Similar Posts

Rashid and Inessa Azbuhanov are recognized as forerunners in the rediscovery of the carved icon and we have featured their work here before. This time we present a feature interview with the Azbuhanov couple thanks to the kind collaboration of Paul Stetsenko who translated the whole interview from Russian into English for us. The Azbuhanovs carvings circulate in the highest spheres of both Church and State with icons belonging to patriarchs, popes, royalty and the political elite. In 2014, they were awarded the Russian Federation National Award for arts and culture, which is the highest state honor attributed by the Russian state.

Their work separates itself into three categories: carved icons, architectural carving and modern geometric abstract compositions. The relationship between these three aspects is not always immediately obvious. Their architectural iconostasis carving is baroque with excellent execution yet with conventional 18-19th century design.

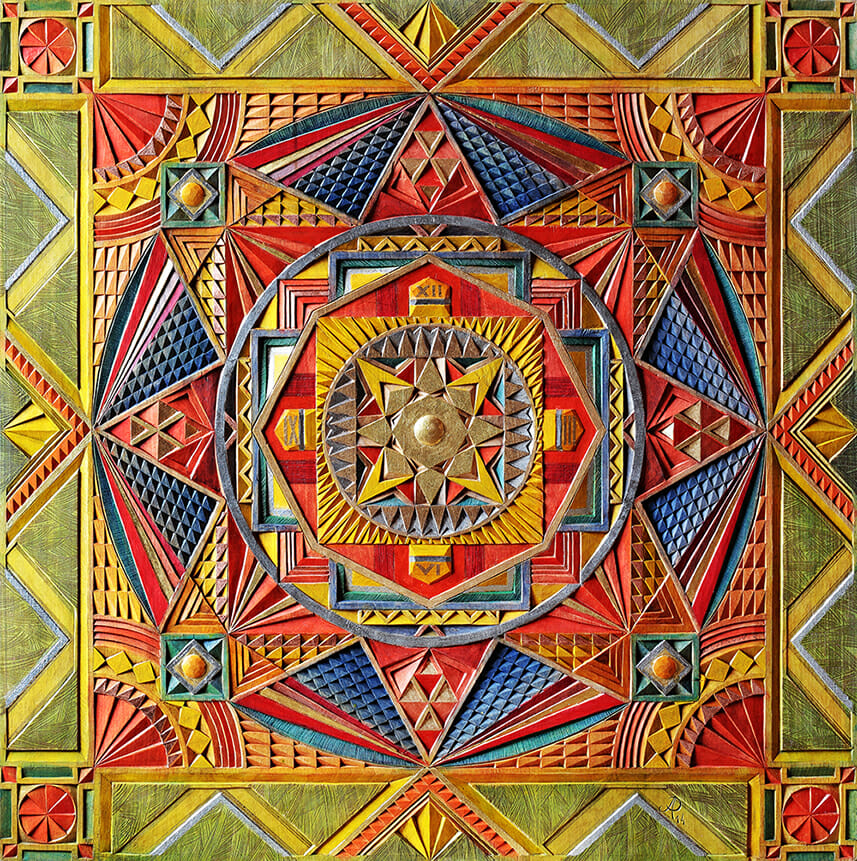

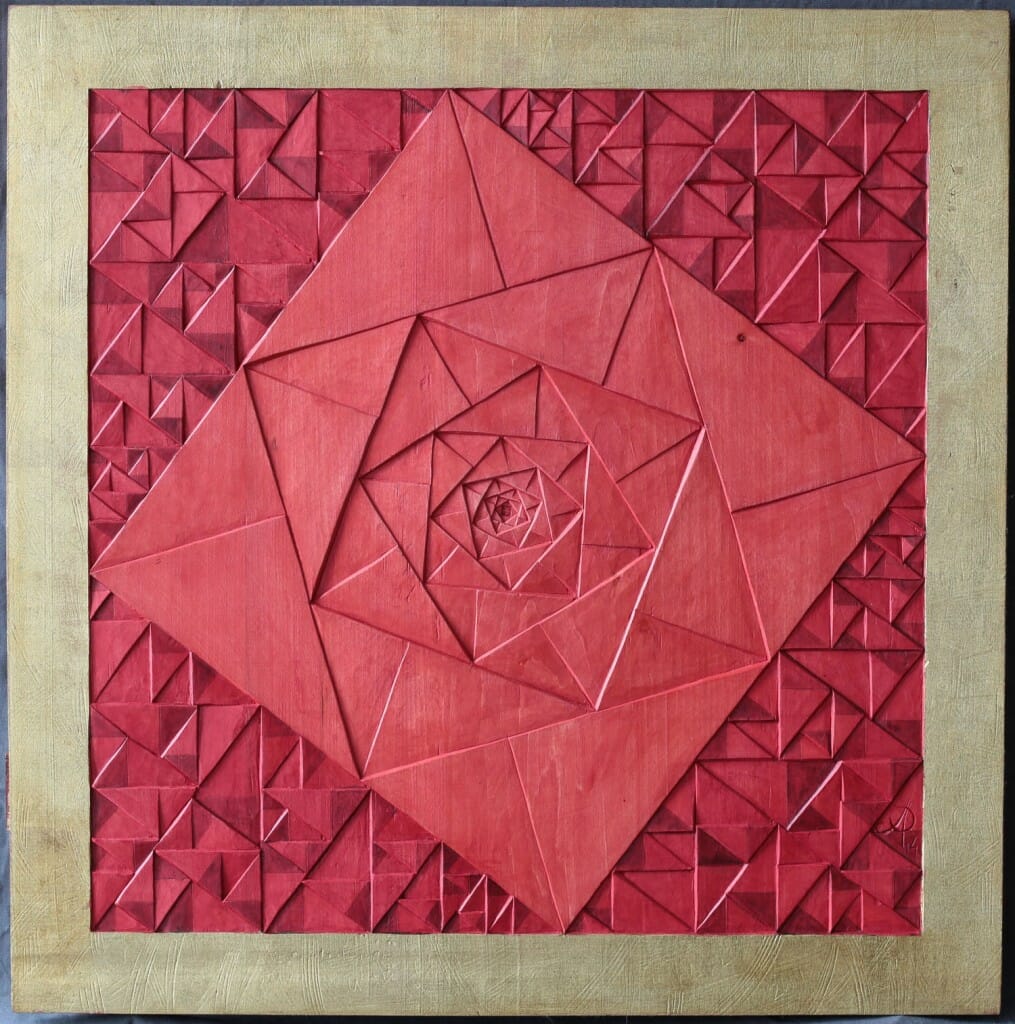

This contrasts quite a bit with their other work, especially their abstraction work which is more recent and seems to connect to early 20th century Russian Abstraction, but including more traditional and maybe even mystical geometric symbolism in which are fused crosses, mandalas, stars and other shapes which have religious connotation. These abstract works are a fascinating crossroads because they are undeniably gallery art, that is they are not objects of specific use as is the case of liturgical art, and they obviously refer to Avant-Garde abstract art, which came at the height of “art for art’s sake”, yet they also seem to play with or push the tenets of modern abstraction which usually invoke the self-sufficiency (autonomy) of art.

The compositions in their abstract carvings are most often concentric, hence the references to crosses and mandalas but there is also a reference to pattern. Pattern is something that modern abstraction abhorred, and in contrast it had been the main vehicle for geometric abstraction in the Middle Ages and remains so in other traditional cultures. This point in itself conceals all the difference between a traditional world view and our contemporary societies. So through structural elements and through execution in wood with chip carving, the Azbuhanov’s geometry also suggests folk ornament. Yet these relations to folk art and pattern in their work are taken to a high level of fully resolved imagery, which through complex constructions make each carving stand on its own as a composition.

The reinsertion of an ornamental charge in geometric abstraction is both a return to tradition and simultaneously a post-modern gesture as it undermines the totalitarian purity of Russian abstract artists such as Malevitch with reference, meaning and even some excess. They call this work “metasymbolism”. an interesting appellation that might in some ways contain the ambitious goal of these carvings, an ambition which becomes even more apparent when one notices some of the titles which can be surprisingly descriptive and seem to suggest that they are also attempting to express a level of narrative in their abstraction as well.

The work for which the Azbunanov couple are most known and on which we want to attend with greater weight is of course their work on carved icons. Just as in their abstract work though, in their icons we find the traditional canons of the Icon fused with folk elements and chip carving patterns. Pattern and ornament play essential roles in their composition and the result is a bold synthesis of strong composition and dynamism (especially in clothing) with decorative surfaces. I had the chance to start exchanging with the Azbuhanov couple several years ago, and I am honored they have agreed to answer a few questions about their work for us.

Pageau : As a couple you are known as the forerunners in the rediscovery of the carved icon, and recently you have been given the highest honours in Russia for your life’s work. But when you started, at that time when the carved icon was almost unknown in the world, what prompted you to engage this art?

Azbuhanov: Initially, we were not trying to revive the art of carved icons. Back when we were students at the art school (1979-1985), Rashid studied the sculpture (wood-carving), and Inessa studied ceramics. Rashid has always been more attracted to bas-relief than to sculpture, and he loved working in this technique. After graduation, Rashid worked for the Church, making altar furniture, lecterns, and iconostases. It was a difficult time, the time of atheism in Russia. In 1989, we were commissioned to make a copy of an ancient bas-relief of St. George the Victorious. Rashid was struck by and attracted to the laconic, fluid lines of that carved image. That project jump-started our research in this area and prompted us to seek out the literature on the subject. Unfortunately, much of that literature had been lost; however, the curators of the State Historical Museum in Moscow introduced us to many wonderful and beautiful examples of this unique art. Incidentally, this museum houses a large collection of carved icons.

Pageau: Your icons seem to fuse high aesthetics of classical Byzantine art with a more folk sensibility of pattern and composition. Can you tell us a bit about your approach to image making and how you created your specific style?

Azbuhanov: Rashid did not limit himself to making copies; we decided to move beyond that. We were fascinated by the subject itself and the processes involved. We can say that using the the well-known icons as a starting point, we began to make our own choices and to introduce our own solutions, all the while not straying from the iconographic canon. Rashid has brought to it a lot of imagination; for instance, he added ornaments to the garments of the saints and elaborated the backgrounds with simple geometric patterns in chip-carving. Thus, in the early 90s a new style began to emerge in our work, a trend which was neither accepted not understood by many. We went through a phase of experimentation: we experimented with natural stones, metals, fabric (brocade), and various dyes such as dark-brewed tea and other herbs. But in the end, we settled on monochromatic carving in which clean and unadorned wood is striking in its own beauty. We also used delicate, unassertive gilding, just to emphasize important accents and the saints’ halos. When we worked with color, we only used natural pigments and gold leaf. Starting with the 90s, we have mostly utilized linden tree as this material has great plasticity and a uniform, nearly glowing white texture without streaks. Besides linden tree, we used pine with its rich texture, and also Siberian cedar.

Pageau: .The Carved wooden icon has been a vibrant part of Russia’s living relation to the Holy Traditions of the Church. Yet we know that carved icons were sometimes opposed and were even banned at some point by Peter the Great. Did you encounter resistance when you tried to revive this lost art?

Azbuhanov: Naturally, we encountered resistance and lack of understanding. It is fairly typical to encounter such rejection when doing something new and unusual, especially when working within a canon. We were told, “This cannot be… that should not be done… etc.” This rejection was coming from both the clergy and the artists working for the Church. They had a hard time accepting that the times were different now, and that the artist has a right to have his or her say. Besides, we never called our work “icons.” Instead, we called it “reliefs on Christian subjects.” However, we gradually transitioned to liturgical iconography and began accepting commissions for the Church. At the same time, we collaborated with Russian museums, exhibited our work in art galleries, and soon even art critics began to refer to our works as “iconography.”

In 2001, Patriarch Alexiy of Moscow opened our personal exhibit; and right at that exhibit, one of our icons, Theotokos of Speedy Counsel, became fragrant and started streaming myrrh. The Patriarch said then, “This is just an ordinary Orthodox miracle.” He carefully examined the carving and established that it was indeed true myrrh-streaming. That was when His Holiness called our work an “icon”, after which all discussions regarding its canonicity became academic. The Patriarch also gave us great support and blessed us when we were preparing our exhibit at the Vatican. In 2004, thirty of our carved icons were displayed in the Vatican Palace and subsequently at the Lateran Palace. The Vatican critics’ reviews were highly positive, and there were many articles in newspapers both in the Vatican and in Rome.

Pageau: Knowing that you work together as a couple, I am curious to know how you do this? Do you both work on each image? Do you have specific things each of will make on each icon?

Azbuhanov: To answer the question on how we work, is not easy. We are both professional artists. Rashid often chooses the subject and implements the carving. Inessa picks up the idea, makes course corrections, and finished the work in color.

Pageau: When you look around at Orthodox art today, both in Russia and other countries, both liturgical and “secular”, what vision do you have of what is happening?

Azbuhanov: AzbuhanovWhat is our assessment of the contemporary state of the Orthodox art in Russia? Rashid’s comment: the stagnation of 70 years of Communism has had its heavy toll. The Church art’s revival has been not without strangeness. Icons, frescoes, and mosaics have all been rooted in old traditions; yet temple art is somewhat chaotic, and it also does not relate to our time. There are lots of formerly abandoned churches in Russia, churches that are now being restored. However, they often restored in a way that is incongruent to the style of the building; there is plenty of eclectic mismatch, and the voices of professional artists are often disregarded.

Pageau: What advice would you give Christian artists who want to use their abilities either for the church or for non-liturgical art?

Azbuhanov: The artist’s talents are God-given; these should be used in full to the glory of God. All works that artists create need to be shown to people; they need to be marketed and sold so that the artist has opportunity to develop and move forward. One should not be afraid of trying new and modern materials and technologies; after all, we live in the 21st century, and it is a brave new world.

For those interested in looking further into their carving. they have recently put up a Youtube channel which features documentaries (in Russian) on their art. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCGrGxFW7TwNUDU6i5geVB-w

Pictures are also available on their website: http://azbuhanov.ru/

I’m STUNNED by these images! They’re beyond beautiful. “Heavenly” is the word that immediately comes to mind – and I mean that literally. They are extraordinary gifts for our eyes and souls. Thank you so much for this!

Jonathan,

Thank you for the excellent article. And many thanks to the Azbuhanov couple for the interview and the beautiful works.

One correction: above is SS Florus & Laurus (not SS Boris & Gleb).

In Christ,

Hierodeacon Parthenios

Thank you Hrdcn Parthenios. Silly mistake on my part. Got thrown off by the horses.

Beautiful.

Thank You.

Thank you Jonathan for an amazing article! I will be printing this one for Barbara!

My wife has pointed out that the abstract panels shown in this post are only ‘modern abstract art’ if they are hung on a gallery wall. One could just as easily use them decoratively – for instance, as the bottom panels on an iconostasis. In that case they would be innovative (and yet still traditional) decorative carving.

I wonder if the Azbuhanov’s have considered making a whole iconostasis – both the icons and the structure – in their style. I can well imagine their polychromed relief carvings as the icons and their polychromed chip-carving as the ornamented structure. Such an iconostasis would be quite a feast for the eyes!

Coincidentally, my next post is going to be on the subject of polychrome for iconostasis carving and other decorative woodwork.

Interesting. They certainly conceive of these as gallery art, with titles and complex references and what not, so no I don’t think they have thought of making an iconostasis with that style. I think even their icons, though properly considered icons are mostly in private collections and not used in churches as such. That is at least what is suggested on their website.