Similar Posts

I have recently completed a small but highly interesting project, two years in the making, and involving several master artisans. It is a wooden cross with carved stone icons, crafted like a jewel, wholly traditional, and yet quite unlike anything seen before.

This is one of those projects that grew, perhaps providentially, from an initially simple commission. The client wished for Jonathan Pageau to carve an iconographic cross from stone to hang on the wall. But a stone cross is fragile, so we considered how to frame it. As the frame became more elaborate, I suggested the cross ought to have a more prominent liturgical function. Ultimately we decided to make two bases for it – one that allows it to stand on a table for veneration, and another, a tall shaft, that allows it to be used as a processional cross. It is intended to be a companion piece to a gospel book we made for the same client.

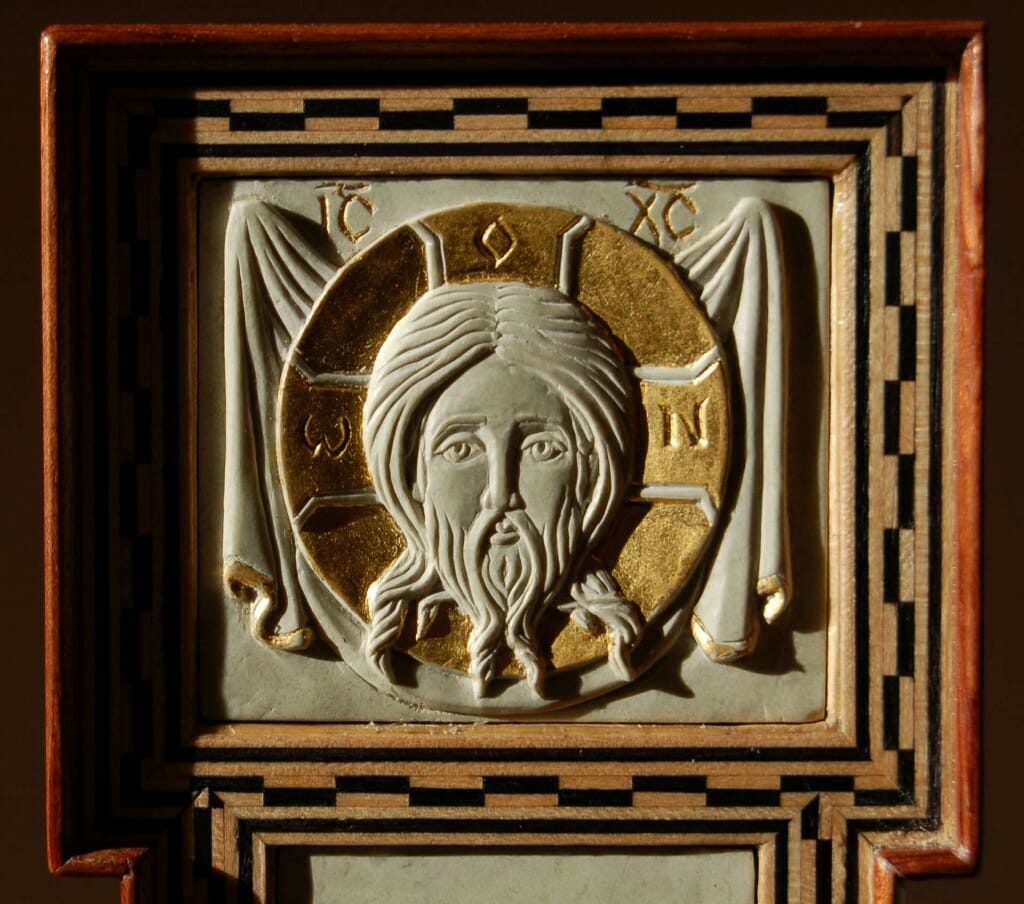

I began by designing all the parts, and sent templates to Jonathan. He carved the four icons in steatite, a fine stone from Africa that was used to carve icons in ancient Byzantine times. He also gilded certain details, which considerably increases the material beauty of the carving. I crafted the wooden frame, edging it in African rosewood and inlaying the front and sides with marquetry banding. Finally I designed the turned base, processional shaft, and matching candlesticks, and had them made by a master wood-turner. These parts are made from instrument-grade American curly maple and walnut. I ebonized the walnut with ferrous sulfate solution and finished all the woodwork with shellac and wax.

Thus this work is a collaboration among four artists: myself, the designer and woodworker; Jonathan Pageau, the carver; Lee Henson, maker of the marquetry banding; and Ashley Harwood, master turner.

Stylistically, this project draws from several traditional sources to synthesize what might be considered a new style. The use of inlay in Orthodox woodwork became prevalent in Greece in the 17th century. There are many fine doors and other furnishings on Mt. Athos that include inlay banding, and there is the spectacular example of the abbatial throne at the Phanar in Istanbul. This type of inlay work was, in a sense, foreign to Orthodoxy, but it arrived in Greece via simultaneous influence from both east and west. In the 15th-16th centuries, inlaid furniture was developed to great refinement in the Islamic world, and at the same time, Italian masters began a fashion of decorating choir stalls and sacristy cupboards with a tour-de-force of marquetry. So it is no surprise that Greek monasteries imitated the beauty of foreign inlay work, and thus baptized this craft into Orthodox tradition.

Much later, in the 19th century, inlay work became popular in American woodworking, not so much in fine furniture from urban centers, but in folk-woodwork, often made by farmers in wintertime. This American inlay-work often bears a striking resemblance to the old Athonite pieces. Whenever I observe a connection like this – an accidental resemblance of an American tradition to an Orthodox one, I know that it is a connection worth developing. After all, emphasizing these cultural sympathies is the natural way for Orthodoxy to become at home in a new land. As an artist, I also recognize that this process is periodically necessary to breathe new life into Orthodox tradition, to keep it fresh.

I hope you’ll agree that this carved and inlaid cross, made with materials and traditions from both sides of the world, constitutes a successful and inspiring marriage, and provides a glimpse of the staggering beauty that American Orthodoxy could potentially offer the world.

This is an absolutely sublime piece of work!

Many congratulations and thank you Andrew for disseminating to us all the wonderful fruits of your collaboration!

May Christ bless the work of your hands! All of them!