Similar Posts

On June 2, Saint Vladimir’s Seminary’s ambitious Arvo Pärt Project wrapped up with the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir performing Arvo Pärt’s Kanon Pokajanen (1997) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Temple of Dendur. The Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, under the direction of Maestro Tõnu Kaljuste, is one of the world’s premier choirs, and their performance that night was no exception. They sang with a wonderfully rich and polished sound, maintaining seamless ensemble and flawless intonation for an hour and a half of intensely focused singing. The concert received a glowing review in the New York Times, so instead of speaking about details of the performance, I want to reflect on my own perception of Kanon Pokajanen as a composition and the way in which it provides a fascinating glimpse into the role of an Orthodox artist working outside the liturgical realm.

Kanon Pokajanen is a challenging work, both for the performers and the audience. On the face of it, it seems almost achingly simple, inhabiting a single tonal area in an unremittingly minor mode for the entirety of the piece, and employing oft repeated rhythmic and textural motifs. However, the work is actually intricately organized and deceptively difficult to perform. The text of the Canon of Repentance (found in most Orthodox prayer books), presented here in Church Slavonic, is the governing force in the work, and everything in Pärt’s setting of it, both on the overarching formal level and on the minute level of individual musical gestures, revolves around the text. The text is deeply penitential, and the music, proceeding as it does from the heart of a devout Orthodox believer who reportedly lived closely with this text for a number of years as he worked on the piece, attempts to foster in the listener something of the penitential experience that engendered the words.

Kanon Pokajanen is a challenging work, both for the performers and the audience. On the face of it, it seems almost achingly simple, inhabiting a single tonal area in an unremittingly minor mode for the entirety of the piece, and employing oft repeated rhythmic and textural motifs. However, the work is actually intricately organized and deceptively difficult to perform. The text of the Canon of Repentance (found in most Orthodox prayer books), presented here in Church Slavonic, is the governing force in the work, and everything in Pärt’s setting of it, both on the overarching formal level and on the minute level of individual musical gestures, revolves around the text. The text is deeply penitential, and the music, proceeding as it does from the heart of a devout Orthodox believer who reportedly lived closely with this text for a number of years as he worked on the piece, attempts to foster in the listener something of the penitential experience that engendered the words.

It’s no easy task for a composer to create an experience of penitence in his audience. Most of Arvo Pärt’s listeners probably don’t share his Orthodox Christian beliefs—he is the most performed living composer in the world, after all—but even if they did share his beliefs, how does he as a composer evoke a spirit of penitence in his listeners? Certainly, a composer has to rely on text to convey specific concepts. However, speaking as a lifelong Orthodox Christian, and a sometime composer as well, I can say confidently that simply hearing or reading or even singing a given text does not guarantee that it will create any discernible effect in the heart. It often won’t even be understood. And yet, sitting in the audience at this concert on June 2nd, I can say with equal conviction that I think I experienced something of the penitential spirit with which Arvo Pärt endeavored to imbue this work, and I don’t think I was alone. There were probably a thousand people in the room that evening, and I could scarcely hear anyone draw breath. Anybody who regularly attends concerts in New York City will know how unusual this is.

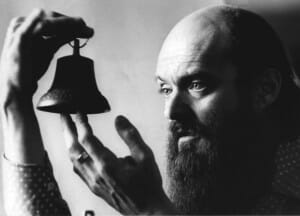

So how does he do it? Much has been written about Arvo Pärt’s characteristic compositional technique called tintinnabuli (from the Latin tintinnabulum, meaning “a bell”), where one voice or set of voices slowly arpeggiates the tonic triad, in a bell-like manner, while another voice or set of voices weaves a diatonic melody line in the midst of it.  As in Pärt’s earlier works in which his tintinnabuli style was being established, like Tabula Rasa (1970) or Spiegel Im Spiegel (1978), Kanon Pokajanen uses tintinnabuli to great effect. However, I want to speak about another feature of Pärt’s work: that is, his remarkable ability to shape the listener’s perception of time and, through this shaping, to invite the listener into a sort of struggle with his or her thoughts. Also, having recently performed a portion of Kanon as a member of a choir, I want to recount something of my experience of this same reshaping of time and consequent battle with the thoughts from the perspective of a singer.

As in Pärt’s earlier works in which his tintinnabuli style was being established, like Tabula Rasa (1970) or Spiegel Im Spiegel (1978), Kanon Pokajanen uses tintinnabuli to great effect. However, I want to speak about another feature of Pärt’s work: that is, his remarkable ability to shape the listener’s perception of time and, through this shaping, to invite the listener into a sort of struggle with his or her thoughts. Also, having recently performed a portion of Kanon as a member of a choir, I want to recount something of my experience of this same reshaping of time and consequent battle with the thoughts from the perspective of a singer.

First, a listener’s perspective. Kanon Pokajanen is a lengthy work by any measure. Few of even the longest major symphonies last more than an hour, and many of these, at least the ones that listeners are used to hearing, move from heights to depths, from raucous to hushed, from tender to violent, and from one key or tonal area to another. (Of course, operas and oratorios can last much longer, but these are by nature paired with drama at some level, and so fall into a different category.) Kanon, by contrast, is nearly an hour and a half in length, never ventures out of its original key, and has little in the way of tempo changes or dynamic effects. It is intensely meditative. However, as the piece unfolds, gradually revealing its formal structure and gently shifting its musical emphases to bring out textual phrases, it insists that the listener slow down his perception of time. If you’re waiting for the piece to be over (something common in our impatient age), or if you’re waiting to be carried away by some dramatic change in the music, the piece will seem tedious, if not excruciating. For me, the experience was something akin to jumping into water that’s slightly too cold. At first, I was uncomfortable, and I floundered around for something familiar to hold on to. Then, slowly, I began to adjust to my new environment, and I soon found that by using my mental muscles in a different way—that is, by slowing down my thoughts and allowing them to move in the rhythm that the piece was dictating, like a swimmer adjusting to the temperature and increased resistance of water—I was able to occupy the space of the piece, and to understand something of what it was conveying. The result of this slowing down was that the text, those deeply penitential words, started coming alive in a totally unexpected way. I began to dwell on the words, not simply reading them for sense meaning as I normally would (as you’re probably reading this article right now), but really pondering them and allowing the meaning of each word to penetrate. The experience was not at all tedious, but dynamic and exciting, and profoundly moving. After the reverberations of the final heart-wrenching “Amens” had died away—a piercingly high and thick D-major chord resolving upwards even higher to G-minor, and then, in a lower register, from G-minor back to D-major—the audience sat in rapt silence for a pregnant ten seconds before erupting in thunderous applause. It seems everyone felt the transformative effect of the piece.

Just recently, I had an opportunity to perform the final movement of Kanon Pokajanen as part of a semi-professional choir at an exciting and groundbreaking festival of new music by Orthodox composers in Greaves Concert Hall of Northern Kentucky University, under the direction of Maestro Peter Jermihov. As we rehearsed the piece, I again felt that same sense of being in cold water, this time as a singer. The notes were in an uncomfortable register, the time signature was perpetually changing, and most difficult of all, the periods of singing were constantly punctuated by irregular measures of rest so that I felt like a percussionist in an orchestra, counting furiously so as not to miss a beat. I’m an experienced singer, and a composer and conductor as well, but I could honestly find very little in the piece that was intuitive or predictable; at no point, therefore, could I go on “auto-pilot” and just get into the flow of the piece. Every move had to be calculated, my focus couldn’t waver for an instant, and I was never allowed to wallow in the music. I sensed too that I was not alone in my uneasiness, and I couldn’t help wondering if we would prove equal to the task of giving the piece a worthy reading. However, as soon as we started the piece in the concert, something like a miracle happened. The feeling of focused concentration in the choir was palpable, and the ensemble moved and breathed as a single organism. As we reached the climactic middle section of the piece, I felt as if the sound was being pulled out of us by some invisible force. My own attention was focused mainly on counting rhythms and singing the pitches and Slavonic words accurately, not really on expression or on other features of the sound; but the immense expressive power of the work was there nonetheless, erupting from the ensemble with overwhelming force. By compelling the singers to focus all their attention on counting out notes and rests, Arvo Pärt managed to circumvent our performer’s egos and to create a powerful sense of unity and common intention within the ensemble. Credit also goes to Maestro Jermihov for understanding this and placing primary emphasis on rhythmic accuracy rather than expression during rehearsals, as well as for having the foresight to know that the piece would ultimately come together. After the final “Amens” emerged and the choir walked offstage for intermission, it was clear that everyone felt simultaneously exhausted and elated, as if we had faced death and conquered it.

Just recently, I had an opportunity to perform the final movement of Kanon Pokajanen as part of a semi-professional choir at an exciting and groundbreaking festival of new music by Orthodox composers in Greaves Concert Hall of Northern Kentucky University, under the direction of Maestro Peter Jermihov. As we rehearsed the piece, I again felt that same sense of being in cold water, this time as a singer. The notes were in an uncomfortable register, the time signature was perpetually changing, and most difficult of all, the periods of singing were constantly punctuated by irregular measures of rest so that I felt like a percussionist in an orchestra, counting furiously so as not to miss a beat. I’m an experienced singer, and a composer and conductor as well, but I could honestly find very little in the piece that was intuitive or predictable; at no point, therefore, could I go on “auto-pilot” and just get into the flow of the piece. Every move had to be calculated, my focus couldn’t waver for an instant, and I was never allowed to wallow in the music. I sensed too that I was not alone in my uneasiness, and I couldn’t help wondering if we would prove equal to the task of giving the piece a worthy reading. However, as soon as we started the piece in the concert, something like a miracle happened. The feeling of focused concentration in the choir was palpable, and the ensemble moved and breathed as a single organism. As we reached the climactic middle section of the piece, I felt as if the sound was being pulled out of us by some invisible force. My own attention was focused mainly on counting rhythms and singing the pitches and Slavonic words accurately, not really on expression or on other features of the sound; but the immense expressive power of the work was there nonetheless, erupting from the ensemble with overwhelming force. By compelling the singers to focus all their attention on counting out notes and rests, Arvo Pärt managed to circumvent our performer’s egos and to create a powerful sense of unity and common intention within the ensemble. Credit also goes to Maestro Jermihov for understanding this and placing primary emphasis on rhythmic accuracy rather than expression during rehearsals, as well as for having the foresight to know that the piece would ultimately come together. After the final “Amens” emerged and the choir walked offstage for intermission, it was clear that everyone felt simultaneously exhausted and elated, as if we had faced death and conquered it.

To experience Kanon Pokajanen, either as a listener or a performer, is to taste something of the inner warfare integral to Orthodox spirituality. Moreover, Kanon convincingly reveals that, while the warfare with one’s thoughts and weaknesses may be bitter at times, the transformation that comes from it is amazingly sweet. This is the mystery of repentance. We voluntarily condemn ourselves not out of self-hatred or some kind of masochistic desire for pain, but to pare away everything superfluous, everything banal and impure and ugly, so that the radiant stillness of the purified soul, its power and beauty, can become visible. For a composer to find a way to convey this subtle and paradoxical reality through music—and what’s more, to convince a deeply unbelieving world to listen—is a remarkable achievement, and Arvo Pärt deserves recognition as one of the great composers of our time, perhaps of all time.

As my wife Maria and I were leaving the concert in the Met’s Temple of Dendur, a massive glass-walled room containing a reconstructed Egyptian temple from 15 B.C. that was originally dedicated to Isis and Osiris, we exchanged a few words with one of the concert’s organizers from St. Vladimir’s Seminary. He looked up at the frowning edifice behind us, and said with obvious feeling, “Hearing this music and these words, here, in this place, I feel like somehow the temple has been cleansed.” I couldn’t agree more.

It was interesting to hear the “backstory” on last weekend’s performance at NKU. I would never have known it went poorly in rehearsal, but it obviously was exhausting to perform. Your description of the score tells me why.

“He looked up at the frowning edifice behind us, and said with obvious feeling, “Hearing this music and these words, here, in this place, I feel like somehow the temple has been cleansed.” I couldn’t agree more.”

REALLY? OAJ could be such a great Online Mag if it wasn’t interspersed with so many self congratulatory pompous remarks such as this.

I’m not sure why you think the remark is self-congratulatory and pompous. True, I’m making a qualitative distinction between the ancient worship of Isis and Osiris and an Orthodox Christian spirit of repentance, but I don’t think this is either radical or arbitrary, and it certainly has nothing to with me personally. Unless our modern mores has changed so fundamentally (and maybe it has) that worship involving animal sacrifices and orgiastic celebrations needs to be held on an equal footing with self-purification through voluntary self-reproach and penitential tears, I don’t think talking about Kanon Pokajanen having a cleansing effect is unwarranted or needs a lot of explanation.

However, even if you don’t agree with me on this point, I hope you see that stating a belief of one religion’s superiority over another is a fundamental right of any religious believer. What else is a religious believer? I make no secret of my Orthodox beliefs, and I am an Orthodox Christian because I believe that it possesses truths that other religions do not. You may, of course, disagree with me—I fully expect you to if you don’t share my religious beliefs—but I would hope that you would respect my right to say what I believe without assuming that I am personally congratulating myself on my beliefs or being pompous.

Arvo Part’s reputation as a “holy minimalist” shows throughout his pieces. His works are brilliant – and brilliantly performed! The world is fortunate to have such a uniquely gifted man.

I’m very grateful, Benedict, for your thoughts on Part’s music. Your interpretation of the structure and tempo of the music as corresponding to the experience of ascetic struggle is convincing, and considerably helps me to understand the music. This reminds me very much of our discussions about liturgical music – whose purpose is to push our minds towards a state of self-emptying, and thus, prayer. It is amazing that a secular audience, who would bitterly resist subjecting themselves to this phenomenon in a church service, willingly do so in a concert!