Similar Posts

I have survived three pilgrimages with Fr. Ilya Gotlinsky, leader of Orthodox Tours. Each one has been a sermon. My journey through Macedonia, Kosovo and Serbia (May 25 to June 7, 2014) with 27 fellow pilgrims from the Australia, England, Ireland, Russia and the United States, is the latest sermon.

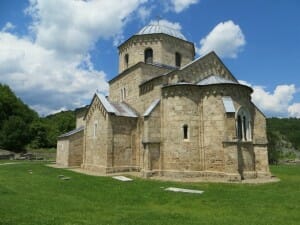

Our pilgrims climbing to the Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, near Novi Pazar, part of Stari Ras complex. The oldest intact church in Serbia, it was founded in the 4th century during Roman rule.

First Sermon: Russia 2005, “Beloved, behold your future”

Somewhere along the road from Suzdal to Yaroslava a deserted church on the eastern skyline called to us. As our bus drew nearer we could see hundreds of blackbirds roosting in the skeletons of its cupolas and wild brambles growing on its roof. It was not on our itinerary, but we turned aside to explore this grave of prayer with graffiti scaring the lower surfaces of its unremarkable fresco. Fr. Ilya climbed up on a mound of trash in the altar area and declared, “Beloved, behold your future!”

Somewhere along the road from Suzdal to Yaroslava a deserted church on the eastern skyline called to us. As our bus drew nearer we could see hundreds of blackbirds roosting in the skeletons of its cupolas and wild brambles growing on its roof. It was not on our itinerary, but we turned aside to explore this grave of prayer with graffiti scaring the lower surfaces of its unremarkable fresco. Fr. Ilya climbed up on a mound of trash in the altar area and declared, “Beloved, behold your future!”

Second Sermon: Mount Sinai 2008, “Blessing from Prophet Moses”

During Emperor Justinian’s reign in the 6th century, a monk of St. Catherine Monastery completed the 4,000 rough granite steps of Sikket Saydna Musa (the Path of Lord Moses). In the mixed company of a thousand spiritual and eco-tourists from all over the world, I reached the summit of Mount Sinai at sunrise on October 21, 2008. My descent was not so simple.

The first time I fell, a young Bedu offered me his hand. As he pulled me from the ground, he extended his other hand to receive a wage. The second time I fell, I heard a sound like a dry twig snap in the wind − a compound fracture of my right ankle − tibia, fibula and medial malleolus. Hoisted on a camel by two strong guardians of Musa’s Mountain for transport to St. Catherine Monastery below, I would thereafter walk with limp – my “blessing from Prophet Moses,” Ksenia Pokrovsky called it.

Third Sermon: Serbia 2014, “Bombs were useful”

It is rare that strangers are welcomed into the private cell of a monastic. But there we were, our group of iconodules, crowding into the bedchamber that doubles as the painting studio of Mother Efimija, abbess of Gradac Monastery in southwest Serbia. Herself, a fine iconographer, she had abandoned a promising career as an artist to devote her life to prayer.

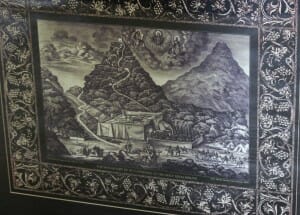

A lithograph of St Catherine Monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai hung on the wall beside her bed.

“Have you been there,” I asked?

“I’ve climbed it twice and I hope to do so again.”

It was there in Mother Efimija’s studio that the third sermon for this pilgrim began, though it would take 12 days of travel through the history of the Balkans to hear her say, “Bombs were useful”.

Macedonia

We began our survey of the ancient and medieval monasteries of the Balkans in the capital city of the Republic of Macedonia, Skopje, whose foundations can be traced to 4000 BC. Stomping ground of Philip II Macedon and his son Alexander the Great, and birth place of Byzantine Emperor Justinian, it has been called the “city of seven gates.” Skopje was a major crossroad for the Greek and Roman empires in succession with commercial and military highways leading southeast to Asia Minor; northeast to Kievn-Rus; southwest to Rome; and northwest to Europe.

After touring the monasteries around Skopje and viewing their exquisite fresco, we wended our way to Lake Ohrid. Evangelist missions of St. Paul are believed to have reached these shores in the first century. In the 9th century, St. Clement together with St Naum of Preslav established a great ecclesiastical center and scriptorium on Lake Ohrid where Christian learning and art spread from Constantinople to the Bulgarian and Slavic people.

St. Clement and St. Naum were the most prominent disciples of the brother saints, Cyril and Methodius, Enlighteners of the Slavs. It is at Ohrid that the first students of the Glagolitic alphabet, the basis for Cyrillic script, produced copies of scripture and liturgical books translated into what is now called Old Church Slavonic.

The labors of these pioneering evangelists and those of the many saints and martyrs of the region are recounted in the “Prologue of Ohrid” compiled by the Serbian saint, Nikolai Velimirovic (1881-1956).

Church of St. Panteleimon at Ohrid, physical reconstruction completed in 2002. The original 9th century structure was severely damaged in 15th century by the Ottoman Turks who used it as a mosque.

St. Sophia cathedral church of the Ohrid archbishopric was constructed in 893 on the foundation ruins of a Christian temple built as early as the 4th century. Adornment of St. Sophia began in 1040 and the surviving frescoes are considered some of the best and largest theological compositions in any Byzantine cathedral church of that period.

While in the vicinity, we visited the Gallery of Ohrid Icons where some of the highest examples of Byzantine artistic genius from the 11th through 14th centuries are housed. Among them are two large, double-sided processional icons created in the imperial workshops of either Constantinople or Salonica for the Cathedral of St. Sophia in Old Ohrid citadel.

The processional icons were rescued from Ottoman vandalism when St. Sophia was converted to a mosque in the second half of the 15th century. Removed to the Church of the Mother of God Peribleptos, which by necessity became the cathedral church of the Ohrid archbishoporic during Ottoman conquest, the processional icons appear in nearly every publication of Byzantine art. Meeting these masterpieces at breath’s distance was like a reunion with old friends. We could hardly bear to leave their society.

Processional icon of the Annunciation, early 14th century (reverse, the Mother of God Psychosostria) from the Church of the Mother of God Peribleptos, St. Clement, Ohrid.

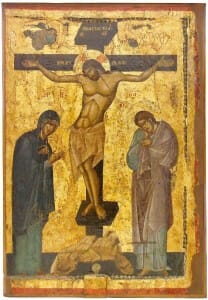

Thirteenth century processional icon of the Crucifixion (reverse side, the Mother of God Hodigitria), Church of the Mother of God Peribleptos (St.Clement, Ohrid).

And this was just day two of Fr. Ilya’s masterfully planned agenda of Balkan treasury. Leaving Ohrid, May 27, on route to St. Naum Monastery on Lake Prespa, we traveled through the great Galičica Mountain pass where hang-gliders sported above its cliffs.

From St. Naum we went “off the beaten path,” in Father’s words, to the remote village of Kurbinovo in search of the former Monastery of St. George. St. George Church was built during the first reign of Emperor Isaac II Angelos of Constantinople and fresco painting began in 1191. The work is considered a high mark of Byzantine art produced in Macedonia, in fact, in all the Balkans.

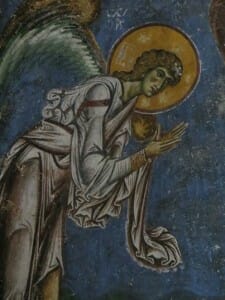

As our driver maneuvered the back roads and steep ridges, Fr. Ilya prepared us for astonishment with the story of his stalking an angel he had seen in photographs of Balkan art. Misdirects, disappointments and persistence on previous journeys finally rewarded him eureka in the foothills of Baba Mountain. As promised, his angel whose image is printed on the Macedonian 50 denarii, astonished us.

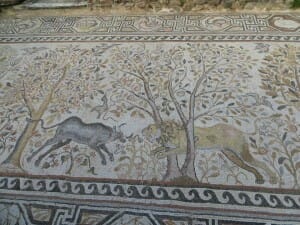

Making our way to Prilep in south central Macedonia, we stopped at the Archaeological Park of Heraclea Lycenstis, a city founded by Philip II in the 4th century BC. Heraclea was an important point along the Via Engati the Romans built in the 2nd century BC, connecting Dyrrachium on the Adriatic Sea to the ancient settlement of Byzantium, the future East Roman capital of Constantinople. Archeological digs at Heraclea are ongoing, revealing spectacular mosaic floors of the city’s Christian basilicas that were active between the 4th to 6th centuries.

The only way for us to view these wonders was to transverse the four-foot high perimeter of the basilica’s crumbling foundation. So determined was I to see their glories, I got in the one-way line of more agile pilgrims before realizing that my “gift from Prophet Moses” could have ended my adventure on day five and caused great inconvenience to my friends. It was then that our remarkable guide, Ivan Krucican (more about him later), realized that this old goat required extra shepherding, if goats can be.

Our exploration of Stobi archeological site in central Macedonia did not require as much planned footwork to view the well-preserved mosaic work. Especially inspiring was the 4th century baptismal font.

Kosovo

By day nine I had squeezed off more than 300 shots of the 10 monasteries and churches visited before June 1 when we reached the Kosovo checkpoint. Grim-faced Albanian gendarmerie boarded our bus to collect passports and stare long at each pilgrim’s face to match identities. Though we had passed through the mosque-dotted countryside of Macedonia and seen the devastation the Ottomans had dealt their monuments, the reality of Christian struggle to survive 10 centuries of Islamic conquest caught up with us and produced a great silence in our wheeled apartment.

Since 2001 Serbian enclaves and historical sites in Kosovo have been under the international military protection of NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR). An Italian brigade in Armani-designed uniforms currently represents KFOR in the area. Our itinerary cautioned, “Please note that in case of the slightest political disturbance in Kosovo, we will remain in Macedonia and offer an alternative plan for sightseeing.”

Three times our driver lost his way in the city of Kosovska Mitrovica after sundown in the rain. GPS instruments were useless because streets with Christian names have been changed and signposts defaced with “UCK,” the Albanian language acronym for the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). Finally, at the concrete barricaded bridge over the Ibar River separating Muslim controlled south city and Serbian north, our driver gave up and called our destination hotel for assistance.

We enjoyed cheerful Serbian hospitality at our hotel that night and hearty Jelen pivo (beer). Next day, we set out to view three of the most significant monasteries of historic Serbia: the Church of the Theotokos at Gracanica Monastery constructed in 1321 by King Milutin on the ruins of an earlier temple dedicated to the Theotokos, which itself was built on the 6th century ruins of a three-nave basilica; Holy Ascension at Visoki Decani built by King Stephen between 1327 and 1335, which has the largest preserved deposit of Byzantine fresco art in the Balkans; and the temple of the Holy Apostles in the medieval complex of the Kosovo Patriarchate at Pec.

I became a subscribing supporter of Decani Monastery during the late 1990s when NATO began bombing raids to assist the Albanian take over of Kosovo. Daily, I checked for posts from Fr. Save (Janjic), fearing grave news or loss of contact with the monks as Muslims destroyed more than 150 churches and monasteries in Kosovo and Metohija. Despite appeals to President Clinton from Orthodox hierarchs in North America and Serbian-American citizens of the U.S., NATO bombing of Serbia commenced on the Feast of the Annunciation (March 25, 1999), and continued through Holy Week. On Pascha morning, April 11, NATO bombs with “Happy Easter” scribbled on their casing were dropped on Belgrade bridges and other strategic targets. In February 2008 the United States under President George W. Bush formally recognized Kosovo as a “sovereign and independent state” governed by Albanian partisans.

We tasted no bitterness in our hosts, though emphatically reminded, “Kosovo is Serbia!” Her Jerusalem, her heart, where Prince Lazar laid down his life on the Field of Blackbirds in 1389 to defend his children against the invasion of Sultan Murad I. Twice, the Ottoman Turks had failed to conquer Constantinople (1411 and 1422) before changing strategies to subdue the surrounding Byzantine territories: the Balkan kingdoms of Albania, Bosnia, Croatia, Hungry, Montenegro, Serbia, and later Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania. After making the Balkan kingdoms his vassal states, Sultan Mehmed II was finally able to launch a successful breach of the Walls of Theodosius on Tuesday, May 29, 1453.

With evidence all around of redoubled Islamic determination to re-conquer the Balkan nations, which as a combined force had thrown off the Ottoman yoke just prior to the outbreak of World War I, we became witnesses of the soft-invasion overwhelming Christian populations and laying waste their holy sites. I was reminded of why I had decided to take my third pilgrimage with Fr. Ilya. It was his words when I hesitated to commit, “Mary, you must hurry!” But it was also the memory of his 2005 sermon from the mount of ruble in an abandoned church on the road to Vologda, “Beloved, behold your future!”

Serbia

We entered Serbia proper on day 10, June 2.

Church of Archangel Michael, Monastery of Crna Reka tucked away in Ibarski Kolašin gorge on the Black River.

Our program included the great ecclesiastical center of Sopocani Monastery built by King Urosh in 1265; the Monastery of Crna Reka (Black River); and the Pillars of St. George (Djurdjevi Stupovi) endowed by King Stefan Nemanja l in the 12th century. St. George Monastery is dear to me for the videos produced through the efforts of the abbot, Fr. Gerasim, who we briefly met. These wonderful videos raise awareness of Serbian Orthodox culture and hopefully funds for the rebuilding of St. George, constructed in 1170 and largely destroyed by the Turks in 1722.

The video for Pascha is enormously popular in the U.S., and my favorite, the joyful (must see) behind-the-scenes production of their Nativity offering. Engaging the talents of Serbian musicians and superstar Divna Ljubojević, both videos feature the poetry of St. Nikolai Velimirovich of Ohrid and Žiča set to popular Serbian melodies.

In 2004 KFOR troops (the fashionably Armani-vested Italian guard) asked the abbot to stop renewal of the monastery and remove the rebuilt roof because it “irritates the local Albanian Muslims”. In the spirit of Serbian resolve, yet, in even deeper devotion to the Orthodox faith, he continues to strengthen the youth of the region to resurrect St. George.

By the end of day 11 we were dizzy with the vastness of Byzantine art and architectural bequeath to the Serbs: the great monasteries of Mileševa where St. Sava’s relics were enshrined until the late 16th century; Zica Monastery founded by St. Sava as his archbishopric headquarters; and Studenica, the largest and most richly endowed monastic complex in Serbia.

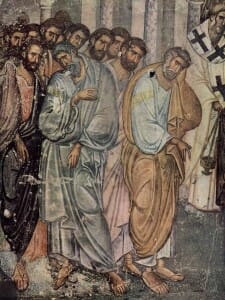

We were a caravan of church art enthusiasts, four priests and 11 practicing iconographers acquainted through photographs with these famous frescoes that have survived plunder, early and late. Coffee-table reproductions cannot make one so dizzy as crooning the neck to meet Gabriel, the “White Angel” of Mileševa Monastery and the “Blue Angel” of St. Achilles Church, or the thousands of portraits of prophets, saints and martyrs from sacred history that fill the walls and ceilings of every church in the Balkans.

Righteous Abraham. Father of Nations: fresco from St. Nicolas monastery near Prilep, in the village of Manastir on Mariovo Mountain, Macedonia. Built in 1005 by Alexius, the cousin of the Emperor Alexius Comnenus.

Gradac Monastery

It was on day 12 (June 2) that antique treasure met fresh. We traveled along the Gradacka River on the Ibar highway, which connects Belgrade with Skopji and links to Montenegro via the Adriatic highway. Our guide pointed out a bridge over the Gradacka where heavy fighting in 1999 took place between the Serbs and the KLA assisted by NATO intervention.

Our destination was Gradac Monastery built in the 13th century with an endowment from French-born Queen Helen d’Anjou, wife of Serbian King Urosh I and mother of kings Dragutin and Milutin.

Gradac lies at the edge of the forested slopes of Golija Mountain. During Ottoman rule its roof was destroyed in the 17th century. A protective roof was built in 1910 and complete restoration of the church structure as a cultural landmark was undertaken from 1963–1975 under Tito, the communist dictator of Yugoslavia. Construction of monastic living quarters began in 1982. Abbot Julian Knežević (1918–2001) revived Gradac as a female monastery.

Though the original dome was blasted away by Islamic siege in the 17th century, Queen Helen’s composition for the stone iconostasis was mostly preserved in its primary provenance. In place of the icons Queen Helen sponsored were newly painted works that, while in keeping with tradition, had a distinctly contemporary grace. Their delicate line-work and airy palette, suggestive of feminine decision. Queen Helen had found her aesthetic heiress, but who was she?

After viewing the interior of the temple, we were invited for tea with the prioress on the porch of the nuns’ quarters overlooking the grounds of Gradac Monastery.

Two-plus decades ago, Jasna Topolski, a graduate of the Belgrade Academy of Fine Arts who had become a famous artist, believed that art would direct her to truth and resolve the mystery of death. “But I found no answers,” she said in a 2011 interview with Egypt’s “Daily News.” Not until she turned to the church did she realize where to find “the complete answer.” Jasna learned icon painting and left the artsy distraction of Belgrade for the solitude of Golija Mountain where she began re-adorning Helen d’Anjou’s long neglected temple. In time several artist friends followed her in the monastic way and today she is Mother Efimija, Abbess of Gradac Monastery and its 12 nuns.

The iconographers and I were filled with curiosity about Mother Efimija’s work we had just seen on Queen Helen’s iconostasis.

“Would you like to see our studio?”

Up three flights of stairs we wound to the laboratory where students progress through beginning, intermediate and advance stages toward becoming working iconographers in demand, not only throughout Serbia but also in Croatia. I was affirmed that our classes across the Atlantic correspond so closely with the nuns’ lessons in panel preparation, pattern drawing and pigment application. “The more we paint, the more the icons seem to be elusive,” Mother Magdalina, the principal instructor of the studio is quoted in the same Daily News of Egypt interview. “We can never say ‘I have mastered the technique of painting icons’.” How like Kseina Pokrovsky’s dictum!

The best was yet to come when Mother Efimjia invited us to her own studio on the second floor. It was not what I saw there that I will remember for as long as I live. It was the conversation I had with Mother Efimija, prompted by my surprise at finding an etching of Mount Sinai beside her bed.

“Have you been there?”

“I’ve climbed it twice and I hope to do so again.”

Instant identification.

All the way through Macedonia, Kosovo and to this coordinate at Gradac in southwestern Serbia, we had seen the Ottoman’s legacy of devastation that left stumps of roofless churches and Christianity’s biography in fresco marred. I was ashamed that countries such as mine have so recently participated in their destruction. I wanted to apologize to someone, to ask the forgiveness of a priest at Decani Monastery or some waiter who served us Jelen in a Serbian restaurant. Since NATO bombs had rained down on the nearby bridge across the Gradacka River, Mother Efimija seemed the perfect witness to hear my unorthodox confession.

With her back to me as we descended the stairs, she responded to my regrets, waving her hand as if swatting a fly, “Bombs were useful.”

Everyone in the downward queue heard her words and wondered, as I did, what doses she mean?

“What do you mean, Mother,” I asked when reached the porch?

“God allowed it. We were not frightened when bombs fell around us. We had to think, if God allows this, what is good in it since God is good? There is always something in us that He is showing us by what He allows. Not only showing us but also showing those who drop bombs. Because of this we cannot blame anyone.”

Why do Christians go on pilgrimage? I can hardly think of a holy destination I have visited that has not been desecrated in the past or is at present time being desecrated, whether by religions that abjure Christianity in particular or secular atheists who oppose all religion.

Everywhere along my on/off decade of pilgrimage, I have seen defaced temples and toppled gravestones that have their rebuilders. The churches and monasteries of the Balkans, no less than those of Russia and the Levant, have undergone seasons of destruction followed by times of restoration only to be destroyed again, and rebuilt again. Abbot Gerasim who is building up the Pillars of St. George is not moved by objections that it “irritates” destroyers. Neither did bombs frighten Mother Efimija and her sisters.

St. Sava Church, Belgrade

We ended our journey in Belgrade on June 7 at the great Church of St. Sava. It is constructed on Vračar plateau in the center of the city where Sinan Pasha ordered St. Sava’s relics to be burned on Holy Thursday, April 27, 1595. Having brutally suppressed the uprising of 1594 when Serbs carried banners of St. Sava’s icon into battle, the grand vizier had the saint’s relics removed from Mileševa Monastery to this site and the defeated populace herded here to witness the incineration. The symbolism of this day in Holy Week for Christian people was not lost on the pasha, or was it, for it commemorates not only the institution of Holy Eucharist at the Last Supper and Christ’s agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, but also His betrayal by Judas.

Patterned after Hagia Sophia in present day Istanbul (fallen Constantinople), St. Sava ranks among the ten largest church buildings in the world. But if you ask a Serb, the largest, and not out boasting. It is larger than its model on the Bosporus and by worship space greater than St. Peter Basilica in Rome.

Planning for the temple began in 1895, three centuries after the burning of St. Sava’s bones. The most venerated saint of the Serbian people, St. Sava was born Prince Rastko Nemanjić, the youngest son of Grand Prince (King) Stefan Nemanja, founder of the Nemanjić dynasty. In 1192 Rastko went on pilgrimage to Mount Athos where he was tonsured the monk Sabbas. Rejecting his father’s appeal for his return to assume royal leadership, the young monk sent a message to King Stefan, “You have accomplished all that a Christian sovereign should do; come now and join me in the true Christian life,” which the king did in 1195 to become the monk Simeon. St. Sava did return to Serbia in the early 1200s as the first archbishop of the autocephalous Serbian Church. St. Sava planted many churches and monasteries throughout Serbia, including Zica that became his archbishopric seat and the coronation church of Serbian kings.

Plans for St. Sava temple were interrupted by the First World War, during which 1,100,000 inhabitants representing more than 27% of Serbia’s overall population and 60% of its male members, perished. Not until 1935 was construction of St Sava begun with the laying of its foundation. Stalled again in 1941 by the opening of the Second World War, building efforts were not renewed until 1985. By 2009 the structure of the basilica was completed, saving the adornment of its interior that still waits funding. Like Hagia Sophia in Istanbul the icons of St. Sava will be mosaic dressed. Target date for completion is 2016.

We were more than astonished by this new Hagia Sophia on the Danube. Her massive pendentives, protectively wrapped in heavy-ply plastic, support a height of 230 feet. She is 160 feet wider than a football (not fùtbol) field and 70 feet higher were the playing area pitched vertically. Her west to east expanse is a mere 60 feet less than a Super Bowl stretch.

As I prepared to say “goodbye” to my recent old friends, I got lost as I did in Christ the Saviour Church in Moscow (August 2005) when marveling the resilience of Russian Christians to rebuild the temple Stalin dynamited in 1931. I was not lost as Fr, Ilya thought then or as our guide Ivan Krucican thought on our last day in Belgrade, June 7. Under the great dome of St. Sava temple that promised to someday sparkle with millions of tiny glazed stones depicting the Panocrator, I knew not whether I was on earth or in Heaven. But I was certain that Sultan Murad had failed on Kosovo field in 1389; that Sultan Mehmed had failed on Tuesday, May 29, 1453 in Constantinople; Sinan Pasha had failed on Vračar plateau in 1595; and Stalin had failed in Moscow to prevail against the Kingdom of God.

I was lost in the sermon I had come to the Balkans to hear. Indeed, “bombs were useful” in quelling my bystander-bitterness over the misguided geopolitics of the last year of the 20th century that secured the annexing of Serbia’s heart, her Jerusalem, to her persecutors of 700 years.

The blank walls of St. Sava temple on which the believing remnant of Serbia has lifted the symbolic vault of heaven over Vračar plateau, like the white-washed walls of Hagia Sophia that Justinian reared by the Sea of Marmara in 532, are surety that there will always be builders and re-builders of Holy Wisdom until the Parousia of Our Lord. Because of this we can “rejoice and be exceedingly glad!” I had limped to Macedonia, Kosovo and Serbia, not merely to see the antique treasures of Byzantine art and architecture that are being threatened by the advancing energies of UCK, but to “behold our future” and not blame anyone for what God allows.

“Oh, Lord, save Thy people and bless Thine inheritance … and by the virtue of Thy Cross, preserve Thine habitation!”

Note about our guide: We spent two weeks with a young man, from my perspective, about whom we learned very little of his personal life. So professional is Ivan Krucican. Yet how many times we heard ourselves saying, “Ivan knows everything!” Touring with Ivan was like having a living encyclopedia of ancient, medieval and modern civilizations: their history, geography, economies, politics and art. Only on the last day in his home city did we learn about his profession as a researcher and lecturer at the Gallery of Frescos of the National Museum in Belgrade. As much as the bounty of Balkan art and architecture he showed us is an international treasure, so is Ivan Krucican a treasure to the world. God grant Ivan, his wife and his little sons, Many Years!

Beautiful, Mary. Well done and full of depth. Thank you.

Thank you, Mary, for that beautiful essay! Parts of it read like a beautiful prayer.

“Target date for completion is 2016.”

Then shouldn’t they be busier working on the church? Current pictures don’t seem to show much progress over those of 2 or 3 years ago.

Further, just because the nuns weren’t bothered by the bombs, doesn’t mean that many other suffered terrible.

There was a 3-year-old girl who had all her hair fall out from the terror, and a boy of similar age who stopped talking and became mute.

The tennis star Novak Djokovic said it was terrible and was particular hard on his mother and what it did to her. And you have others who still get nervous with the sound of even commercial aircraft in the air.

Not to mention those who were maimed and left permanently disabled. And all the women who had abortions at the urging of the health ministers after NATO bombed the Pancevo oil refineries and chemical storage units. They were also told not to get pregnant for 2 more years due to the threat of birth defects thanks to NATO’s poisoning. I don’t believe it’s the will of God, more like Satan loose and running free in the world – the NWO/neocons at the helm of power.

Not all Serbs can run off to climb mountains in a distant part of the world, so fact is that the nuns didn’t suffer as others. They are in one piece and are not living in a place threatened by Albanians — yet!!

I think some Serbs can be too forgiving or dismissive of what other Serbs have suffered – and it’s often come back to haunt them.

Thank you for your passionate comments.

First of all there are very little funds to finance the expense of mosaic for the completion of St. Sava temple. It depends upon donations. I think the target date is wishful thinking. I hope I am wrong.

Secondly, you rouse my bitter feelings again over NATO intervention during the 1990s. I am aware of the horrors of which you speak. I deplore them all! It was a risk in writing about Mother Efimija’s words, a risk that they would be interpreted as passive acquiescence to evil, even dismissive of evil. Living so close to the fighting as she and her nuns do, not on some far away idyllic mountain, they are carrying out the Gospel in a most earnest way by praying not only for the safety of Christians around them, but also for the Muslim population that threatens them. I cannot explain it any better. I am merely a reporter, not a disengaged reporter, but one actively and deeply concerned with the suffering of the Serbian and Macedonian Christian remnant. I did not mention that Mother also told us about some of the Albanian Muslims living near Gradac who have embraced Christ. Now that is real courage!

As someone who lived in the Balkans off and on for many years, this is a wonderful treat of a read, and it brings back lovely memories of the churches in the region, especially those of my beloved Skopje.