Similar Posts

I was asked, in 2015, to design a set of liturgical furniture for Annunciation Greek Orthodox Cathedral in Baltimore. When I looked at the building, I could see that this would be a complex project with several stylistic influences in play. The monumental structure was built by a Protestant congregation in 1888 in the ‘Richardsonian Romanesque’ style, popular in America at that time. It is a wild mixture of Romanesque forms and Byzantine ornament, designed around a Protestant church-in-the-round sort of plan. It was purchased by the Greek congregation in 1937, and converted to Orthodox use with very few changes.

The original woodwork in the cathedral is unusually fine quality. Typical for Victorian churches, it is made of quarter-sawn oak with a dark ammonia-fumed color. The woodwork is massive and robust, with generous use of arches and curves, imitating the Romanesque stonework. I felt strongly that any new furniture I designed would need to match this quality and harmonize with its style. But it also would need to connect to Greek Orthodox traditions of furniture design and ornamentation. I found a solution by looking at Greek woodwork from the 16th and 17th centuries, when Greece was under the influence of Venetian art. During this period, we see Greek woodwork that emulates Italian Renaissance forms, while still keeping one foot in a medieval aesthetic. I thought that with this mixture of influences, I could achieve something that looks both Greek and Romanesque and the same time.

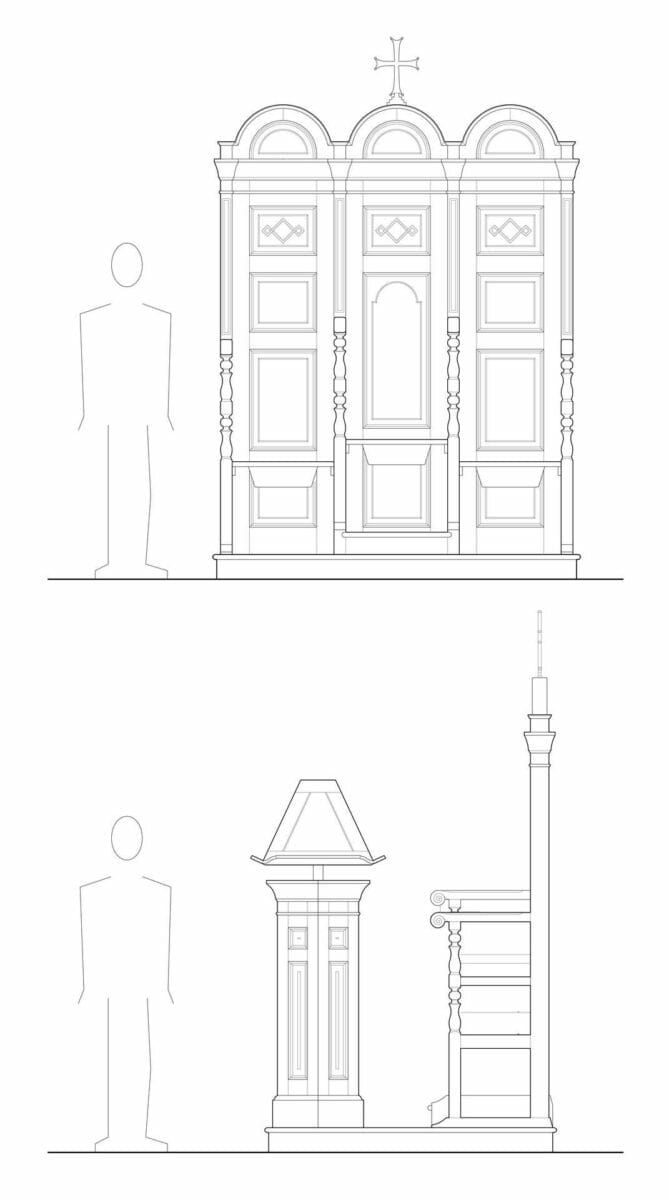

The first project was to be a set of three conjoined stasidia with a rotating music stand for the chanter. This is a traditional form in the Greek tradition, designed around some very specific acoustic and ergonomic needs for a choir of three Byzantine chanters. Fr. Andreas Houpos, at that time a chanter at the cathedral, advised me in detail as to how it needed to function. I designed my version with the massive paneled-oak construction of the original cathedral woodwork, with arches at the top like a 17th-century Greek iconostasis, and a Byzantine cross as the finial.

The first project was to be a set of three conjoined stasidia with a rotating music stand for the chanter. This is a traditional form in the Greek tradition, designed around some very specific acoustic and ergonomic needs for a choir of three Byzantine chanters. Fr. Andreas Houpos, at that time a chanter at the cathedral, advised me in detail as to how it needed to function. I designed my version with the massive paneled-oak construction of the original cathedral woodwork, with arches at the top like a 17th-century Greek iconostasis, and a Byzantine cross as the finial.

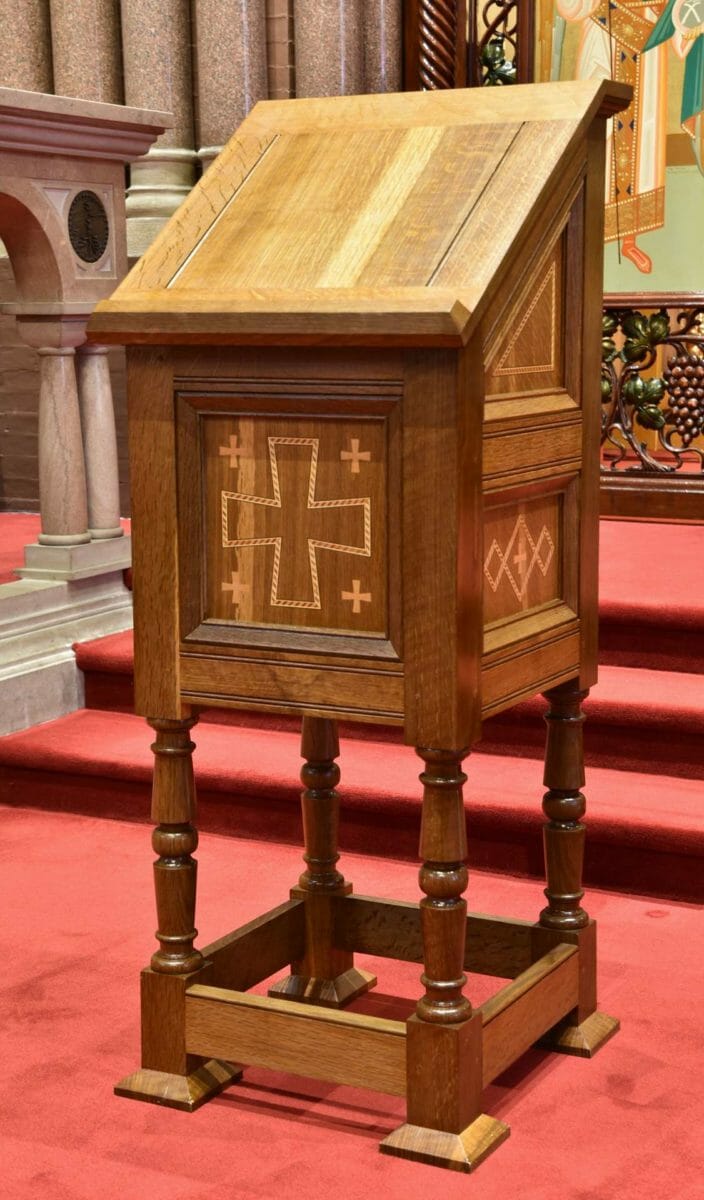

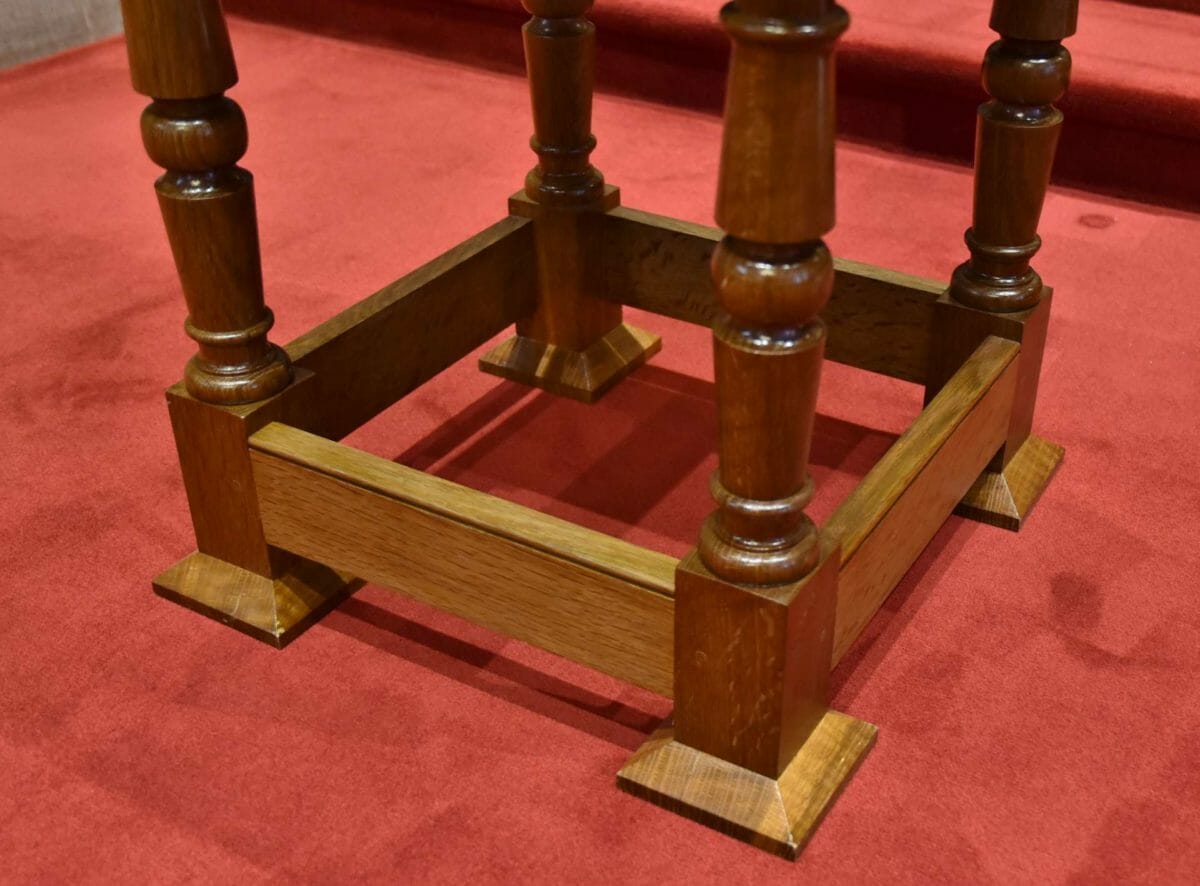

The second project was a pair of icon stands. I’ve seldom seen an icon stand that I thought was a completely satisfactory design, so I gave this considerable thought. Ultimately, I decided to base the structure for these on Jacobean English furniture, with turned legs and heavy rail-and-stile construction. This structural system has a certain logic and sobriety that works quite well for the purpose.

I decided to ornament the furniture primarily using inlay rather than carving. As with most churches, the cathedral is dark inside and the diffuse light casts no shadows. Carving does not read well in these conditions, whereas contrasting inlay looks rich and beautiful. This technique also connects the furniture to 17th-century Greek traditions. We can see marvelous inlaid furniture from this period at the Phanar, and on Mt. Athos, for instance. (Inlay was, at that time, far more typical than carving, which rose to prominence in Greek woodwork much more recently.) For the inlay, I used banding with contrasting light and dark woods, and on the backs of the stasidia, three seraphim carved from boxwood by Jonathan Pageau.

I hired Bruno Sutter, a professional furniture maker, to make the pieces. He used premium quarter-sawn white oak – a very fine material, and hard to obtain because it almost all goes to barrels for the craft spirit industry. It is impossible to darken oak satisfactorily using stain. The only way is to use ammonia fumes, which react with the tannins in the wood, bringing out a particular grain pattern. Ammonia fuming is rarely done nowadays, because it is difficult and hazardous, but there is no other way to match old oak woodwork. Bruno built a huge tent in his workshop for this purpose, and the results came out beautiful. We then applied five coats of amber and clear shellac followed by paste wax.

The cathedral is immensely pleased with their new furniture. It is rare that Orthodox liturgical furniture of this quality is ever made nowadays. I was happy to be able to have it done in America, where we have a strong tradition of fine furniture making and excellent quality woods. It is many steps above work that can be readily obtained from overseas, and I hope it serves as an inspiration for Orthodoxy in America.

Designer: Andrew Gould (New World Byzantine / NWB Studios)

Furniture Maker: Bruno Sutter (Timber Artisans, LLC)

Wood Carvers: Jonathan Pageau and Mary May

Wood Turner: Ashley Harwood (Turning Native)

Inlay Banding: El Henson

Design drawings:

Some images of the furniture under construction:

Some images of the original (c.1888) woodwork in the cathedral:

Beautiful design and work, Andrew. What a marvelous opportunity and felicitous outcome! Thank you for this interesting account and pictures of the process. I’m sure I speak for countless others, who share the hope expressed in your final sentence…

I have seen these in the flesh and must say that, aside from being very beautiful, they are the sturdiest stasidia and psaltiri that I have ever seen. Well done!