Similar Posts

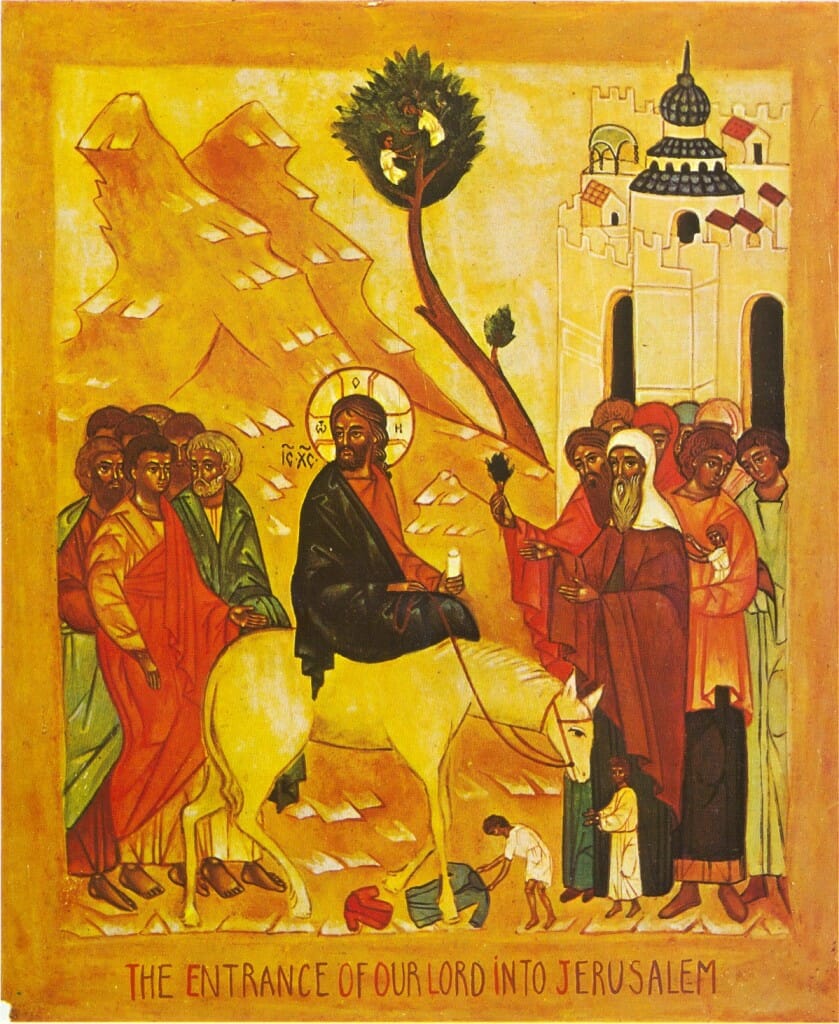

We are so used to seeing the features of Christ in icons that we no longer pay attention to them, thinking they have always been there, as we see them, taking them for granted. We have perhaps forgotten that behind each feature there is a history and a theological meaning to discover and rediscover. So it is for the three Greek letters found in Christ’s cruciform halo.

These letters form the present participle, ὤν, of the Greek verb to be, with a masculine singular definite article, ὁ. A literal translation of Ὁ ὬΝ would be “the being one,” which does not mean much. “He who is” is a better translation. These words are the answer Moses received on Mount Sinai when he asked for the name of him to whom he was speaking. In Hebrew, he who was speaking said Yahweh, which is also a present participle. Greek translators of the Hebrew Bible put Yahweh as Ὁ ὬΝ.

Before I began to study this subject, I also thought that these letters had always been part of the image of Christ, but in examining the images that have come down to us from the first millennium, and even after, I noticed that the Ὁ ὬΝ is universally absent, as much in the West as in the East. I therefore started searching for the answer to the following questions: when, where and why did Christians add these letters to Christ’s halo?

I began by noticing that during the first millennium, Christ’s halo was sometimes empty and that, more rarely, it was absent.

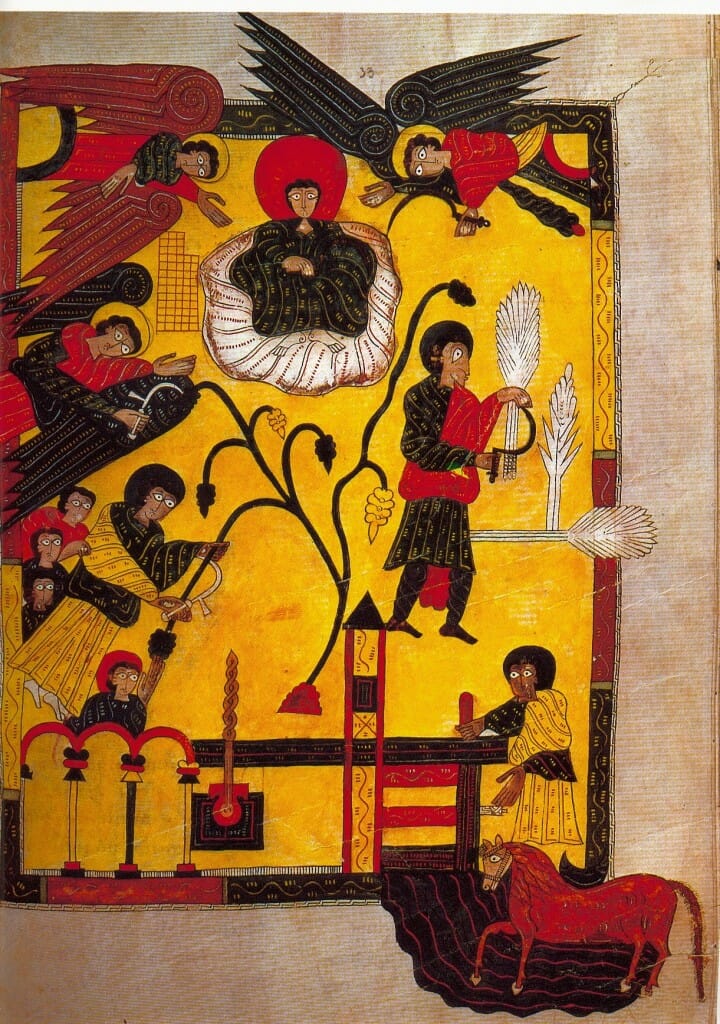

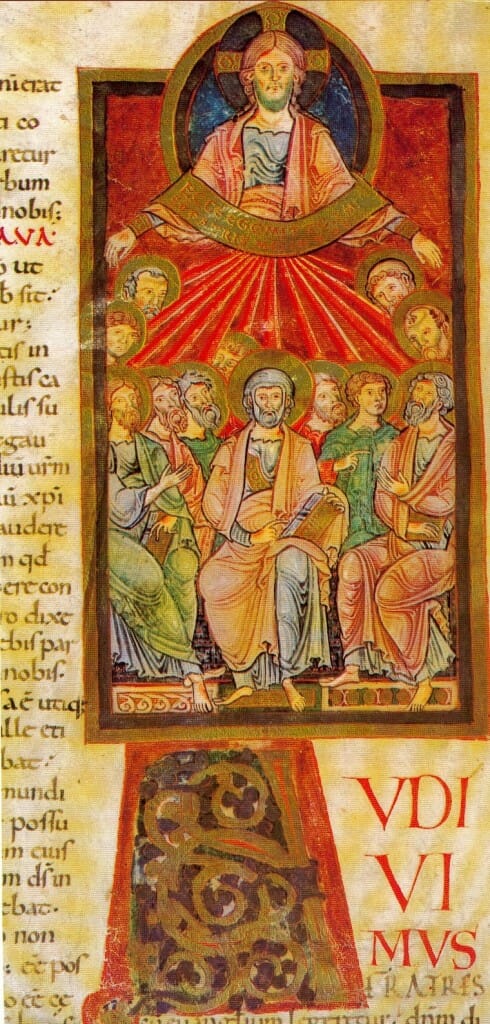

The Last Judgment, Beatus, Illuminated Parchment Said to be from the Escorial, Monastery of San Millan de la Gogolla, 950-1000, Monastery Library, St. Laurent de l’Escorial.

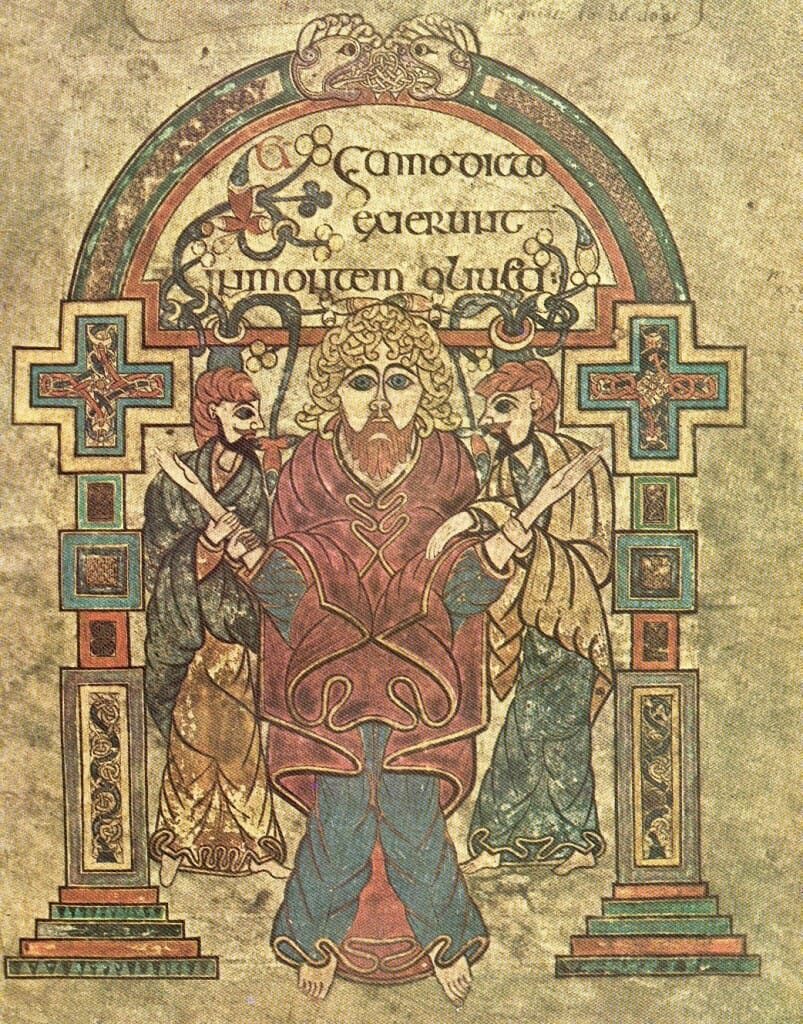

The Arrest of Christ, The Book of Kells, around 800, The Library of Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland.

Other images show a kind of “decoration,” but without meaning.

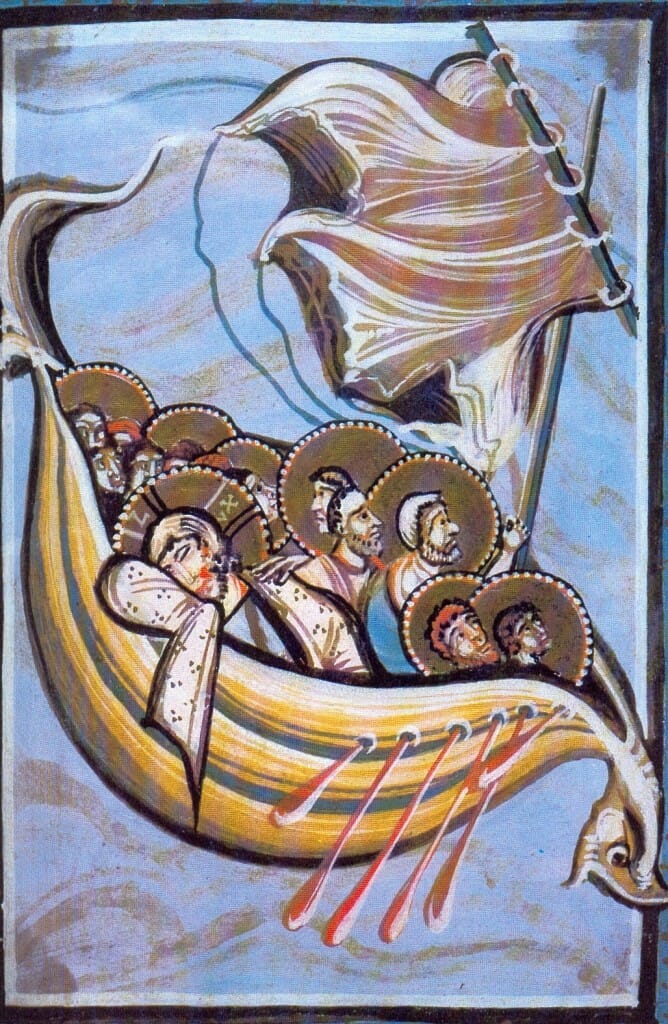

Christ in Majesty, Illuminated Parchment Gospels of Gundohinus, 754,Municipal Library, Autun, France.

A few though, appear with words inscribed in the halo, but now with more theological signification than simple decorations: LUX, PHOS, REX [and] JUDEX. But Ὁ ὬΝ? Nothing.

![16. Christ Pantocrator in the Tympan the Church, Conques, France, 9th Century.17. Zoom, Cruciform Halo : REX [et] JUDEX](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/02125406/16-768x1024.jpg)

16. Christ Pantocrator in the Tympan the Church, Conques, France, 9th Century. 17. Zoom, Cruciform Halo : REX [and] JUDEX

18. The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, Gospels of Hilda of Meschede, Cologne School, 1000-1020, Hessische Landesbibliothek, Darmstadt, Germany. 19. Zoom, LUX in the Cruciform Halo.

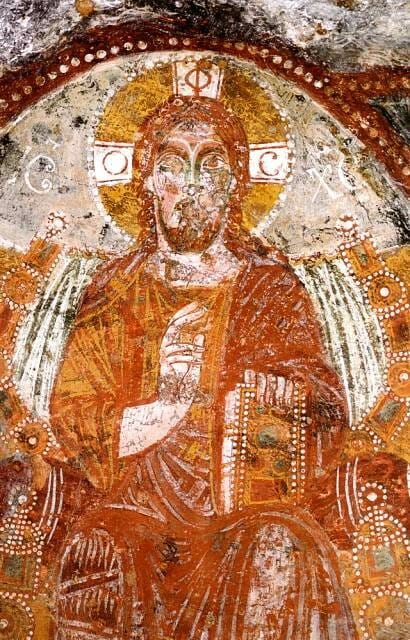

Cruciform Halo with PHOS. Christ Pantocrator, Fresco, Church of Sante Marina e Cristina, Carpignano, Italy, 12th Century.

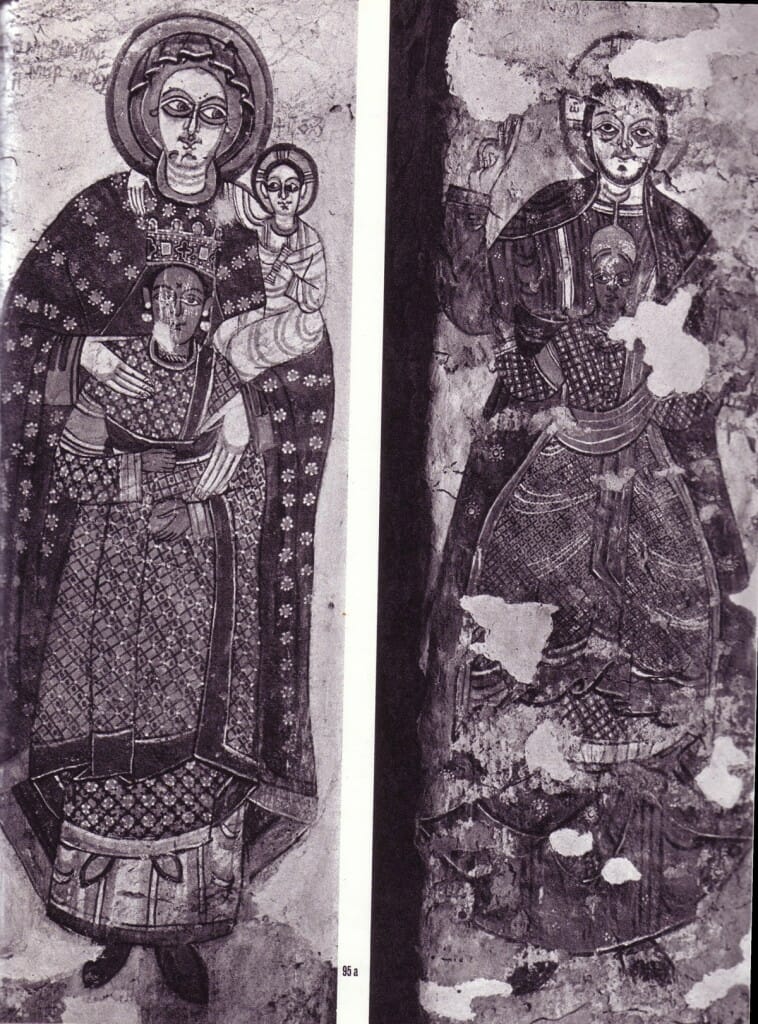

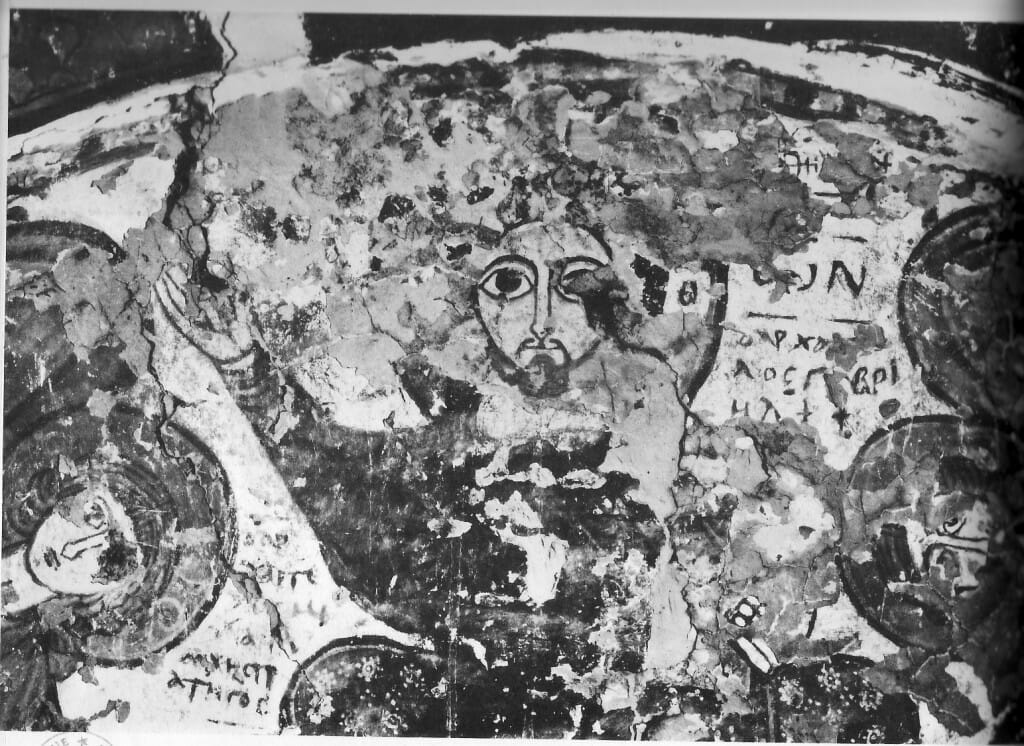

According to my research, the first examples of Ὁ ὬΝ in Christ’s halo appeared in Egypt in 1130, and in Nubia in 1150. We know of these examples thanks to recent archeology. It is improbable, because of the isolation of these countries at this time, that these images would have had any influence on the rest of Christendom. We must nonetheless remain prudent, since archeology can still surprise us.

Christ Protects a Nubian Prince, around 1150, The National Museum of Warsaw, Poland. Note the Omega, ὤ, on the Left. The Two Other Arms of the Cross Are Damaged, But We Assume the O and the N Were There.

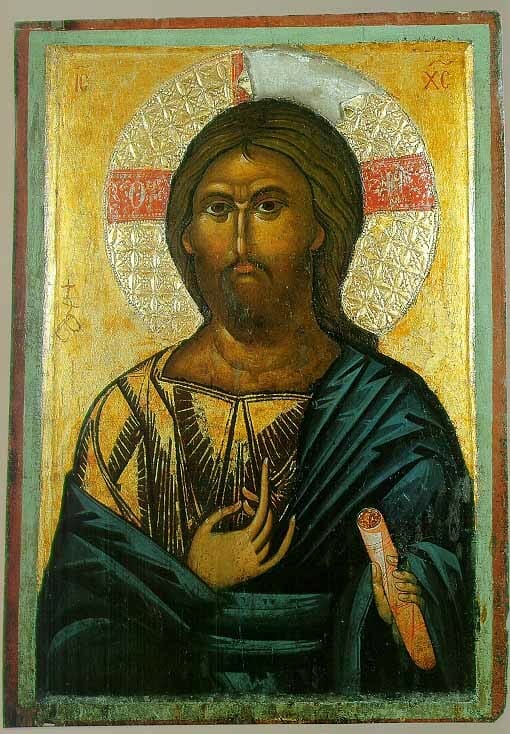

So it seems that the first images of Christ with Ὁ ὬΝ in his cruciform halo originated from Slavic countries, the Balkans and maybe Russia.

*Nerezi in Macedonia, 1164[1]

*then comes an image of Christ Savior, Macedonia, dated at 1250[2]

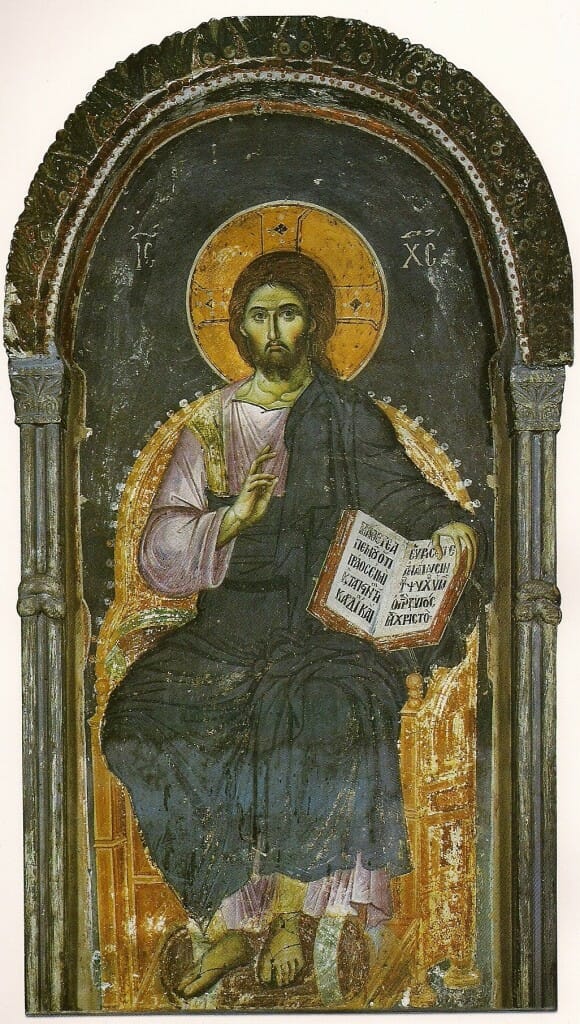

Christ Pantocrator, a Gift to Archbishop Constantin Cavasila of Ohrid, Church of the Peribleptos Virgin, St. Clement, 1262.

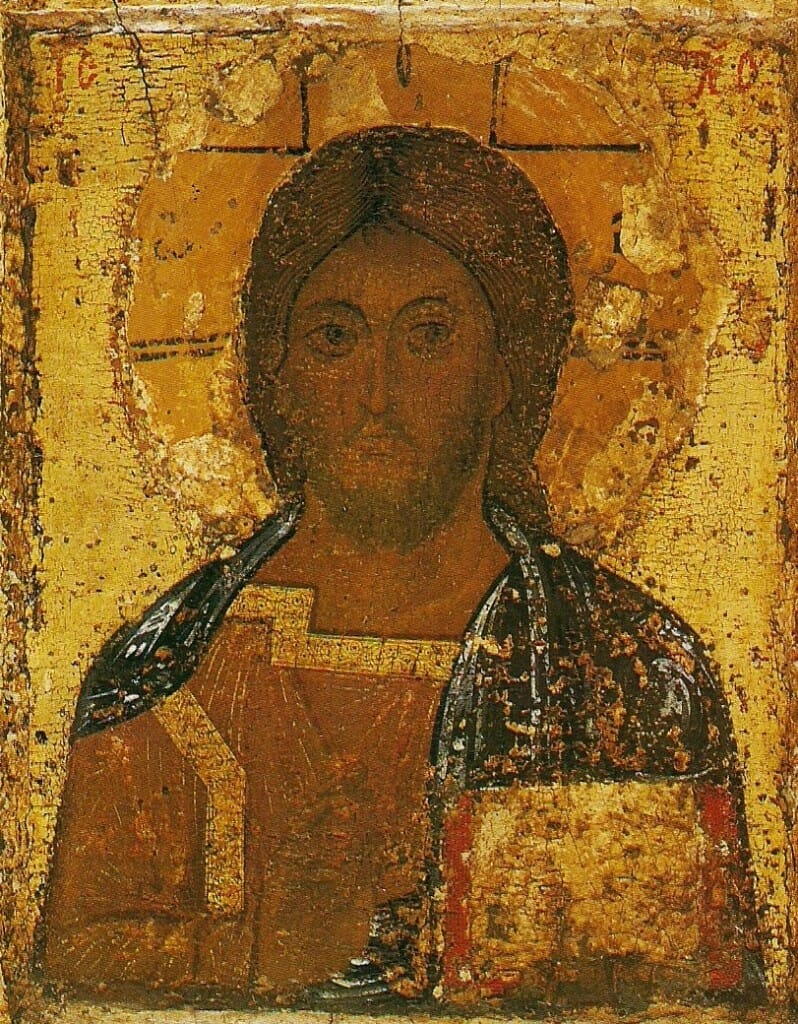

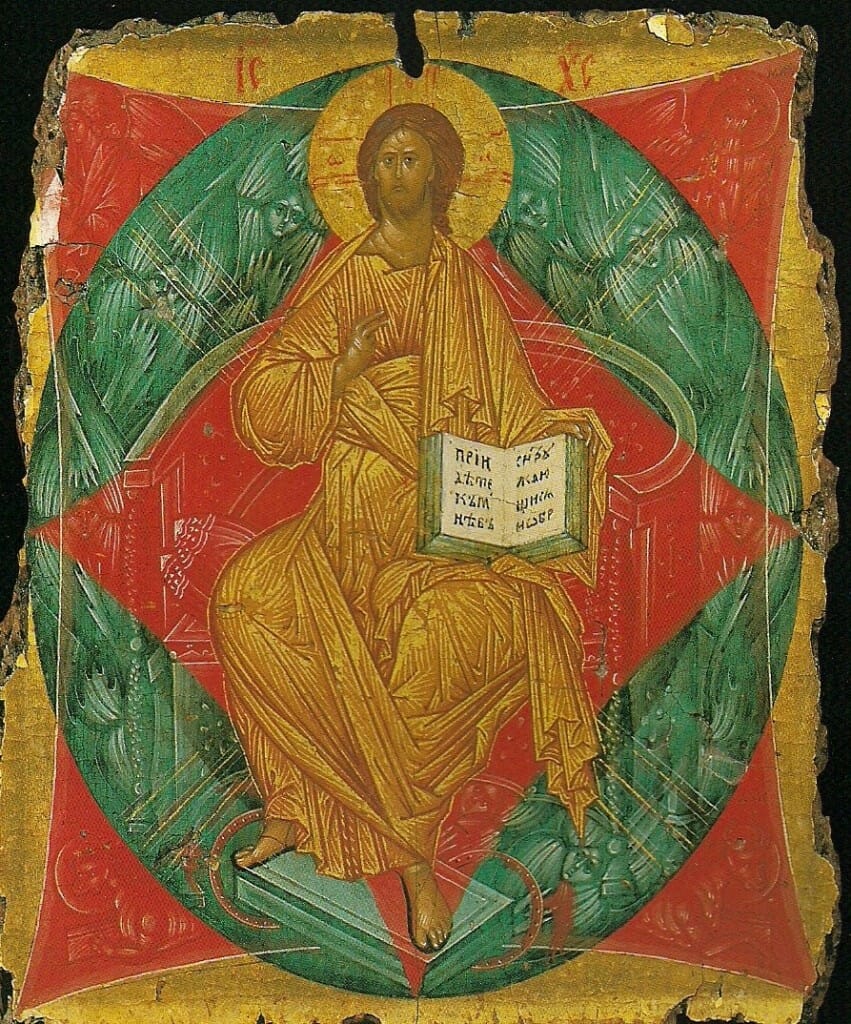

*following is an icon of Christ Pantocrator, Iaroslav, Russia, 1250 [3].

*According to the images in the Protaton of Mount-Athos, Manual Panselinos, who painted them in 1290, did not know Ὁ ὬΝ[4], but the “painter of the Mount of Olives” to whom are attributed the frescoes in the exonarthex of the Vatopedi Monastery, 1312, knew of it[5]. Therefore between these dates, an artist that knew of Ὁ ὬΝ came to Mount Athos ;

*in the fifth position, we have the image of St. Nicholas, by Alexis Petrov, 1294, Novgorod[6] ;

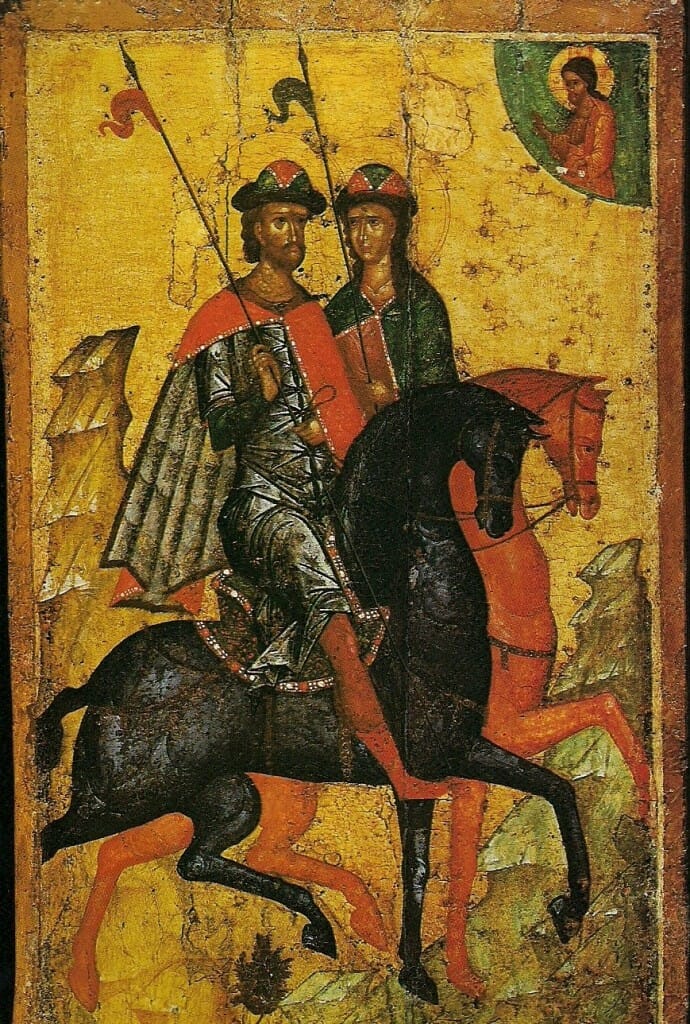

*the image of Sts. Boris and Gleb, around 1350[7];

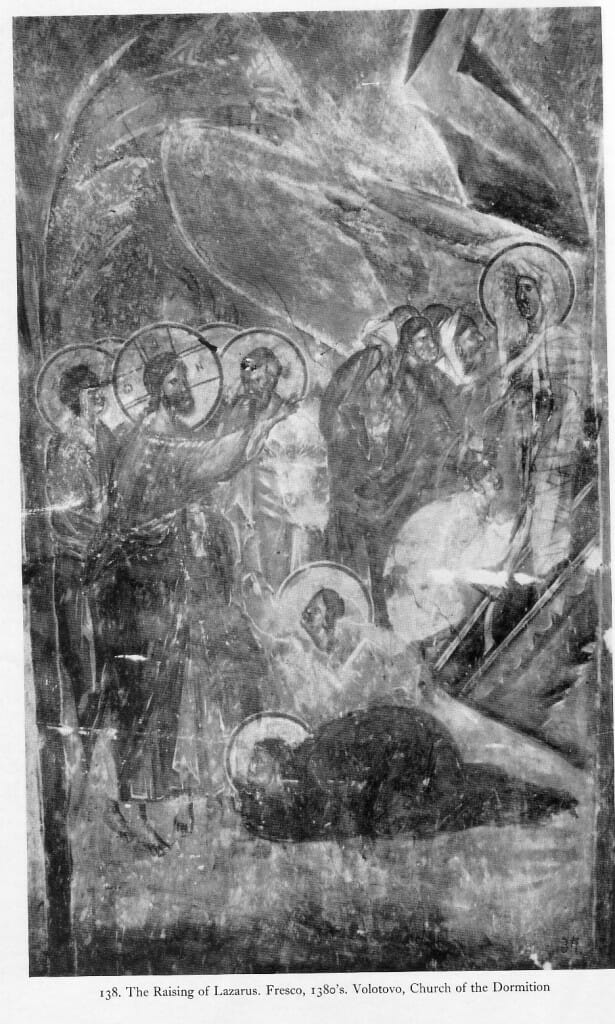

*the frescoes of Volotovo, near Novgorod, Russia, 1380[8](images 40-41);

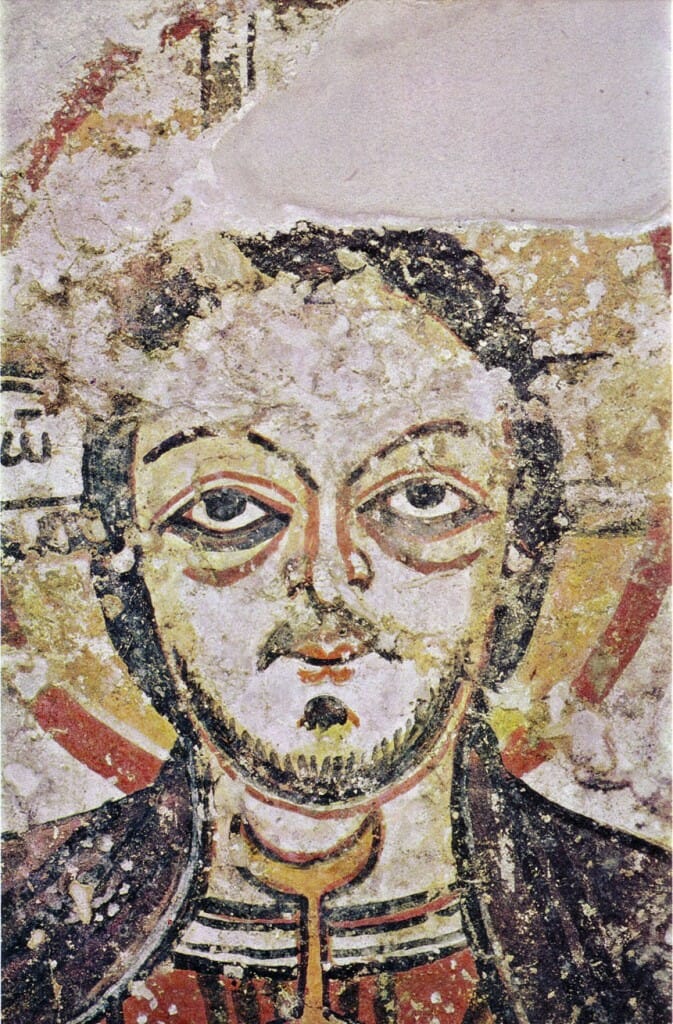

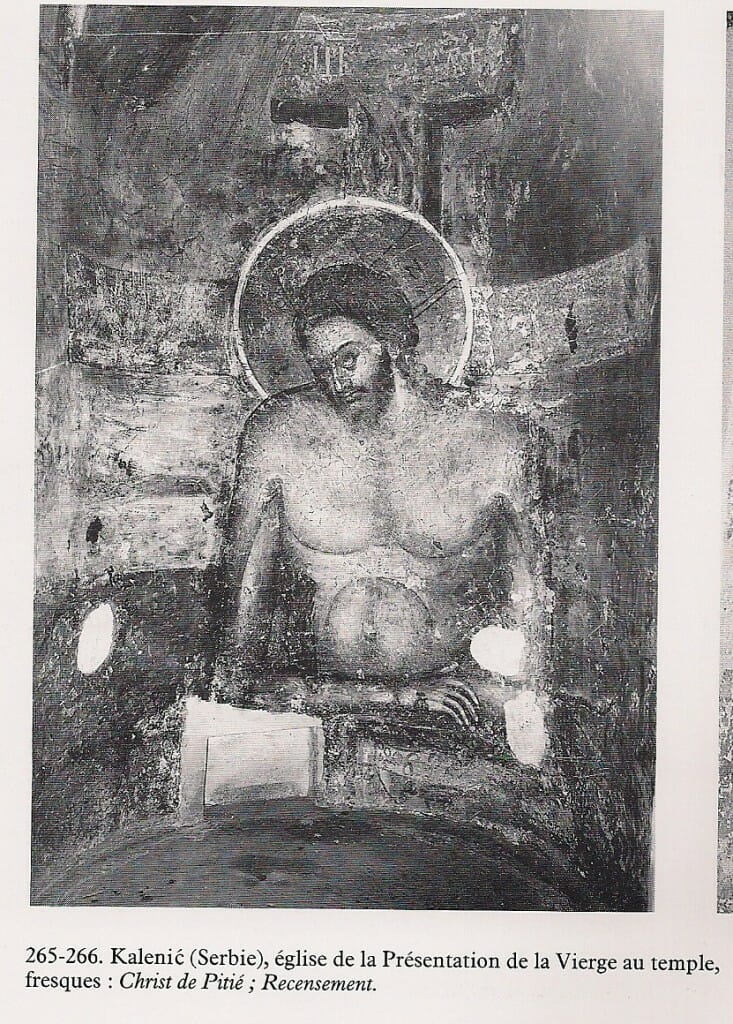

*in Kalenic, Serbia, 1420, Christ in pity, niche of the Prothesis[9] ;

Christ the Man of Sorrows, the Church of the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, Kalenic, Serbia, around 1410.

*apparently, St. Andrei Rublev knew of this trait but used it only rarely[10]. (images 44-45).

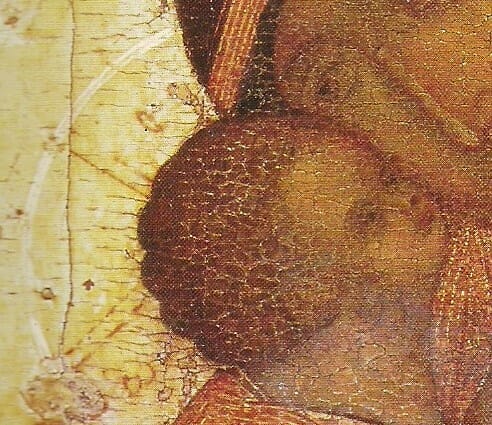

On the image printed in the same book, we are not able to see the Ὁ ὬΝ[11](images 47-47),

but with Victor Nikititch Lazarev[12](images 48-49) claimed that the Ὁ ὬΝ is visible.

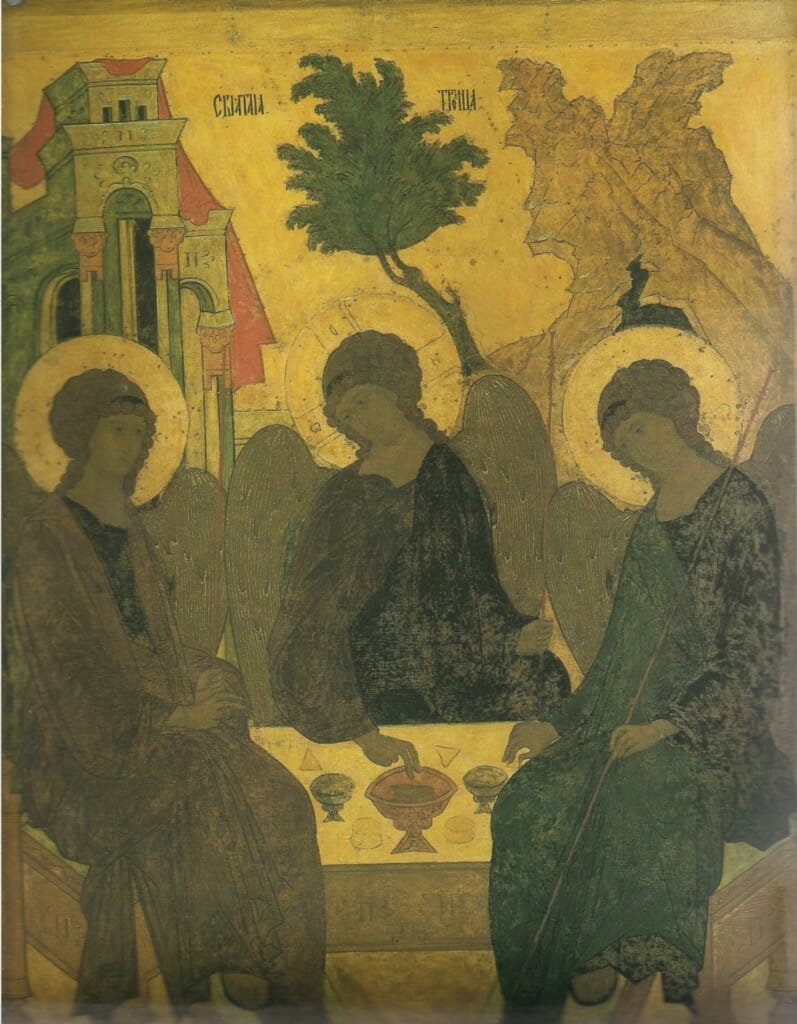

See also the curiosity[13](images 50-51) where on a copy of Rublev’s Trinity, the monk Païssi placed Ὁ ὬΝ in the cruciform halo of the central angel, testifying to a Christological interpretation of the Hospitality of Abraham rather than the more common Trinitarian interpretation.

If our hypothesis is well founded, and the Ὁ ὬΝ in Christ’s halo was born in the Balkans or in Russia in the first centuries of the second millennium–having then answered the question “where” and “when”–we can move on to the question of “why”[14]. Many historical testimonies (see bibliography) indicate that at that time the Orthodox Church fought ferociously against the Bogomil heresy, a dualist sect that rivaled the established Church. The Bogomils, among other things, rejected the Old Testament, saying it was the revelation of the evil god, and accepted only the New Testament that revealed the good god, the Father of Jesus. Since Marcion in the first centuries, the Orthodox have always rejected such a doctrine. How can Jesus be the Messiah of Israel, announced by the prophets and seen in theophanies by visionary Jews, if Christians, the new Israel, have no link with the Old Israel? And so, what could be a stronger affirmation of the close link between the New and Old Testament as well as of the identity of the God of Israel and the Father of Jesus than putting Ὁ ὬΝ in the cruciform halo of Christ? The theological affirmation becomes obvious: he whom we see in the image, Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified, who died and was raised from the dead, this same person is precisely the same one who told Moses on Mount Sinai that his name was Yahweh (Ὁ ὬΝ).

On the other hand, I found a reference that links the appearance of Ὁ ὬΝ to the Palamite controversies of the mid-14th century. Titos Papamastorakis, in speaking of the image 28 in a chapter of his work, “Our Lady Brephokatousa,” says this: “The inscription Ὁ ὬΝ (He who is) on the halo of Christ is typical of depictions of Him in the 14th century and particularly after the middle of the century, when the Hesychast movement was officially accepted by the Orthodox Church.[15]” It would be interesting to hear the reasoning that brought this author to suggest a link between Hesychast theology and the Ὁ ὬΝ .

The question of the origin of the Ὁ ὬΝ in the image of Christ deserves more study, which we hope to do at a later date. Much depends on dating the images because an image with Ὁ ὬΝ, when taken in isolation, could result from a later modification. What remains certain, no matter the origin of Ὁ ὬΝ in time or in geographic space, is how it is too heavy with theological meaning, especially when inscribed in Christ’s halo, not to confirm the fundamental affirmation of this study: Christian images of the first millennium, and those produced by the Eastern half of Christendom in the second, are highly theological.

—————————————-

Bibliography HO ÔN

Anguélov, Dimitre, Le bogomilisme en Bulgarie, Toulouse, Édouard Privat, Éditeur, 1972.

“Bogomils,” The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium I, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1991, p. 301.

Cosmas le prêtre, Le traité contre les bogomiles, Henri-Charles Buech et André Vaillant, trs., Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1945.

——-, Les Balkans au Moyen Age : la Bulgarie des Bogomiles aux Turcs, London, Variorum Reprints, 1978.

Goldfrank, David M., “Burn, Baby, Burn: Popular Culture and Heresy in Late Medieval Russia,” The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 31, no. 4, 1998, pp.17-32.

Ivanov, Jordan, Livres et légendes bogomiles :aux sources du catharisme, Monette Ribeyrol, tr., Paris, G.-P. Maisonneuve et Larose, 1976.

Klibanov, A., “Les mouvements hérétiques en Russie du XIIIe au XVIe siècle,” Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique, vol. 3, nos. 3-4, 1962, pp. 673-684.

Obolensky, Dimitri, The Bogomils : A Study in Balkan Neo-Manichaeism, Twickenham UK, Anthony C. Hall, 1972.

Sanidopoulos, John, The Rise of Bogomilism and Its Penetration into Constantinople, Rollinsford, NH, USA, Orthodox Research Institute, 2011.

—————————————-

[1]Tania Velmans et al., Rayonnement de Byzance, Paris, Zodiaque, Desclée de Brouwer, 1999, color plate 53, (p.152), p. 142-144.

[2]Sacho Kornevski, Elizabeth Dimitrova, Macédoine byzantine: Histoire de l’Art macédonien du IXe au XIVe siècle, Éditions Thalia, 2006, pp.212-213.

[3]S.I. Maslenitsyin, Jaroslavian Icon-Painting, Moscow, Iskusstvo Publishers, 1973, p.9-11, plate 6.

[4]Manuel Panselinos, Dimitrios Salpistis et al. (dir)., From the Holy Church of the Protaton, Thessalonika, Hagioritiki Estia, 2003.

[5]Ibid, p. 58-59 and 301.

[6]V.N. Lazarev, Icônes Russes: XIe-XVIe siècles, Paris, Desclée de Brower, 1996, plate 17, p.158.

[7]Ibid, plate 88, p.253.

[8]M.V. Alpatov, Frescoes of the Church of the Assumption at Volotovo Polye, Moscow, Iskusstvo, Publishers, 1977, plate 53 et al.

[9]Rayonnement, plate 256, p.303-304.

[10]Maleri Sergueïev, Roublev, Paris, Desclée de Brouwer, 1994, plate 25, p. 185.

[11]Ibid, plate 17, p.128

[12]V.N. Lazarev, Icônes Russes: XIe-XVIe siècles, p. 292, plate 102.

[13]Valeri Sergueïev, Roublev, plate 40, p.238.

[14]I would like to thank M.John Barns, Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, for the suggestion that led me unto the trail that supports my hypothesis of “why.”

[15]Titos Papamastorakis, “Icons 13th-16th Century,” in Icons of the Holy Monastery of Pantocrator, Mastorakis.

The Greek Ο ΩΝ is not translating the Hebrew “YHWH” but rather the phrase “ɂehyeh ɂašer ɂehye” meaning something like “I am what I am.” Also, YHWH or /yahweh/ is not a present participle in any vocalization. At best it is a 3rd masculine singular verb of the imperfect or “prefix conjugation” in the causative (hiphil) stem. Other etymmologies have been given for non-Hebraic roots, yet regardless of the origin of the name, the Israelites interpreted the hame YHWH as meaning “ɂehyeh ɂašer ɂehye.”

Thank you for fascinating article

The N, If originated in Russia, may be an “i”, not an N and sounding like a long ee…?

Great question!

I think the earlier writing in the halo was “A-W” the Alpha and Omega as seen in the Catacomb of Commodilla mid 4th century. And in the east at least there was almost always a cross bar in the halo. . . .

Have you looked at early Christian coins and Manuscripts for this question?

Thanks for the topic!

I think it would be of interest to also compare icons, manuscripts and coins with the liturgical traditions of other Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Churches which include in the nimbus of Christ, and the theopaschite image of the Cross the same meaning of the Greek letters but in their own letters/language.