Similar Posts

The subject of this article — the “Znamenny Chantlet Database Project” — is a continuation of a proposal[1] initially unveiled by the author at the 2014 Pan-Orthodox Symposium on Orthodox Composition, held at Northern Kentucky University, and in a paper[2] given in 2015 at the Conference of the International Society of Orthodox Church Musicians in Joensuu, Finland, titled “Creating Liturgically: Hymnography and Music.”

Introduction

When modern-day Orthodox church musicians in North America gather, the subject often turns to the question of the future directions that liturgical singing in the New World might take: Can an American system of Eight Tones be developed, and what might it sound like? Can a stylistic bridge be built between the richly melodic received tradition of Byzantine chant and the syllabic chordal recitative that was received from the Eastern Slavic Churches of the Old World? Often absent from such discussions is the possible role that could be played by znamenny chant, a venerable body of canonical ecclesiastical chant[3] whose essence has yet to be thoroughly understood and whose potential has yet to be fully explored. The present article seeks to answer the following questions: Does znamenny chant have a place in Anglophone Orthodoxy in the twenty-first century? What are its artistic features that make it an exceptionally rich and expressive vehicle for musical worship – in any language? And what practical steps can be taken to bring it back into active use in the musical practice of the Orthodox Church?

Znamenny Chant: A History of Misunderstanding and Neglect

The very term “znamenny“ (correctly spelled with one “m” and two “n’s”) requires some elaboration, particularly for North American church musicians who may be relatively recent converts to Orthodoxy or even cradle-Orthodox who have not spend much time studying the historical development of liturgical chant among the Eastern Slavs. The designation “znamenny” appears as an attribution to some simple recitative-style chants, sometimes accompanied by the modifier “Little” or “Lesser”[4]: for example, “Only Begotten Son” and the Lord’s Prayer, as arranged by Dmitry Soloviev, the festal Antiphons at Divine Liturgy, and certain prokeimena. The chants supplied with these labels, however, are extremely abbreviated, simplified variants, which do little to demonstrate the deeper essence and expressive potential of znamenny chant in its richly melodic form (sometimes referred to as “great znamenny chant”[5]), which will be focus of this article.

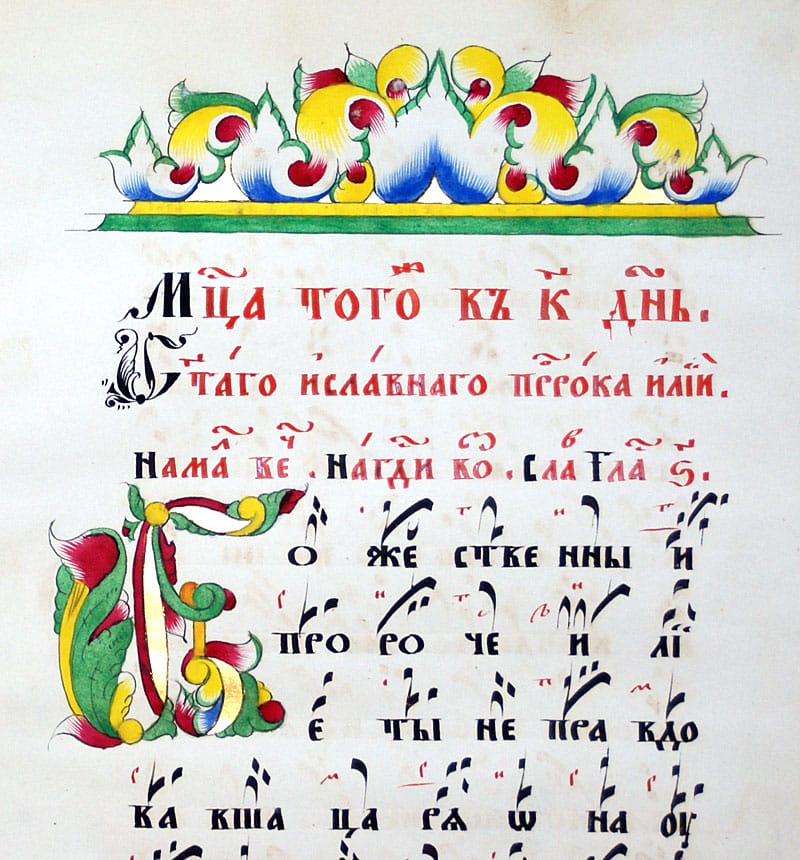

Even a cursory historical investigation into znamenny chant[6] is likely to elicit a certain amount of contradiction and confusion. On the one hand, one learns, it is the most ancient canonical chant sung in the churches of Kievan Rus’ and Muscovite Rus’ from the origins of Christianity in the year 988. But it scarcely sung today, except by “Old Believers” or “Old Ritualists,” a faction of Russian Orthodox believers that parted ways with the mainstream Orthodox Church in the 1660s. While znamenny chant was the earliest type of liturgical singing to be written down in early Rus’ (the very term “znamenny” is derived from the word “znamena” – the staffless signs or neumes that were used to notate liturgical hymns; thus “znamenny chant” might simply be translated as “notated chant”), yet, somewhat ironically, the earliest forms of its notation remain unreadable even to modern-day scholar-specialists, to say nothing of the average church singer. Despite its venerable pedigree in Russian musical culture, the average Russian Orthodox churchgoer today is largely ignorant of its very existence: if they were to hear it sung in church, they would likely not recognize it as something familiar or “traditional,” and might even be inclined to reject it as something foreign and overly bookish.

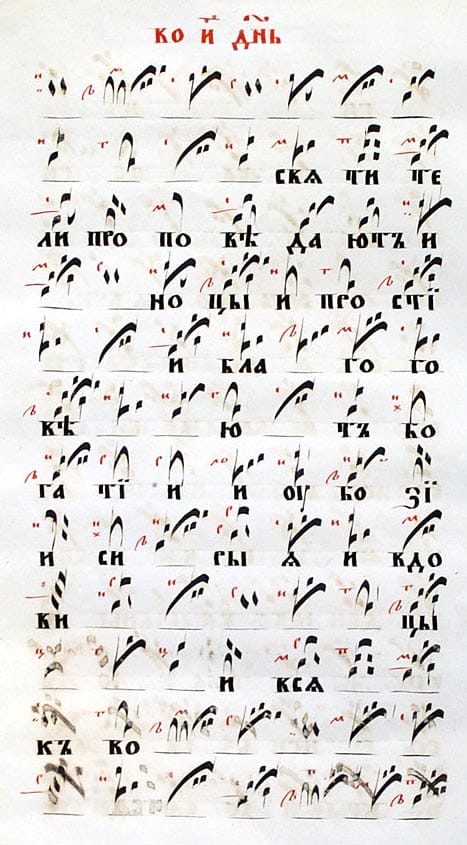

Thus, it has been the peculiar fate of znamenny chant to be rather thoroughly neglected, not to say ostracized, by the very Church — the Russian Orthodox Church — in which it was, and formally remains to this day, the official, canonical chant, published and re-published for at least a period of 250 years in a comprehensive set of unison chant books[7] notated in five-line “square-note” staff notation,[8] but scarcely ever sung at church services. The reasons for this odd state of affairs are rather complex, and have to do more with large-scale developments and trends in Russian culture than with the actual artistic or creative merits of znamenny chant melodies themselves.

Znamenny chant continued to be actively sung well into the mid-seventeenth century, and was, in fact, experiencing a period of flourishing and some positive notational reforms,[9] when it collided headlong with a new style of rendering liturgical hymns — harmonic singing in parts, patterned upon Western European models, which had entered the Russian Church from Roman Catholic Poland via Ukraine. Readily embraced by the Tsar and the Patriarch, who were the leading trend-setters of Muscovite society, the new style of singing brought with it five-line staff notation, which rapidly displaced the staffless neumatic notation, but not without the loss of certain nuances of vocal execution and articulation that the neumes conveyed. More crucially, the very nature and character of the compositional process was transformed as it pertained to church music.[10] In the words of the eminent Russian musicologist and historian, Antonin Preobrazhensky (1870-1929),

…creativity was simplified: the composer was not required, as before, to penetrate deeply into the substance of znamenny chant, or to maintain a link with the internal content [of the text]. The new style freed the hands of any musically gifted singer to create melodies that had no connection with the melodic treasures accumulated over the centuries, but rather were naive in their simplicity and incredibly impoverished, both in rhythm and overall structure by comparison with the objective yet profound znamenny melodies.[11]

As a direct consequence of these developments, which went hand-in-hand with the general secularization and Europeanization of Russian culture and musical life, compositional creativity in the realm of sacred music was channeled into writing colossal Baroque-style sacred concertos for 4, 8, 12, and more voices and, later in the eighteenth century, into motet-like choral settings of the unchanging hymns of the All-Night Vigil and Divine Liturgy, which used the full expressive arsenal of Western European music of late Baroque, Viennese Classical, and early Romantic periods. Concurrently, the changing hymns of the Octoechos and the various feasts assumed a distinctly secondary position of importance.

Within the codices of znamenny chant one could find two basic types of melodies: 1) the so-called “great” chant—richly inflected melodies of the syllabic-neumatic type (typically having two to six, and occasionally more, notes per syllable), which were normative for the hymns of the Resurrectional Octoechos, the propers of Feasts as well services of the Lenten and Flowery Triodia; and 2) the “lesser” chant—largely syllabic melodies (often given as only a single example or pattern) that were intended for daily (ferial) services. These latter variants, the “lesser” or “little” znamenny chant, gradually took on a life of their own, assuming a position of predominance, particularly at the Chapel of the Imperial Court, where they came to be known as “Kievan” (since most of the Chapel’s singers were recruited in Ukraine) or simply “obikhod” (meaning “common” or “customary”). The chief “virtue” of these melodies was their brevity and efficiency, which made them appealing to upper-class churchgoers in St. Petersburg, the new “Western” capital of Russia, who were not inclined to favor lengthy, elaborately sung church services. The abbreviated melodies also lent themselves to being harmonized in basic triadic harmony, which initially was improvisational but eventually became codified in the mid-nineteenth century.

The square-note chant codices containing both “great” and “little” znamenny melodies in unison were initially published in 1772 and continued to be reprinted (with minor editorial revisions) until 1909. In practical use, however, they were almost completely supplanted and superseded by the publication, in 1848, and again in 1869, of the Imperial Chapel Obikhod,[12] largely in 4-part harmonic recitative, copies of which were disseminated to every church in Russian Empire, and the use of which was mandated by law whenever any member of the extended Royal Family was in attendance. The neglected state of the unison square-note codices can be gleaned from the experience of Tchaikovsky, who, when he was gathering chant materials on which to base his All-Night Vigil, opus 52 (1882), was advised by the chant scholar Archpriest Dmitry Razumovsky (1818-1889) to visit churches in the countryside and to listen to the chanting of village cantors. By all indications, Tchaikovsky followed this advice, but found that even in the villages, the unison znamenny chants had largely fallen out of use.

Nonetheless, Tchaikovsky became the first Russian composer of major stature to devote any attention to the forgotten legacy of early unison chants example, and following his example, a sizeable group of nationally minded Russian composers,[13] most of them affiliated with the Moscow Synodal School of Church Singing and its Choir, made a concerted effort to rediscover the melodic “great” znamenny tradition and to use znamenny melodies as the basis for their polyphonic arrangements. In some respects, this “New Direction” in Russian Orthodox sacred musical composition can be likened to the rediscovery in the late nineteenth century of the iconographic works of such ancient masters as Andrei Rublev (c. 1360-1427 or 1430) and the anonymous iconographers affiliated with Novgorod, Suzdal’, Vladimir, and other ancient Russian cities. The result was the emergence of a new style of iconography, reflected in the works of Victor Vasnetsov (1848-1926), Mikhail Vrubel’ (1856-1910), Mikhail Nesterov (1862-1942), and others, at the turn of the twentieth century. Their approach to iconography, coupled with the scholarly works of such authors as Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky, has substantially altered present-day Orthodox iconography in both the realm of the Eastern Slavs and North America.[14]

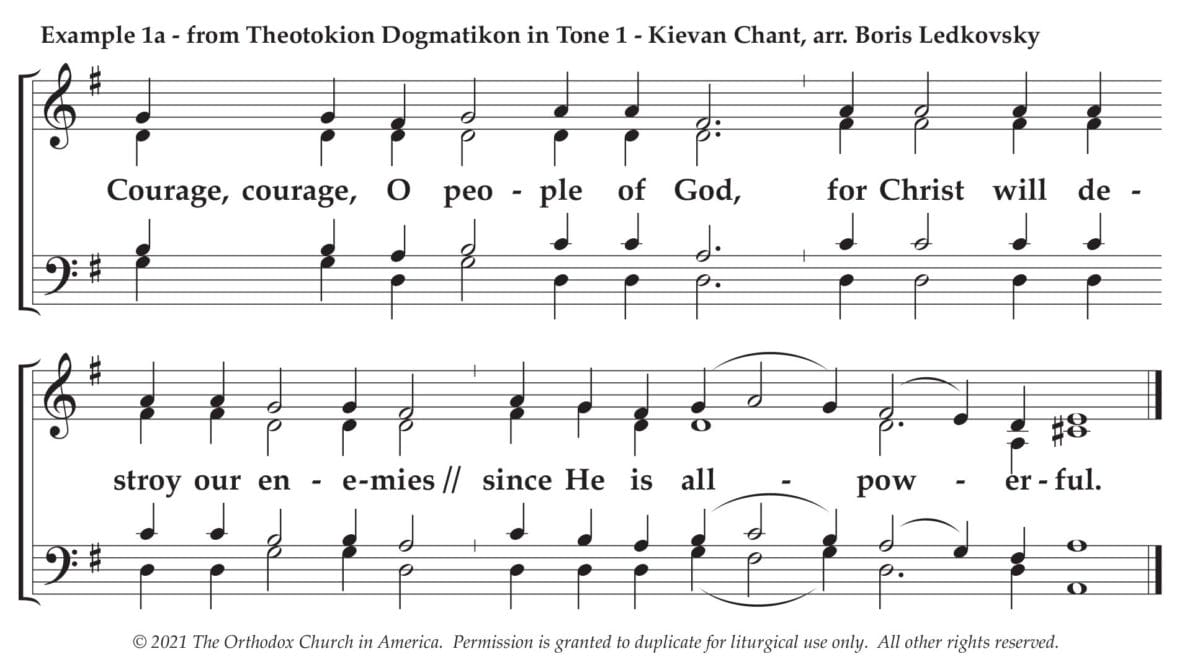

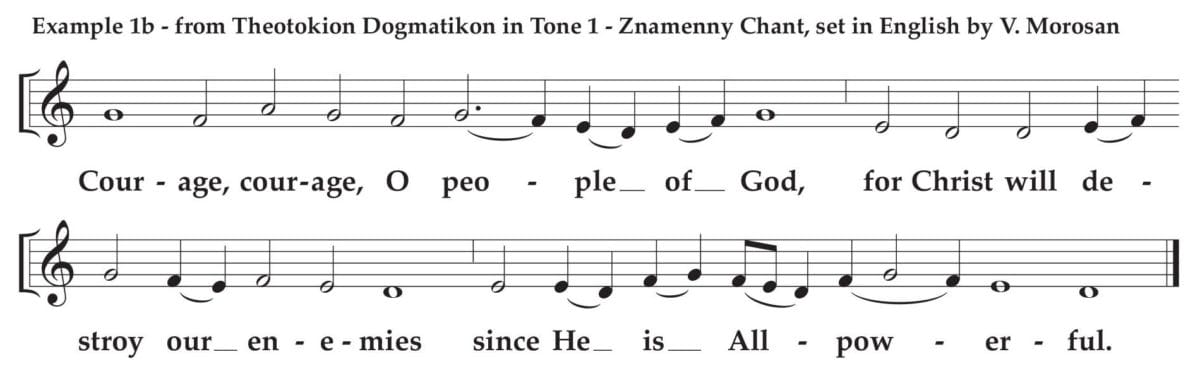

In the area of liturgical singing, however, the bulk of the melodic znamenny tradition remains unexplored to this day. As in the case of the Russian composers of the “New Direction,” present-day English-language adaptations have been largely limited to the Theotokia Dogmatica in the Eight Tones of znamenny chant.[15] Only in a few parishes and monasteries have znamenny melodies been adapted into English more widely.[16]

The Aesthetic Advantages of a Znamenny Chant Revival: Parallels with Iconography

If one were to explore some of the principles that lie at the basis of the twentieth-century return to traditional models and techniques of iconography, one would certainly focus on the ways that the traditional icon seeks to portray and express the “spiritual nature,” as opposed to a realistic, naturalistic portrayal of its subjects. A discussion of the ways in which modern-day iconographers achieve this lies far beyond the scope of this article. Without delving into the technical aspects of the painter’s technique, one can also recognize the beauty of the colors, the harmony of the composition (typically based upon age-old patterns), the subtlety of lines and shading, and, last but not not least, the “reverse perspective,” which locates the point of view within the person or scene depicted, rather than with the outside viewer, as is the case in much Western painting since the time of the Renaissance.

While it is difficult to extend exact parallels into the realm of liturgical music, we can draw certain analogies. Chief among them is the fact that, at the center of attention in any piece of liturgical music lies the text: it is the presence of text which distinguishes liturgical singing or chant from “music.” To this central role of text in liturgical singing we may contrast the principle of “atextalis” (literally, “atextuality”), expressed in a late seventeenth-century theoretical treatise by Nikolai Diletsky (c.1630-c.1690), The Idea of Musical Grammar, which asserted that music has an independent existence from the text: “If a [musical] fantasy comes to you, write it down for [later] use in concertos. If it doesn’t fit one text, it may fit another.”[17] Moreover, from the standpoint of musical expression, the ideal purpose of a liturgical melody is to impart a “heightened utterance” to the text, serving as an optimal vehicle for its being sounded in the course of communal, liturgical worship: mirroring and intensifying the aural contour of the individual words and syllables, emphasizing important words and phrases, and occasionally highlighting key words, names, and concepts by means of strikingly distinct melismas, [18] ranging in length from a dozen to several dozen notes. On a larger scale, a well-constructed chant will use devices of musical form to heighten and accentuate parallel phrase structures or allusions in the poetry of the liturgical text.

On the “negative” end of the expressive spectrum, liturgical chant does not attempt to play upon the emotions of the worshipper, nor can it easily do so, lacking the harmonic means of creating tension and resolution; it does not overtly engage in naturalistic text painting by means of musical sounds, since its melodic vocabulary is limited by the melodic kernels (which we have termed “chantlets”[19]—the building blocks of chant); nor can it startle and surprise the listener by dramatic sound effects, since a wide range of dynamics, from pianissimo to fortissimo, is also not in the expressive arsenal of the chant composer.

A melodically developed chant melody, constructed in a manner similar to “great”[20] znamenny chant, is ideally suited at delivering the actual sound and, through it, the cognitive meaning of any given liturgical text, which makes it an excellent tool for the all-important functions of prayer, doxology, education, edification, and evangelization in the course of liturgical worship. To draw another parallel to the visual, iconographic realm, if dramatic, sentimental, or treacly polyphonic compositions correspond to realistic, naturalistic “icons,” with rosy-cheeked Madonnas and pudgy, naked cherubs, well-constructed melodic chant comes from the same liturgical aesthetic and ethos as “traditional” Orthodox iconography. Seen from this perspective, the rapid-fire, harmonically primitive liturgical recitative of the Imperial Court (Obikhod) Chant, so familiar to modern-day churchgoers, would be akin to a scenario in which all icons would be reduced to black-and-white line drawings!

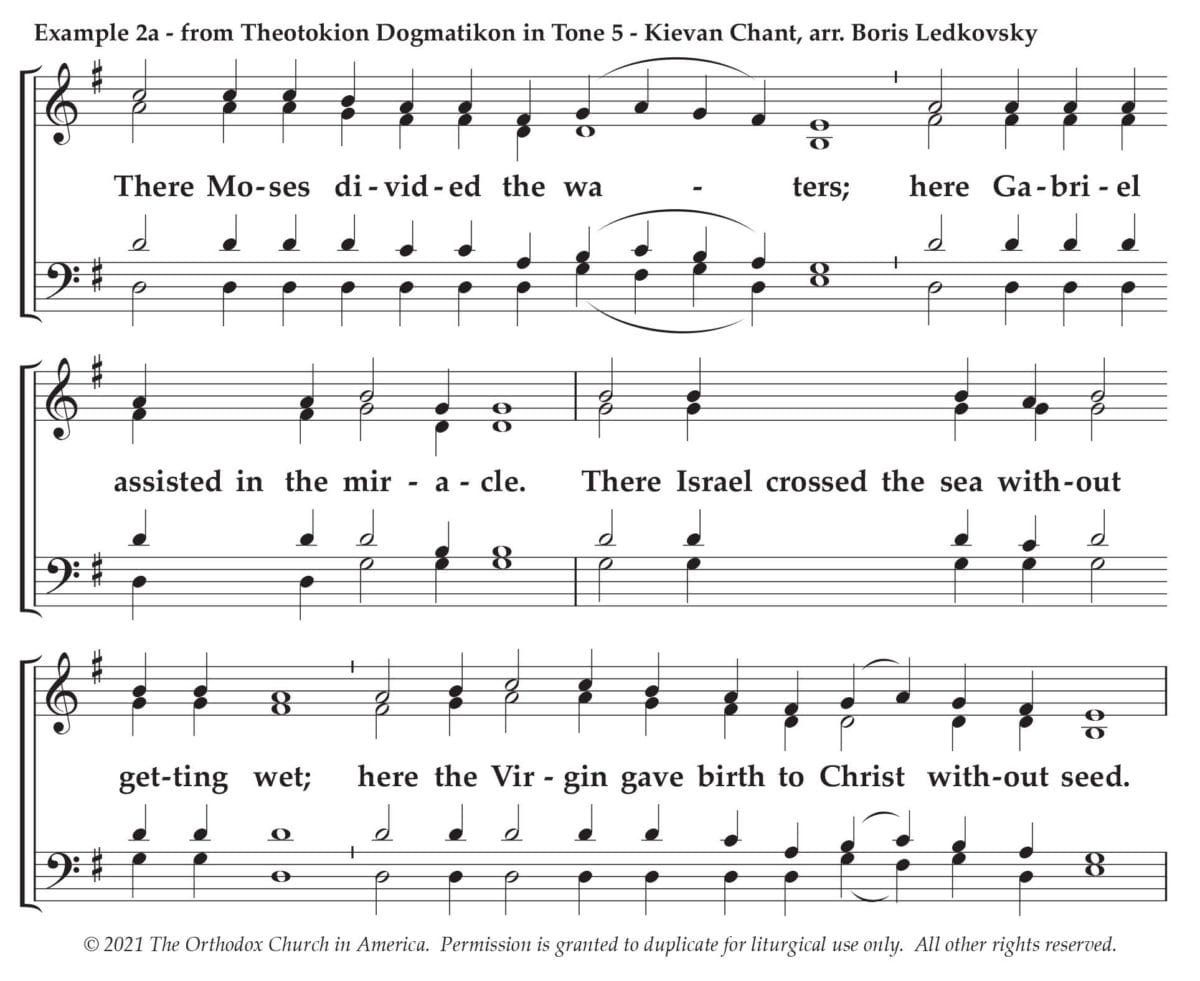

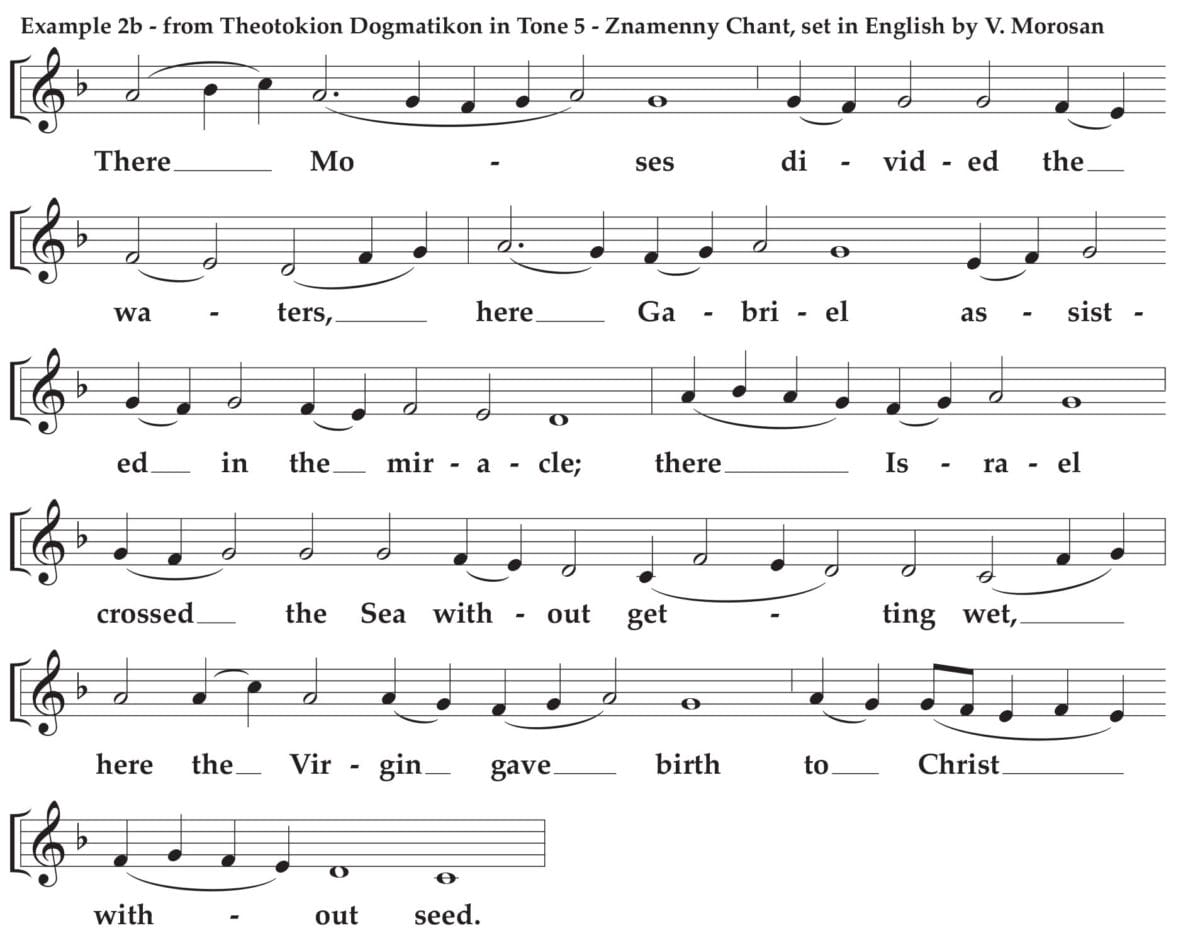

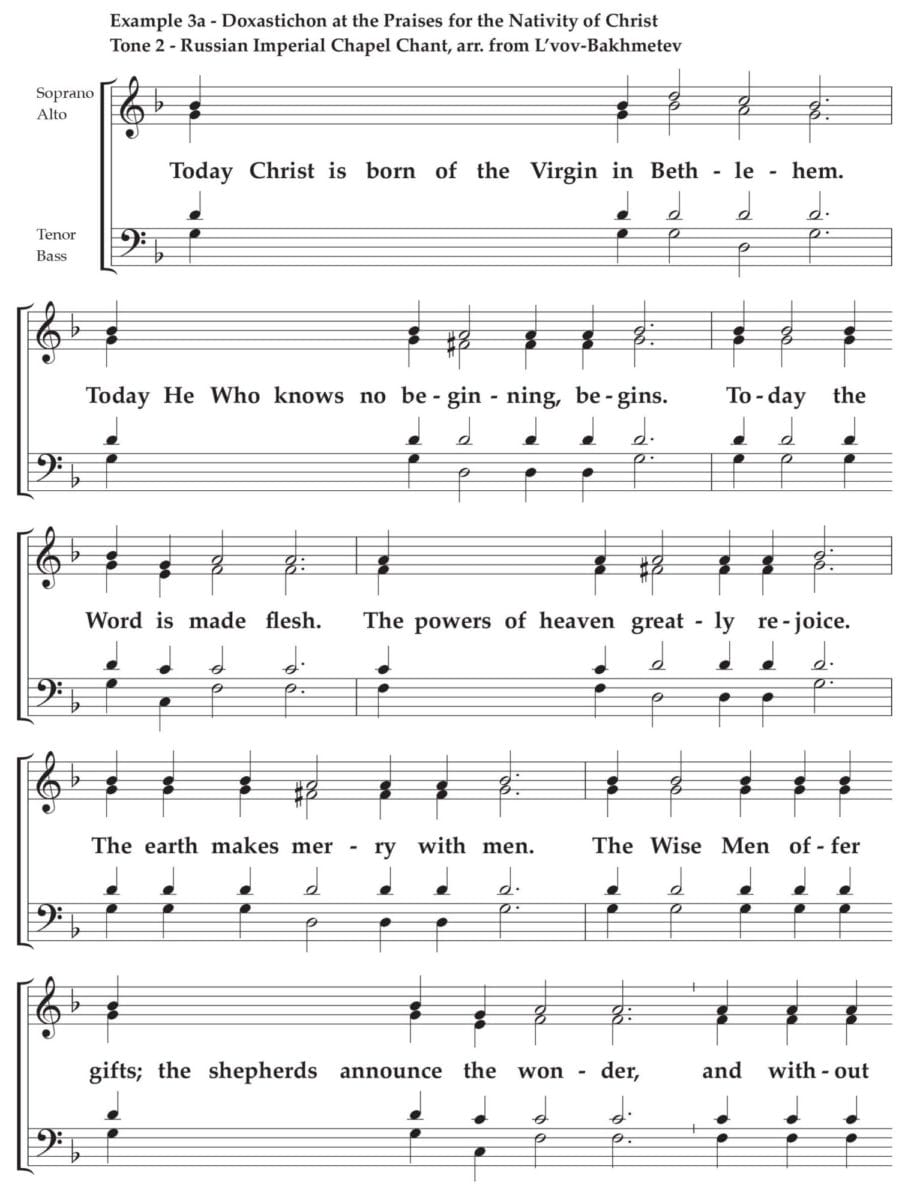

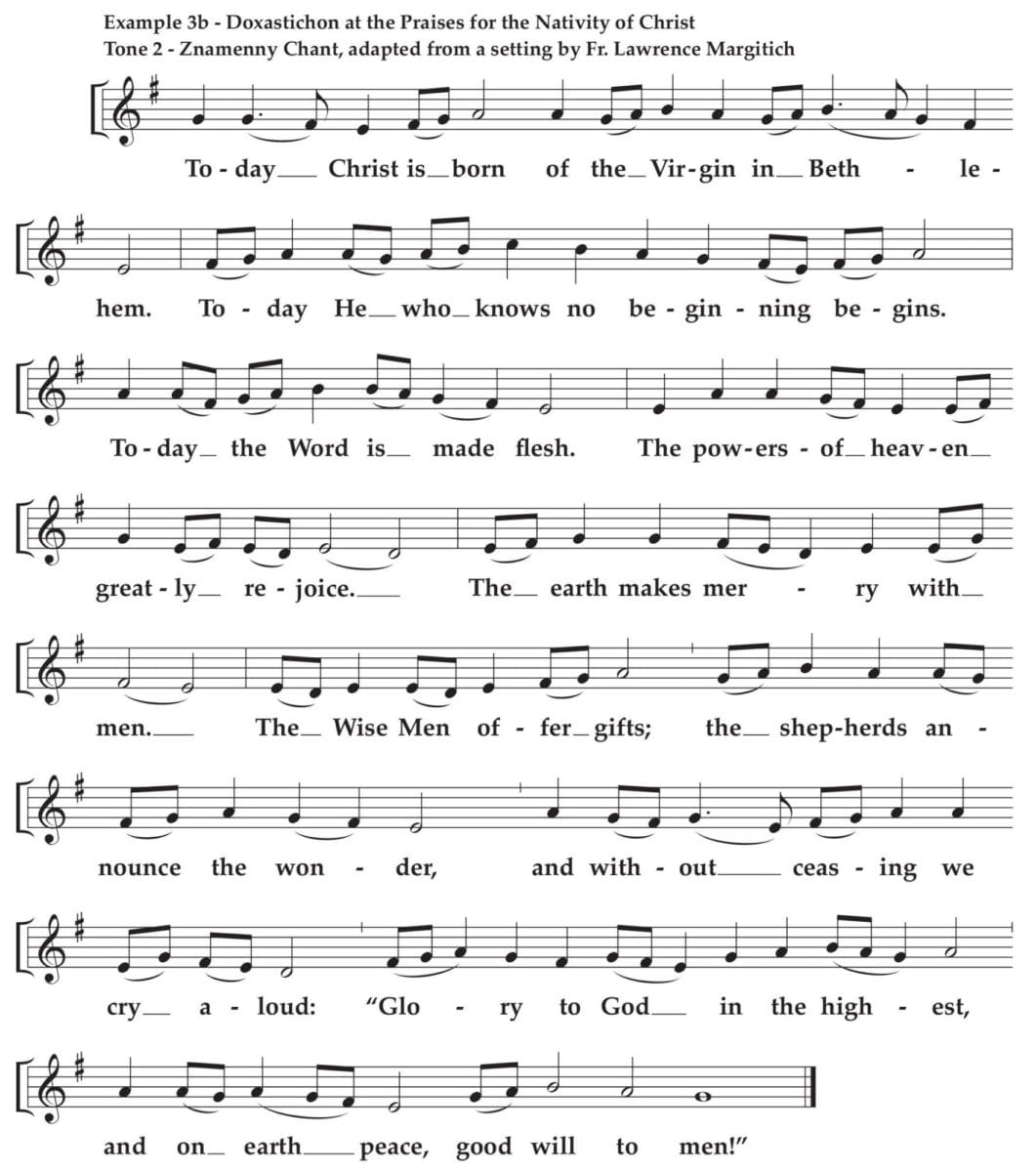

A few well-chosen examples will illustrate this point.

The clear advantages that znamenny chant offers for enriching liturgical singing in twenty-first century North America and elsewhere in the ever-expanding Orthodox world should be evident from the above examples. Admittedly some substantial hurdles must be overcome before such an enrichment can take place, however. One significant problem lies in the fact that while polyphonic composition, whether harmonic or contrapuntal, is widely studied and taught in musical institutions around the world, only a scarce number of individuals in the West have studied and analyzed znamenny chant, applying those insights on the level of practical composition. The vast majority of scholarly investigations into znamenny chant are in Russian, and most of them have a narrow, academic focus, largely, if not entirely, divorced from liturgical practice. This has led to a widespread but mistaken perception that engagement with znamenny chant is solely an historical, academic pursuit, lacking any practical significance.

Quite the contrary is true: the centonic[21] nature of znamenny composition, which provides the composer with a vast array of melodic kernels—chantlets—that can be combined in an infinite number of ways, molded to deliver any given text with maximum aural, linguistic, and cognitive impact, making znamenny chant an appropriate vehicle for new composition in any number of different languages besides the original Church Slavonic. The current “Znamenny Chantlet Database Project” aims to systematize and bring to light the compositional vocabulary of znamenny chant for the greater musical world, where it can garner the attention of future chant composers who desire to work within its parameters. In this regard, the Project can be likened to the groundbreaking work done by St. Anthony’s Monastery in Florence, Arizona, which has contributed to the resurgence of Byzantine chant in the last several decades.

+ + +

The Znamenny Chantlet Database Project: A Practical Description

In the paper given at the Joensuu Conference of the ISOCM in 2015, I presented the idea of a collaborative effort in which various volunteers, working from any location in the world, would proceed to build a centralized database, visually capturing (by means of screenshots) and indexing the vast array of znamenny chantlets, drawing them, phrase by phrase, from the various Church Slavonic square-note chant books. The square-note chant books were selected because of their ready availability in PDF scans, and the relative ease with which any trained musician can learn to read them. They are all:

- printed in alto clef on a five-line staff

- employ readily identifiable mensural note values

- clearly delineated into readily identifiable phrases of text having a particular number of syllables, and

- display an unambiguous pattern of textual accentuation within each phrase, since every polysyllabic Church Slavonic word carries an accent mark that identifies the stress.

After capturing the graphic image of the phrase, the volunteer analysts would:

- identify and code the source from which the particular phrase was drawn

- enter that graphic image into a container field within a database

- express the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables by means of zeros (0) and ones (1)

- note the starting and ending pitches

- note the position of the given phrase within a larger context of the musical phrase: initial, middle, cadential

- note the prevalent position (if any) of the phrase within the beginning, middle or ending of the particular hymn

Additional steps (not currently within the scope of the project) might involve:

- expressing the given chantlet by means of znamenny staffless, neume notation (using available fonts developed by Aleksandr Andreev and Nikita Simmons)[22]

- transcribing each chantlet into common Western round-note notation (which may eventually be possible using some type of OCR and AI)

In its initial form, the project proposed the use of a database program called FileMaker Pro (Claris Software); however, such a plan entailed the use of a hosted database and the acquisition of the FileMaker software by each of the volunteers, which was a cost-prohibitive proposition for many potential collaborators.

These obstacles no are no longer a factor due to the rise of Airtable, a browser-based, platform-independent, web-hosted database program, which, moreover, is free (within certain limitations that do not impinge upon this project). The viability of Airtable, as well as the database design, have already been tested and implemented. Several volunteers have come forward, offering their services, and are in the process of receiving some orientation and basic training. All the project needs now is additional volunteers, who would be willing to spend a few hours each week doing the basic graphic capture and indexing work as described above.

The following video contains a detailed demonstration of the process entailed in capturing and cataloguing the chantlets:

Upon successful completion, the database will offer the prospective composer of new chants in the znamenny style an array of possibilities, all of them grounded in actual examples, and identifiable in relation to the original source chants for a more complete context. Faced with an English phrase having a certain array of syllables and accentuation pattern, the composer will be able to search for comparable examples across the sizeable corpus of znamenny chant. Obviously, there may be a number of different choices, at which point the composer’s awareness of the overall context and form will allow him or her to make creative choices and decisions, much in the way that an iconographer follows an existing model while imbuing it with their own creative content.

Is Znamenny Chant Needed in 21st-century America?

One may reasonably ask whether a revival of znamenny chant composition is what Orthodox America needs in the twenty-first century. While there are certainly many challenges of both a spiritual and practical nature that would need to be overcome, there seems to be a distinct desire on the part of many inquirers, seekers, and converts, to discover the full depth and breadth of Orthodox tradition, including its liturgical arts, and not a diluted, dumbed-down version adjusted to appeal to modern life. In this connection an interview with Andrey Kotov, the founder and leader of the Sirin Ensemble for early spiritual music, offers some insights into what znamenny chant can offer to those who seek a deeper and more profound experience of Orthodox liturgical worship:

I was mesmerized by the power of the chant and the feeling invoked by unison singing. Few people can do it today. When you sing in unison, you don’t hear yourself singing as your voice merges with the entire choir. It is called “singing with one mouth.” Neither your voice, nor the voice of the cantor can be distinguished. You don’t hear yourself sing, you hear the prayer and become a part of it. For a modern man, it is difficult to understand, because to a certain extent we are all raised as individualists, we all have our egos and our own beautiful voices… While for traditionalists, singing together means experiencing feelings together….

We keep saying the word “tradition”, but what does it mean? It is a collection of positive experiences that is handed down from generation to generation because it is good. Like traditional recipes from our grandmother, we receive it from our ancestors, because despite the temporality of everything in this world, some valuable things can be passed on to future generations. And it is done in a way that is relatable and valuable for children….[23]

Just as the “Znamenny Chantlet Database Project” is only the very first step in reviving a school of znamenny chant composition in the English language, so the introduction of znamenny chant (in both its unison and possibly polyphonic forms) would be only the first stage in using liturgical music to draw churchgoers into a deeper experience of the Church’s hymnography with all of its didactic and spiritual qualities. As the wise, late twentieth-century Russian elder, Archimandrite John (Krestiankin) (1910–2006), is reputed to have said: “In order to sing znamenny [chant], we must live a ‘znamenny’ life!” His words point to the exalted role and position that znamenny chant played in former centuries as a sacred “sonorous language” that was used exclusively for prayerful communication with God, rather than simply being another “flavor” of musical expression amidst a vast array of other possibilities.

Andrey Kotov further expands upon this thought: The organic melodic expression of any national culture is created by its language. The melodic content of a language is naturally contained in the words people pronounce. Singing is differentiated from speech only by the fact that in singing that melodic content is rhythmicized. “Traditional singing is a part of traditional life,” Kotov continues. “If there’s no traditional society, there won’t be any traditional singing. It will either become an archaic art or simply disappear.” But, in any case, he adds, “Znamenny chant must be sung in such a way that people would want to listen to it.”[24]

Orthodoxy in North America has scarcely begun to take baby steps in the direction of creating its own sacred indigenous language of musical prayer, based upon English.[25] Whatever name such a chant may eventually become known by, the “Znamenny Chantlet Database Project,” we believe, will contribute significantly to its development.

Anyone interested in joining the team that is working on the Znamenny Chantlet Documentation Project, please contact Vladimir Morosan (vlad@musicarussica.com) or Constantine Stade (constantine@thechurchbellcompany.com)

If you enjoyed this article, please use the donate button at the bottom of the page to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

[1]“A Methodology for Composing Chant in English Using Znamenny Models,” by Dr. Vladimir Morosan. https://youtu.be/pE7ZPGau5wQ

[2] Vladimir Morosan, “A Collaborative Open-Source Database of Znamenny Chant Formulae,” paper given at the 2015 ISOCM conference titled Creating Liturgically: Hymnography and Music. Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Orthodox Church Music, University of Joensuu, Finland – 8-14 June 2015

[3] On canonical chant – see Gardner, Johann von. Russian Church Singing, Vol. 1: Orthodox Worship and

Hymnography. Translated by Vladimir Morosan. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1980, pp. 101 ff.

[4] Designated as malyi znamenny in Russian.

[5] Designated as bolshoi znamenny in Russian. Such designations are by no means universal in the chant sources: more often than not the descriptive adjectives are omitted, and one has to conclude whether a chant is “little” or “great” on the basis of the melodic structure of a given melody.

[6] See, for example, Milos Velimirovic, “Russian and Slavonic Church Music”. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Stanley Sadie, ed. (1980). London: Macmillan. ISBN 1-56159-174-2.

[7] The chant books include: the Obikhod notnago peniia [The common hymns in staff notation], the Oktoikh notnogo peniia [The Octoechos in staff notation], the Irmologii notnogo peniia [The heirmologion in staff notation], the Prazdniki notnago peniia (The feasts in staff notation), Triod’ postnaia (The Lenten Triodion) and Triod’ tvetnaia (The Flowery Triodion).

[8] Regarding square-note notation, see Morosan, Choral Performance in Pre-Revolutionary Russia, 2nd edition. Guilford, Connecticut: Musica Russica, 1986, pp. 251ff.

[9] See Vincent Peterson, “The Azbuka of Alexander Mezenets: A Preliminary Study in Znamenny Chant.” M. Div. thesis, Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, 1981.

[10] See Vladimir Morosan,“Penie and Musikiia: Aesthetic Changes in Russian Liturgical Singing During the Seventeenth Century,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly, vol. 23, No. 3/4, 1979.

[11] Antonin Preobrazhensky, “Ot uniatskogo kanta do pravoslavnoi kheruvimskoi” [From a Uniate kant to an Orthodox Cherubic Hymn], Muzykal’nyi sovremennik (February 1916): 11-29, quoted in Morosan (1986), p. 43.

[12] Obikhod notnago tserkovnago peniia pri Vysochaishem Dvore upotrebliaemyi [The Common Book of notated church singing as used at the Highest Court]. St. Petersburg: 1848; revised edition, 1869.

[13] Led by Alexander Kastalsky (1856-1926), who was the acknowledged leader and trend-setter, this group included such names as Aleksandr Gretchaninoff (1864–1956), Viktor Kalinnikov (1870-1927), Aleksandr Nikolsky (1874-1943), Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943), and Pavel Chesnokov (1877-1944).

[14] Reflected in the works of Fr. Gregory Krug, Archpriest Andrew Tregubov, Heather MacKean, Dmitry Shkolnik, to name just a few.

[15] As adapted by Vladimir Morosan. Published in Great Vespers: A Common Book of Church Hymns, ed. by Benedict Sheehan, Hierodeacon David, and Paul Kappanadze. South Canaan, Pennsylvania: St. Tikhon’s Monastery Press, 2020.

[16] The adaptations of Fr. Lawrence Margitich of St. Seraphim Cathedral (OCA), in Santa Rosa, California, and Holy Cross Monastery in Wayne, West Virginia, are the most prominent examples.

[17] Stepan Smolensky, “Musikiiskaia grammatika” Nikolaia Diletskogo [Nikolai Dilensky’s “Musical Grammar”], transcription and commentary, (St. Petersburg: n.p. 1910), p. 178. A facsimile edition of a manuscript copy dating from 1723 has also been published: Mykola Dylesky, Grammatika muzykal’na (Kyiv: Muzychna Ukraina, 1971).

[18] Known as fity (sing. fita), so called because they were encoded by the Greek/Slavonic letter theta, accompanied by some other distinguishing markings that differentiated one such melisma from another.

[19] The term “chantlet” bears the same etymological relationship to the word “chant” as does its Russian equivalent, “popevka,” to the words penie (singing) and raspev (chant melody).

[20] Bolshoi, as opposed to malyi (see notes 4 and 5 above).

[21] The centonic approach to musical composition entails assembling stock melodic fragments (“chantlets”) to create complete chant melodies, thus creating sets of musically related melodies that are at once unique and at the same time related one to another, classified according to a given glas (Tone) or echos.

[22] Aleksandr Andreev and Nikita Simmons, fonts-znam — fonts for Znamenny Notation, version 1.1, March 8, 2021.

https://www.ponomar.net/files/fonts-znam.pdf (accessed 01-13-23).

[23] Vladimir Basenkov, “Znamenny chant must be sung in such a way that people would want to listen to it.”

Interview with Andrey Kotov, the leader of Sirin Ensemble, translation by Talyb Samedov, Pravoslavie.ru

1/3/2022, https://orthochristian.com/109820.html (accessed 01-13-23).

[24] Ibid.

[25] See Vladimir Morosan, “What It Means to be an American Orthodox Composer: The Case of Fr. Sergei Glagolev (1928-2021)” Jacob’s Well (Issue 6, Spring/Summer, 2022) https://www.jacobsmag.org/morosanglagolev (accessed 01-13-23)

Thank you, Vlad, for this fascinating article. I’m curious how you feel about the question of harmony. We Americans live in a culture of harmonized choral singing. While I love Znamenny melodies, hearing them sung by a mixed choir in unison feels unnatural to me – artificially austere, even cultish – and very hard to keep perfectly together. It just doesn’t seem like a natural way for modern Americans to sing in church. How do you feel about harmonized Znamenny chant – like the Cherubikon arranged by Margitich and Sheehan?

It’s not just a question of it not feeling natural to modern Americans, although that’s a good point. One of the reasons part singing developed was to accommodate a wide range of voices. I personally have a really hard time singing anything in the alto range, while my son is a true basso profundo. I know women who thought themselves unable to sing until they tried singing in the tenor range. If you really want congregational singing, which is certainly desirable, it would be ideal to develop a simple three-part harmony, with the melody in the alto, the sopranos singing a third above, and a solid supportive bass line. Harmonic singing is the hill I die on.

On the question of vocal range, I have heard mixed choirs of Russian Old Ritualists sing in a 3-octave unison, which, if done well, is quite a sound in and of itself! But as I said in the previous comment, the main reason for exploring the possibilities offered by znamenny chant lies in the “horizontal” plane — the relationships of melody to text and text to melody. Complexity of melody is not as much a factor as some might think: at a conference some years ago I heard a Carpatho-Russian congregation of several hundred people boldly sing the Theotokion Dogmatikon (by memory!) divided into 2 choirs (men and women) in 3-part harmony. Those people, gathered from many different parishes, *knew* their sacred liturgical singing! As the CSN&Y song goes, “Teach your children well!” and all sorts of things become possible. But it’s easier to teach a *memorable* melody, connected inextricably with a sacred text, than a 2- or 3-note formulaic recitative.

There’s a lot to be said for the ‘ethos’ of each particular community: when people enter their church they *expect* to hear a certain kind of sound. If they hear something radically different, it will make them uncomfortable, or, as you say, “unnatural.”

And yes, unison singing is very difficult to do well, and will immediately bring out the shortcomings of a choir… but it can also help them become much better in the process.

This being said, znamenny chant has been sung in many different ways over the centuries, including 2-, 3-, and 4-part (even 8-part) harmony and counterpoint. The main area where I see the advantage of the znamenny approach is in the melodic treatment of the text and the expressive possibilities it opens up for text declamation rather than the rat-a-tat-tat of common harmonized Slavic chant. How such melodies are rendered polyphonically is for future generations of Orthodox composers to decide.

This is a very interesting project. It is helpful that the old neumes are being transcribed to modern notation for use by contemporary American musicians. While St. Anthony’s has transcribed a lot of finished Byzantine music, it has left the “chantlets” in Byzantine notation. I get the reasoning. Western notation is limited in its capacity to represent Greek tonality and ornamentation. However, few in America, despite the claims in “My Big Fat Greek Wedding” are Greek, and have an ear to strictly duplicate the nuances of Byzantine chant, or Russian, for that matter, as more closely related to Western music it may seem.

The advantage of Byzantine chant in the West, however, is the emphasis on tonality, as foreign as it may sound, while Russian chant, I gather, is more arranged around melodic phrases or harmonic progressions. I am Antiochian and, to my convert’s ear, I can tell Byzantine tone 2 from 3 much easier than trying to memorize all the different phrases of Russian tones 2 or 3, even if, harmonically, it seems more familiar. As much as I enjoy part singing, I think most American congregational singing consists of melody and a vague drone; the American “ison.” Harmony and part singing are not universally intuitive.

Of course, we have both Greek and Russian, and more, in America. What is the history of Znamenny? How was what was brought from Constantinople adopted and made native? I guess we can look at Alaska to see how what was brought there was made native.

But, the West does have it’s own eight tone system already, which bears the name of an Orthodox patriarch. It is also based on tonality, as Byzantine. Is there a place for that in the American Orthodox Church?

You make a number of interesting observations, Chris, but a few require special mention. As I state in the article, znamenny singing is worlds removed from the 4-part chordal recitative heard in most Slavic-origin parishes in this country. Some would argue that singing in 4-part harmony using familiar major and minor chords is *closer* in its “musical ethos” to the ears of American converts than the unusual-sounding modes of Byzantine Chant, or, for that matter, the florid unison melodies of znamenny chant. This is a chapter in the development of American Orthodox liturgical singing that still remains to be written.

You ask “What is the history of Znamenny Chant? Well, a summary can be found here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Znamenny_chant For a real deep dive, I would recommend Johann von Gardner’s “Russian Church Singing,” volume 2, which covers the period of historical development from the origins to 1650: https://svspress.com/russian-church-singing-vol-ii/

Finally, you mention “the West having its own eight tone system, bearing the name of an Orthodox patriarch.” (great Orthodox Jeopardy question!) You’re referring of course to Pope Gregory the Great (590–604), recognized as a saint, who is credited with collecting and codifying Gregorian Chant. St Gregory’s status and credentials notwithstanding, most Orthodox folks, I suspect, would be very surprised if they came to church one Sunday morning and heard Gregorian Chant being sung. (See my earlier comment about people’s expectations when they come to church to worship). For those interested in tasting a sample, however, you can go here: https://www.archdiocese.ca/articles/monks-release-second-volume-highly-acclaimed-orthodox-hymns-gregorian-chant

hELLO vLADIMIR: Just to write how enjoyable it was to read this. As a non-musician, it clarified many points of interest. I remember Fr. Sergei Glagolev, one of my mentors, did try his hand at translating Znamenny music into English language. I dont know if he succeeded, but I enjoyed hislectures about this. Phil Tamoush

Hello, Phil,

How wonderful to hear from you! Father Sergei Glagolev, of blessed memory, was an inspiration to many of us!

So much this!

But I am tantalized by this quote, and wonder about the particulars:

“ Once I was in one monastery at the Liturgy, and there I heard for the first time so-called “stolbovoy’chant. The Cherubic Hymn and “A Mercy of Peace…” made a powerful impression on me. There were few people there, and I stood alone in a corner and cried like a child. After the Liturgy I dropped in to see the abbot and questioned him about my impressions.

“And you, in all likelihood, have never heard stolbovoy chant?” the abbot asked me.

“No,” I replied, “I’ve never even heard the name.”

“And what is a stolbovoy nobleman?”

“Well, this means someone who is of an ancient lineage.”

“That’s how it is with stolbovoy chant—it’s an ancient chant. We adopted it from our fathers, and they from the Greeks.”

Now stolbovoy chant can rarely be heard anywhere; it’s being forgotten. Many new melodies are appearing—those of Alyabyev, Lvov, and others. True, even from among the new ones there are unusually talented ones, such as Turchaninov. His melodies are known not only in Russia, but abroad as well, even in America. The English also appreciate him.”

—From the bio of (St.) elder Barsanuphius of Optina

Thank you for this quote, John. It is intriguing that the term used in this exchange with the Elder is “stolbovoy” — related to the modern Russian word “stolb” — meaning post or pillar. Johann von Gardner in his seminal work “Russian Church Singing” uses the word “stolp” and its derivative “stolpovoy” — an older form of the word “stolb.” In a sense, it is as generic a term as “znamenny” (derived from “znamia” — “sign” or “mark”), which Gardner equates with “stolp” chant. Just as posts along a road serve to mark the way and orient the traveler, so the “signs” of znamenny chant guide and orient the singer how to direct his voice. The signs were necessary to remind singers of less familiar, rarely sung hymns, such as feast-day hymns, whereas commonly sung, everyday hymns were likely passed along by oral tradition, which is why many of the most common hymns of Divine Liturgy and Vigil are not found in surviving chant books.

Thank you for this delightful article about an exciting project!

It seems that the Anglophone Orthodox sphere of Slavic musical tradition may be at a point now, musically, comparable to where the Anglophone Orthodox sphere with Byzantine music was in the late 1980s/early 1990s. There is an increasing sense among some segments of the Church that recognize the value of *chant* as the musical tradition of the Church, and there is a desire to return to the purity and spiritual beauty of traditional modes of church singing. Earnest efforts at English-language composition seem to be doing well. Indeed, I am reminded of the Tchaikovsky quote, “The rebirth of our church singing lies in the characteristic spirit of its ancient melodies with their stately, simple, sober beauty.”

And so, I am led to two questions:

First, how can we learn? Most of us cannot leave home to study with masters in Russia or wherever they may be. Most of us can’t even take off work for long enough to take a two week intensive course of study. The Byzantines have programs like the Greek Archdiocese School of Byzantine Music, the Trisagion School, etc., with fairly well-ordered curricula; between those and the recent(ish) book from John Michael Boyer, one can more or less learn the essentials of Byzantine music from a distance or as an autodidact. How can people learn the rich, beautiful tradition of znamenny chant? The execution of music always includes far more than notes on a page, so simply buying scorebooks as this database encourages more consistent composition probably isn’t sufficient—here, I am reminded of: the Ethiopian eunuch, “How can I [understand], unless someone guides me?” (Acts 8:31).

Second, is there any sense that a true revival of znamenny music—whether as a passage into some hypothetical future “American Orthodox” system of music or as something that grows and bears fruit without being changed into something “American”—would bring with it a return to using neumes/знамёна/stolp notation? From what I’ve been told, there is more communicated in the neumes than in square notes or Western staff notation.

Costas, you make several good points in your comment above. The history of znamenny chant vis-a-vis Russian culture is perhaps more complex than the relationship between Byzantine chant and Greek culture. In Greek lands there was not as long a period of “displacement and oblivion” as occurred in Russia, with nearly three centuries when znamenny chant was supplanted by Western-style harmonic singing. It did not help that the “New Direction” in Russian Orthodox church singing, which was blossoming and just beginning to bear fruit in the first two decades of the 20th century, was summarily shut down by the Communist Revolution in 1917. But seeds were planted nonetheless, and singing in many Slavic and Slavic-origin parishes (including those in the New World) is quite different today–much more “chant-aware” than it was, say, 100 years ago.

You are correct in your observation about the neumes, that they contain more information about the execution of the chant than simply pitch and duration. Fortunately, there are some people who are actively investigating and transmitting that information, including some in this country, like Old-Ritualist musicologist Nikita Simmons, who has recently become aware of our project and has expressed interest in being a part of it. (See our discussion following my post on Facebook, if you have access.) The prospects of such a collaboration are very exciting!

Are we talking about a wholesale rejection of harmonic part-singing and a return to unison znamenny singing? I think not. But one may hope that we will become much more aware of the capability of well-composed *melody* (whether sung in unison or with ison or in some form of counterpoint and harmony) to lend expression to the sacred texts of our worship and thus to communicate the tenets of our Orthodox Faith more effectively.