Similar Posts

Sacred and Secular Art in Light of Tradition

Part 1

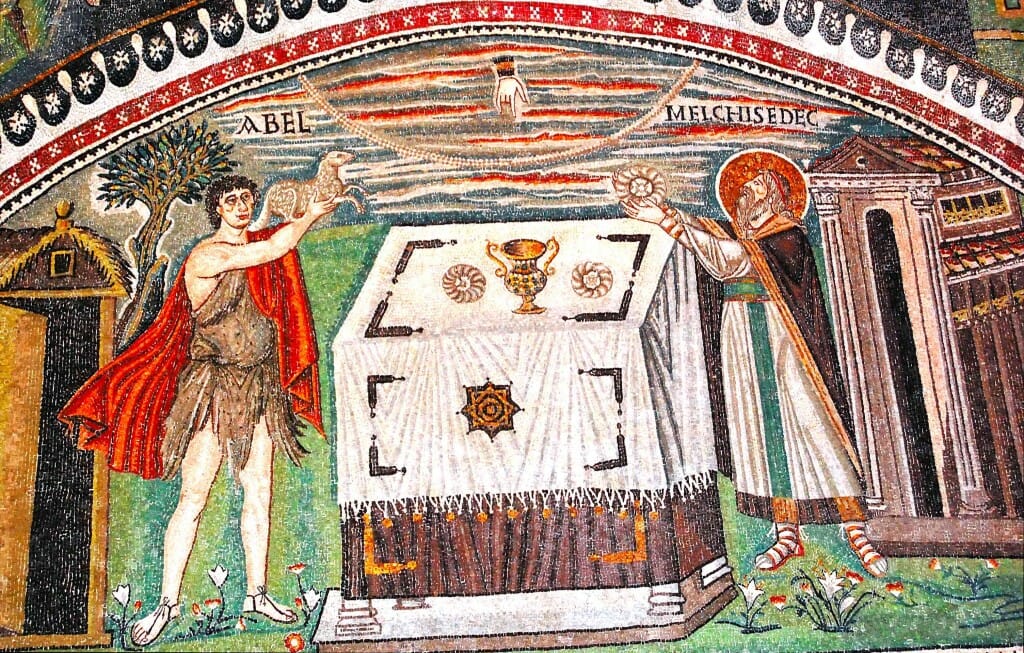

Abel and Melchizedek bringing their offerings to the altar. Basilica of St. Vitale, Ravenna, 538-545 AD.

If the gift of art is not returned to the One from which it came, thereby no longer binding us to Him, it will cease to bring consolation, liberation, and blessedness.

“For of Him and through Him and to Him are all things…” – Romans 11:36

Art is a divine gift to man, an illumination, “Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, and comes down from the Father of lights…”(Jam. 1:17) Therefore, it reaches its loftiest heights when it becomes once again a gift, an offering, a sacrifice of praise, a doxology, returned back to God as Eucharist. We see the divine image in man not only in his nous, speech, free will and capacity to love, but also in his works of craftsmanship. For the Archetype of man is the Divine Craftsman, the Logos, “by whom all things were made.” Hence, as craftsman, man fulfils his vocation using his gift liturgically, that is, by working in cooperation with divine energy, ordering, and shaping his soul in virtue harmoniously, thereby depicting within himself the divine likeness. This likeness is our reintegration in the Good, grounding in the Truth and participation in uncreated Beauty- the partaking of divine nature. Thus, man becomes a living icon mediating the divine Presence. In the icon we find the convergence of life and art as ultimately sacramental creative activities. Indeed, the highest function of art is to mediate between the Divine and human, to give access to the Divine in the realm of culture. Art then, as attested to by all major world civilizations, is essentially inextricably related to religion (religiō) – which etymologically can be said to mean to bind fast to the Sacred – hence, to an act of liturgical worship, to cult. It is often overlooked that cult-ure arises from cult, even secular man has his rituals, shrines, relics and “icons.” So we begin to know the underpinnings, the worldview and devotion of a civilization, by discerning the forms of its art. “…By their fruits you shall know them.”(Matt 7:20)

As Orthodox Christians we tend to live in two spheres at the same time, and more often in between them. We might hold traditional perspectives in some respects, but use secular standards in others. At times we even rely on secular presuppositions to judge Tradition, without realizing it. We tend to suffer from a lot of these cultural blind spots. This, I think, is most apparent when it comes to the question of “art.” For the iconographer things tend to be a bit black and white, at least most of the time. Isolated from contemporary developments in the realm of non-liturgical art he guards his spiritual integrity. But for those who don’t have a calling to engage in liturgical art, such an insular attitude is not enough. What are they to do? How are they, as Orthodox Christians, to approach their practice as artists? And, what about those who have not become part of the Church? What are we to make of their work? Is non-liturgical art capable of conveying intimations of the Sacred? Hard questions, to say the least, but ones worth asking, although the answers might not be so readily available at the moment.

Virgin and Child, catacomb painting. Rome, 4th century.

Here we see one of the earliest examples of what would become the Mother of God of the Sign or the Platytera types.

Tradition, Temperament & Culture

Perhaps we can begin answering these questions by calling to mind the catacombs of Rome. As the Church suffered under the great persecutions its artists simultaneously experimented with vitality, frescoing their secret places of worship in varied and unusual ways. These Christian artists took forms readily available to them from their Greco-Roman culture and with creative dexterity reshaped them, in a manner that would later impact the development of the pictorial language of the icon. Hence, Church culture baptized existing visual forms, distilling from them that which was in accord, and useful in communicating, the new life in Christ. Initiation into this new life is the entering into and participating in the mystery of Tradition, often referred to as, “the life of the Holy Spirit in the Church.” Tradition also entails the “handing down” of the revelation, the “mystery hidden before the ages,” that is, the Incarnation of the Logos, through whom we become partakers of the divine nature. In short, ecclesial art can be said to have “revalorized” contemporary modes of expression, thereby making them efficient conveyors manifesting Tradition.

It goes without saying that things are a bit different now. Some might contend that the Church is no longer in its “primitive” stage and consequently not as flexible in its interaction with immediate culture. As it is often emphasized, the pictorial language, and other aspects of the Church’s liturgical art, has reached a level of maturity, clarity, of crystallization needing no arbitrary and willful revision. This is very true in many ways. Yet, we should also bear in mind, and it is hard to deny, that iconographers throughout history in creating a “…integrated and complete painting system based upon the ground of the Hellenic cultural tradition and its trends…never abandoned the dialogue with other artistic and cultural traditions. Therefore, many elements and artistic solutions were borrowed by the icon painters in order for their work to be always in a process of renovation becoming more functional and fresh…icon painting in the past was always alive and in a natural progress and enlargement of its body.”[ii]

In making this point we are not just welcoming and excusing an “innovationist” spirit. Rather, what we are saying is that Tradition cannot be trapped into just one approach or mode of expression, no style or school can claim monopoly to the “most authentic” formula, although it might be firmly grounded on, what can called, the “timeless” pictorial principles of iconography. Moreover, these principles are not to be taken as purely static, but rather as extremely flexible and expandable. Also, we should remember that these are not the Tradition itself, but that which makes up its glorious garment, the efficient grammar and letters of a language, giving clear expression and manifesting the unfathomable depths of Tradition.[iii] The principles derive their timelessness and accuracy from participation in immutable Tradition.[iv] From this participation they become the unifying components in the diversity of styles. The styles can perhaps be called the “unique modes of receiving” Tradition.[v] So iconographers of ages past have not been as insular in their practice as we might like to think and as some expect them to be today. In the course of history Tradition has found expression in a variety of personal and cultural temperaments, as iconographers have creatively confronted and resolved immediate needs. This, among other factors, clearly shows the Church as truly the living Body of Christ, composed of different members, each with unique functions and gifts, contributing to the edification of the whole organism.[vi] This, of course, happens organically, not for the sake of individualist “self-expression,” or mere novelty. In short, there is room for dynamic creativity in cooperation with the Holy Spirit. Obedience to Tradition does not stifle or deaden, but paradoxically transforms, purifies and resurrects, persons and cultures to the fullness of their potentials. Hence, with this in mind, Ouspensky would encourage his western students not to limit themselves by superficially copying the Russian style, but to also look at their cultural forebears, such as the Romanesque masters, for pictorial possibilities closer to their unique temperament.[vii]

St. Mark, from a Gospel Book produced at Corbie. Bibliotheque Munuicipale, Amiens. 1050 AD.

Here we see the subordination of volume and naturalism to flat color fields,linear rhythm, abstraction and ornament. To some this work might appear to be “cartoonish.” But, we should bear in mind that, before “cartoons” in the modern sense ever came around, the medieval craftsmen exploited abstract form in order to emphasize the supra-sensual, noetic content of their works.

The Catacomb painters were surrounded and imbued by the Hellenic artistic heritage, but today we have a plethora of artistic models via the internet, instantly made accessible through an image search by the mere push of a button. The many schools of iconography, and art running the course of many centuries and cultures, can be viewed simultaneously as we scroll down our computer screens. Who can deny the positive sides of this information technology? What iconographer nowadays has not availed himself of this vast resource? We have also seen in the 20th century major developments in the history of painting. In particular its reassessment of naturalism, exploration of “primitive” art and abstraction, which in some respects parallels and affirms the pictorial language of the icon. Even the sacred art of non-Orthodox cultures can be studied more readily, as we consider pictorial problems in iconography. Some iconographers would even argue that the breakthroughs of 20th century painting, and elements of contemporary secular art, can be revalorized, put to the service of the icon.[viii] Others might prefer to find inspiration and clues in the parallels found between the sacred art of the East and the icon. However, these two alternatives are not necessarily mutually exclusive, an iconographer can perhaps embrace both possibilities. The visual culture of our contemporary world is larger than it has ever been. It seems to me hard to deny that these factors will have some degree of impact on contemporary iconography, but only time will tell. Things are not so neatly compartmentalized along cultural lines anymore in the “global village” of our postmodern world. So an insular attitude towards iconography seems to be insufficient, if not a stifling denial, within our current predicament.

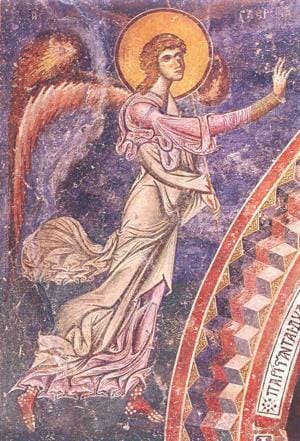

Archangel Gabriel from the scene of the Annunciation. Sr George church, Kurbinovo, 1191 AD.

This fresco is a good example of the the two pictorial approaches seen above, the Greco-Roman naturalism and Romanesque abstraction. This style, in its exuberant rhythm, can be referred to as “mannerist,” and this is not to be taken as a negative epithet.

It is unquestionable that various national cultural temperaments have left their mark in the life of the Church. These are to be rightly cherished as contributing to the richness of the Orthodox liturgical experience. It is then worth looking at the question of culture from another angle, which brings us back to the catacombs. For the Church creative engagement with contemporary culture did not just end at the catacombs. Rather, it would eventually transform the entire Roman Empire. Maybe we should pause for a moment and consider whether or not we are taking things for granted as we isolate ourselves within an ecclesial ghetto, forgetting that Church culture can still have major impact and shed some light on the state of the civilization surrounding us, particularly the state of contemporary art. Some might resist dialogue with the contemporary art community, but in doing so are they just breeding a fundamentalism that deprives both the liturgical and non-liturgical artist of unexpected revitalization, positive convergence and cross-fertilization? And believe me, by raising these concerns we are not here opening the doors of the Orthodox Church to the modernist trends that the Roman Catholics have suffered from for many centuries now, but that became rampant after Vatican II. We are definitely not advocating liturgical reforms or the creation of “modern” icons! Yet, in resisting arbitrary novelty or modernism in iconography we should be wary of the other extreme, a static and ossifying formalism in liturgical art, which is another way of taking the letter for the spirit of Tradition.

Annunciation, by George Kordis. Contemporary icon.

Here we see an icon which at first glance might appear to be “untraditional,” but, in fact, is in accord with the “mannerist” example we’ve shown above.

Yes,Tradition stands above contingencies and not to be thought of as bound to historic determinism. However, it continually generates new forms of ecclesial art, as it accepts and revalorizes useful aspects of the surrounding culture, albeit in slow increments and subtle ways, perhaps indiscernible at the given moment. But creative participation in this dynamic, as we have said, always presupposes obedience to the mind of the Church, an obedience which is paradoxically liberating. This creativity does not demand from us to first become saints, in order to then theologize in color. No, we first make choices in humble submission to Tradition, to the best of our capability, then the Church tests and decides on their efficacy. I doubt St. Rublev considered himself a saint when he decided to edit the composition of the Hospitality of Abraham to its bare essentials, in order to articulate theological nuances previously overlooked. Yet, he saw beyond the letter and dared to depict what he apprehended of the living Tradition with his noetic eyes. He saw the prototype, not as the outward form given to him to be reproduced, but as the inner meaning, the logos, contained in the composition.

St. Paul’s Vision on the Road to Damascus, by George Kordis. Contemporary icon.

In this icon can be seen the confluence of traditional pictorial forms, along with the revalorization of 20th century painting. That is, we see some aspects of the Byzantine style and Romanesque “mannerism,” along with the use of flat and broad fields of color reminiscent of Van Gogh and 20th century abstraction. All of this tends to have a sense of “expressionist” vigor, wish clearly conveys the sense of dynamic and transformative encounter of the sacred event.

How lifeless it would be for the Church, if we were all to sit around and wait for some kind of authorization, as to the legitimacy of our sanctity, before we did anything creative in our work. So we act in spite of our weaknesses, as we struggle towards deification, offering the gift of art back to God. Hence, those who try to make a contribution in this creative effort, as they serve the Church to the best of their capabilities, should not be hastily condemned or dismissed if their articulation seems to be for the moment imprecise and obscure, seemingly untraditional. We must be patient. The Church will decide in its own time. In the end, what enters into the milieu of liturgical art is vetted by the Body through the grace of the Holy Spirit. That which is not conducive to its edification and is pastorally harmful, not in harmony with Tradition, inevitably falls to the side as dross. That which remains is the purified gold that adorns the glorious garment of Tradition.

To be continued…

________________________________________________________________

Notes:

[i]This article is an expanded and revised version of On the Gift of Art, which responded to the exhibition” Gifts” (December 2013 – January 2014), State Museum of Architecture, Moscow. See http://sacredmurals.com/texts/on_the_gift_of_art.htm

[ii] This passage forms part of the statement of purpose of the IKONA group, mainly composed by iconography professors in European universities, their leader is Dr. George Kordis, Faculty of Theology, University of Athens. Their aim is to counter the static repetition of old models in iconography. Their statement further says, “Today unfortunately the art of icon painting in all Orthodox countries seems to be static and engaged in an uncreative repetition of its glorious past. Old masterpieces are reproduced again and again and the art of icon painting looks unable to continue the real tradition of the Church and its attitude against the different painting modes of the world.” For the full statement see: http://eikona.org/

[iii]Titus Burckhardt explains, “Granted that spirituality in itself is independent of forms, this in no way implies that it can be expressed and transmitted by any and every sort of form. Through its qualitative essence form has a place in the sensible order analogous to that of truth in the intellectual order; this is the significance of the Greek notion of eidos. Just as a mental form such as a dogma or doctrine can be the adequate, albeit limited, reflection of a Divine Truth, so can a sensible form retrace a truth or a reality which transcends both the plane of sensible forms and the plane of thought.” A point to notice here is the notion of “adequate, albeit limited, reflection of a Divine Truth” (emphasis added). Titus Burckhardt, Sacred Art in East and West: Principles and Methods, Perennial Books LTD., Middlesex, U.K. 1986, pp. 7-8.

[iv]As V. Lossky says, “The dynamism of Tradition allows no inertia either in the habitual forms of piety or in the dogmatic expressions that are repeated mechanically like magic recipes of Truth, guaranteed by the authority of the Church. To preserve the ‘dogmatic tradition’ does not mean to be attached to doctrinal formulas: to be within Tradition is to keep the living Truth in the Light of the Holy Spirit; or rather, it is to be kept in the Truth by the vivifying power of Tradition. But this power, like all that comes from the Spirit, preserves by a ceaseless renewing.”As quoted by C.A. Tsakiridou in Icons in Time, Persons in Eternity: Orthodox Theology and the Aesthetics of the Christian Image, Ashgate Publishing LTD, Surrey, U.K. p. 65.

[v]Tsakiridou, Ibid., p. 64.

[vi]Lossky also notes, “The pure notion of Tradition can then be defined by saying that it is the life of the Holy Spirit in the Church, communicating to each member of the Body of Christ the faculty of hearing, of receiving, of knowing the Truth in the Light which belongs to it, and not according to the natural light of human reason.” Ibid.

[vii]Chantal Savinkoff, “Une leçon d’iconographie avec Léonide Ouspensky: Extraits d’un entreitien avec Chantal Savinkoff,” Paris, February 1974. In The Orthodox Messenger, Special Issue, “Life of the icon in the West,” No 92, 1983. Our translation from the French text. http://www.pagesorthodoxes.net/eikona/iconographie-ouspensky.htm

[viii]The IKONA group is a case in point. On this regard their statement reads, “The IKONA group… attempts to give a motive for an interchange with contemporary art, tracing the possibility of adopting elements from secular art. The main goal is not the creation of modern icons outside the tradition of the Church, or the replacement of the old mode. The continuity and the enrichment of the tradition is what is intentionally pursued by the members of the Group IKONA.” http://eikona.org/, op. cit., n.2.

[…] On the Gift of Art…But What Art? – Orthodox Arts Journal […]

Great article! Looking forward to the next installment.

Thank you so much for this wonderful article, Fr. Silouan. I think many of us can identify with your thoughts and are trying to lovingly approach Tradition with living breath and open eyes. You know very well how I myself are attempting certain things in my icons. But those of us who are aware of the history of the Orthodox Arts are simultaneously hesitant and cautious. Our caution is due to the fact that that the icon and other traditional forms where all but lost only 100 years a go, and it is truly only in the last generation that we have seen a visible recovery of this art. It has come forth as a wonderful explosion of energy in the rediscovery of the ancient forms and their spiritual depth. This recovery has been mostly conservative, conservative in the now very acute awareness of the historical process by which the slip happened. So when we look back starting even in the 16th century (just as in the Catholic Church really) we see the seeds of decadence, not so much in a “naturalistic” style at first, but in the increasingly fanciful images born from the imagination of Russian iconographers. Although the recovery of traditional forms has started, it is not yet complete, and many Orthodox churches are still decorated with images and approaches that are dubious. So when I feel myself or see other contemporary iconographers being too overly concerned with modern ideas, I hesitate and at least wish we would all remove our sandals before going forth, for this is a hallowed ground.

Indeed, caution is always wise, Jonathan. I agree wholeheartedly on the need of reverence towards Tradition and humility in approach. So there will always be a need to vet our ideas and work not only in light of our predecessors in the Tradition, the great masters and schools of the pre-decadent period, but also among our fellow iconographers, who have a balanced theological, artistic, educated and reverential approach. In other words, we can not fall into the danger of isolation in the creative act. If we don’t have a community to run our ideas by, to challenge and test us, in a spirit of Christian love, in friendly and respectful comradery, we will loose perspective and take our fanciful interpretations to be “illuminations.” In other words, we will confuse the psychic with the noetic.

The icon is not only a support of private contemplation or prayer, but is also communal, and hence, pastoral and didactic; a catechism into the mysteries of the Faith. A catechism is a mystagogy, not a mystification. The one makes clear, the other obscures. What can be pictorially reasonable, understood and according to Tradition, within the private conversation of an initiated few, might in fact be detrimental for most of the faithful. So there must be caution about a pictorial language that, rather than helping to elucidate the mystery, leads to confusion. Yes, this would be reminiscent, as you allude, to the kind of problem that became acute around the 17th century, with the introduction of overtly “allegorical” tendencies in compositions. Some of these compositions became so indecipherable that pamphlets had to be published as aids in decoding their meaning.

Yet, in being overcautious about this problem, we should not take the extreme attitude of decrying anything that is symbolic in an icon, or even “allegorical” to some degree. It is a matter of how central a role the allegory has in a composition, and whether or not a concept usurps the veneration of a person. Since, it goes without saying, we venerate persons, not ideas. Nevertheless, Symbolism does have a place in the icon and functions in many levels, not just one. The icon is both, and I stress again, both symbolic and historical. It depicts persons and articulates theological ideas. When speaking of a symbol, we should remember that it is not to be identified solely, and merely, with the idea of a “sign,” or a “non-reality.” As we have heard many times, the symbol participates in the reality it re-presents. Anyhow, it is all a matter of not going to either extreme, of keeping a healthy balance and tension, so we don not fall into historicism, in seeing the icon as solely a “historical portrait”, nor the obscurantism of excessive “allegory.”

The issues surrounding the period of “decadence” are important to study and reconsider. As you mentioned, it is not just a matter of “naturalism” but also of the dangers of the “imagination.” And I guess this is where, for me, the issue lies, what are we to make of the “imagination.” Unfortunately, most of the time, this term is used to denote a negative use of our capacity to form mental images. Hence the usual association of the imagination with irrationality and the demonic. On the other hand, there is the Romantic adherence to it as the primary and most reliable vehicle of creative inspiration. This romanticism is obviously not in accord with Tradition. Nevertheless, all of us who engage in the creative act of iconography, if we are not merely making mechanical copies, will be editing, considering options, meditating on, and bringing together, from the archive of our image memory, possibilities to solve pictorial problems. In my opinion, the imaginative faculty is an undeniable part of the creative act, so it is not to be taken as an inherently negative process. But, the nous should always be the guide of the process, guiding according to the principles of Tradition, thereby keeping the imagination cautiously guarded from fanciful tangents in interpretation. So yes, caution, reverence, and the warding off of isolation, through a healthy vetting process, is very important.

I can refer to you, priest Silouan Justiniano, as there are many things in your views which I can agree, but there are many I can’t agree with. I will focus on those in which I’m disagree. It is important to be considered carefully because a huge influence on the icons.

Your essay is a complex mix of theological truths and intellectual elements that at least deserves a serious debate before being accepted as truth. In one and the same sentence you claim candid theological truth, but which you immediately supported with dubious statement. This is not so difficult for text analysis, but is mislead for readers.

1. Dear priest Justiniano, there is something, which I also find important – you did not finished your first quote: “Every good act and every perfect gift comes from above, descending from the Father of lights …” (Epistle of St. James the Apostle. 1: 17). Continuation of the quote is very important and is indicative of the further development of your thoughts. I will supplement the quote, otherwise without it, the quote would be not complete, and your thoughts will not find a suitable explanation: “…with Whom is no variableness, neither shadow of turning”. This is very important because the quote describes the essence of God, with Whom there is no change, there is no shadow of turning! That’s according to the Epistle of the Apostle Paul. Cutting the quote seemed suspicious to me at first, but after reading your article, my suspicion was confirmed, and now I will explain how this happened.

2. I think there are no icon painters who do not have the “calling to engage in liturgical art”, as you are expressed. If there are such icon-painters, they can not be icon-painters at all and can not be Orthodox as well. So for us there is no issue at all what to do with such people. They simply have no place in Orthodoxy. This is not a matter of extreme, nor a question of fundamentalism too. This is a matter of Tradition.

3. You ask whether non-liturgical art is able to forward the suggestions of the Sacred. For different civilization`s religions it is probably possible. But in terms of Orthodoxy there is no chance of this to happening. There’s just no non-liturgical art in Orthodoxy. If we have non-liturgical art, therefore it is no icon. There is non-icon. Non-liturgical art is not iconic. It is simply.

4. You speak at the beginning of art in the catacombs in Rome as prefigure of icon, inspired by Greco-Roman art. You should know that very few ingredients from depicting language of art from Roman catacombs survived in icon. In the base of the language of icon actually is lying a visual system that can be observed almost fully developed in the synagogue at Syrian city of Dura Europos, in which is preserved paintings from the mid-third century. Pictorial language developed in the Roman catacombs almost completely disappeared afterwards, because, as you rightly pointed out, it is inspired by Greco-Roman art, which is pagan in fact. Leonid Ouspensky conscientiously supports exactly this spirit, stating that “the forerunner of the Church is not a pagan world but ancient Israel”.

5. Scarcely there is a icon-painter or iconographer who feel “isolated within the church ghetto”. This is very strange conclusion. Equating the Church to ghetto is not a good comparison. On the contrary, precisely this “isolation” means the complete dedication and fullness of life within the Church of Christ. Yes, we all live secular life too, but it is not and should not be reflected on the sacred iconography. As it is not reflected in the Orthodox liturgy too.

6. The Orthodox liturgy, the life within the Church is not fundamentalism, but a necessity. If any non-liturgical artist wants to communicate with the liturgical icon, should adopt the language of the icon as it is in essence, and as it always is there for millennia. Connection can be made only at this point, not beyond it.

7. I dare to say that tradition is not “continually generates new forms of ecclesial art, as it accepts and revalorizes useful aspects of the surrounding culture”. Moreover – fortunately Tradition has little to do with the surrounding culture. It exists solely within the Church of Christ. Traditions that appear, disappear and established outside the Church can engage us, as far as we are living in secular environment, but we should not allow this environment to enter within the Church. Nor secular or any other tradition can be randomly mixed with the Tradition of the Church.

8. Yes, icon “depicts persons”, but not of individuals in their earthly life, which is the secular portrait, but in their hypostasis – their eternal life. In this connection, the icon has no connection with secular art. Secular art makes portraits, Orthodox painting makes icons.

9. I agree that “icon painting in the past was always alive”. But it is just as alive today, without mixing with secular art. It is eternally alive at all times, because it has many ingredients that protect us from fruitless copying. Never in the past icons were not just copy from each other, like a modern copy machines. Icon-painters of all time have never been served as xerox machines. Always they changed the nonessential elements in the composition, without leaving the liturgical language of icon. Thus they have kept alive the language of icon and so each icon recreates the living language of the Church. I can list which are the ingredients that always have been completely changed in the icon. I have explored a huge amount of authentic Byzantine works of (common Christian) painting from 2nd to 15th century – from all genres and all geographic areas of distribution.

10. You talk a lot about isolation of the creative act of the iconographer. I do not understand about what insulation is the question. Every true icon-painter creates an icon only by custom. Orders can only come from the people who are members of the Church. Because icons can serve only for liturgical purposes. Icons make no sense as secular works of art. So I do not see how an icon-painter can be isolated from the Church, making the icons in the spirit of Tradition, which meet the liturgical needs of the Church. It is this Tradition gives us the way, by which must be made icons. And thus the mode is there unchanged for millennia. This method has become known in the nineteenth century as a Byzantine painting and thus is inculcated in modern times. And while this sacred formula exists unchanged, there is no danger of “confuse the psychic with the noetic”.

But here obviously you had in mind the isolation of the iconographer from secular life. I think this isolation is completely natural and highly respected in the spirit of Tradition. An icon painter cannot make icons if he does not live his life within the Church.

11. I think that you contradict yourself when you say that “we are not here opening the doors of the Orthodox Church to the modernist trends”, while the “icon” of Prof. Dr. George Kordis, the Vision of St. Paul on the road to Damascus “reminiscent of Van Gogh and 20th century abstraction” for you. Is really to you, and to Prof. Dr. George Kordis also, Van Gogh and abstraction artistic movement of the twentieth century are not modernist trends? Art history clearly shows that they are just secular modernist trends. And you insist Church to be open to them? I cannot agree with such action! And I’m not the only one.

12. Yes, Prof. Dr. George Kordis is a very good master. The difference between his works on religious themes and true iconography at first glance is not large, and the inexperienced person would not notice a significant difference, but in practice it is huge. As my friend icon-painter Marian noticed, when he see a work of Prof. Dr. George Kordis that blends secular and sacred elements, he says: “A, Kordis!” And when he see the icon, which was built only from sacred elements, he says: “A, an icon”.

Do you think, dear priest Silouan Justiniano, that in the face of pictorial Tradition continuing nearly 2000 years, we have right of those mixes of non-sacred ingredients and of such intellectual fluctuations? I`m convinced precisely that the “static and ossifying formalism in liturgical art”, as you call it, actually is alive Tradition of the Christian liturgical painting that protects unchanged the language of iconography through the millennia. If in modern Orthodox iconography there is some formalism, in any case it will not be removed by mixed it with elements of secular art.

With best and hearty wishes,

Alexander Stoykov

I understand your desire to protect that which is sacred, it is a good instinct and is to be commended. But There are many things in your comments which are problematical. They are problematical for two main reasons. The first thing which is problematic is that you confuse the two aspects of how Christ participates and manifests himself in the Church through the Holy Spirit. You confuse that which comes from above and that which comes from below. You seem to want those two things to be the same. All of what Christ does is a manifestation of how what comes from Heaven is united to that which is “lost” on Earth.

From Christ choosing fishermen and tax collectors as disciples, associating with prostitutes and samaritans, to his healing sick and impure people (think of the woman who was bleeding, the leprous, the demon possessed, all of these would have made Christ impure in the Law), to his resurrecting the dead, to his own crucifixion as a criminal, to his descent in to the pit. Everything Christ does is a transformation of that which is sinful and lost and “secular” into vessels of his glory. As St-Paul said to the former pagans Colossians: “And you who were once strangers and enemies in mind, doing evil deeds, he has reconciled in his fleshy body so as to present you holy and blameless and irreproachable before him.” And so if the Ethiopian Eunuch (remember a eunuch was an impure outcast in Israel) was baptized into the Church, became a member of Christ’s Body, why does it bother you that cultures, architecture, style and images can also be baptized and become vessels for Christ’s glory? Are we saying that paganism, secularism, modernism etc. can become a source for sacred art? Of course not! No more than tax collectors, prostitutes, pagans and criminals can become a source of the Church! But can those people become the “body” of the Church once they are transformed through baptism by the True source which is Christ? Of course! In fact there is no other way for the Church to be constituted, and so the same goes for music and art and poetry etc. Does it bother you that Orthodox hymnography is often written using the grammar, the style and meter of Homer and other Greek poets? Does it bother you that domed architecture had no precedent in Israel, nor the basilica, the apse and other aspects of Church architecture, but were Roman in origin? Do you see where I am going?

This brings me to the other problematic aspect of your comment, which is that it is factually inaccurate. So many aspects of Christian art took their forms, their “bodies” from Roman culture that I could scarcely enumerate them. I will just chose one for economy of space. The Halo. The halo was used by Romans and other cultures to denote glory and was found before Christianity for gods and Emperors. So the very symbol of sanctity in our Church, that which shows a saint’s glory is taken from pagan art. Look at the Doura Europos synagogue again, and if you are blind enough to ignore that Moses is dressed like a Roman Senator (like Christ and his Disciples will be until today in icons), you will not miss that fact that no one has a halo. So not only do you miss the entire point of who Christ is and what Christ came to do through your confusion of Spirit and Body, but anybody with even a hint of knowledge of how early Christian art came about will see that your claims have no basis and are simply an attempt to fit icons and the liturgical art of our Church into your ideological categories.

And so finally let us come to your very first criticism, which is how fr. Silouan does not finish his quote from St-James Epistle. Please notice, that in this missing quote it is God who has “no variableness, neither shadow of turning”, not the “every good act and perfect gift”, those gifts are innumerable and in endless variation just as God’s Creation is manifested in multiplicity so too we find multiplicity in the colors, techniques and even typology of icons. Does this mean that anything goes, that we can have rock’n’roll liturgy and cubist icons? Of course not! But it does mean that we must look at the world through the lens of Tradition and the breath of the Holy Spirit and not turn a blind eye to those aspects of the fallen world which can become vehicles of Christ’s Glory, just as the Romans, the Armenians, the Ethiopians, the Copts, the Syrians, the Irish and so many others did in the very early centuries of Christianity.

Dear Jonathan, I`m guess you are calling to me, so I will take the initiative to answer you properly. But I will not use this insulting vocabulary that you used. Because I not see any reason for anger. I ask you let the anger away, and I hope in your objectively perception of text.

1. The first and most important thing that I will notice in your comment, is that in Christ there has no two or three or more aspects in sense that you used. There is only one aspect because He is God, He is “Alpha and Omega” (Revelation of St. John the Theologian, 1:8), He is all, “Who is and Who was and Who is to come” (Revelation of St. John the Theologian, 1:4, 8. In this sense, all in the world is merged and unitary in consubstantiality with the Father. Here I would like to ask you where you did saw that I see different aspects of Christ? Give me the exact passage. If I made a mistake, I will apologize you.

2. Second most important thing you should know is that icons had never had been consecrated. Such of ritual occurred only in Russia after 17th century. Never such of ritual was practiced earlier, because the icons are lit by itself. And they are holy by itself, because they originate from the Holy Ubrus, Acheiropoietos – the Unworldly, Non-made-by-hands Image made by Christ Himself. In this sense, icons contain the most important sacral language which we can know. This is the sacred language comes from God. Just in this sense I mentioned a second part of the quotation from the Apostle James, missed by priest Silouan. Here I’m not talking about acts, healing and miracles of Christ, I’m not talking about how He is dressed and what gestures do. I’m talking just about substantial language, rather than what is delivered by the language. You confused what was pronounced by the language with the language itself, with its structure. This is a mistake in your understanding.

This language has been cleared of numerous Church Councils to the 9th century, when it was finally determined, after the terrible period of iconoclasm in Byzantium during the 8-9th century. Specification of the language is celebrated today by the Orthodox Church as Feast of Orthodoxy or Sunday of Orthodoxy. That’s not my view or “ideological category” but opinion approved by Sixth Ecumenical Council and confirmed by Seventh Ecumenical Council. No ingredients can be accepted in this language, if it not is approved by the Church Council. Not a mortal man has the right and power to import any changes in the structure of this sacred language. This can be done only by the Church Council, the Ecumenical Council. Because precise this language makes icons sacred itself. Neither gestures, nor clothes, nor other external ingredients.

In this sense, any ingredient of an external “culture, architecture, style and images” no “can be baptized and become vessels of Christ’s glory”, if it was not specified by Ecumenical Council of the whole Church of Christ. No mortal man has such rights itself. Therefore what makes prof. George Kordis is dangerous and will have bad consequences. Because it violates the approved language of icons and sacred images for the tastes of some people who are not the Church Council themselves.

3. My statement did not is “attempt to fit the icons and liturgical art” because the icons ARE the “liturgical art” itself. Outside “liturgical art” has no icons and no icons are outside the “liturgical art”. They are one and the same thing. You can not make a distinction between icons and “liturgical art”. If you see a difference between, then I would like you to point it out and determine what the icons are and what the “liturgical art” is.

4. I’m will not talking about knowledge of early Christian art. I already explained that, Jonathan, you meant what was said through language, you meant not the structure of the language of sacred images itself. It is clearer that is your misunderstanding. You need to discern between the structure of language, its lexica and grammar, and spoken by the same language. The difference is huge. In fact, it cannot even be compared.

5. I know images of Dura Europos synagogue very well I think. That Moses and any person depicted in the synagogue, has no nimbus is completely understandable. I guess you also know very well that the Old Testament foretells Christ as the Messiah, but did not recognize Him as Messiah. So in case you’re right in that remark and I accept it, but in another sense, which you obviously do not put in your reasoning. But I will say again that in Dura Europos synagogue we can see fully developed the structural system of Christian painting, as it is applied later in each icon and in every sacred Christian image.

6. No doubt I pointed out the missing quote from the message of James the Apostle – not only because he speaks about the essence of God, and that is more important, because what he said with tremendous power refers to the language of icons, that keeps the essence of God. The icons are the only images that preserve and recreate the essences of God – hypostatic life. Jonathan, this should be clear for you very much, if you do with icons. Otherwise there is a risk for you to open for any “rock’n’roll liturgy and cubist icons”. Besides I find the example with Irish for lamentable.

With best and hearty wishes,

Alexander Stoykov

I apologize if you felt I was angry in my response to your comment. I think I am more astounded than angry. This will be my last response to your comments as this is not really the place for such a long and involved discussion. I wonder if there isn’t a barrier of language between us. When you say that in Christ there is only “one aspect because he is God” I don’t quite know how to respond. According to Chalcedonean Christianity, Christ has two natures, a divine and a human nature, and it is precisely within that framework that I had structured my last comment and said that you are confusing Heaven and Earth. I see again in your most recent comment that it seems you are making the same error when you use words like “hypostatic life” to describe icons. When you speak as if the language of icons was somehow completely approved at the 7th ecumenical council, this is impossible to accept. The 7th ecumenical does not in any way mention style of icons nor any specific images or icon types. The only iconological point that can be deduced from the ecumenical council (if we accept the quinisext council as being an extension of the ecumenical councils) is that Christ should be represented as a man and not as a lamb and that we do not represent God the Father in iconography. There are many icon types and elements of iconography which were added at a later date and which we now accept as Orthodox. A few things that come to mind are the HO ON (The W-O-N) in Christ’s crucifix which appears as late as the 13th century, Rublev’s removal of Abraham and Sarah in the icon of the Hospitality of Abraham, the several icon types that are added in later years like the Protection of the Mother of God and many others. Even of those “classic” icons, many of them have no precedent before the 7th ecumenical council and were only developed afterwards, like the Anastasis icon and many of the icons of the life of the Theotokos. In terms of style as well, there is a great variety of style, a huge difference between the style during the Macedonian Emperors or that of the Paleologian Renaissance, not to say anything of the later Novgorod School. For example, how can we not see in the Novgorod School an influence of Scandinavian culture, a far more hieratic and elongated approach than anything found in Greco-Roman Byzantium? To be honest with you, I also share a reluctance in regards to Kordis’ icons, but we cannot oppose such icons simply by stating that there is only one universal and accepted style and type of iconography, that this monolithic style “keeps the essence of God” and that Kordis’ icons should conform to that. If you speak in those terms you will convince no one. We should look at Kordis’ icons and be able to say specifically what the problem is, what makes his icons difficult, what makes us hesitate. Without this, our arguments will have no credibility.

Jonathan, thank you very much for that answer. I`m almost completely agree with you. With some small but important exceptions.

1. Firstly I think that the problems of iconography should be addressed whenever a problem occurs. In this case, there is a problem and the journal reproduces this problem with this article. I think here is the place where the problem must be clarified.

2. I agree with you and actually I see here is a language barrier. But it is not related to the use of English language, but to a mastery of the language of icons. I think that the language of icons is the key to the problem of the whole discussion. You’re talking about style of icons, I’m talking about the language of icons. Between one and other has no connection. You’re talking about the stylistic changes in icons, for thousands of changes in style, genre and stage iconography of icons, which is an indisputable fact and I have no intention to dismiss it because it is so. The problem is there that the changes in styles and scenes of icons are perceived as their sole iconography. But style and stage composition of an icon, in sense – what represents, does not expresses the language of icon, does not explains which are the constructive ingredients that make an icon – icon. What we calling style is actually the stage aspect of iconography – what is depicted. While the language means how the icon is depicted, it constructs the structure of icon, as the spoken language constructs the structure of each sentence. And I call it the language of icon.

The language of icon is related to Rule 82 of Trulo council from 692. This is opinion of Leonid Uspensky, not mine. I’m not expert on councils and I’m fully trusted to Uspensky. The style determines what will be painted in an icon, but the language defines the icon as icon – how it should be painted. If icon is features from any other work of art, it is because the language, not because the style. The structure of language determines what kind of language we use – English, Greek, Chinese, but the style determines what we express through the language. I have explored almost all of Byzantine painting and as there are no different icons in terms of their language structure, I can say that icons are icons because they used only one language – the language of icon. Language defines the icon as icon, not style or scenic details. In a style’s scenic aspect one and the same story can be depicted by icons and by any other artwork. We have depicted all scenes from Christ’s Passions through all kinds of arts. Where is the difference between? The only difference is in the language. What makes the icon – icon, is solely its only language, which is not available and is not used by any other work of art.

Jonathan, the topic is of the most difficult, so I hope you understand me correctly. My whole thesis is devoted to the language of icons. I can give you many examples about structure of language in Orthodox painting, because this language does not applies only to the icons, it also applies to frescoes, mosaics, miniatures, incrustation, reliefs, embroideries. All these works used one and the same language, no matter what they say through it, no matter of style.

For example, all talked only about reverse perspective. But I found that reverse perspective is just one aspect of linguistic diversity in construction of sacred space in Byzantine painting. Along with it also is using axonometry, regular perspective and structures which are fully entered into the flatness of pictorial plane as well. The combination of all these constructions provides a great variety of forms, which can not be tampered and confused with other forms. Moreover, this diversity brings genuine life of Byzantine image, which can not be compared with perspective image.

But reverse construction is the best known, because it is the most commonly used. And it is most commonly used because it has a very high and important theological role. Nor any structure in the space of Byzantine painting was not introduced by accident or by some whim. Every structure has a clear theological role. We know almost nothing about the theological role of these structures, because knowledge about language of Byzantine iconography painting was completely lost and now we have to assemble it as archaeologists – piece by piece.

The reverse construction in Byzantine painting is two kinds – oval and linear. The oval is more important and is associated with one of the most important subjects in scenes – the vessels. To vessels fall chalices, which Christ hands to apostles in the scene Eucharist, fonts, in which Christ, Holy Virgin and other holy figures are immersed in Nativity scenes, various vessels on the table in the Last Supper scenes, etc. All those vessels, without exception, are depicted in oval reverse construction. This is the language of icon.

In this construction I see the following theological sense. It has long been known that the oval expresses the divine nature of things, while linear form expresses their earthly nature. The nimbus is clearest proof. Nimbuses are round – of all saints who are depicted in their hypostases. Linear nimbuses belong of people depicted in their earthy life time. All mouths in vessels are oval and all are inclined to the pictorial plane, reveal their contents. The language of icon and of any other Byzantine image shows the priority of contents over the form. What matters is the inner contents, not the outer form of an object. Meanwhile, the bottoms of vessels are generally depicted as a straight line, expressing the ground, the earthly. In this sense one and the same vessel expresses the two natures of Christ, because every image in Byzantine painting is Christocentric. And so on, I can give you many examples, but here is not the place.

One of the main reasons that knowledge to be lost is that any rule of Byzantine theology and Byzantine iconography was not written – on paper or otherwise. If we now know something about certain rules of Byzantine theology (but not all), it is because of decisions of Ecumenical and other Councils. But the decisions of Ecumenical Councils discuss and complement the existing rules of Byzantine theology, without entirely express them. They only partially reveal Byzantine theology. We have no written corpus of Byzantine theology, nor of Byzantine painting. And the reason is in the fact that Byzantine theology and Byzantine iconography are related with rules of sacrament. Recorded on paper sacrament is not a sacrament at all, but becomes available to all. Therefore rules of Byzantine theology and Byzantine iconography were distributed only by oral way – by mouth to mouth, to keep the liturgical sacrament.

3. Indeed Chalcedonical view is that Christ has two natures, but one essence. Byzantine painting never depicts His in two separated natures. You will never see Christ depicted only as a human or only as God. In the first type He will be like all of us, and in the second type He simply can not be depicted because of His Divine not-depictioness in consubstantiality with the Father. Therefore Christ, and every other person in the Byzantine iconography, is depicted only in their one hypostasis, in their connection with God. So I say that neither Christ, nor Virgin, nor any other person, depicted through icons, frescoes, miniatures, etc., are depicted in two ways. Each person is depicted only in one way – hypostatic. This is a fundamental and inviolable rule in Byzantine iconography.

4. Here is open the place for violations of professor Kordis. He inserted external ingredients in his images that have never been applied in Byzantine painting. Thus he changes the structure of hypostatic image and violates consubstantiality of God. So I think fully determined that his images are not and can not be icons. We have no right of personal creativity regarding the language of icon.

With best and hearty wishes,

Alexander Stoykov