Similar Posts

Editorial Note: The following paper was presented at the academic theological conference, The Orthodox Christian Seminary in the 21st Century, held Saturday, September 16, during the 75th Anniversary of Holy Trinity Orthodox Seminary, which took place at Jordanville, NY, September 15-17, 2023.[i]

****

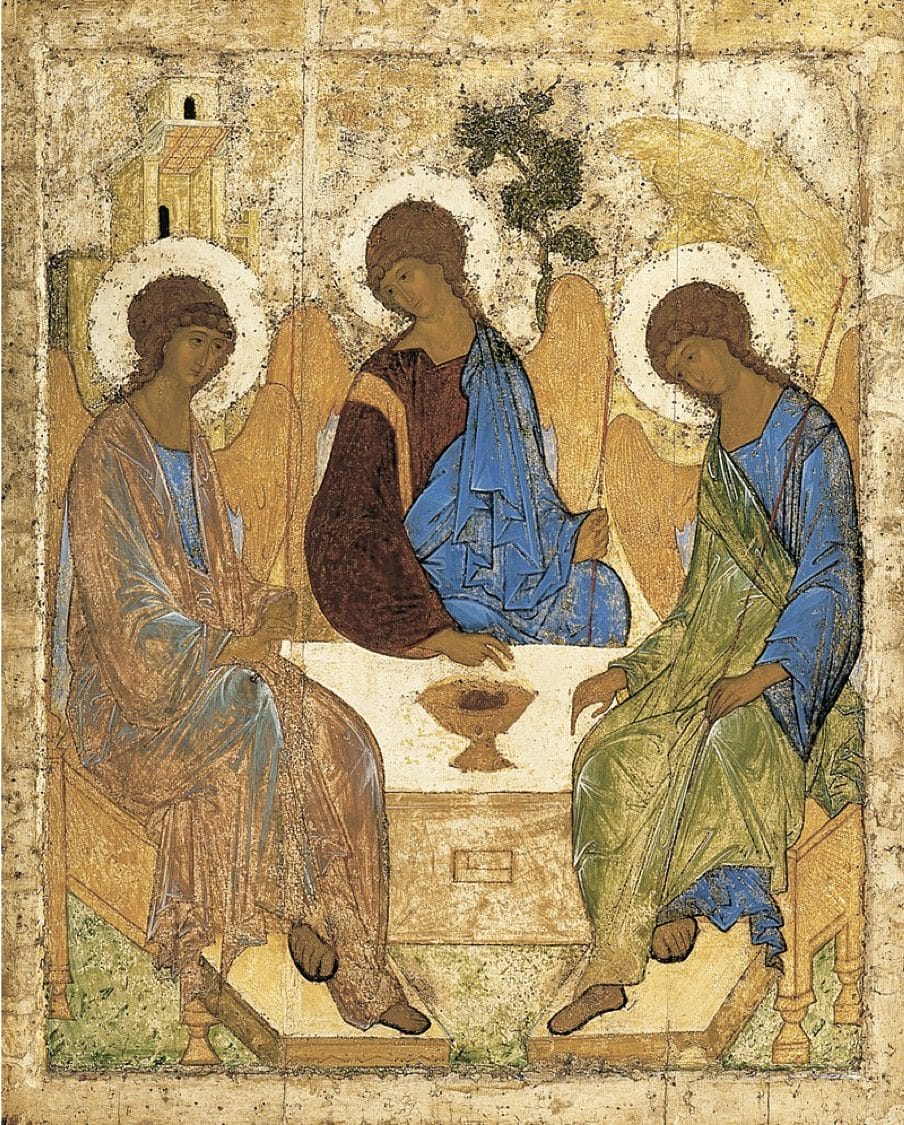

Andrei Rublev, Holy Trinity, 1411 or 1425–27. Egg tempera on wood, 56 in × 45 in. Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, Moscow.

Trinity!! Higher than any being, any divinity, any goodness! Guide of Christians in the wisdom of heaven! Lead us up beyond unknowing and light, up to the farthest, highest peak of mystic scripture, where the mysteries of God’s Word lie simple, absolute and unchangeable in the brilliant darkness of a hidden silence. Amid the deepest shadow they pour overwhelming light on what is most manifest. Amid the wholly unsensed and unseen they completely fill our sightless minds with treasures beyond all beauty.

–St. Dionysios the Areopagite, The Mystical Theology

Intro: From Theology to Art

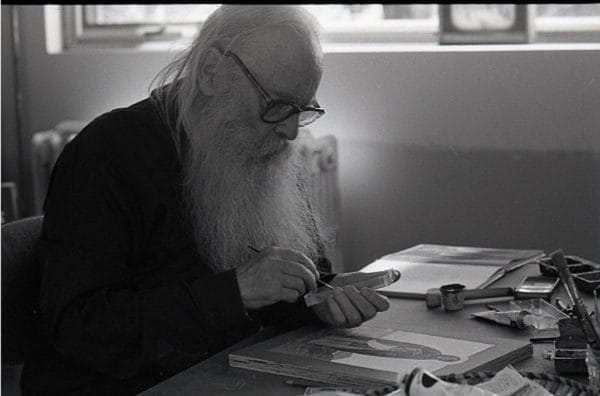

Since we’ve gathered here today to celebrate the 75th anniversary of Holy Trinity Orthodox Seminary, it seems quite appropriate to begin with this doxological invocation of the Holy Trinity. Although not immediately apparent, it actually contains first principles, pertaining to the interrelatedness of theology and art. Hence, as we will soon see, this poem is quite pertinent to our topic: iconography and its integration into a seminary curriculum—something which the eminent iconographer of the Russian Diaspora, Archimandrite Cyprian, recognized by many as a spiritual pillar of the Russian Church Abroad, would’ve found extremely important.

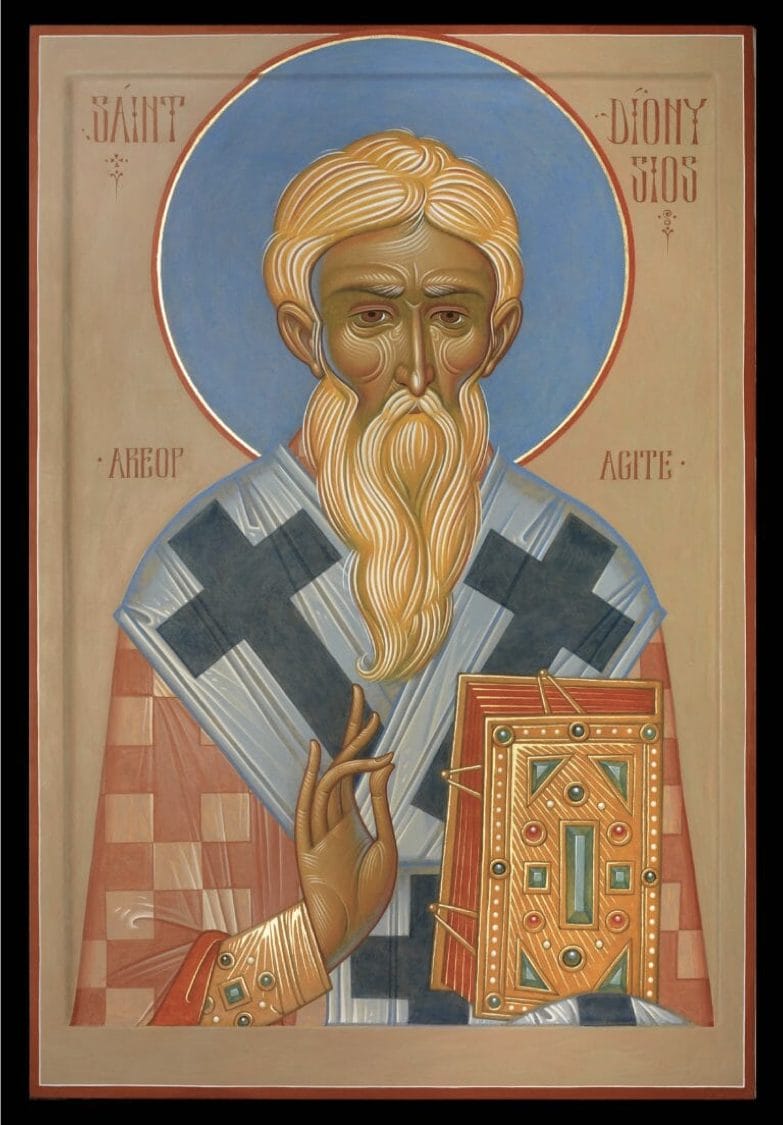

Fr. Silouan Justiniano, St. Dionysios the Areopagite, 2019.

Egg tempera and gold on wood panel, 15 x 22 1/2 in.

This most eloquent and uplifting poem by St. Dionysios the Areopagite serves as the introductory prayer to his famous treatise The Mystical Theology.[ii] The treatise sets out to catechize the reader into the ways of “apophatic” theology, what could only be said negatively about the Godhead— “what God is not.” It uses paradoxical and at times even shocking language, thereby underlining the fact that no conception of the human mind, or anything that can be said positively or “cataphatically,” can ultimately fully encapsulate the ineffable God—He who is beyond being. We come to an experiential knowledge, beyond knowing, through purification and unitive participation in God, not merely by the mastery of abstract speculations or the logical propositions of discursive reason.

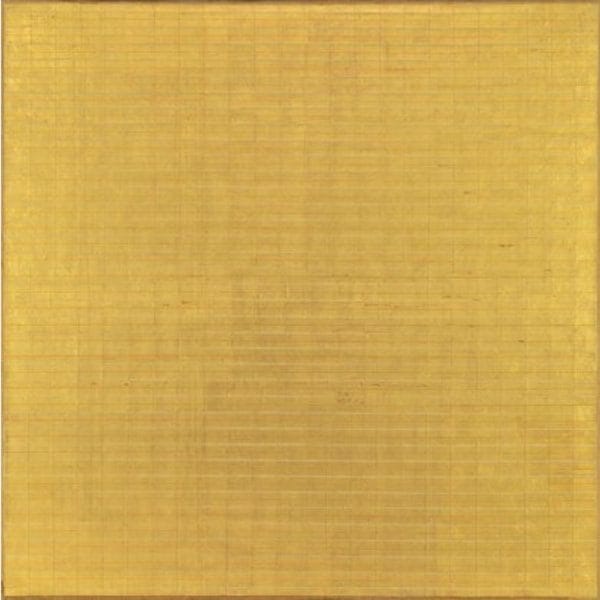

Agnes Martin, Friendship, 1963. Gold leaf and oil on canvas, 6′ 3″ x 6’ 3”. Museum of Modern Art, NY.

Interestingly, although The Mystical Theology focuses on the apophatic mode, it nevertheless still relies on the paradoxical and poetic use of words. Hence there is an inevitable cataphatic component still present, in so far as words and sentences assert themselves as an art form. Poetry, in other words, becomes in itself a positive assertion which points towards, but only takes us to the threshold of silence. Formless silence, beyond thought and poetic expression, would be the entry into the apophatic “brilliant darkness” St. Dionysios speaks of.

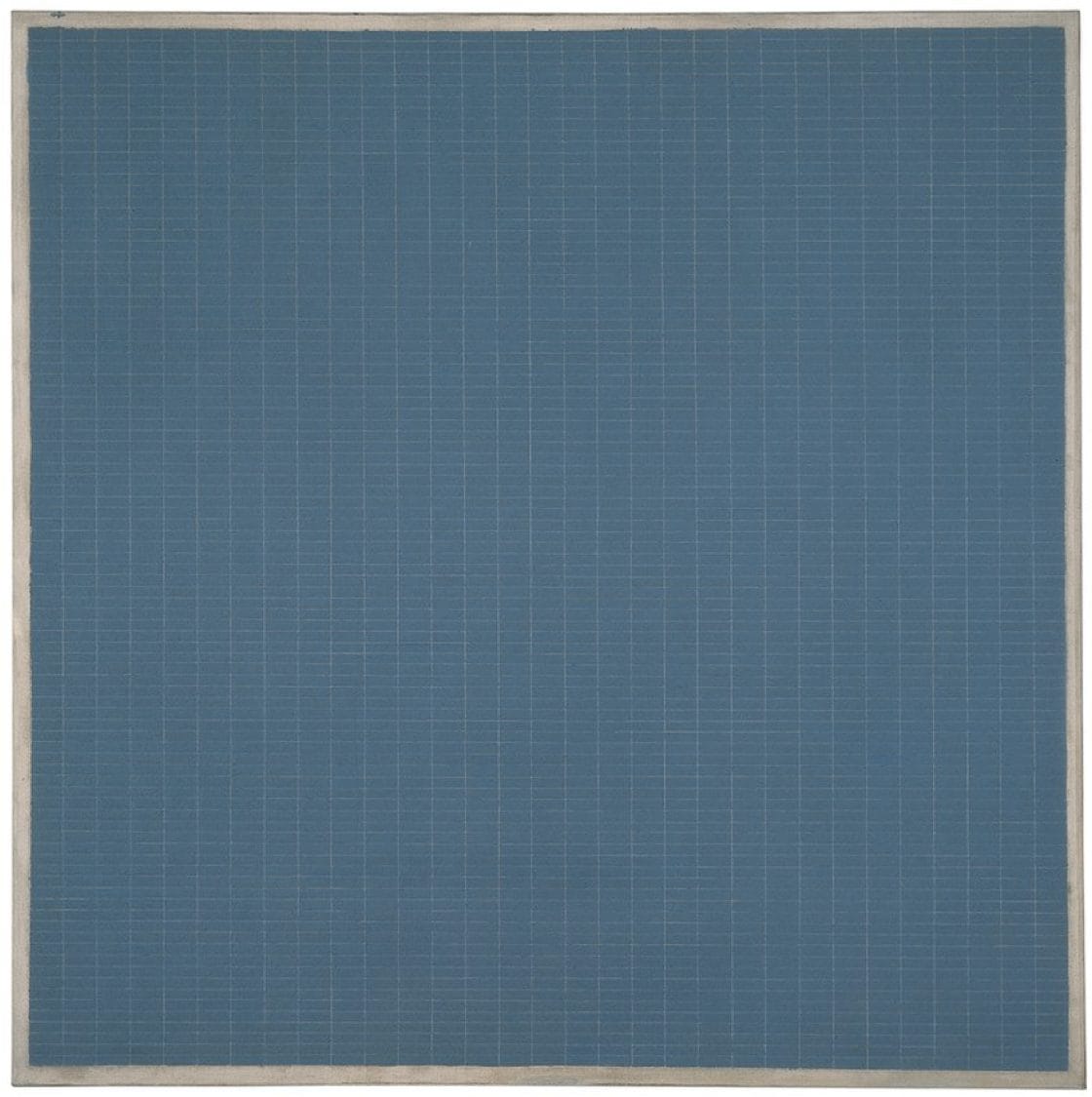

Agnes Martin, Night Sea, 1963. Oil, crayon, and gold leaf on linen,72 × 72 in. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

It would be standing in the presence of God, with the mind in the heart, having attained hesychia—stillness in pure prayer. Meanwhile, however, as we wait for the activity of the Holy Spirit to initiate us into this mystery, we continue to use words in our worship and prayer, we behold icons that uplift us towards the eloquent silence of the Kingdom of Heaven. In short, artistic form serves a crucially important cataphatic role, within the liturgical life of the Church, which complements—without contradicting—the apophatic pursuit of formless prayer.

Therefore, St. Dionysios’s poem reminds us that theology itself is a form of artistic expression, guided by the Holy Spirit. Theology is more than just a bookish and dry, academic science. Just recall how the few who bear the title “theologian” among the saints were indeed extraordinary and prolific poets, such as St. Gregory the Theologian and St. Symeon the New Theologian. The icon painter blends and harmoniously arranges pigments, while the theologian cautiously uses words, as the “matter” which he fashions and transmutes into luminous utterances. At its best, theology becomes doxological, just as St. Dionysios’s poem exemplifies, uplifting us towards the contemplation of ineffable mysteries.

The poem begins with the invocation of the Holy Trinity and it ends with the conjuring up of the word “beauty,” a Beauty surpassing all beauty. It implicitly suggests that the way to be uplifted towards the Holy Trinity is through the radiance of beauty, which serves as a support of contemplative prayer, bursting into doxological exultation. We pass from the immanent manifestation— “what is most manifest”—that is, the earthly instances of beauty, to the uncreated Beauty, which is beyond being. We pass from the aesthetic to that which surpasses all sensation—from the visible, to the invisible.

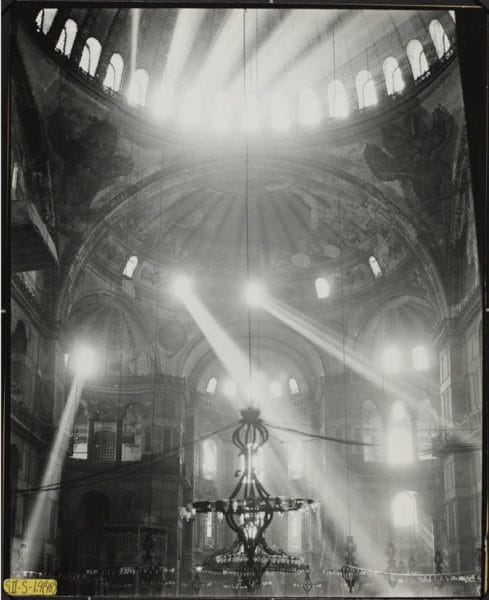

Recall the famous words of the emissaries of Grand Prince Vladimir, uttered upon their return from Hagia Sophia in Constantinople: “…We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendour or such beauty, and we are at a loss how to describe it. We only know that God dwells there among men, and their service is fairer than the ceremonies of other nations. For we cannot forget that beauty.”[iii] In these words, we find encapsulated an Orthodox theology of beauty that echoes the aesthetics of St. Dionysios the Areopagite.

But theology doesn’t function alone. It cooperates with many other art forms, making up the totality of our liturgical arts, and imparting beauty to our services. Among these we find music, hymnography, hagiography, architecture, carving, embroidery, weaving, woodworking, metalsmithing, icon painting, etc. Orthodox worship is ultimately a complete work of art—a great synthesis of the arts—brought together in symphonic harmony. It’s a doxology with deifying transformative power. Raw matter is purified, transfigured through the creative act of man in cooperation with God, thereby becoming a sacramental vehicle, elevating our minds and hearts towards contemplation and participation in the divine nature. Art, in fact, becomes eucharistic. Indeed, the Holy Eucharist itself is the highest and most sublime of the creative acts of man—the Art of arts.

Iconography: Theory and Practice

Just as the theologian crafts words to iconize the invisible, the iconographer’s work is called to manifest in an exemplary manner the beauty of Orthodoxy and its theological depth. Iconography as a visual extension of Orthodox theology is so crucial to our tradition that we even set apart the first Sunday of Great Lent to commemorate the defeat of the heresy of iconoclasm, calling it the Triumph of Orthodoxy. Thereby we underline that there is no Orthodoxy without the veneration of icons. It’s an inextricable component of our Faith. In the icon, being the affirmation of the Incarnation, we have encapsulated the totality of Orthodox theology.

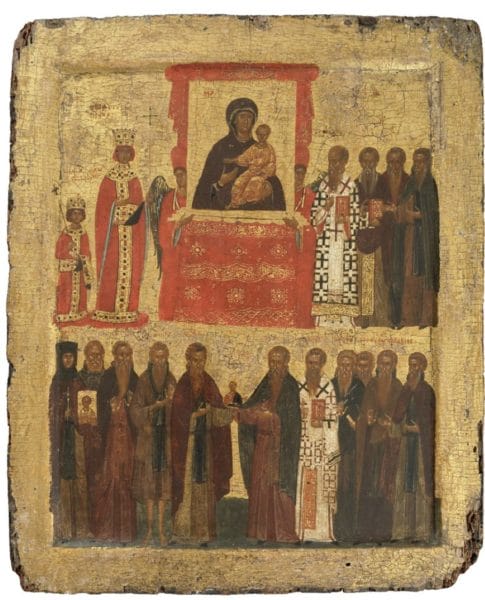

Late 14th century icon illustrating the “Triumph of Orthodoxy” under the Byzantine Empress Theodora and her son Michael III over iconoclasm in 843. National Icon Collection 18, British Museum

Hence there’s no question that the study of iconography should form part of a seminary curriculum, as an indispensable component, whereby our seminarians will be better formed and equipped for future ministry. This education involves both practical and theoretical levels, which I will now touch on briefly. However, let me clarify from the outset: I’m not proposing that all seminarians should take icon painting classes. Nevertheless, although the theoretical level is more pertinent to seminarians seeking future ordination, the practical aspect can’t be ignored. So let me begin with the practical level.

By and large, in seminaries the icon mainly features as a specimen of historical and doctrinal relevance in the study of the Ecumenical Councils and the iconoclastic controversy. Therefore, in a sense the icon remains an abstract book topic stuck in the past, not a matter of contemporary concrete artistic practice. I’ve heard it said that in reality a service could always go on without icons, but not without a good choir. True, painting is clearly not the same. It could be said that musical skills serve an immediate and basic need in worship. But has this become a copout? This view leads to much time and effort being invested into the realm of musical training in seminaries—which should be the case—but rarely any focus being placed on iconography, on the level of practical skills.

It’s indeed ironic, while we speak of the crucial doctrinal importance of the icon, at the end of the day it gets marginalized in priority within the level of higher education in seminaries and the largely artistically illiterate parish context. We would rather continue to purchase cheap reproductions than invest in training and commissioning iconographers to paint icons. Icons are seen as more of a luxury than a need. This problem could be rectified, in my view, by the establishment of icon painting schools integrated into seminary curriculums. This wouldn’t be so far-fetched of an idea to consider here at Jordanville, since it already has an iconography studio facility. Comparable developments are actually currently taking place in two U.S seminaries. But I’ll say more about this shortly.

Turning to the theoretical level, there’s no question that all of us here today uphold tradition, as we should indeed. But, have we simply mistaken this to mean an attitude of insularity? We should be careful with simplistic polemics regarding non-liturgical art and dogmatizing about stylistic matters.

Hence it is generally believed that the ideas circulating today, regarding the theological importance of non-naturalism in traditional icons—often referred to as their “canonical” style—extend back to the Byzantine era. However, we find no prescriptions regarding style documented as part of the proceedings in the 7 th Ecumenical council, in the writings of the iconodule Fathers, such as St. John of Damascus and St. Theodore the Studite, nor in the very few and more recent icon painting manuals that have come down to us. A theology of style, in fact, upholding non-naturalism, began to emerge as part of the icon painting revival of the 20 th century, in the writings of such authors as Pavel Florensky, Leonid Ouspensky, Photis Kontoglou, and others. This theology, moreover, arose within and bears traces of a specific artistic milieu, mainly modern art, wherein movements such as Post-Impressionism and Symbolism, played a major role in the development of abstraction. Furthermore, interest in the icon itself and Byzantinism, within avant-garde movements, would in turn influence the pursuit of abstract art. There was cross-fertilization going on. Thus, ironically, the revival of traditional iconography cannot be isolated from the larger context of 20th century modern art.

Dimitry Stelletsky, The Fox Hunt, 1912. Tempera on board laid on canvas, 27 3/16 x 61 in. D. Stelletsky (1875-1947) is perhaps one of the most underacknowledged contributors to the 20th century icon revival among the Russian emigration in France. He worked as both an icon painter and fine artist. In his work we find a clear example of the convergence between the icon painting tradition and the non-naturalist, primitivist concerns of early modernism. In 1912 the British art critic Roger Fry (1866-1934)—who considered Byzantine art as an important precursor to the avant-garde painting of his day—included Stelletsky in his Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition. It is believed that The Fox Hunt could have been one of Stelletsky’s paintings included in the historic exhibition.

My point is not to undermine the contribution of the pioneers of the icon revival by labeling them “modernists,” but rather to remind us of the fact that the upholding of tradition inevitably involves creative engagement with the immediate needs and challenges of the day. The pioneers did not so much “add to” as “uncovered” or made explicit—as best they could by using a modern aesthetic vocabulary—what was already implicit within the pictorial principles of traditional icon panting. Without this creative engagement there’s no such thing as a living tradition—tradition is creativity. This holds true not only in regards to the theology of the icon, but also to the practice of icon painting itself. Tradition as creativity is what gave us the harmonious artistic synthesis and liturgical beauty of Hagia Sophia, causing those who beheld it to exclaim in wonder, “…we knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth…”

As part of their formation, seminarians need to become aware of the nuances and complexities—just hinted at here—regarding the development of the theology of the icon and its art historical dimensions, which continue to play a role in the theoretical discourse and practice of contemporary icon painting today. There’s no question that iconography directly shapes and theologically orients our immediate worship environment, through the complexities of its aesthetic effect, narrative content, symbolism, and interaction with architecture. Hence iconography shouldn’t be seen as an isolated and marginal practice, in its theoretical and aesthetic concerns, from “more important” practical realities, since it rather plays an integral role within the liturgical life of the Church, whether this be in the realm of private devotion or public worship.

In my view, taking these factors into consideration—as part of a seminary curriculum—will help impart visual literacy and knowledge necessary for future building projects, dispel prevalent misconceptions regarding iconography, and as a whole better equip future priests in their pastoral roles as catechists, in a postmodern society—let’s not forget—unprecedentedly saturated with images. For the preaching of the Gospel entails not only the use of words, but also that of images, through the application of discerning eyes.

Catechesis Challenges

Despite a significant decline in Christianity over the past fifteen years, we have also seen an increase in attendance among young people within more traditional Christian communities. In particular Orthodoxy has reaped a harvest of those hungry for an authentic liturgical life, suffused with beauty and the genuine spirituality of sacramental participation. Among this influx of young inquirers and converts, some are artists looking to place their skills in the service of the Church.

In the past five years or so I’ve noticed a considerable increase in the number of people contacting me on such topics. Some inquire about icon painting classes, while others seek advice on how to best integrate their artistic practice into their Orthodox faith. And others still, who are not yet Orthodox, ask me for assistance with their graduate thesis projects. The common thread that unites them all is the power of the icon. Icon painting has in some mysterious way spoken directly to their hearts, imparted meaning and inspired them. Hence a seminary that better integrates the study of iconography into its curriculum, will better equip future pastors to deal with this kind of challenge.

Possibilities in Curriculum Development

But, the question remains: how do we integrate the study of iconography into a seminary curriculum?

Allow me to return to the important distinction between the practical and theoretical aspects of icon painting, discussed earlier. Hence, on the practical side, we’re talking of the imparting of skills, the teaching of iconography as a studio practice, through the opening of an icon painting school. On the theoretical side, we’re dealing with the teaching of the theology of the icon and its aesthetic theory, along with the inextricable component of art history. These are the two components that could be integrated into a seminary curriculum, the first in a more limited sense than the later. But the theoretical level is the point of overlap between these two—the means of integration.

I say that the practical aspect would be more limited, since it’s clear that not all seminarians are meant to be iconographers. So, as mentioned in the beginning, I’m not advocating for mandatory icon painting classes for all seminarians as part of their curriculum. Nevertheless, if there was an icon painting school attached to the seminary, seminarians interested in taking an icon painting class should have the capacity to do so, as an enhancing part of their education. So, even if seminarians don’t take painting classes, having accessibility to an icon painting studio would be intellectually and spiritually beneficial to the students. Jordanville, as we know, already has an icon painting studio, which could serve as the facilities for an icon painting school attached to the monastery. Courses in the icon painting school could be designed as a two-year, graduate program, for proficient students with previous artistic training.

Although the opening of an icon painting school would be geared primarily for the training of future iconographers, rather than seminarians in pursuit of ordination, its integration to the seminary curriculum would be, as just stated, through the theoretical courses—the theology of the icon and art history—which should indeed be required for all seminarians. Some of the topics which would be beneficial to include in the theoretical courses would be: Church architecture and Iconography; an overview of Byzantine art, from late antiquity to the Renaissance; Russian art from the medieval to the modern period; art from the Renaissance to the 19th century; movements of modern art; readings in the theology of the icon; the 20th century icon painting revival, etc. These topics are only suggestions, but they give you a sense of the range of possibilities to draw from, in refining a suitable course of study, for both future iconographers and seminarians. It seems to me that, even if opening an icon painting school is not a viable option at the moment, the theoretical course of study can be more readily implemented.

Recent Developments

As I mentioned earlier, we are actually seeing some promising steps being taken, in U.S. Orthodox seminaries, towards the integration of iconography into a seminary curriculum, both in the practical and theoretical levels. These are good steps forward, since in spite of all the increase in the popularity of iconography over the last few decades, no substantive, practical and professional icon painting programs have been established in the U.S.

What has become prominent, however, is the one-week icon workshop phenomenon, often initiated by itinerant iconographers themselves. These workshops are generally aimed for the amateur consumer and don’t function as a sustained curriculum, intended to properly train serious students towards a professional level. Their approach tends to misrepresent the practice of icon painting, turning it into a paint by numbers hobbyist procedure. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, however, an alternative model has emerged, with more of an in-depth approach, in the form of online iconography programs being made accessible internationally.

In the anglophone sphere, although not seminary affiliated, there’s the post-graduate three-year part-time icon painting program in England, founded and run by the prominent iconographer Aidan Hart, under the auspices of The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts. The program offers a methodically taught foundation for people wishing to develop their skills, emphasizing the importance of integrating theoretical study with practical education. It’s among the most in-depth icon painting programs available in English, but does not aim to teach students to a full professional standard. Students who complete the program receive a ‘Certificate of Completion” from the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts. This program can perhaps serve as a possible model towards a more rigorous level of training for iconographers in a seminary context.

Returning to U.S. seminaries, an important development is that the Monastery of St. Tikhon of Zadonsk, affiliated with St. Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, recently broke ground on the building of a new icon painting school. They hope to open in the fall of this year, with two professional iconographers from Belarus, Anton and Ekaterina Daineko, coming to lead the teaching, along with the local iconographer Ivan Roumiantsev. The program is for more advanced artists and only four will be chosen for their pilot program. This could end up being the first stationary icon painting school in the U.S. on the grounds of, and affiliated with, a seminary. It still remains to be seen, however, how the course is structured, whether or not the practical training of iconographers will be directly integrated into the seminary curriculum, through the theoretical course of studies.

Another recent development is the establishment of the Institute of Sacred Arts, directed by Peter C. Bouteneff, at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary. The institute focuses on exploring the mutual relationship between theology and the arts—whether this be icons, music, architecture, homiletics or liturgics—from an academic perspective. The renown iconographer George Kordis is one of their affiliated scholars and served as their first artist in residence last year. This connection has proven to be fruitful, since St. Vladimirs is now collaborating in partnership with Kordis, by implementing a curriculum he developed for his online Writing the Light iconography program. It’s a two-year, low residency certificate program, which doesn’t count towards academic credit with St. Vladimir’s Seminary. It incorporates online classes (live and prerecorded) and residencies in Greece, Romania and the USA. In other word, it looks like the Institute of Sacred Arts, while mainly focusing on the theoretical study of theology and the arts, is making accessible some practical components as a secondary part of their program.

Another recent development is the establishment of the Institute of Sacred Arts, directed by Peter C. Bouteneff, at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary. The institute focuses on exploring the mutual relationship between theology and the arts—whether this be icons, music, architecture, homiletics or liturgics—from an academic perspective. The renown iconographer George Kordis is one of their affiliated scholars and served as their first artist in residence last year. This connection has proven to be fruitful, since St. Vladimirs is now collaborating in partnership with Kordis, by implementing a curriculum he developed for his online Writing the Light iconography program. It’s a two-year, low residency certificate program, which doesn’t count towards academic credit with St. Vladimir’s Seminary. It incorporates online classes (live and prerecorded) and residencies in Greece, Romania and the USA. In other word, it looks like the Institute of Sacred Arts, while mainly focusing on the theoretical study of theology and the arts, is making accessible some practical components as a secondary part of their program.

Conclusion

In conclusion, whether it be implemented on a practical or theoretical level, what would be the benefit of integrating iconography into a seminary curriculum? First, as mentioned earlier, it would be of great help in dispelling misconceptions about icons and imparting visual literacy. Second, it would impart knowledge about the symbolic meaning of the temple compartments, how the iconographic program functions within the architectural space of a church. This is very important, since many future priests will be called to build a church and they must know the basics about the ordering of an iconographic program. Third, the theology of icons provides the clergy with great material for preaching and catechism, so elementary knowledge about icon painting could be very useful for catechizing parish congregations.

Thus, whether it be in the study of the theory or practice of iconography, Holy Trinity Orthodox Seminary could play a constructive role in tackling and overcoming some of the real challenges and needs just briefly delineated here. It has the potential to contribute towards the nourishment of the living tradition of theology as art and iconography as theology. This is something that, in my view, Archimandrite Cyprian would be pleased with, as one of the foremost master iconographers of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. For it would be in continuity with the spirit of his frescoes, which are nothing other than pictorial doxologies, in eloquent exaltation of the Holy Trinity—colors reflecting the radiance of Beauty beyond being.

Notes:

[i] I would like to extend my deep gratitude to Nicolas Schidlovsky, Dean of Holy Trinity Orthodox Seminary, for giving me the honor and privilege of presenting this paper at the 75th Anniversary symposium. This paper is also greatly indebted in many ways to the support and encouragement extended to me by Joachim Pissarro, Professor Emeritus of Art History, Hunter College of the City University of New York. Moreover, the writing of this paper would not have been possible without the very helpful feedback I received from Philip Davydov, Monk Elias, Aidan Hart, George Kordis, and Todor Mitrovic. Any errors and misconceptions contained in the text are mine, not theirs.

[ii] Pseudo-Dionysius: Complete Works, ed. Paul Rorem (New York, 1987), pp. 133-141.

[iii] The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text, trans. & ed. by Samuel Hazzard Cross & Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor (Cambridge, MA, 1953), p. 111.

Some very interesting points and formulations for future development of Iconography within and/or alongside the studies of ordinands. I was interested in the reference to knowledge and appreciation of the Liturgical space within churches – how these are part of history and tradition and also of their subliminal and mystical influence upon the worship and worshipper within an Orthodox church. Further information of this would be of interest.

Could you explain why you included two paintings by Agnes Martin?

Do you think that iconographers (laity) should have some theological training?

Thank you for a very interesting article.

Your question about Agnes Martin is very good.

I included her work because it can be seen as a kind of pictorial apophaticism. Her paintings are perhaps the closest you can get to formlessness while still implementing form. The paintings depict no-thing. But no-thing is not merely nothing, but rather a clearing that makes manifest presence. Hence they parallel the way text is used in St. Dionysios’s Mystical Theology, which in its negation of concepts takes us to the threshold of knowledge beyond knowing. In their stillness they invite contemplation and remind us of the silence of formless and pure prayer.

Yes, I think iconographers (laity) should have some theological training. It’s an inevitable necessity of any Christian, in particular those who will be dealing with the visual embodiment of the Church’s teaching. But this should not be taken to mean that all should be scholars or professional academics. There are different kinds of training, different paths for different people.

Yes, there’s the seminary path for those called to it, but theological training is also to be readily found through regularly, prayerfully and watchfully, attending Church services, which are saturated with scriptural exegesis and doctrinal formulations. “The one who prays is a theologian; the one who is a theologian, prays.” Thus, prayer, church attendance, partaking of Communion, ascetic effort, reading the Scriptures and the writings of the Fathers, becomes the most accessible school of theological training—for every Christian.

In short, all Christians should have at least some rudimentary theological knowledge, accompanied, of course, with a virtuous way of life. Without these we fall prey to ignorance, the passions, doctrinal error and heresy, which ultimately lead to perdition.

We believe that our orthodox faith church and mystical powers of our Lord are indivisible from one another. No human logic can grasp the Glory and Majesty of our God. In my humble opinion our Master and Creator designed it this way. When we apply our Love to Our Lord through art and writing of icons perhaps on some small level and through the Grace of The Holy Spirit we can connect to our Creator.

Thank you, Fr Silouan, for your as always perceptive and balanced presentation of a nuanced and vital field. Indeed, integrating schools of iconography with seminaries would root icon training more firmly within the Church. Might I just add that within seminaries there is an equally important field that I believe needs to be introduced, as mandatory for all seminarians, and that is the principles and skills involved in commissioning work. While most seminarians will not be iconographers, they will all as priests end up overseeing new iconography and church building. To do this well they will need to know what characteristics to look for when seeking designers and makers, and then possess the skills and know the theological and aesthetic principles needed to brief them properly.

Thank you, Aidan!

You make a very important point.

I completely agree.