Fr. Stamatis stands as a challenge to the contemporary iconographer. Some deride, others applaud his approach. In either case not always, I’m sure, for the right reasons. We might not ascribe to his ideas or even “like” his work, but the point here has been exactly to go beyond our likes and dislikes, as an exploration meant to dispel the stupor and complacency of the rigid aesthetic categories taken for granted as “correct” in icon painting. One of the things we can get out of Fr. Stamatis’ work is that it’s worth resisting the fear of experimentation in icon painting, a fear that stems from simplistic notions of Tradition and that can lead only to a paralysis bearing false witness to ecclesial life. He’s to be respected for the valor and ascetic effort he’s demonstrated in his commitment to icon painting throughout the years. Not all results might work, but many, nevertheless, manifest the living reality of the Church enlivened by the grace of the Holy Spirit – full of authenticity.

For further information and examples of Fr. Stamatis’ work see his website.

Notes:

[i] For a collection of Fr. Stamatis’ articles and many examples of his work see, In the Mirror: A Collection of Iconographic Essays and Illustrations, (Western American Diocese Press, 2007).

[ii] Sailors of the Sky: A conversation with Stamatis Skliris and Fr. Marko Rupnik on contemporary Christian Art, ed. Fr. Radovan Bigovic, trans. I. Jakovljevic, Fr. G. Edwards & A. Krstic, (Sebastian Press, 2010), pp. 21-25.

[iii] As quoted in Fr. Stamatis’ website, http://holyicon.org/, accessed March 23, 2020.

[iv] C. A. Tsakiridou, Icons in Time, Persons in Eternity: Orthodox Theology and the Aesthetics of the Christian Image, (Ashgate, 2013), p. 139.

[v] Sailors of the Sky, p. 25.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Fr. Stamatis Skliris, “The Icon as a Unique and Inimitable Fact in the Church”, Pemptusia (August, 24, 2014), accessed March 23, 2020. Our emphasis.

[viii] Ibid. Our emphasis.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid. Our emphasis

[xi] Ibid. Our emphasis.

There is a very great deal I could say about the shrill, psychedelic, grotesque “icons” painted by Fr Stamatios Skliris, but I shall limit my response to this:

An iconographer is not a slave to artistic fashions which change constantly, he works in service to, and under the direction of the Orthodox Church. Too often in recent years, people have attempted to justify making aspects of Church life and practice “more relevant” to a “modern society”. OK, then that means it’s time we had rap music liturgies to encourage young people to turn up to church. Ridiculous? Of course it is! Christ and His Church are timeless and beyond time, “the same yesterday, today, and forever”. Innovations, be they in liturgical practice, iconography, or other areas of Church life MUST be within the teachings and the Holy Tradition of the Church, and develop organically, not on an individual’s whim or fancy.

Man does not need a modern message since he cannot comprehend the ancient one.

Thanks Jill,

I understand your apprehension and agree with you on the dangers of hankering after innovations in an attempt to be “more relevant” to a “modern society”. So the point in discussing the work of Fr. Stamatis has not been to promote a total disregard for Tradition or the teachings of the Church. Rather, the point has been to see how the work of Fr. Stamatis serves as a healthy challenge to our simplistic notions of what fidelity to Tradition means in the realm of icon painting. It seems to me that we cannot limit “traditional” icon painting to a merely mechanistic or “color by number” approach, which totally drowns the personal temperament of the iconographer. As St. Paul tells us, the Body of Christ is composed of different parts, that is, unique persons with unique gifts, all contributing to the edification of the Church. Indeed, the goal is not to embrace “creativity” at the expense of the liturgical function of the icon. But we cannot forget that the two are intertwined. Stylistic variety in the life of the Church throughout the centuries attests to this fact. Moreover, we should recall that the Church has never proscribed nor prescribed stylistic formulas. In other words, the Church in her wisdom has never “dogmatized” on style. In the end, the icon painter, if he really wants to follow the approach of his forebears, has to make unique choices in his creative act that are good pictorial solutions to the challenges of his given circumstances. It is inevitable. This, of course, involves aesthetic choices that aim to embody a theological perspective which reflects the mind of the Church. Whether the results are appropriate or not the Church will decide. Yes, the Church is timeless, yet it touches time and participates in the cultural realities of history. Hence the creative endeavors of its participants will inevitably reflect their historical moment. This is neither good nor bad, but just an unavoidable fact. Fr. Stamatis might go too far at times, but his work cannot be easily dismissed as a denial of the mind of the Church. He has just been brave enough to experiment in ways that are unprecedented and jolt us out of our comfort zones.

Dear Jill,

A lot of us folks left behind the inanity of the bizarre and shocking in life when we converted to Holy Orthodoxy. Speaking as one of those folks, we are drawn to the Truth of what lasts; what is more of a universal in the life of the Church. Perhaps we’re just shallow in our adherence to tradition.

As common, average lay people and clergy, I find we want to learn and live out this tradition as given. Personally, it becomes a huge burden riddled with no amount of confusion when we encounter such a “push” to experiment and “progress” things in our tradition. Innovation is nothing new though, so I look to Church history to for an answer to these kind of things. It’s pretty clear that overtime, most innovations just kind of fall away. What’s universal sticks. I plan on not paying much attention to the innovations. If it’s meant to stick, it’ll have to last longer than I live anyway.

Thank you, Fr. Silouan, for bringing the unusual work of Fr. Stamatis to my attention. I read this with great interest, thinking about why there is such a likeability problem with his work, despite the many merits of his painting.

Personally, I like some of his work very much. The ones I don’t like are the ones that use extremely saturated colors with a preference for colors that are quite rare in nature, like hot pink and neon orange. It strikes me that there are two errors in the theoretics that Fr. Stamatis uses to justify this work. One problem is the assumption that the work of avant-garde French painters from over a century ago somehow characterizes the aesthetics of the modern age. These painters have their rightful place of honor in the history of western art, but their styles came and went relatively quickly, and their penchant for bright colors did not universally persist in the visual art of the century following them. Nowadays, we happen to live in a period when super-low saturation is endemic in many fields of art. Luxury interiors are all white and gray, and big-budget action movies are filmed with an almost colorless palette, for instance.

A second error is to treat icon-painting as a self-contained art. By the time the post-impressionists were painting, it had become possible to create canvases whose sole purpose was to hang in an art gallery – a space in which a painting need not coordinate with anything else. But an icon or fresco scheme has to fit into a wider aesthetic shared by all the other stuff in a church, and by the culture of those who use the church. Now there are places in the world where super-high-saturation colors are normal in churches (some parts of Central America, Ethiopia, India), and there’s nothing wrong with that. But to impose such colors in a place and culture where they aren’t normal creates inevitable discord and distraction.

On the other hand, there is a case to be made for pushing colors a bit brighter than people are used to. After all, what people are used to is often soot-stained churches, old icons with yellowed varnish, and sun-bleached prints. Historically, colors were brighter than we now think. I can respect Fr. Stamatis’ efforts to bring vibrancy back into liturgical art, though I would prefer to frame it as revival as much as modernism. Looking at that way can help us understand which experiments stay within the margins of tradition, and which go completely outside it.

Well put Andrew. I think that your two observations about the theoretical problems are very important. And, yes, I agree with you that, when it comes to Fr. Stamatis’ efforts to bring vibrant color back to liturgical art, it is best to “frame it as revival as much as modernism.”

Perhaps instead of reading Fr. Stamatis’ engagement with modern painting as a matter of somehow adopting what constitutes a “modern look”, we can look at it as a way of experimenting with those aspects of modern painting which converge with the pictorial concerns of the icon.

Thus, for example, I think that for Fr. Stamatis the main concern with color has to do with its capacity to convey a visionary sense of eschatological Light and Paradisiacal joy and exaltation. His main model for this is the vibrant and saturated color harmonies of Vincent van Gogh, in which we get a sense that nature is perceived as a theophany. Van Gogh once wrote to his brother Theo: “I want to paint men and women with that something of the eternal which the halo used to symbolize, and which we seek to confer by the actual radiance and vibration of our colourings.” Perhaps Fr. Stamatis has taken on this challenge and exploited saturated color as a means of somehow capturing pictorially a sense of the uncreated Light, permeating everything in the cosmos with pulsating intensity.

Your point about cultural/liturgical context and the icon not being a “self-inclosed” art is very important. I agree with you that “to impose such colors in a place and culture where they aren’t normal creates inevitable discord and distraction.” However, the fact that Fr. Stamatis has already painted many churches in his unique mode is evidence of a cultural sector and current within the Church that is open to his kind of work. The crucial question, as you note, is whether or not his idiosyncratic mode can be coordinated successfully with the other aspects of the liturgical context. But my sense is that whether or not something comes off as discordant and distracting has often more to do with cultural tastes and aesthetic education, than with theological problems per se. I think most of the time these two categories tend to get conflated in discussions about what is appropriate or not within a liturgical context.

“I think that for Fr. Stamatis the main concern with color has to do with its capacity to convey a visionary sense of eschatological Light and Paradisiacal joy and exaltation. His main model for this is the vibrant and saturated color harmonies of Vincent van Gogh, in which we get a sense that nature is perceived as a theophany. ”

It is revealing that Van Gogh is invoked here. He was an artist as much beset by darkness and dread, as he was in “pursuing the light”. When I first saw Skliris’ so-called icon of “St Andrew just before his martyrdom” a few years ago, these were my observations:

“This painting reminds me of Vincent Van Gogh’s self-portraits during his more tormented periods. There is no stillness or spiritual calm here, nor does it express the Apostle’s Christ-like acceptance of his impending death as a martyr as any good icon should, notably those of Christ’s crucifixion, the great exemplar of selfless and willing sacrifice.

Instead, we see a man engulfed in a whirl of gloom, turmoil and fear. There will be no victory in this Apostle’s death. This is all the more ironic, as the hymnography for the saint is full of references to his bravery. Andreia (courage, bravery, manliness) is the source of the name Andreas. The first-called apostle truly lived up to his name.”

Link to the painting: https://frmilovan.files.wordpress.com/2010/12/holy_apostle_andrew.jpg

How, then, can Skliris justify calling this disordered, troubled painting an icon? How does it conform with the teachings and ethos of the Church? How is it the visual complement to the Church’s hymns and prayers to Apostle Andrew? On what grounds can it be considered suitable for veneration? And, most importantly, how does it bring us closer to Christ and the things of God?

How can Fr. Stamatis call it an icon? How could he not? Icon is the Greek word for image. To a Greek-speaker, every picture is an icon. Your question implies a distinction between icon-images and non-icon images, but this distinction only exists in English. There is no cannon of the Orthodox church that asserts that some pictures of saints are icons and some are not, or that icons must depict saints in tranquility and not in anguish.

For certain, most icons for liturgical use do depict saints in heavenly tranquility. But the church and her liturgical art certainly does not deny that saints sometimes suffered anguish, turmoil, and fear. Jesus himself blessed this reality of human life when he called out on the cross “My God, why hast Thou forsaken me?”. We sing extensively of these dark emotions in the hymnography of Holy Week. And in the historical record of Byzantine icon painting, examples can easily be found that depict saints in emotional anguish. These have always been outliers, never the core of the painting tradition, but they were always present. To say that modern iconographers may only paint in one correct way is to misunderstand the breadth of experience that the church embraces in her liturgical art.

Does that mean I think that Fr. Stamatis’ icon of St. Andrew is the perfect archetype of the saint and should be given the place of honor on an iconostasis? Of course not. A liturgically prominent icon should be balanced and refined, both emotionally and technically. But is there room in some small corner of the church for an icon that shows a saint in his moment of fear and doubt before his martyrdom? And might this icon be a comfort for someone who himself suffers fear and doubt? Absolutely.

I think Fr. Stamatis’ work is most successful as iconography when the human figures are represented with subdued classical beauty and balance that is not far from the canon of traditional iconography, while the kosmos around these figures (and perhaps their garments as well) enjoy the exultant freedom of radiance and dance through movement and color. The image above of Adam naming the animals best exemplifies the potential of Fr. Stamatis’ approach in my opinion.

When saturated and high-contrast coloration techniques are employed on the flesh of the figures, it’s difficult to see those represented as the true likenesses of persons in the kingdom of God (as icons).

High coloration can also sometimes disguise poorly drawn/proportioned anatomy, which needs great attention in order to serve well the purposes of the icon.

with your prayers,

Baker