Similar Posts

Recently, iconographer Aidan Hart published the thought-provoking essay “Hand and machine: Making liturgical furnishings”. Mr. Hart’s piece is part of an ongoing exploration by liturgical artists of the question of how technology has changed, and is continuing to change, our relationship to crafts that have up until recently been done by hand. Liturgical designer Andrew Gould has also contributed to this conversation, as has woodcarver Jonathan Pageau. Each artist acknowledges the concern that mechanization and industrialization will in some way diminish the physical quality, the craftsmanship, and the spiritual value of liturgical art, and also force our liturgical aesthetic from an ideal of heavenly worship that is unique and personal into the realm of kitsch, of the cheap and prefabricated, of cookie-cutter monotony. Is everything doomed to follow the trajectory of the icon, where inexpensive laser printer renderings are mounted on wood, and the handpainted image is so rare as to have near-unicorn status?

The consensus appears to be that as long as technology is used as a tool to enable, rather than replace, the human craftsmanship, and does not overwhelm the creativity and specificity of the art in question, then there are ways of using technology that are practical and cost-effective without bringing down the quality. Sometimes it may even work well to adapt design to modern technology rather than continue to ape forms that have become disconnected from the function — that is, new technology may offer a way to rethink a given function, rather than resorting to skeuomorphism, where we maintain the outer appearance of a design element while removing its structural or functional significance, such as retaining the shape of a film camera, designed to accommodate the space considerations for a roll of film, with a digital camera that has different space considerations. (Skeuomorphism, I will note, is a somewhat ironic word to disparage, given that τὸ σκεῦος is the Greek word given to the holy vessels of the altar, which are stored in the σκευοφυλάκιον, lit. “where the vessels are guarded”.) Mr. Hart gives the example of a choros chandelier he designed, in which ultimately employing electric candles to preserve a visual design element made less sense than using concealed LED strip lighting at the base of the piece. The objective with employing technology ought to be, according to Mr. Hart, to preserve the sense that liturgical craftsmanship is “an act of communion as an act of creation”, and “to discern the logos or divine word of each created thing… We are called to bring out all the material’s potential[.]”

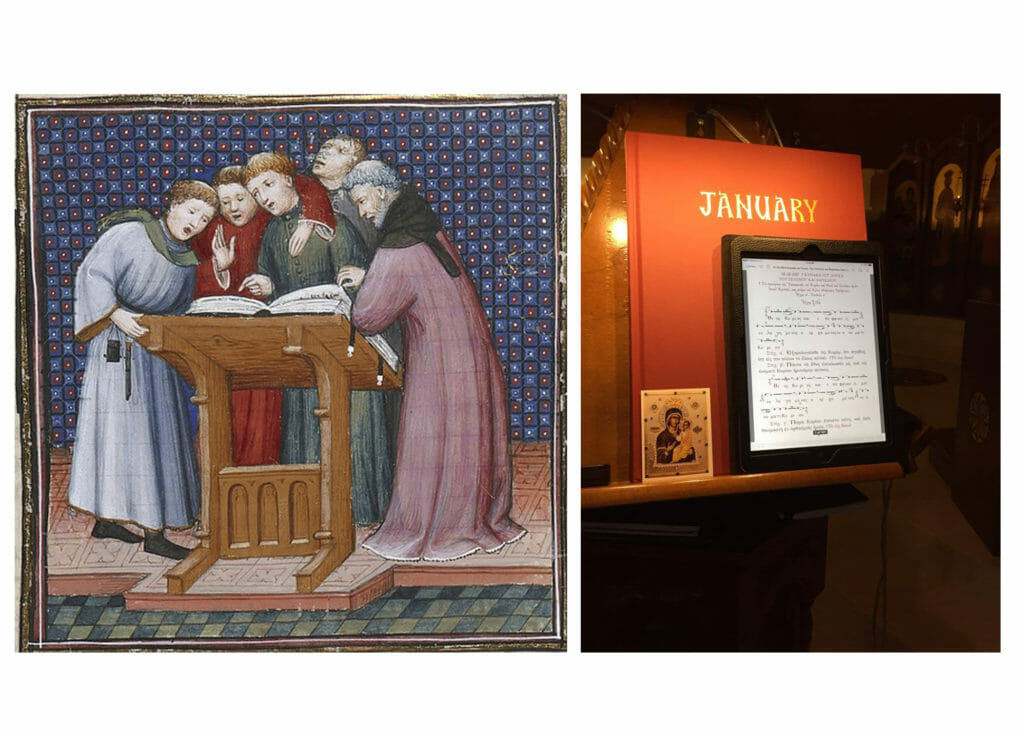

Music is a liturgical art that also has to examine these issues. Singers are old hands at having to adapt to technological developments; we’ve had to deal with the transition from the scroll to the codex, from rote memorization and improvisation to the development of music notation, from the manuscript to the printed book. In the last century, we have dealt with the impacts of the invention of the microphone, the rise of audio recordings, the ubiquity of computers, the permeation of all spaces and objects by the Internet, digital typesetting, digital synthesizers, and now the near-universality of the tablet computer and the PDF (portable document format). We interact with the architecture, the furnishings, the vestments, and the books, and we do so performatively. It is our job to make the words heard in a particular way; anything that enhances or decreases our ability to perform this task, or somehow accompanies us in doing so, changes our job to some degree.

Take the microphone, for example. Prior to its invention, singers and speakers had to rely on the natural acoustics of the building enhancing a cultivated skill of projection in the voice. That works well in Orthodox churches built with high vaulted ceilings and marble floors and curved apses serving as resonating chambers; Hagia Sophia’s decay time, according to the Stanford University Icons of Sound project, was approximately eleven seconds when it was full. Once there’s a microphone, though, that kind of natural acoustic, while still ideal, is no longer a need-to-have; neither is vocal training for that matter, for either speaker or singer. It is no coincidence that both of those factors are expensive — certainly far more expensive than a microphone, even a halfway-decent sound system, and any level of musical education. It is also no coincidence that in the twentieth century, architects started building churches that were intentionally dry acoustically, so as to favor the spoken voice as rendered by a microphone (such as St. Thomas Episcopal Church in New York; eventually they changed their mind and retrofitted the ceiling for a more forgiving acoustic). Not only that, but recordings, a technology enabled by the microphone, by definition preserve only those performances somebody thought worth preserving. As those performances get propagated as models to follow, it both has a homogenizing effect and rather elides the inevitable politics of performance practice. As recordings maintain the idea of a particular standard while the realities of electroacoustic technology mean the singer no longer has to produce the voice in a particular way to be heard in a big church, over time an ever-bigger wedge gets driven between normative performance practice and the ideal. To say nothing of the problem of technological “mission creep” as the money spent on it justifies an expanded use; the parish that spends thousands of dollars on a sound system for its temporary space will have a financial incentive to maintain its use in a permanent space rather than spend more money on a design that offers proper acoustics.

And then, for the small parish community wanting a more present sound for festal occasions, perhaps there is the temptation to use a recording to augment, or even replace, the human being at the analogion. A parish I once chanted for floated exactly this proposal for Holy Friday one year, expressing the concern that one person leading the Lamentations wasn’t going to yield the robust singing from everybody that would have been nice – maybe I knew of a CD that everybody could sing along to? (I declined. It went fine.)

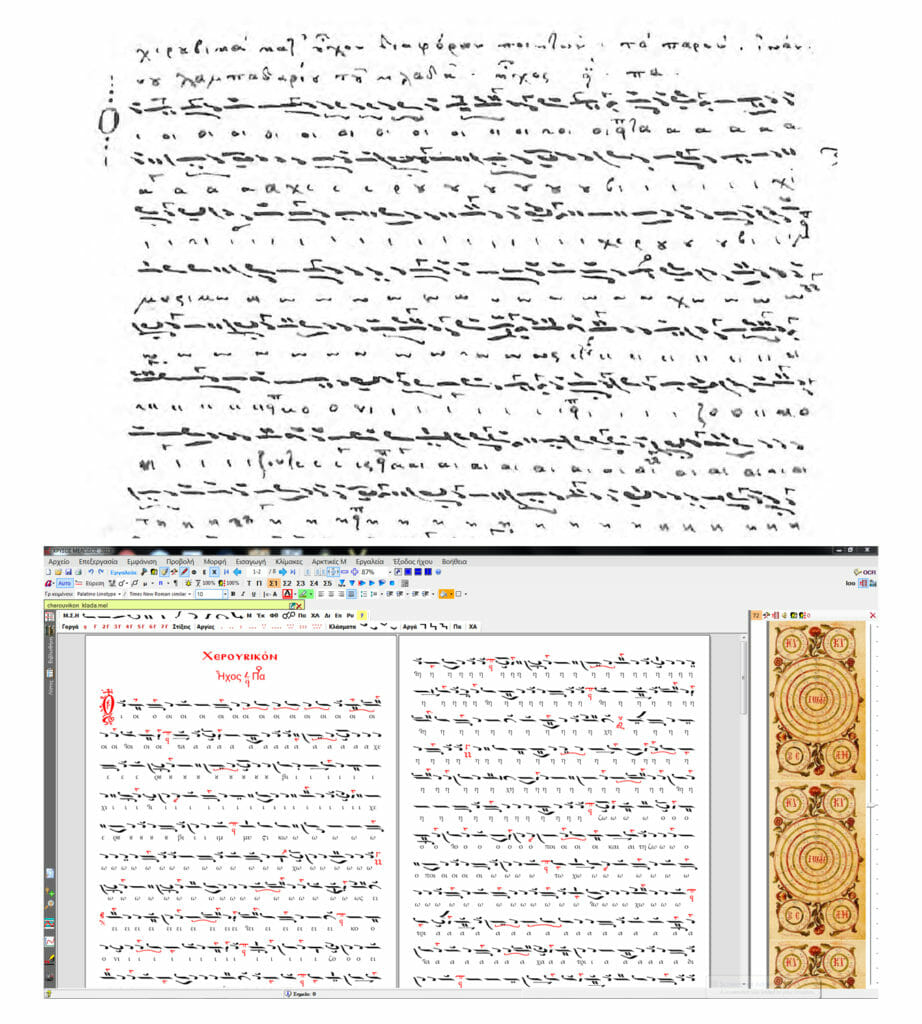

On the other hand, the computer, the internet, and the PDF have made some kinds of musical instruction possible across geographic barriers that would have been insurmountable before. Need a score from a Greek book that’s been out of print for over a century? Somebody’s probably posted a scan of the book in an online forum someplace. (Too hard to read? It’ll take maybe 15 minutes to retypeset it digitally.) Want to learn how to conduct a choir and you live in, say, Wyoming? You can take lessons over Skype from a master teacher in Russia. Having trouble getting Byzantine intervals in your ear? There’s an app for that. The freewheeling nature of PDF distribution via backchannels perhaps somewhat elides copyright issues for present-day translations and newer compositions, but since nobody in North America is exactly getting rich off of Orthodox music publishing, nobody is terribly concerned about that quite yet.

A manuscript copy of a medieval Byzantine Cherubic hymn contrasted with how it looks being digitally typeset. Typesetting by Phillip Phares; image used with permission.

To be sure, the pedagogical advantages of this technology have their limits, and must be employed responsibly. The easy dissemination of information does not void the necessity of human guidance; if anything, it makes a teacher even more necessary. You cannot teach yourself to be Orthodox, and you cannot be a church musician who is 100% autodidact (any more than you could be a priest who is completely self-taught). The web may make a great deal of information easily-available at the touch of a button, but a person is still going to have to help you navigate it.

Another example of technology empowering but also requiring discernment and responsibility is the tablet. Over the last five years or so, the tablet has been an amazing resource for every kind of musician, and it has changed the way we interact with and think about scores. As pianist Wu Han told the New York Times’ Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim (over Skype, no less) for a 2016 article, “It’s not like the old days where you only have information passed down by a teacher. Now everyone is a detective.” For Orthodox church musicians this means we can carry an entire library of liturgical books, sheet music, and even manuscripts in one portable, lightweight device. It puts much at one’s fingertips that might have been difficult to access otherwise, and where one Matins service may have required six or seven fairly bulky books, it can now be done all from one book-sized tablet. A library of public domain PDFs can be had for next to zero upfront costs (save for the tablet) and requires no storage space to speak of; this can be a real boon for a singer at a small parish with no budget for music and no room to store books.

On the other hand, while this may be a wonderfully empowering tool from a practical perspective, there are certainly concerns that the use of such devices has raised. Fr. Maximos Constans, a faculty member at Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology as well as an Athonite monk and accomplished scholar and translator, has taken a strong stance against tablets, saying that “A liturgical book is a sacred object, an iPad is not.” The issue is one of the tablet being a temptation to distraction, or worse, at least as much as it may be a practical tool, and generally being a multi-use object rather than being a dedicated sacred vessel. Other concerns have to do with it facilitating too much choice — that is, it being too easy for the individual musician to “roll their own” in terms of texts and music, as opposed to having a prescribed book with the preferred translation or settings of a given parish or jurisdiction. Some might raise the objection that the ability to navigate the physical liturgical books — Menaion, Oktoechos, and so on — is part of the discipline. At a price point of up to several hundred dollars, tablets could be seen as exclusionary in terms of cost, and an overreliance on an electronic device as introducing an unnecessary potential complication.

Nonetheless, various jurisdictions and para-ecclesiastical organizations have begun to embrace this kind of technology, perhaps starting the process of adapting the form to the function enabled by these devices. The Antiochian Archdiocese has rolled out an updated liturgical guide with embedded hyperlinks to sheet music PDFs; this is explicitly intended to streamline the process of using tablets and other smart devices for cantors and members of the choir, as well as to simplify issues of musical access for those who may not be certain where to find what they need.

AGES Initiatives, an extra-ecclesial nonprofit founded with the blessing of Metropolitan Alexios of Atlanta has the objective of using technology “to store, organize, and deliver Orthodox Christian liturgical texts and music to support the education of church singers, and to facilitate the smooth performance of church services”. (Statement of disclosure: this author is an employee of AGES Initiatives.) While commonly associated with the translations and compositions of its founder, former Athonite Fr. Seraphim Dedes, the AGES platform is first and foremost a database and distribution system that is library-neutral. In cooperation with the rightsholders for given translations, the database now includes the work of Fr. Ephrem Lash (including John Michael Boyer’s metrical adaptations), Fr. Peter Virgil Andronache, Fr. Juvenaly Repass, and also the St. Athanasius Academy Septuagint and the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese’s new official Divine Liturgy translation.

The publicly-available version of the AGES platform employs an algorithm that automates the process of applying the Violakis typikon to the liturgical library, generating the Digital Chant Stand — electronic bilingual service booklets with hyperlinked scores for all hymns in both languages, producing several months’ worth in only a couple of minutes. The platform is customizable for any typikon, any given library of texts, any library of music, and the booklet format is also customizable.

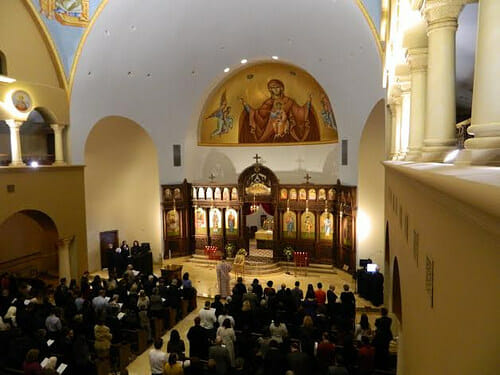

The AGES platform can be accessed through either the web or a tablet app that makes everything for any given service immediately accessible, but the system finds its fullest expression in something much more intentionally disruptive: the fully-implemented Digital Chant Stand, as currently found at Fr. Seraphim’s home parish of St. Nektarios Greek Orthodox Church in Charlotte, North Carolina. All skeuomorphisms are done away with: the analogia have been removed, and there are no books. A/V carts loaded with computer and audio hardware occupy the very traditional spots of left and right choirs in front of the solea, and antiphonal choirs of men and women gather around large computer screens, on which a mouse click pulls up a PDF for every piece of music in the service. This is, to be sure, a tool with considerable application in the mission field beyond North America; for example, the Archdiocese of Kenya has officially adopted AGES for its liturgical texts and rubrics.

Of course, there are concerns. As a character in the classic 1982 science fiction film TRON warns about artificial intelligence, “Won’t that be grand! The computers and programs will start thinking, and the people will stop!” An understanding of rubrics and how to perform a service according to the typikon from the books themselves is part of the church musician’s job, it might be argued, and fairly. On the other hand, none of the jurisdictions have made it a priority to translate the typikon; there have been personal efforts that have been published through various channels (including both draft copies made available digitally and actual physical books), but nothing formal. There are reasons the North American jurisdictions have not made this a priority; allocation of resources, and presumably concern over pastoral application of such a document were it to be universally available, just to suggest a couple of possibilities. Be that as it may, the truth of the matter is, for the Anglophone world — and more broadly speaking, the mission field — there is no direct access to the typikon, and services still need to be offered in the meantime. As for working from the liturgical books themselves, the practical consideration is again one of cost and space for the smaller and/or newer parish (or even jurisdiction, as seen with the example of Kenya).

There are practical concerns of a skeuomorphic nature. With no physical books, customary practices involving them — such as the placing of the Triodion before the icon of Christ right before Vespers of the Publican and Pharisee — become problematic. As noted, having antiphonal A/V carts that look like nothing so much as portable recording studios right in front of the solea is a visual disruption in the midst of iconography and woodwork. Here, I would return to the matter of Aidan Hart’s choros chandelier that embraced concealed LED lighting as an adaptation of form to a new manner of function. In the same way, these issues represent challenges that are properly the domain of a designer; how might an artist such as Mr. Hart or Andrew Gould design an analogion intended for the function of the Digital Chant Stand that would preserve, perhaps even expand, a traditional aesthetic?

If Andrew Gould, the designer of this analogion, were to create a design for the Digital Chant Stand, what might it look like?

There are a couple of elephants in the room that have been only briefly alluded to, and those are the closely related issues of economics and convenience. Design elements that favor natural acoustics, to give but one example, are expensive; marble — or even wooden — floors, high ceilings, plaster construction, and the like all make for a wonderfully resonant church, if you can afford them. And, because those elements arguably make the physical experience of being in church more austere (particularly the floors), some communities may be reluctant to justify the expense. I’ve been there when parents of small children have said it’s unrealistic to expect them to have their kids crawling around on such a floor. “Why do I want to stand on a rock hard surface like that for three hours or more at a time?” somebody once told me. Acoustics were one issue, I suggested; “Yeah, well, in this day and age it’s called a microphone,” was the response. For better or for worse, the relative economy of amplification thus allows the nonstandard space to become standard.

On a smaller scale, books, music, and standard liturgical furnishings associated with cantors and choirs also run into barriers of cost and convenience. There is one English-language Menaion available, it alone is a $1,200 investment, previously-alluded to issues of typikon mean that even if a church has them there is no guarantee that anybody will know how to use them, and as I know from my own experience, if there is not a standard analogion, the individual volumes are extremely cumbersome to have open on a common Manhasset black music stand. If you want to buy the Greek books, the volumes perhaps cost half as much, but as they have to be imported from Greece, shipping brings the price back up. And yes, a standard analogion and set of stalls will themselves run into the thousands of dollars, if you can even find somebody who knows how to build them for you. A few hundred dollars for a tablet that then has all of the necessary liturgical texts and music loaded on it for free, or even for a nominal subscription fee, starts to look like better bang for the buck for parish communities with limited resources, as well as a more practical adaptation to the pastoral realities of a mission field that does not have the backing of an imperial treasury.

This piece has only allowed for a surface analysis of the various issues I’ve raised; much more can be said, and it is my hope that these observations might generate fruitful discussion. The way technology interacts with liturgical music has changed dramatically just in the last ten years. The best way to adapt remains an open question. Still, to return to the consensus of Messrs. Hart, Gould, and Pageau, we need to be vigilant that technology is used as a tool to enable, rather than replace, the human element inherent in our practice of singing praises to God, and that it does not overwhelm the creativity and specificity of how we do it. Perhaps, in adapting form to the function of new technology, much as had to happen when the scroll became the codex, this adaptation will give way to something that is beautiful and in keeping with our tradition in its own right. It will be up to designers and musicians to collaborate in faith and find the point of intersection between technology, practical reality, pastoral application, and tradition where we may bring out all the material’s potential.

Thank you for the article Richard!

it has given me much to think about and to discuss with our small mission community Church.

We have one woman who valiantly with no training uses AGES as her practise tool to lead us at the liturgy and has been joined by 2 others. However problem still remains for us how do we get the music right?

Whilst I can “spiritualise” it by saying we are giving the angels something to do as they carry our worship to heaven that doesn’t satisfy the hunger of us to have a way of improving our worship.

I have mixed feelings about the objections to “tablets”, part of me says yes it can never be a “holy object” if it is also used to surf the net etc but the other side of me says that if it used purely for liturgical purposes then it can indeed be a “holy” book.

Again thanks for a very thought provoking article.

In Christ

Fr Paul

I am not sure that entirely buy into the “book as a sacramental” in and of itself. I have a full collection of liturgical books in my home library that are largely used more for reference than they are for home worship, since I transcribe the text to arrange music around for Church. My preference at Church as been to use books, but for scores that would otherwise be used only for that service and only printed as loose sheet music, I have steered more towards using the ipad because of economy and logistics.

This article is very difficult for me. As a choir director myself, I can certainly appreciate some of the practical conveniences addressed here, but I can’t help but feel an intuitive aesthetic disgust of where this is heading.

We must be careful of making assumptions about which elements of our religion are important and which are not. For instance, there is the assumption that singing the correct texts is important, but that having them printed and bound in a beautiful book is not important. Likewise, that the ascetic discipline of arranging those books on the stand, and finding the right pages quietly and with liturgical dignity, is not important. And that the intense beauty of an analogion illuminated by a small warm lamp, whose color matches that of candlelight, is not important.

Who has the authority to say that these small things are dispensable – that they are not among the important elements of our religious inheritance?

The use of the microphone reflects a similar problem of judgement – an assumption that loud, understandable vocalization is important, but that the natural beauty of the unamplified human voice is not important. Why? It strikes me as erroneous logic, which, if taken to its natural conclusion, would lead us to listening to professional recordings rather than live music in church.

But I should specifically address the question asked of me in this article – how would I, as a designer, handle a digital analogion? I would first say that the aesthetic language of everything in a church should be consistent. Therefore, if we are generally committed to Byzantine architecture and its associated palette of materials and details, then it is not appropriate to have an overtly modern machine-aesthetic analogion. It will undermine, rather than support, the whole, even though it has an internal consistency, even beauty, of its own. The design integrity of the whole is more important than the design integrity of the parts.

So I would not change the design of the analogion at all – it would still be good traditional wood furniture, and the tablet would simply sit on the music desk, replacing the printed book in the least disruptive way possible. Any associated computer equipment would be hidden away.

As for the tablet itself, I, personally, would find the glow of a typical screen to be an intolerable imposition on the liturgical aesthetic. These screens command all our attention, focusing our vision there alone, pulling us through a window into a another realm of existence. We all know the frustration of conversing with someone continuously glancing at an iPhone, as opposed to a printed book. The attention-consuming characteristics of a glowing screen are fundamentally different from printed paper. So I don’t see how choristers could sing from a glowing screen while also maintaining an easy mindfulness of the service going on around them.

On the other hand, a non-glowing screen, like that of a Kindle, illuminated by a traditional incandescent lamp or candle flame, would not be so bad. That I could tolerate.

I appreciate your points, Andrew; my question is, how far do we want to take the preference for a beautiful bound book? A preference for a calligraphic manuscript on vellum bound in leather? A preference for a scroll? I’m being serious. Was some version of this conversation had when liturgical/music book production moved from the monastery to the printing shop?

In terms of the ascetic discipline of handling books — yes, I agree. On the other hand, implicit there is the assumption that there are books, they are available, and if it weren’t for tablets, people would learn said discipline. Depending on what you’re talking about, this is not a safe assumption to make. For example, if Byzantine chant is what you do, then the Greek books have to be imported; there are, as yet, no English-language books printed, not yet. Most cantors I know who chant principally in English have to work from PDFs either downloaded from platforms like AGES or distributed in samizdat-fashion via a network of people who know people. If you chant any in Greek, you probably have a judicious selection of books that you either bought in Greece or invested in having imported (I should also note that, generally, cantors have to buy their own books), and then you generously supplement from PDFs of scores that are distributed, again, through the chant social circle. It is commonplace now, not just via platforms like AGES, but also through other channels, for service-specific PDFs to be generated with scores embedded in them, so that you just need that PDF and nothing else for a given service. Where do the scores come from? Often they are images cut-and-paste from PDFs of the books themselves, or they are from a database of digitally-typeset scores created just for this purpose.

And, the thing is, the American jurisdictions have, by default, created this situation. They have, in the main, not made it a priority to create or publish quality liturgical books or music books. The printed books that do exist are not without their problems, and while there are newer efforts (such as Benedict’s lovely publication), it’s been expensive and endlessly iterative just to get where we are now. Most individuals are not in a position to self-publish beautiful, bound books, and the economics of doing so for Orthodox music do not make it particularly interesting for commercial publishers. Different jurisdictions for some time now have distanced the singer from the actual books by focusing on “liturgical guides” and whatnot rather than teaching singers the Typikon and how to use the books. (This has had the additional impact of enforcing a set of preferred cuts to various services by simply not telling people that there are cuts. A recent example is the complete omission of any mention of singing “By the water of Babylon” during Matins on Triodion Sundays in the various liturgical guides that are out there.)

All of this is to say, the message from the top down has been very plain that the supplying texts and rubrics has been the practical concern, the specifics of publishing books are not an area where they feel they can put their resources, and so it has been up to musicians to come up with their own solutions. I suppose we can like it or dislike it, but it’s what is happening. I think that eventually books will be more available than they are, but until then, there are limited options.

This is why I suggest that “enabling rather than replacing” is a useful guideline; technology making it possible for somebody to carry a complete music library with them is enabling, but using a recording to replace a singer is, well, replacing.

As for “mindfulness” — well, the New York Times article suggests that the tablet is becoming a common tool at all levels of music-making. This seems to me like an adjustment that people are already making.

Andrew Gould, I want to preface my response to your remarks and this artilce with the points that: (1) I have never used a tablet in church; (2) once or twice in desperation due to a missing text that was found on line and distributed to singers via email/SMS, our choir actually sang briefly from hand held devices and it worked out OK; and (3) I recall nostalgia for raggedy hand-copied texts when they were replaced with neatly printed, computer typeset scores… that didn’t mean the rag-tag slips of yellowed paper were necessarily better.

And yet part of me longs for church to be a screen-free zone, and low-to-no tech. We all need a break from the endless stream! Yet, with even bishops wielding smartphones inside the altar, it seems that there is no avoiding the tidal wave.

There is a lot to digest here. But, what I really wanted to say is: I like your sense of aesthetic.

p.s. to the publisher: what happened to the link for “but since nobody in North America is exactly getting rich off of Orthodox music publishing” … I wanted to see what the author had in mind there! I’d say, only a few make any money at all off of sacred music publishing, and for most of us, it’s an endeavor that costs (but reaps rewards that are not pecuniary).

Is the link not working? If you’re having trouble, try this: https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/orthodoxyandheterodoxy/2013/01/29/the-hidden-hand-behind-bad-music-could-it-happen-here-american-catholic-worship-and-orthodoxy-in-america/

Thank you for speaking up, Andrew. You are not alone.

I am blessed to be a reader at a parish whose priest observes the full unabridged cycle of daily office and services – with every day of the week Orthros and Vespers, including full text of the canons and kathismata (from the Holy Transfiguration Monastery books).

I can verify from my experience that there is something about a piece of paper that keeps you ‘in the room’ in the way that a traditional icon does. Whereas an illuminated screen takes you out of yourself and out of the room in a similar way that innovations in liturgical art from the renaissance on did so. So, PLEASE … keep printing those PDF’s y’all.

And artificial amplification of the voice is an imposition on the spiritual space of our fellows. It is akin to raising one’s hands above the heads of those around us in a gesture of prayer. It’s not bad per se; it’s just very much not the ideal.

If we don’t notice that we are imposing on the spiritual space of our brethren, then we are not doing the primary job of a reader/chanter, which is to listen. Give more energy to listening than than to enunciating.

One last point (which now, I’m putting on my crazy end times prepper hat) is that by trusting the archive and retrieval of all of our services to the digital realm, we as the church make ourselves vulnerable to hard times to come. A set of decades-old books in every parish is much more resilient to flood, famine, earthquake, the sword, foreign invasion, and civil war than a centralized cloud-based sequence of 1’s and 0’s. Let’s think about that before we dismiss the expense of bound books as an unrealistic investment.

I agree that dismissing the expense of bound books as an unrealistic investment is unwise. That’s not what I’m saying. There is nonetheless a state of affairs such that the jurisdictions have not, by and large, made it a priority to make such books available. Materials produced by HTM and AGES, while at the opposite ends of a number of spectra in terms of approach, fill a vacuum. I, as an individual cantor/choir director, am not personally going to spend $1,200 on a Menaion set that does not even employ the register of English my bishop prefers; that leaves me with few options.

Do you know that you can buy a complete set of analogion-size liturgical books (Menaia, Triodion, Pentecostarion, Psalter, Orologion, Apostolos), in Greek, published by the Church of Greece using the Church of Greece’s text, for maybe $200-250 at most? That’s because the Church of Greece has made the investment in making them available. That has not been taken on by any canonical jurisdiction in North America. What we have now, in its various forms be it HTM or AGES – fills that void; it’s what’s available.

And that doesn’t even get into the question of *music* books.

I’ll cut and paste here from an earlier comment that nobody has really engaged:

In terms of the ascetic discipline of handling books — yes, I agree. On the other hand, implicit there is the assumption that there are books, they are available, and if it weren’t for tablets, people would learn said discipline. Depending on what you’re talking about, this is not a safe assumption to make. For example, if Byzantine chant is what you do, then the Greek books have to be imported; there are, as yet, no English-language books printed, not yet. Most cantors I know who chant principally in English have to work from PDFs either downloaded from platforms like AGES or distributed in samizdat-fashion via a network of people who know people. If you chant any in Greek, you probably have a judicious selection of books that you either bought in Greece or invested in having imported (I should also note that, generally, cantors have to buy their own books), and then you generously supplement from PDFs of scores that are distributed, again, through the chant social circle. It is commonplace now, not just via platforms like AGES, but also through other channels, for service-specific PDFs to be generated with scores embedded in them, so that you just need that PDF and nothing else for a given service. Where do the scores come from? Often they are images cut-and-paste from PDFs of the books themselves, or they are from a database of digitally-typeset scores created just for this purpose.

And, the thing is, the American jurisdictions have, by default, created this situation. They have, in the main, not made it a priority to create or publish quality liturgical books or music books. The printed books that do exist are not without their problems, and while there are newer efforts (such as Benedict’s lovely publication), it’s been expensive and endlessly iterative just to get where we are now. Most individuals are not in a position to self-publish beautiful, bound books, and the economics of doing so for Orthodox music do not make it particularly interesting for commercial publishers. Different jurisdictions for some time now have distanced the singer from the actual books by focusing on “liturgical guides” and whatnot rather than teaching singers the Typikon and how to use the books. (This has had the additional impact of enforcing a set of preferred cuts to various services by simply not telling people that there are cuts. A recent example is the complete omission of any mention of singing “By the water of Babylon” during Matins on Triodion Sundays in the various liturgical guides that are out there.)

All of this is to say, the message from the top down has been very plain that the supplying texts and rubrics has been the practical concern, the specifics of publishing books are not an area where they feel they can put their resources, and so it has been up to musicians to come up with their own solutions. I suppose we can like it or dislike it, but it’s what is happening. I think that eventually books will be more available than they are, but until then, there are limited options.

This is why I suggest that “enabling rather than replacing” is a useful guideline; technology making it possible for somebody to carry a complete music library with them is enabling, but using a recording to replace a singer is, well, replacing.

Thank you, Richard.

I have mixed feelings about all of this, actually. I have been helping as best I can to acquire some sort of access to each of the available liturgical books for the choir at our OCA parish, including the real books when possible (Violakis Typikon from the Metropolis of Denver, Saint John of Kronstadt Press books, Saint Polycarp Press books, Holy Transfiguration Monastery books, General Menaion from Father John Peck, Antiochian Liturgikon, Hapgood, OCA Archieratikon, Mother Mary’s books, &c., &c.), but also some digital stuff that I have found to make up for bare spots. But in all honesty, they are nearly just eye candy for liturgical-minded individuals at our parish because we basically use OCA music from across the last fifty years, and we have binders for different services. The director needs to know how to use the “abridged typicon” that the OCA puts out each year, but that’s it.

In our small parish situation, regarding the tablets, my personal “ten-year plan” is to somehow utilize a tablet and create an app that replicates our binders, giving access to our director to adjust them as he sees fit, but otherwise just making page finding easier and preventing the loss of music (such as in a flood, which we have already experienced). Also, backlighting is just simpler sometimes, especially with some weaker eyes trying to see music in a dimly lit Church during Great Lent or Holy Week. As long as a warm light filter can be applied, it also doesn’t mess as much with the ambience of our Church.

Nevertheless, things can go wrong, and so I know the liturgical books should not be abandoned. I would much rather use the books, honestly, but a 20-person choir cannot read from one set of books, and having a library for each person to use is obviously impractical on many, many levels.

Thankfully, we do without microphones, but our parish has been retrofitted and is does not welcome resonance. I find it interesting that most of the Church structures that I have seen built for amplification tend to be the ones where clergy utilize electronics most, by the way.

Anyway, great points to ponder as we continue our trek into the future of Orthodox singing…

This very conversation (specific to tablets / using AGES and similar) came up in a conversation with a hierarch this past weekend. He was largely opposed because of issues you’ve mentioned, specifically:

1) the convenience of AGES (as well intentioned as it is) has enabled both ‘laziness’ and sort of a blind-adherence to what’s provided (to the exclusion of all else either because what I am handed must correct and I wouldn’t know how to even begin to question it – i.e. if I even wanted to verify that the content is accurate how would I do so? – or due to lack of education about possible modifications or variances in the typikon in particular parts of the service). I personally am someone who has just enough liturgical vocabulary in Greek to where I can read through the hmerologion published by the Patriarchate and, if needed, put a service together from the catalog of books. Fr. Seraphim is certainly not trying to enable ‘laziness’ but any materials need to be used in the ‘right hands’.

When I have attempted to teach people who are interested in chanting, I always begin with (or shortly after the beginning) a discussion of the liturgical books required to put a service together. This may not not be wildly exciting to everyone but it absolutely (in my opinion) HAS to be taught before giving into “okay thanks, now can we please sing something?” One key reason for this is that there is, in most chant choirs, a role assigned where an individual is charged with preparing the books. This person should know the order of the service and what books are needed because the singers, even if the books are near at hand, will not always have time to pick up the next book and find the right page in a timeframe that doesn’t disrupt the service. So the books need to be ready to be used on an as-needed basis in the moment.

2) The iPad/Tablet as distraction. I think there are easy ways to solve this. 1) The parish can invest in several tablets (older models that are used and refurbished that are less expensive may be purchased in secondary markets – the need to read PDFs arguably does not require the most up-to-date processing power, though at least a current OS to be able to handle the most up-to-date viewing applications perhaps would be). When people see demonstrations of software on tablets or, if you’ve ever gone to an office and checked in using a tablet, this tablet is only enabled to run that specific application. As such, it is likely that there exists some kind of administrator software that would restrict usage of the tablet to only specific applications and access to specific applications (i.e. social media) and specific websites could be restricted. Implicit in this however, is that the person using the tablet has a minimum competency in rubrics and music. I’m not sure otherwise that there’s much difference between giving someone with lack of training a tablet or giving them a book. If they don’t know how to navigate that book, or sing what’s in it, what’s the difference?

Other than addressing the glow of the tablet which Mr. Gould brought up, I believe there are solutions to the above

As to the ‘rolling one’s own’ with respect to musical choices, it is likely in many cases that the chanter/choir director knows more about what’s available with respect to music for a given piece/service than the priest does (although this is changing as more priests-in-training are learning the ins and outs of music). Moreover, it’s been my observation that choir directors are not in the habit of pre-clearing most music with their clergy (though this is just my experience and may not be the case everywhere, of course). As such, regardless of whether that music is printed or handed out or used on a tablet, the problem is the same. If clergy wish to have some opportunity to vet the music being selected for services, then that’s a chance for the choir director/chanters to discuss with the priest what’s available, and explain why they want to use what they want to use – but that’s not a problem of printing vs. tablets (we could have athonite music, music from the patriarchate, music from chanters from Thessaloniki, transcriptions from the old teachers…lots of choices out there).

At the same time, I would like my priest to trust that I 1) have good taste and trusts me (though this needs to be earned) and 2) that if I wish to sing, say, a version of a Holy Week hymn by Theodosopoulos instead of Petros Peloponnesos that I have the ability to make that call. If a priest has the knowledge and conviction to say “no, we use only Petros for Holy Week” then alright, but that’s certainly the vast minority of priests. The selection of music is generally in the domain of the choir director / head chanters and having such a position should imply that trust in taking on those duties has been given by the priest.

If the existence of tablets has caused consternation among certain individuals and caused them to pay more attention to what’s happening musically then I would say this is overall a good thing, to the extent it is now helping to take something that was once marginalized and making it more top of mind.

[…] recent article by Richard Barrett in the Orthodox Arts Journal called “Voice and machine: Technology and Orthodox Liturgical Music” got me thinking about a lot of things, but one of the comments by Andrew Gould has really stuck […]