Similar Posts

Beauty cannot compel, but it can call. Liturgical art and worship, when well executed, is a fragrance of paradise that beckons us to find its divine source. In this article I want to discuss one particular role of liturgical art: to help open the eye of our heart, or the nous as it is called in patristic Greek and intellectus in Latin.

Liturgical art is a science as well as an art. Its creators need to know precisely the purpose of their work, otherwise their designs will be arbitrary. Each sacred art – such as lamps, icons and hymnography – has an immediate role, to give light, to be venerated, to praise God or teach the faithful. But together they have this other role, to create an atmosphere conducive to prayer of the heart, compunction, stillness, humility, awe. Aesthetic choices for the liturgical artist are guided by these roles.

What is meant by the eye of the heart, or intellect as it is translated in the English Philokalia? In their glossary the translators say this of it:

Unlike the dianoia or reason, from which it must be carefully distinguished, the intellect does not function by formulating abstract concepts and then arguing on this basis to a conclusion reached through deductive reasoning, but it understands divine truth by means of immediate experience, intuition or ‘simple cognition’ (the term used by St Isaac the Syrian).

It is this noetic faculty that needs to be opened for us to experience and be changed by what God has already done in Christ. Paul writes that:

The unspiritual [psikikos in Greek, literally “soulish”] man does not receive the gifts of the Spirit of God, for they are folly to him, and he is not able to know them because they are spiritually discerned. (1 Cor. 2:14)

Paul speaks here not of the carnal (i.e. fleshly) man but of the person who remains in the realm of the soul, soul meaning in this case the rational and bodily faculties but not the spirit. These soulish faculties of reason and physical senses are of course good and God-given, but of themselves they can only assimilate things pertaining to the material world.

The way an icon is painted comes of this noetic way of seeing and in turn is designed to introduce the faithful into this noetic way of seeing. Just before the verses quoted above, St Paul writes:

.. Now we have received not the spirit of the world, but the Spirit who is from God, that we might understand the things freely given us by God. And we impart this in words not taught by human wisdom but taught by the Spirit, interpreting spiritual truths in spiritual language. (I Cor. 2:12,13)

That is to say, spiritual things need explaining or manifesting in a spiritual way. So what makes icons and other good liturgical arts so powerful is not just their sacred subject matter, but the way this subject matter is expressed. An icon crudely or sentimentally painted still acts as an icon inasmuch as it connects us with its prototype through the saint’s name that it bears. But it fails inasmuch as its “style” or language does not satisfactorily evoke the transfigured world. Similarly, a church building can protect the congregation from the elements but by poor design fail to give them the sense of the incarnate God dwelling in their amidst.

To see with the eye of the heart we need first to be purified, to repent, to turn towards God. Liturgical art can assist this turning through its “joyful sorrow”.

Its aesthetics are ascetic. Liturgical beauty fosters compunction not euphoria, for it is only through obedience and love that one can encounter the living God. This is why in monastic all-night vigils darkness has as much a role as light. The darkness helps the monk descend into the heart and pray. The lighting and swinging of the chandeliers at the high points such as the Praises (Lauds) offers relief from the strain of prolonged concentration in prayer, gives a foretaste of heavenly joy, and suggests the praises of “sun and moon, all you stars and lights”, as the Psalmist says.

All the above are to do with timeless and eternal things. But there is another essential aspect of church furnishing: because it is incarnational it is an offering of a specific culture. Just as at Pentecost each person heard the wonders of God in his own tongue, and so a church building and its interior ought to draw on all that is good in its home culture, be this Canada, New Zealand, Kenya, England, Greece or wherever.

A case study

I would like to illustrate what I am saying by describing a chapel that I made from a small converted barn at the Hermitage of Saint Anthony and Saint Cuthbert, Shropshire, England.

The aim was to make a cave-like atmosphere that was both warm and inviting, but deep enough in its colouring to quieten the soul and be conducive to inner prayer. The budget was limited, so I used a lot of recycled wood.

Having levelled and insulated the floor I lay a wooden mosaic (parquet) floor.

The geometric designs are symbolical of life in Christ in the Church. On entrance one finds a square, which symbolizes creation. A little further on, in the centre of the nave, is a square united to a circle through eight spirals. This represents the Church, which is the divine Christ (the circle) united to our humanity (the square) through the eighth day resurrection. At the foot of the Holy Table is a square surmounted by a semi-circle which extends into the nave. The square consists of arrows coming out from the Holy Table – God’s movement out to us – and arrows moving towards the Holy Table – our offering of ourselves and all creation to Christ. The semi-circle like a wave is divine life sent into all the world through Pentecost.

The icon screen was then made using materials and techniques traditional to English furniture. It is of oak, with scratch moulding and mortise and tenon joints held with hand-made pegs.

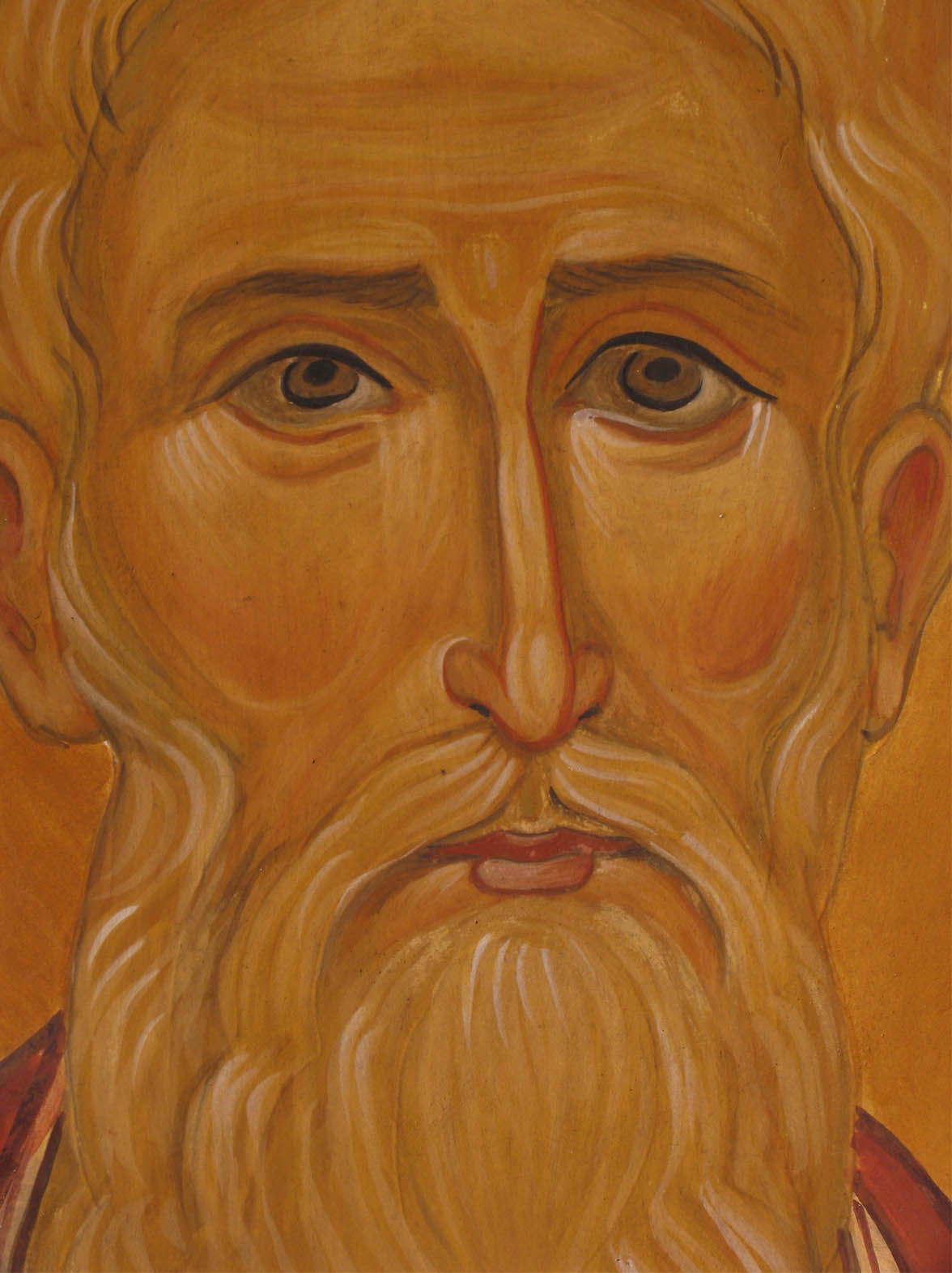

For the colouring of the icons I concentrated on a cool blues and warm earth reds with burnished gold backgrounds.

Throughout the chapel the emphasis was on the union of man and all material creation with God, hence the combination of earth colours and heavenly blue, and wood with gold. Drawing on the local Welsh tradition, I added Celtic knot work to the base of the Annunciation Royal Doors.

The ceiling I made from timber panelling stained a reddish brown, and inserted an octagonal Pantocrator icon in the centre. I like to think of the Pantocrator not only as the all powerful ruler but also as the skilful conductor of the cosmic orchestra.

Beautiful hand woven curtains and analoi hangings were especially commissioned from the weaver Elza Tantcheva. Again, deep reds, blues and gold were the dominant colours.

The next task was to fresco the walls. My aim was to create a space of stillness where people could more easily enter the paradise of the heart, there to walk with Christ. All the pigments I used are natural: lamp black and lime for the deep blue-black background; red and yellow ochres; green earth; umbers; raw sienna for the haloes. Around the top are scenes in the life of St Cuthbert on one side, and of St. Anthony the Great on the other. Beneath are saints from around the world, including David of Wales, Isaac the Syrian, Seraphim of Sarov, and Mary of Egypt.

The design of the solid silver censer was inspired by a seventh century work. The wooden table for the relics and beeswax candles I made of local Scots pine and a panel of mahogany rescued from a rubbish bin.

I will never forget the day when a truck driver came to the hermitage to deliver his 15 tons of sand. He wasn’t a believer, but I asked if he would like to see the chapel. This great brawny man, covered in tattoos, entered he chapel. He stood still for a long time, and began to cry. There was no denying that something had happened in his heart. He had caught a waft of fragrance from the garden of paradise.

Glory to Jesus Christ!!!

Your work is just simply beautiful!!!

Thank you, Robin. I am always aware of the gap between my work and the divine beauty they try to express, so it is encouraging to hear when they do enter the heart!

Thank you indeed Aidan for elaborating on your aesthetic choices and how you made them. It’s not often that we get an insight into the design of a chapel interior; it’s a real gift of the Holy Spirit to create such a prayerful space that can evoke the response you described from the lorry driver. Naturally it makes one want to visit the chapel for Divine Liturgy. Thanks again.

Excellent post, and really beautiful work; I would love to visit that church some day. It’s interesting to see the worship of the Orthodox Church described as ‘ascetic’ when it seems so rich compared to other sects of Christianity. But I think part of the oddness to my ears has to do with a view of asceticism as necessarily negative rather than, what it is, a ‘training’ whose goal is both proper joy in creation and proper sorrow for the sin that mars it

Thank you, Jeremiah, and I quite agree with your understanding of ascetic beauty. As well as thinking of virtue in moral terms, it can be equally thought of as the restoration of the beautiful image of God in the human person – and sin as its deformation.

Thanks, Mark. Let’s pray that more people are raised up who can help create whole church interiors which are an icon of heaven, and not just an assemblage of disparate parts.

Love the frescos, they have a real air of honesty about them.

Absolutely stunning. Your work here and its evident impact on the truck driver sum up my own personal belief in the power of beauty to speak to the human heart of God. Love the choice of colours you have used to aid in stilling the heart and mind of the worshipper. Must visit this place.