Similar Posts

Interview with iconographers Philip Davydov and Olga Shalamova by Irina Yazykova (2010) and Andrew Gould (2014)

Philip Davydov and Olga Shalamova are based in Saint Petersburg and are well-known iconographers throughout Russia and abroad. They participate in round tables and conferences, teach iconography and monumental painting, and promote the revival of iconography.

Irina Yazykova: What do you think is so special about the Sacred Murals Studio, apart from the fact that it is run by a family couple?

Philip Davydov: I think we are behind the times. The atmosphere of the epoque when my father and his friends started to paint icons in the USSR was significantly different from what it is like today. If we speak about that time, the beginning of 1980s, the iconographers were all more idealistic than practical. At that time any Christian art in the Soviet Union was considered “religious propaganda”, and artists could have been punished for painting an icon as for committing a crime. But those who were attracted to icons at that time knew clearly that medieval icons have to be studied as spiritual and cultural treasures, that every icon needs plenty of time for realization, with torments and throes of creation. My father used to work this way for a long time, and maybe I just inherited this way of working from him.

I think this approach is the only permissible one for an image created for contemplation in prayer. It must be slowly planted and cultivated, and at the same time we have to avoid any confusing complexity… Let’s compare this process with serious book writing – you have to be spiritual and wise so your icon may be also.

Irina Yazykova: So, should it mature first, before it is completed?

Philip Davydov: I think yes. I have heard many iconographers say that when they begin painting an icon they do no know what it is going to look like at the end. I am not sure it’s the right way, but I think it is important that there is some research.

Irina Yazykova: Your are a second generation iconographer, – I know that first you studied and worked with your father. This seems very interesting. Now lots of people speak about the gap with tradition, having started their path without any teacher. In your case we can start talking about a kind of tradition. We know, that being translated from greek, this word also means something like “communicate” and “transfer”. So, – was there any transmission, at least in the very beginning?

Philip Davydov: Absolutely! I am endlessly grateful to my father for the discoveries he made with his like-minded friends. For them iconography was not a way to earn money. In soviet times they could not even imagine it as a profession. It was a devotional hobby which could take all of your time and give you some possibilities for creativity in the church. Now everything is different in Russia, and iconographers think much more of making money. Of course, I can understand – there are dozens of newly built churches, and the priests want icons and all the other utensils to be as affordable as possible and to be produced as quickly as possible. I just can’t produce my icons or frescoes in such a way.

Irina Yazykova: Then I want to ask you a question about education: you teach in the Orthodox Institute of Theology and Sacred Arts in Saint Petersburg, organize courses and seminars in Russia, Australia, Canada, and USA. What would you like to tell your students?

Philip Davydov: First of all, I would say iconography should be considered a thoughtful deed. Let me repeat it once more, – we can not write a good book just on the spot, easily and quickly. We should not get fascinated with our first successful results: “Wow, I have painted an ideally straight line by hand!”. Apart from the professional skills, an iconographer should posess the spiritual harmony and integrity, lay oneself out to be true Christian. Then iconography is no more pure craftsmenship or art, but true theology in colors.

Irina Yazykova: What about your and Olga’s education as professional art historians and art-critics, – does it help your work in icon-painting or you feel it as a useless burden?

Philip Davydov: We met when we studied together. No, it does not bother, on the contrary – it helps a lot. On one hand, the art-history and art-theory education is a great weight (of knowledge); on the other hand, it is a great plus.

When for six years you are loaded with the best of texts and visuals, the best classics of architecture, sculpture, and images of all times, you get used to it. After this kind of treatment, whatever you see or read (your own work and the world around), you unconsciously compare with best examples you remember and immediately see and feel what is false or wrong. And at the same time you feel much more painfully and immediately the gap between what you want to do and what you really can do.

In our days this is even more notable. Everyone is striving to do his or her best; this “best” can be very different. We may master our skills and technique, or we may try to communicate something very important (if any), and these are two different ways. Comparing twelfth-century Constantinople icons with nineteenth-century Russian provincial icons would demonstrate an unbelievable diversity, but the same goal – to make an icon be an image of God and a window to heaven, but not a decorative object.

Irina Yazykova: Some years ago you organized an Iconography Symposium in Saint Petersburg, – what was your main purpose – why did you make it happen?

Philip Davydov: I am not totally happy with what was done, I still think we might have organized it better. Anyhow the main mission is accomplished – to show our students that there is an uncountable number of different ways and paths in iconography, and they are all natural branches of the tradition. We can’t judge which one is better or worse. That’s what we wanted to accentuate at the Symposium. The year before I was invited to participate a similar event in Romania (Iasi). The most imressive thing for me was the diversity. In Russia we have very few examples of medieval monumental church murals. Theofan the Greek worked in Novgorod, Andrey Rublev in Vladimir, Dionisy in Ferapontovo… After that time we have carpet-like murals in Yaroslavl, which should be always viewed only in strong relation with their historical context. The same can be said about the iconography, – a very fragmented heritage, thousands of churches destroyed in soviet times. But when we were in Romania, we were brought to an excursion and we saw it – every little district of Romania has dozens of painted churches (inside and outside). When Russian iconographers study, they used to pick up details for their images from this or that concrete model. But in Romania there are hundreds, not to say thousands. That is why they have the freedom we are missing.

Irina Yazykova: Question to Olga. What was first for you, – to be an art critic or an artist?

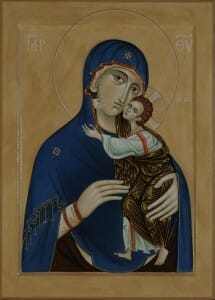

The Mother of God Enthroned with Christ Child by Olga Shalamova (2013), detail.

Olga Shalamova: I started as an artist, but at a certain point I understood that to continue this path is going to be a very hard task. So I enrolled at Fine Art Academy, faculty of Theory and History of Art.

Irina Yazykova: What about now, – do you continue the path of an artist? You paint icons, don’t you?

Olga Shalamova: Yes, it was Philip who returned me back to the art and I saw it could be natural part of my life.

Irina Yazykova: Is it right to say that you are an artist and art critic at the same time? Usually artists do not like art critics.

Olga Shalamova: I do not know what to say. I think both my professions just help to each other. And first of all, an art critic helps the artist.

Irina Yazykova: Would you agree that very often an artist just stops in development, when he or she stops thinking and analyzing?

Olga Shalamova: Yes, education in art-theory and art history gives endless possibilities for an artist and for development. Painting an icon is a constant creative research and a serious thoughtful work. And even so, at the end, when everything is finished, you understand that you did not reach what you wanted.

Irina Yazykova: What about the knowledge of the tradition, it’s depth, – does it disturb you at all? Understanding the beauty of Rublev’s icons, the frescoes of Dionisius, – can this be like brakes for the working process?

Olga Shalamova: For me it does not work like the brakes. I am not a kind of a person who can make copies. I am just unable to do it. Even if someone would really command me to copy exactly, even then I would not be able. Yet in my childhood, painting a still life in art school, I always ‘moved’ all its components to make them fit better.

Irina Yazykova: What you think is the most important in iconography?

Olga Shalamova: It is hard to identify one most important concept. I think in painting an icon everything is important and nothing is secondary.

The Mother of God with Christ Child by Olga Shalamova (2014)

Irina Yazykova: Then how you can distinguish that the image comes out well? Is it intuitively?

Olga Shalamova: I never think it came out well. I just work and in greater or lesser extent out comes what I concieved. Well, sometimes it does happen, – when you have just finished an icon and look at it for the first couple of days. You consider it to be a good job and yourself to be a good master for a while. But then comes another day and you understand it’s not true.

Irina Yazykova: And it’s time you have to hand over your work to the client?

Olga Shalamova: No, even that is not a problem. I understand that this concrete work is finished and it does not get better if I start changing it. It means I have to start a new one and pay particular attention to the issues experienced in the previous one.

Irina Yazykova: Now I would like to ask you a question as I would ask an art critic. You study russian iconography of the soviet period, – not the classics, nor the contemporary. What is so special in it, does it attract you as an artist?

Olga Shalamova: First of all I would like to preserve the memory of these people, who worked in iconography in such a difficult time. In 10-15 years it will be impossible to gather any material about them. The generation of those who might have known these people is passing away. The icons painted in the soviet period from time to time get substituted with newer ones, are burned or even thrown away by the churches. And this is going to be truly a shame, because then we will have a distorted picture of iconography in soviet times. Even now we know almost no one, except for Juliania Sokolova. Of course, we can’t say that all iconographers of her time were the most genious of all times, but it is important to know what kind of people they were. Why did they do it? What was their contribution for the development of iconography, and who were their students? Learning more about them we understand that these are our roots. And without knowing our own roots and the history we can not understand what is going on now.

Irina Yazykova: You have a son, do you want him to become an iconographer?

Olga Shalamova: I cannot want anything instead of my son. If he wants to do it we will be glad and will help him with pleasure. If he chooses some other way we will try to help him as well.

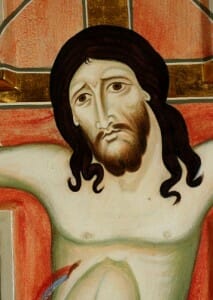

Christ. Detail of a Crucifix by Philip Davydov (2013)

Irina Yazykova: Does he show any interest in art, in iconography?

Olga Shalamova: He loved painting much better before he started to go to school. At that time he had enough time for the creativity and self-expression. But I take it easy, I think we should not adjust children for our interests. If it will be interesting for him, he will always have possibilities. But if not – not.

Irina Yazykova: Is it difficult or easy to work side by side with a husband-iconographer?

Olga Shalamova: I consider it as a very positive fact, because there is always a possibility to ask for advice, to discuss, and I think it’s cool. We always feel like being in working process, not only with a paint-brush in hand, but also doing some routine domestic work. And this is very important, because the thinking process has an enormous significance in iconography.

2010, Saint Petersburg

Andrew Gould: How did you master icon painting? What was your training like and how many years did it take?

Philip Davydov: During my last school years and afterwards I used to help to my father, an orthodox priest and iconographer who started his mission in 1980s.

Parallel to the work in my father’s studio, I graduated from Fine Art Academic Institute in Saint Petersburg (my thesis being, “Genesis and Evolution of Altar Panels in Medieval Italy”). There I met Olga, who by that time graduated in an art school and art lyceum, and worked in the museum of the Academy of Fine Arts and Russian Museum.

I would say that my mastering process was very difficult and tormenting. When I worked with my father I learned a lot about preparation and secondary work, like gessoing, mixing pigments, gilding, and other necessary skills. Of course I was doing a lot of drawings and painted some icons with my father’s guidance. Then I probably did not understand what was so special about sacred art and how exactly the study should go.

Starting our own studio in 2001 was also not easy because only then I discovered that iconography had so many requirement (as from the point of view of the visual language, the point of view of theology, correspondence with the tradition, and many other things). At the same time I was thrilled that all these requirements and rules helped us to follow some certain road – the limits helped us to grow.

Now I think that the iconographer has, so to say, a double task. He (or she) has to learn both – the literacy of the secular art, and the 2000-year tradition of Christian art. It’s much the same as the church fathers did in their time in the verbal sphere – learning rhetorics and other professional disciplines.

Iconographers of our days need both of these spheres because now we live in an open world, – our images also have to be open. Our icons and frescoes are viewed by our contemporaries, who will only appreciate what we do if it’s done professionally. At the same time we have to be faithful to the spiritual treasures of the tradition, because only with this nutrition we can do something worthy.

I do not know how many years it would require to become a good iconographer. I may say like 10 years, but maybe there are some natural geniuses who can do something great right on the spot. I hope I am still learning and growing, hope my next icon will be better than my previous, and the future may also bring even better fruit.

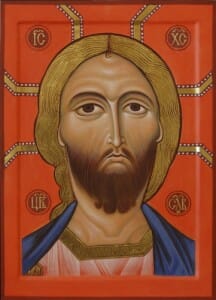

The Mother of God with Christ Child by Philip Davydov (2014)

Andrew Gould: What specific materials and techniques do you use? Is there a practical or artistic reason that you use them?

Philip Davydov: Usually we paint with natural pigments, using egg tempera on gessoed solid wood panels, recently we started to work with relief gesso.

Here is a description of my techniques:

Egg-tempera

I have learned this technique from my father and yet continue to master it, because I think it has some particular qualities, necessary for the liturgical art.

First, – because it can give limitless hues and tones even in a very limited palette of natural pigments.

Second – I consider egg tempera to be perfect media for icons, because it marvelously renders the bi-dimensionality if we don’t want to make our images look realistic. The pigments themselves can be very simple and cheap, but the texture they make with the egg tempera makes a perfect balance between their natural beauty and the level of conventionalization necessary for iconography.

Third – because the egg tempera gives the possibility to create unbelievably deep and transparent glazes and shades, – the smoothest transitions with unbeatable lightness.

By now I have used this technique for almost 20 years, and in every image it still reveals to me some secrets, – first of all in how beautifully it renders the colors, if applied with care.

In short, the icon-painting process can be divided in 4 stages:

1. Drawing (underpainting)

2. Painting (applying the local colors)

3. Accenting (applying highlights and shadows)

4. Graphics (drawing lines, halo, letters and other concise details)

As in drawing, and in the glazes, dealing with almost any consistency of the paint, we have learned that the paintbrush should always be dry enough to apply a very thin layer of color. This gives the freedom to adjust the painting process in hundreds of different ways, manipulating with almost transparent shades and modeling forms and shapes.

Relief Gesso

Olga Shalamova: From the earliest times iconographers decorated their icons in different ways. Maybe the most popular was the gold with all types of incising on it. The most famous icons were covered with gilded or silvered rizas with all sorrts of precious stones and pearls.

If we consider the situation of our time, a great number of these decoration techniques, (especially gilding), have lost their meaning. This happens because in our everyday life there are so many gold-imitating materials, from bijouterie to the “golden” spray paint from a dollar store.

The gold on a contemporary icon is no longer perceived as an expression of absolute value. Now we think or cogitate, rather than just see, that it is an image of Light of God.

This means that it’s better to add our labor instead of gold if we really want to add more value to our icons. So, the technique of the relief gesso gives almost infinite possibilities for this kind of elaboration. Hand-crafted backgrounds, halos and ornamentation, help to stop the beholder’s wandering view and underline the significance of the image.

In our days, with technologies in all spheres of human activity (including iconography), reaching such an incredible height, I think at least in the icons it is very important to preserve the sensation that the image was really made by a human hand.

On the other hand, there is nothing really new in this technique, since we can see it widely exploited in 12th and 13th century Cypriot icons, in Russia, and in some other places. Artists were not just modeling the relief backgrounds, sometimes they even carved them. While studying the Byzantine tradition of relief icons, I decided to model some icons with gesso. I liked that idea because I discovered that when we start simplifying the image, transforming it into a relief, it’s main sense and idea gets much easier to perceive for the beholder.

Andrew Gould: Which historical styles of iconography are you most attracted to, and how would you characterize their influence on your work?

Philip Davydov: I would say that I probably love best the Byzantine art from between the 12th and 14th centuries, but I have no preferred style. When I look for the models, preparing to make certain icon, I am trying to find any image and sculpture which would help me to make my image as essential as possible. Searching through my library and on the internet, I am looking for the ideas and not for specific stylistic details. The main difficulty is to find the harmony and the balance, because the amount of information should be very well measured to be comprehensive. I love the simplicity of Romanesque images, but I can hardly tame their dynamics and distortions. During the last couple of years more and more often I value the early Christian images and get inspired with their immediacy.

Andrew Gould: Do you see your work as belonging to a particular style, or do you see your work as something new and unique within the tradition?

Philip Davydov: Style is a way of life; it is not a glove which you can pull and remove. Even if I would declare my work as “byzantine style”, it can never be real byzantine, because the gap is measured in hundreds of years. It would be much more real if I say that we studied the principles of Byzantine art. And doing it properly, we came to a thought that it would not be appropriate to reproduce icons exactly as they were made, belonging to their time and their circumstances. Learning from Byzantine artists helps to understand certain principles and methods, so working knowingly we can correctly cooperate with our predecessors; then the modified models fit our concrete tasks.

Andrew Gould: Does your particular style of painting reflect any particular beliefs about the church nowadays and what it needs?

Philip Davydov: Thank you very much for this question. I believe, that icons and frescoes of our time first of all should be just painted consciously. If from the very beginning, while only starting to plan future image we will pay attention to it’s future context and role in the environment, our prayers and meditations may help us to make it contemporary without any particular quirks. Otherwise, if we think of an icon as of an autonomous sacred object which has to be “cloned” from it’s medieval prototype, it may come out very similar to the model, but it will not be addressed to our neighbor.

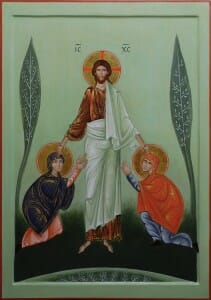

Nativity of Christ by Olga Shalamova (2013)

Andrew Gould: How would you characterize the state of icon painting in Russia today? Are you pleased with most work done nowadays in your country, or do your think anything has gone astray?

Philip Davydov: There are hundreds of churches built in Russia in last two decades. But in most of the cases, even building new churches and painting icons for them, most architects, iconographers, and priests who commission their work, do their best to do everything exactly as it used to be in the past, – in 17th, 14th, or some other century. Leonid Ouspensky, Grigory Krug, Joanna Reitlenger, and similar masters, are considered to be outsiders and individualists, breaking canons and dangerous for the church. Instead, those who paint “exactly like” Rublev and Dionisy are in a great favor now. For me this is a sad thing, because I remember my father’s colleagues gathering in 1990s; they were dreaming about revival of spirit, not form.

2014, Saint Petersburg

Editors Note: Philip and Olga are currently preparing an exhibition of their work in the USA. It will open at Wesley Seminary (4500 Massachusetts avenue, Washington DC) on June 17th, 2014, and last until September 20th, 2014 (August 1-21 closed for technical maintenance).

Artist’s talks are scheduled for 4:30 pm July 15th and midday August 16th.

The interview of Irina Yazykova with Philip Davydov and Olga Shalamova was originally published in Russian at http://www.art-sobor.ru/archives/1237

The website of Sacred Murals Studio is www.sacredmurals.com

Icons: Not simply windows of transfigured time and space but also the means by which we participate in the actions of the Divine Energies. In the Light of Pascha, we behold the actualisation of both spirit and form.

Of course, dear Steven! Thank you very much.

With warmest regards,

Philip

Most welcome Philip. Christos Anesti! Have you thought of reaching out to the Syrian Greek Catholic community? I have it on good authority that the 91 churches destroyed in the civil war are being rebuilt. Yes 91!

“…they were dreaming of revival of spirit, not form.” How true that is! I feel the biggest challenge facing iconography today is precisely this irrationally conservative and ignorant attachment to forms that were relevant to a certain culture at a certain time, while we ignore our own cultures and times, fragmented as they may be.

Thank you for this article.

fascinated by the article Thank you both. Very struck by the idea of relief gesso. Many possibilities there , so much to think on , so much