Similar Posts

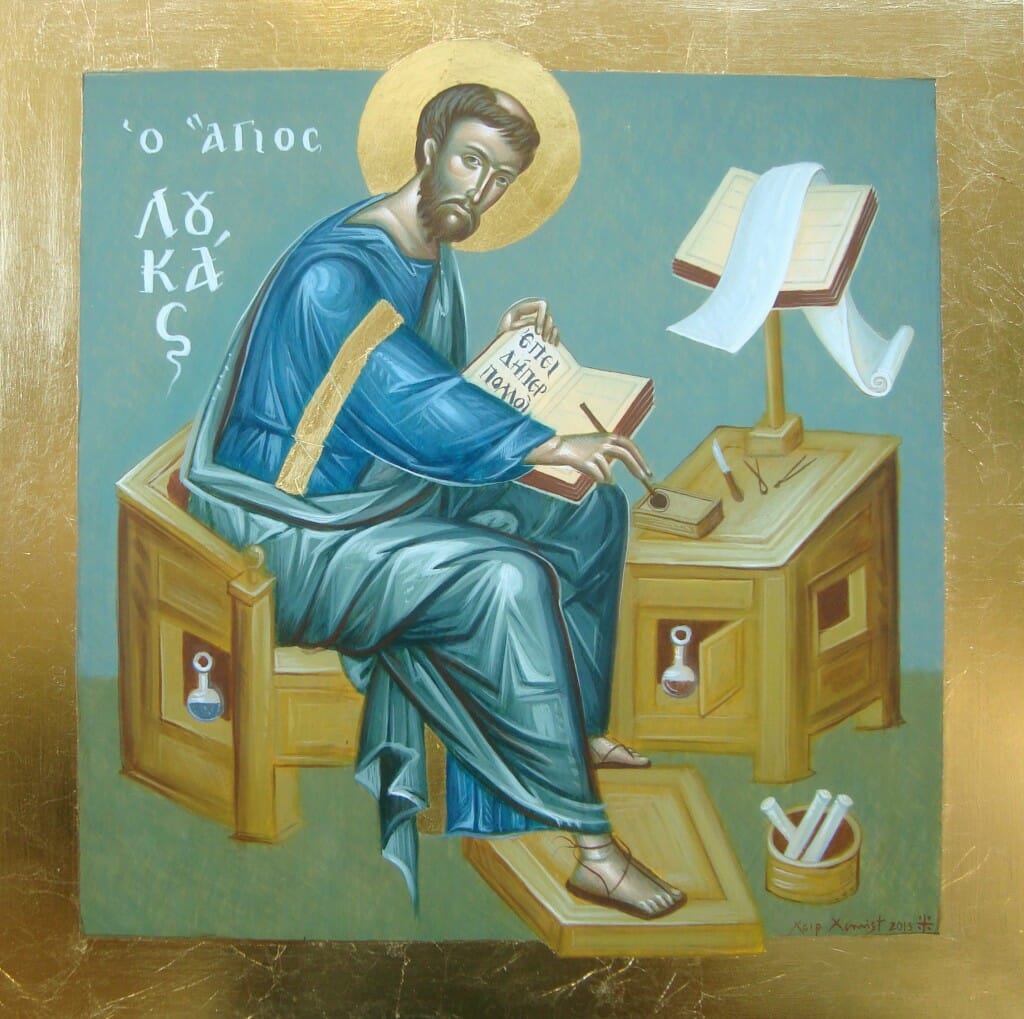

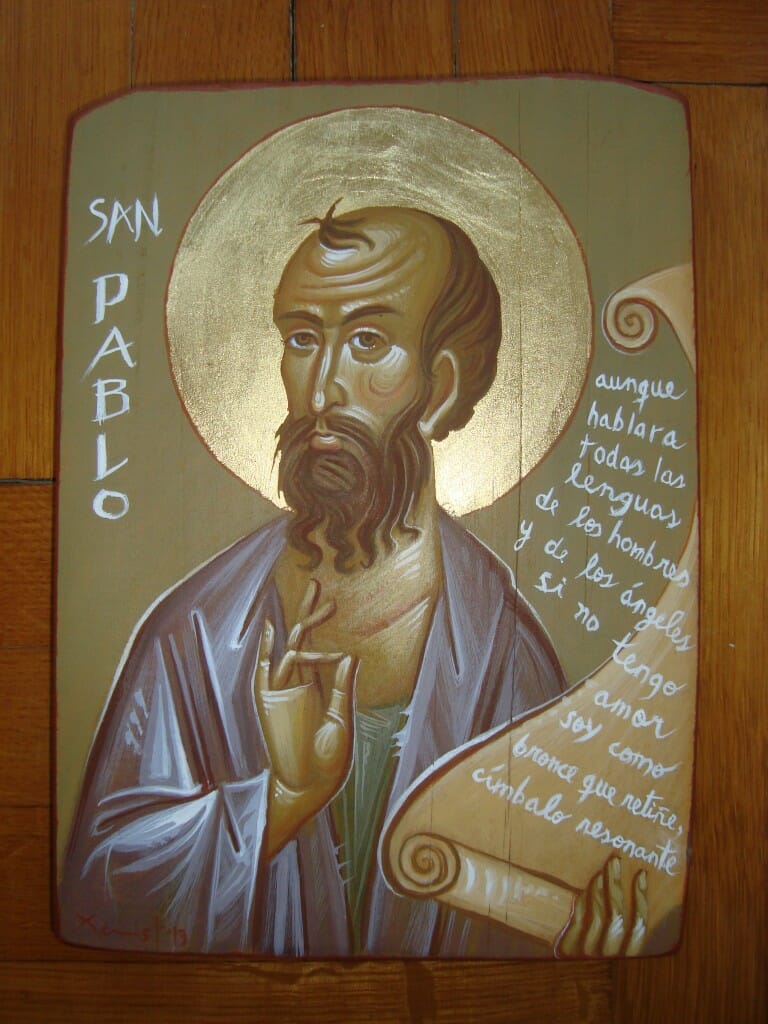

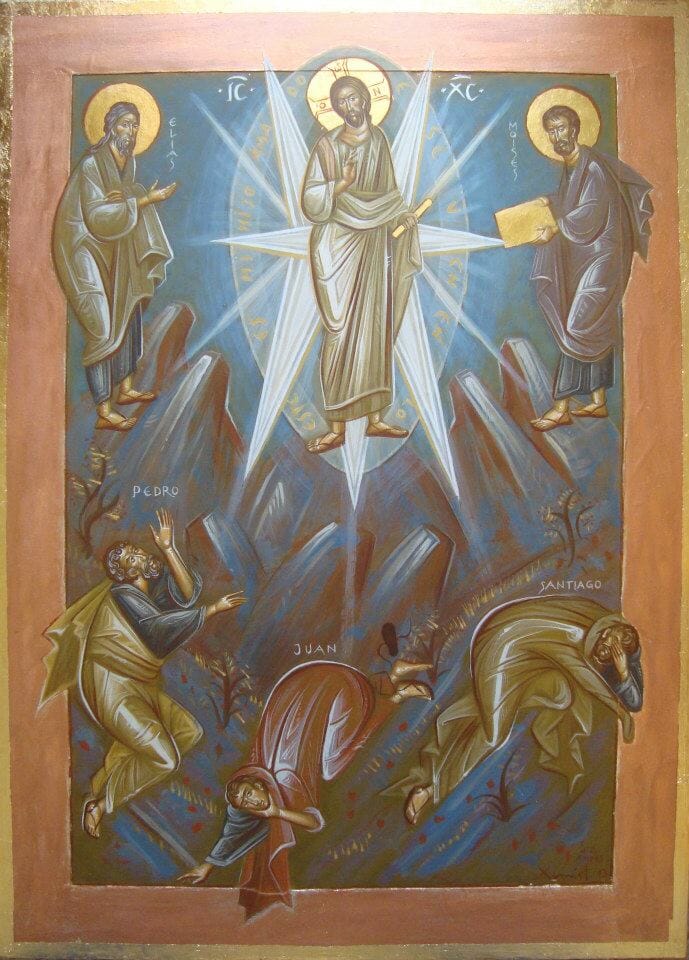

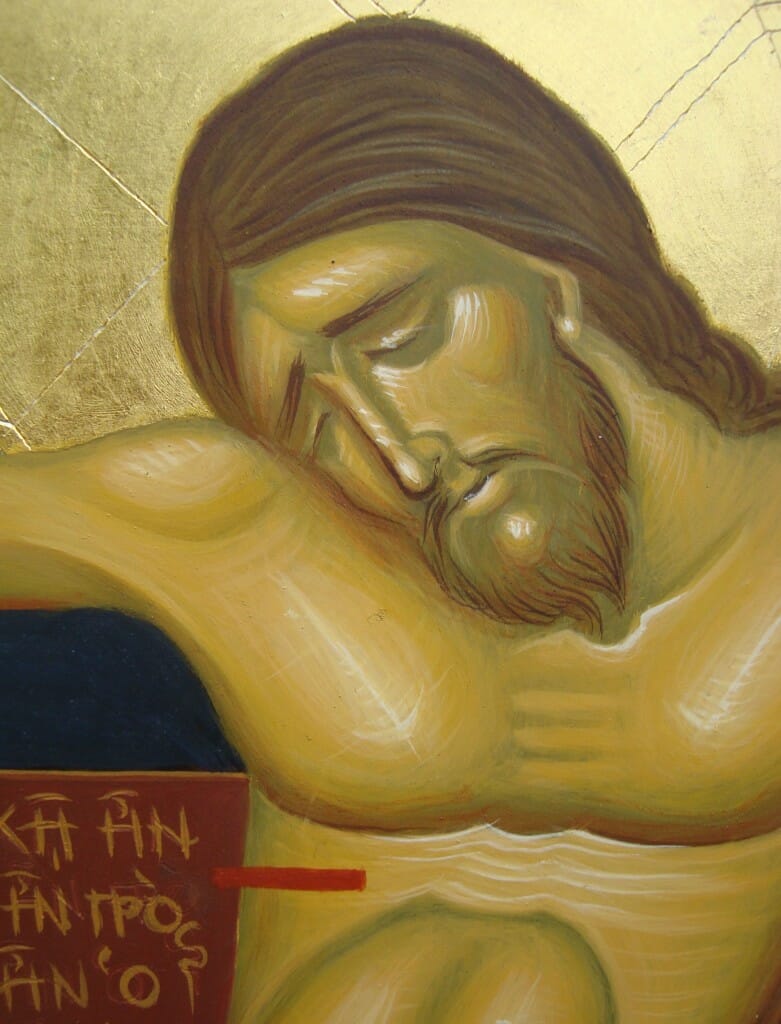

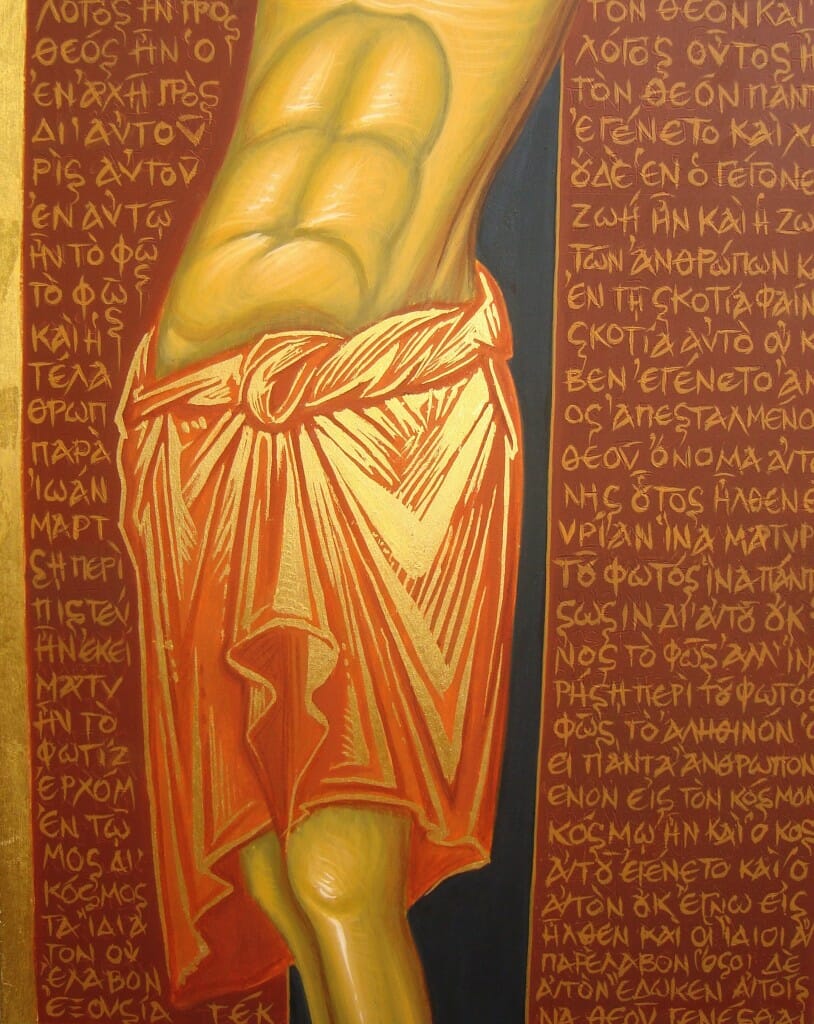

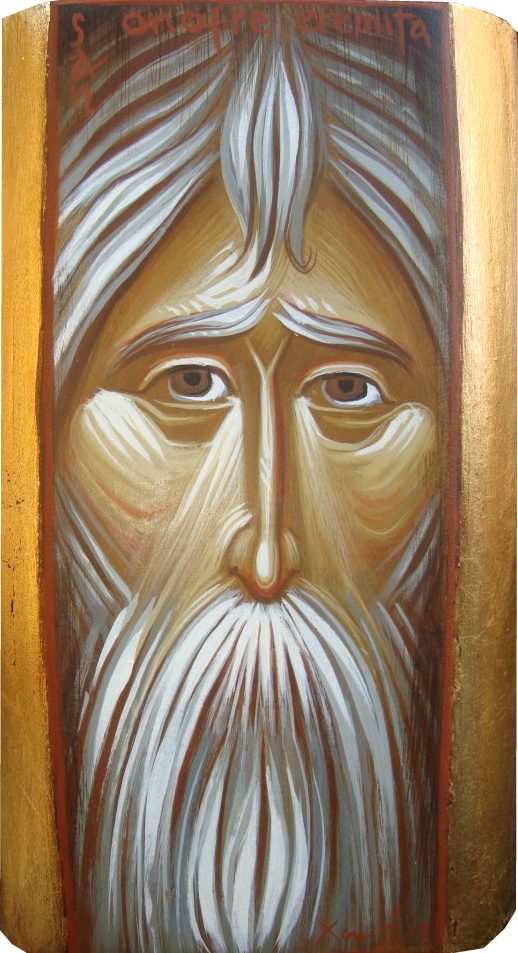

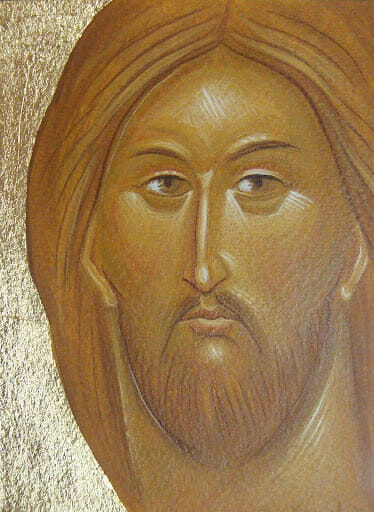

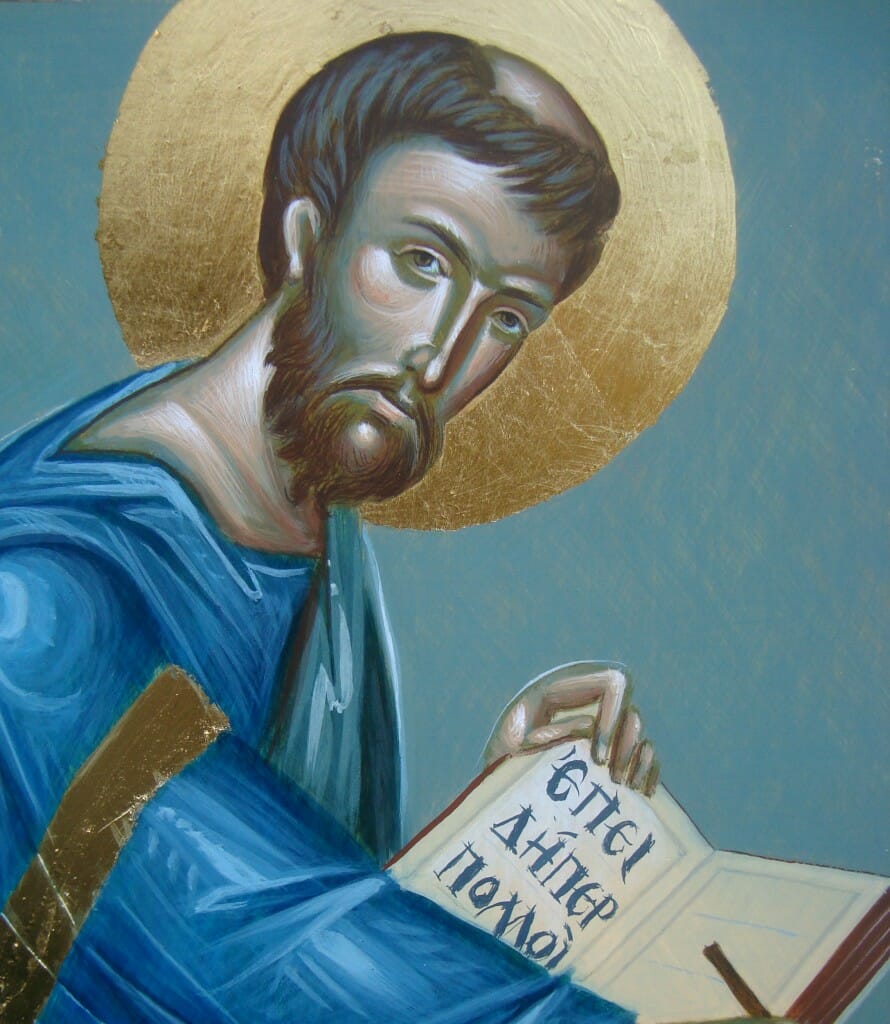

Federico José Xamist is a remarkably talented young iconographer of whom we have recently become aware. His work exemplifies icon painting as a fresh and living tradition. We offer the following interview to introduce this exciting artist to our readers:

Gould: Federico, you grew up in Chile. How did you come to live in Greece?

J. Xamist: When I left Chile in 2002 and went to Spain, I think I was not really aware of what I was doing, and the same goes for what I feel regarding Greece. I was studying Classical Philology in Barcelona, and came to Greece in 2005 because I wanted to see and feel that wonderful world which I used to know only from words and images. In this trip I met Irini, my wife, and went to Mount Athos. These two experiences decisively contributed to placing my life in its deeper mystery. So, once I finished my studies in Spain I followed this sign; I moved to Athens and got married to Irini.

Gould: And how did you discover icon painting as your vocation?

J. Xamist: Icon painting had caught my attention long ago, when I was studying Architecture in Chile and watched Tarkovsky’s film, “Andrei Rublev”. I loved Tarkovsky’s poetics, which, in my opinion, could not be separated from the Orthodox faith experience and the icon painting tradition in particular. After that, I became familiar with the work of Pavel Florensky, “The Reverse Perspective”, where he analyzes the significance of the representation of space in the icon. Florensky’s work was the result of a series of seminars that took place in the experimental school of VKhUTEMAS, breeding ground for the development of the Russian avant-garde.

So, this connection between the tradition of icon painting and the origin of modern art seemed to me very interesting and I realized that it could include the different facets of my personal academic and artistical quest. However, the turning point in my discovery of the icon painting tradition was my coming to live in Greece.

Gould: Tell us about your studies in icon painting. What sort of educational environment did you find, and what is it like learning from George Kordis?

J. Xamist: In Greece, I verified this current character of the icon painting tradition and I realized that it was a determinant factor for the development of modern Greek culture. Actually, in George Kordis’ work (both as an author and as a painter) I recognized these elements, so I tried to meet him. He was really generous with me and he encouraged me to follow the courses of the Centre of Orthodox Icon Painting Studies and Research Eikonourgia, managed by him, and later on, he tutored my Master thesis in the Faculty of Theology of the University of Athens. In Eikonourgia I found a team of qualified people, who dealt with the icon painting as a contemporary artistic practice, aware however of its liturgical and ecclesial dimension. In addition, in Eikonourgia there were students from all over the world, which enriched even more the learning environment.

Gould: Are there particular historical pieces or styles that have especially influenced your work?

J. Xamist: At the beginning, I only had knowledge of the so-called Russian School, and in particular about the figures of Andrei Rublev and Theophanes the Greek. Later on, in Greece and with the help of Kordis, I noticed the variety of styles that there are in the icon painting tradition and that they change over time. In this regard, if one wants to learn to paint an icon (and not only to copy old icons), the most important thing – what can actually be taught – is the way (tropos) in which the icon painting tradition embodies the ecclesiastical experience. In other words, how the drawing, the color and the composition work in order to constitute here and now the ecclesiastical body. That does not mean at all that the works of the past should be ignored, but that the study of the tradition must have as a starting point the understanding of this pictorial way – above all when one wants to learn to paint an icon and not merely copy it.

With this in mind, I could say that I admire the clearness of the drawing in the Russian school, but I have also learned a lot about color and how it works in Byzantine painting by studying the so-called Macedonian school. There are also contemporary iconographers in whom I am very interested, such as the Greek Michalis Vasilakis, whose work was the subject of my MA thesis, or some people from Romania and Ukraine.

Gould: And what about your more unusual and experimental work? What are your trying to achieve with these pieces? Do you consider them all to be ‘icons’ in the liturgical sense, or are they something else?

J. Xamist: With the icons I paint I am not trying to do something different or new; I am just trying to participate in the ecclesiastical experience. I think that this is possible only when we live within the tradition. That means ‘using’ the tradition rather than watching it from a distance, like a museum object. On the other hand, the icon’s liturgical sense is precisely to ‘serve’ (this is what the word ‘liturgical’ means in Greek), to ‘help’ to configure the ecclesiastical reality here and now. Nowadays, there is a tendency to talk about an iconographic canon based on the theology of the Church Fathers, but you cannot find any information about how the icons must be painted, neither in the Fathers’ works nor in Ecumenical Councils. The only texts that talk about how to paint are some manuals (such as Ermineia of Dyonisius of Fourna, 18th century), however their character is not ‘canonic’ but auxiliary.

The invention of an iconographic canon is a process which started in the 15th century, when the Byzantine Empire disappeared and icon painting (called maniera greca) had to be differentiated from the Renaissance painting (the maniera italiana). Later, at the beginning of the 20th century, when the icon painting tradition was ‘rediscovered’, this supposed canon gained again in importance so that it could be differentiated from modern painting (when actually this ‘rediscovery’ took place, exactly because modern painting releases visual art from the naturalist canon!!!). I think that the natural need to understand how icon painting works is often distorted and cultural and historical facts are confused with theological notions. That, in my opinion, has become many times an obstacle for the development of the ecclesiastical arts.

Gould: Can you say something about the technical aspects of your work? Is there anything unusual about your materials or technique?

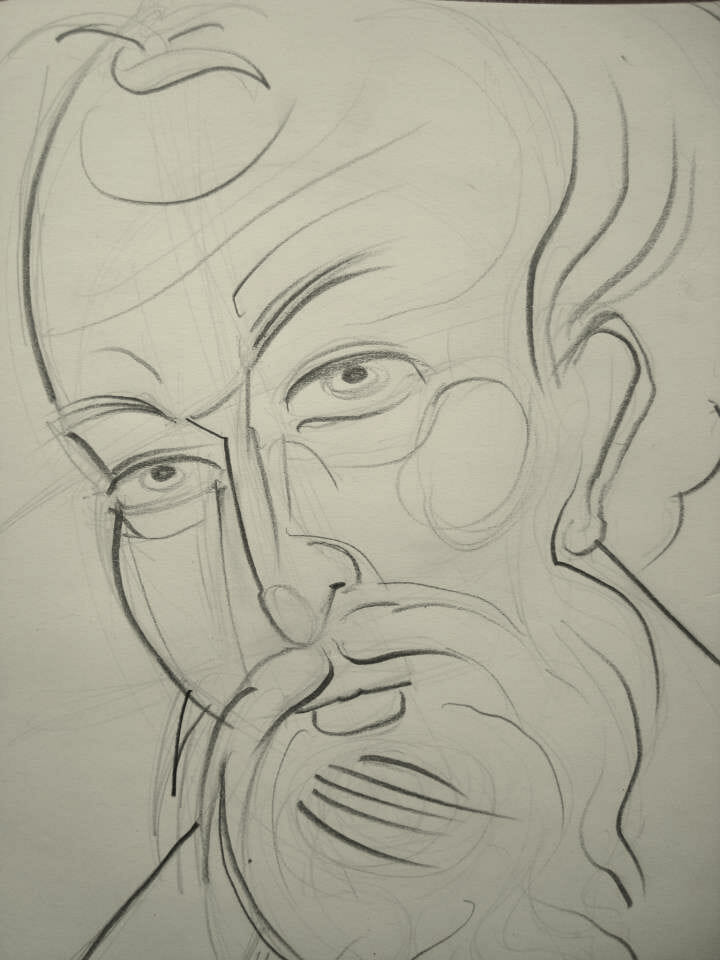

J. Xamist: I do not think that there is anything unusual in my way of working. I paint with egg tempera on wood and use most of the times only the four pigments of the ancient Greek tetrachromy (black, white, red and ochre). The wood can be prepared in many different ways. Many times I glue a hand-made paper on the wood instead of the so-called ‘levkas’. The actual tradition provides so many ways to work and none of them is better than the others, it all depends on what you want to do. What is indeed important for me is to do the drawing myself, i.e. not trace. So, after seeing different examples of the same iconographic type, I try one of them or take many elements and carry out the drawing. But actually I feel that I am just starting. There are so many things to learn from the tradition and from other contemporary iconographers.

Gould: Your work has the life and energy of some of the best medieval Byzantine icons. This is so refreshing to see, especially coming from Greece, where most contemporary icons are quite opaque and formulaic. How do you achieve this lively spontaneity in your painting?

J. Xamist: I really thank you for the comparison, but maybe it is excessively generous. If somebody happens to feel something with my work and can glimpse the ecclesiastical experience, I can only attribute it to God’s grace, which works through me – through the matter and through the person seeing the icon.

Gould: How would you characterize the state of iconography in general in modern Greece?

J. Xamist: I agree with you about the formulaic character of a lot of contemporary icons, but this is not the case only in Greece. In Greece, at the beginning of the 20th century, just like in Russia, there were a lot of modern artists who saw in Byzantine art a way of modernity and a bridge for their own understanding of the Greek Antiquity. Maybe the most important figure concerning icon painting’s revival at the 20th century in Greece was Photis Kontoglou. He researched and restored the traditional techniques of icon painting from a pictorial point of view, and used this way of painting for making modern art. On the other hand, for Kontoglou icon painting was an authentic way of living the ecclesiastic experience. What Kontoglou attempted was really hard, because at the time there were very few who believed that the icon painting was a live tradition. Most of the people saw in it either an exciting and exotic mode of expression or simply a primitive art. For this reason, maybe as a sort of protection, Kontoglou ends up closing the dialogue that he had opened himself with modern art.

I believe that the issue arising from Kontoglou’s work characterizes the state of iconography in Greece and wherever somebody deals with icon painting as a live ecclesiastical tradition. And, due to the significance of icon painting for the development of modern art (and in particular, abstract art), I think that the issue in question does not only concern the Church, but also contemporary civilization.

Gould: Do you have any plans for the future?

J. Xamist: This year, besides painting, I plan to finish my PhD dissertation. I am also organizing a workshop in a Monastery in Barcelona in June. At the end of this year, I have to go back to Chile in order to meet my scholarship obligations, and work there at the University. I would really like to work towards the dissemination of icon painting in Chile, and my dream is to create an institute for the research and learning of ecclesiastical art. In my opinion, icon painting and the ecclesiastical experience that it embodies have a lot to say nowadays. Actually, for me it constitutes an exit from the deadlock of contemporary civilization.

Federico José Xamist’s website can be found here.

Excellent Inspiring Work – great interview !

These icons are stunning–the Transfiguration–I’m not sure I can express… it caught me off guard! It is–immediate. Looking at the Hospitality of Abraham reminded me of cloisonné, between the color saturation and the dimensional play between the background and foreground, if I can say it that way. One lifted the other to me, rather, at me. Such vibrancy to it. I see captured in the pictures posted many “schools” flowed into one another and have become something fresh and unique! I am spiritually enriched through it!

“In my opinion, icon painting and the ecclesiastical experience that it embodies have a lot to say nowadays. Actually, for me it constitutes an exit from the deadlock of contemporary civilization.” This comment embodies pretty much everything I believe about why I make liturgical art. I think that liturgical art is the only answer to contemporary art and culture. I also really love how he frames his discussion of Kontoglou, how Kontoglou’s opening up of the icon can also become a closing down, the same with Ouspensky. It is interesting because we hear a lot of criticism and I myself will sometimes look at some contemporary icons and wonder if they are going too far, even with Kordis, but when we read the kind of prayerful and thoughtful engagement Frederico and Kordis and so many others are putting into their work, we cannot but be hopeful that what will ultimately com out will be for the Glory of God.

Can you offer further clarification on this idea? “I think the natural need to understand how icon painting works is often distorted and cultural and historical facts are confused with theological notions.” An example would be helpful.

Hello Bess. For example, the practice of copying old icons spreads during the sixteenth century in Crete, when the icons production had to meet the demand of Venetians collectors. That it is an historical fact that nowadays has been connected with the notion of tradition (i.e., there are many people who says if you make an icon without copying you are outside of the tradition), whereas the tradition in the case of the icon painting it means other thing. I hope I have been clearer in my point.

Federico Jose contacted me on his trip to Chile and I congratulate him for his studies and iconographic work. I sensed in him great potential and I am pleased to know young people who may be interested in keeping alive a tradition as old and think that it may actually be an answer to our contemporary time.