Similar Posts

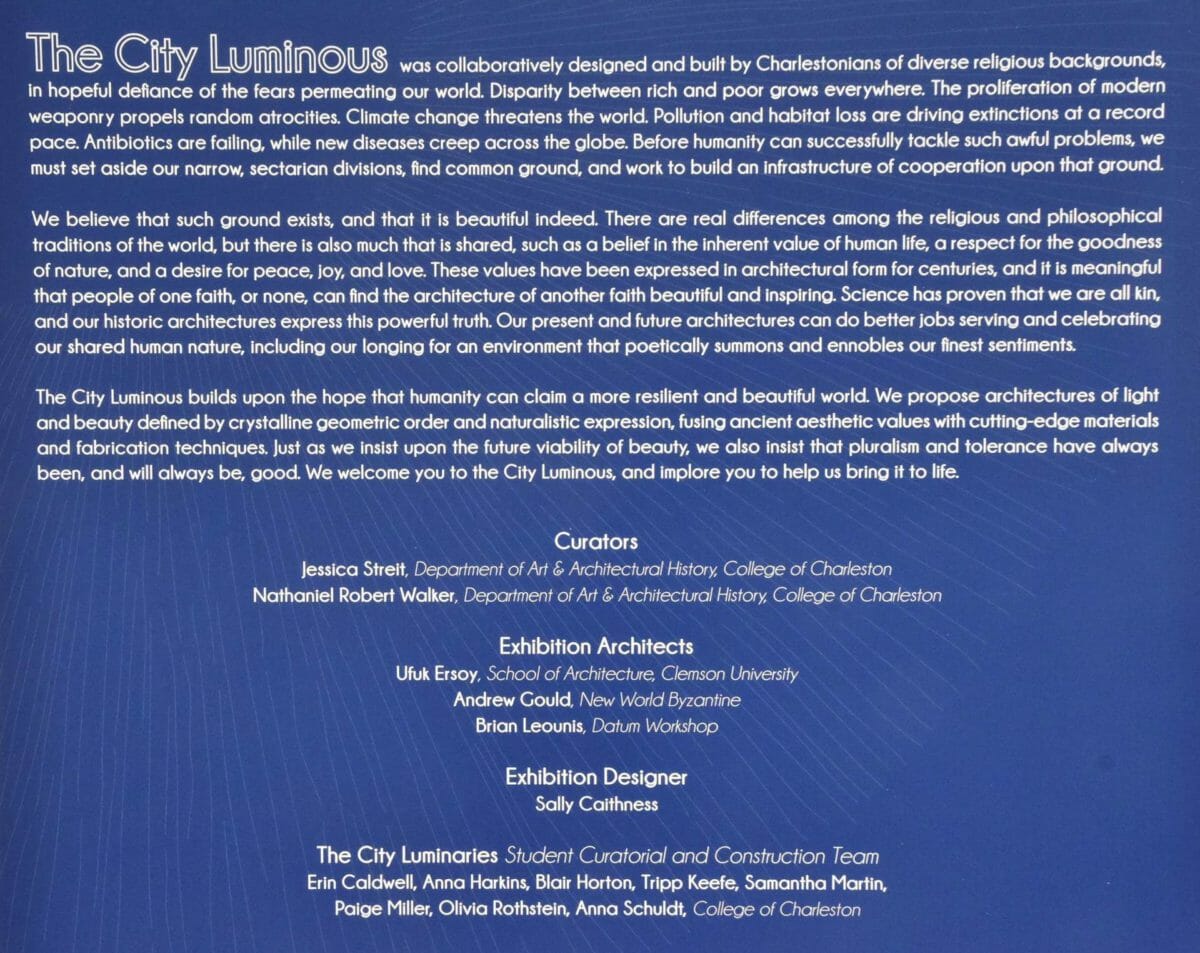

As a designer of Orthodox churches, it is unusual that my work would be featured in an art gallery. But just such an opportunity arose recently. I was asked to design the central pavilion for The City Luminous: Architectures of Hope in an Age of Fear, an exhibition on display this month in Charleston, SC.

As a designer of Orthodox churches, it is unusual that my work would be featured in an art gallery. But just such an opportunity arose recently. I was asked to design the central pavilion for The City Luminous: Architectures of Hope in an Age of Fear, an exhibition on display this month in Charleston, SC.

The show was conceived by faculty at the College of Charleston – a professor of Architectural History with a specialty in civic monuments, and a professor of Islamic Art. They wished to show an optimistic vision of the future – an architecture of traditional uplifting beauty, reflective of different religions living in peace. And they wished to show how modern technology (CNC fabrication) can help proliferate, rather than undermine, traditional beauty and ornamentation.

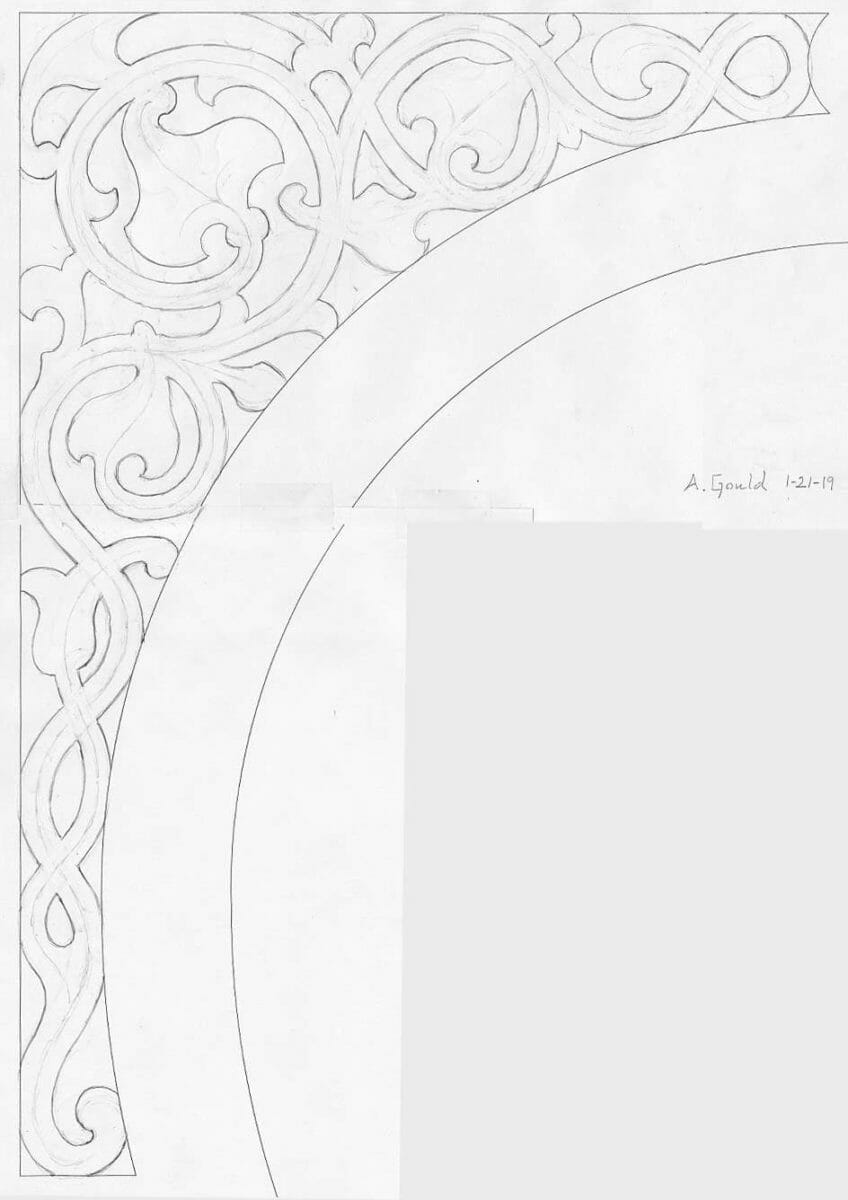

Although I had little part in formulating the vision and philosophy of this show, certain aspects of it aligned well with my own work and artistic interests. I have made extensive use of CNC technology in crafting my Byzantine chandeliers, and have a library of ornamental fretwork designs that I have adapted for this purpose. And being familiar with the Paradise symbolism in Byzantine and Islamic architecture, I knew how to design an installation that would express spiritual and material redemption. So when the organizers asked me to design the central pavilion for their show, I felt confident I could achieve what they wanted.

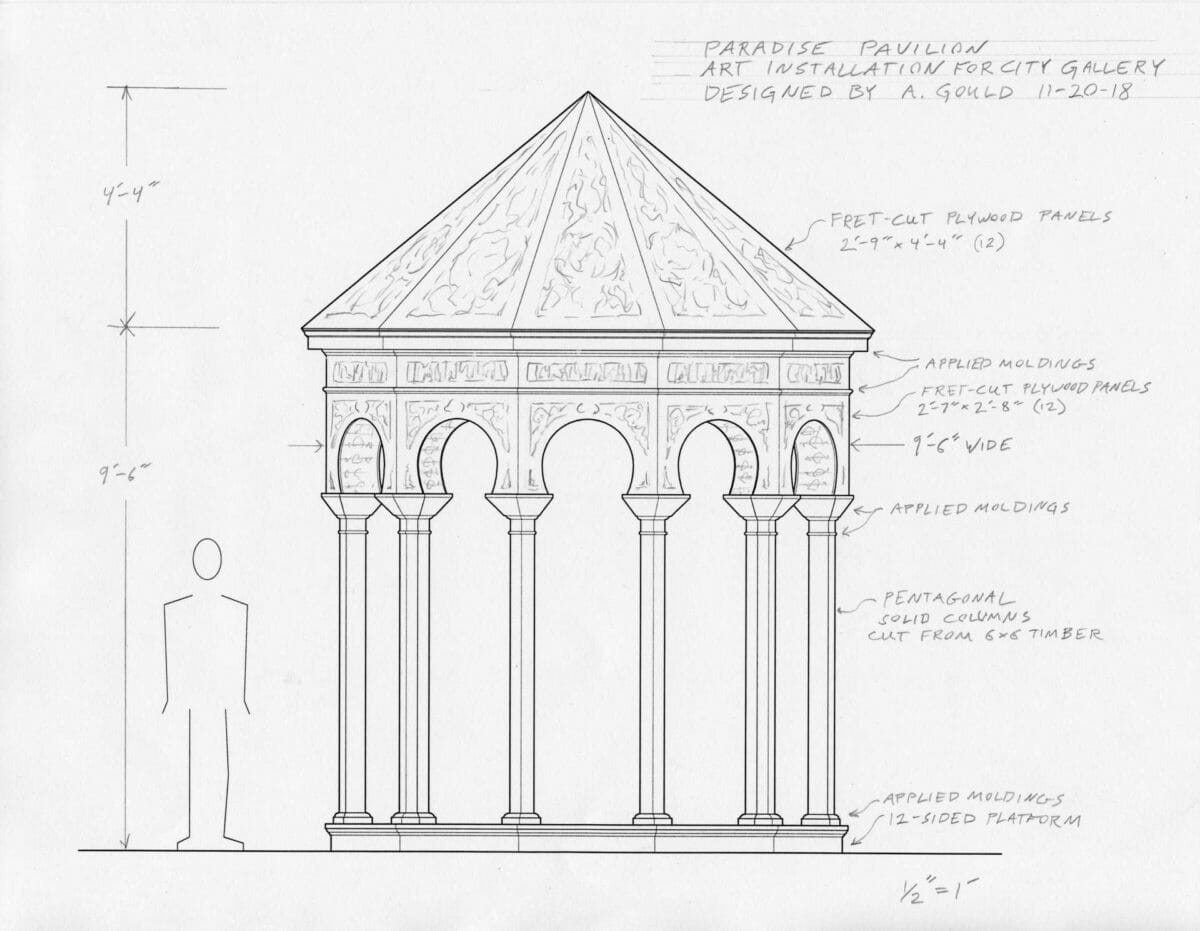

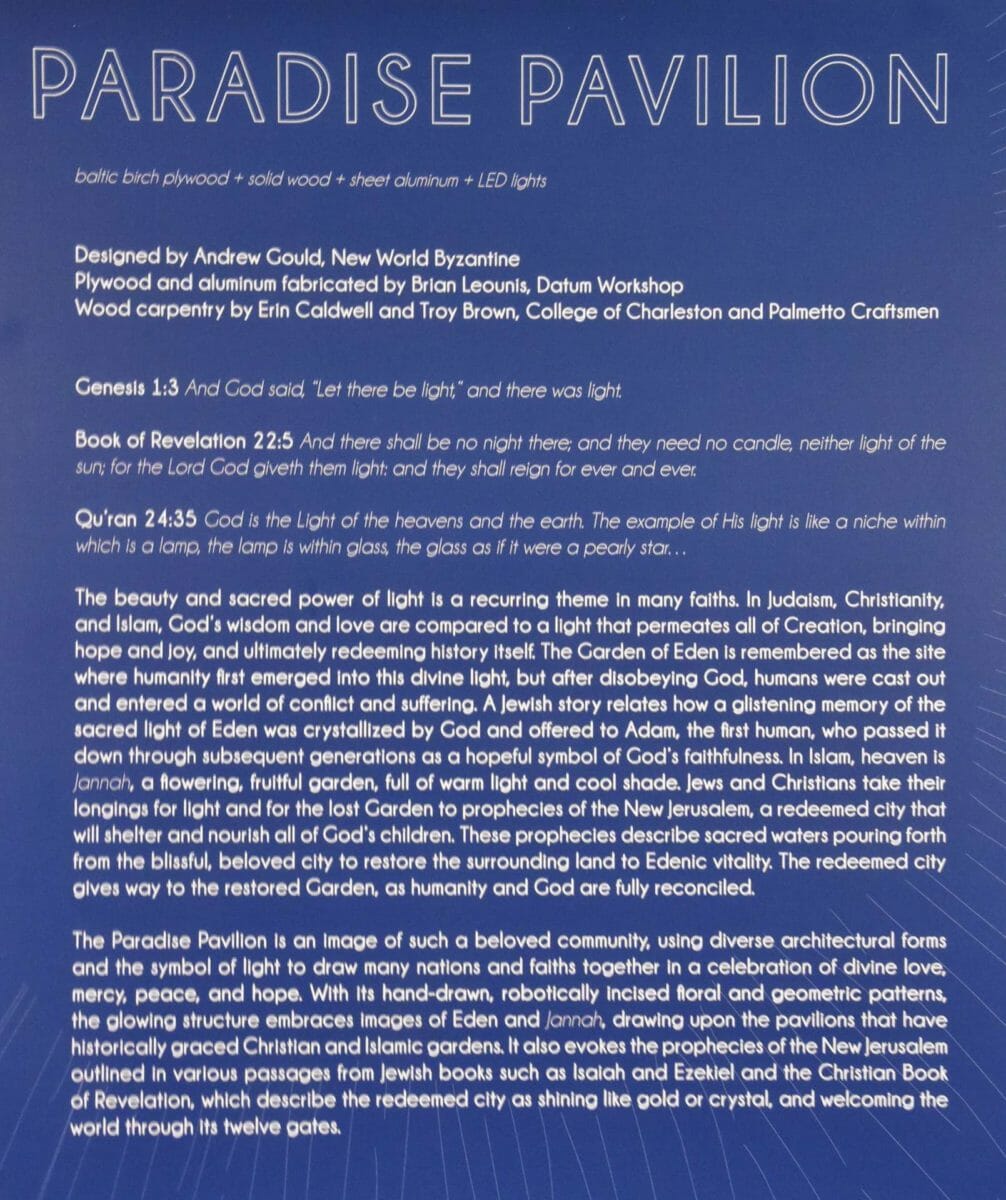

I decided that the pavilion should specifically represent the New Jerusalem. After all, the Heavenly City is the perfect image of redemption and harmony expressed in architecture. Every Orthodox temple is, in some ways, an icon of the New Jerusalem, and I was pleased to explore that symbolism in a new type of structure. I made it a twelve-sided pavilion, after the twelve pearly gates described in Revelation (for the twelve tribes to enter). Around the cornice is this inscription: “There shall be no night there; and they need no candle, neither light of the sun; for the Lord God giveth them light: and they shall reign for ever and ever.” (Revelation 21:5)

On the floor of the pavilion, I made a watery pavement with aluminum inlaid into plywood. I used patterns typical in Byzantine pavements – interlacing circles, like currents in the sea. On the ceiling I made a multitude of stars, like the dome of Heaven. In between are arches full of life – leaves, peacocks, lions – all the beautiful things of creation.

The symbolism of Paradise is no less developed in Islamic art than in Byzantine, and I freely mixed decorative patterns from both traditions, as well as ornamental moldings and architectural forms that derive from Classical Rome. I wanted to express both the exotic and the universal – all the things from far and near, gathered in Heaven.

There is plenty of historic precedent for Byzantine Christian motifs occurring in mosques (The Dome of the Rock) and for Islamic motifs occurring in churches (in Spain and Sicily). Nevertheless, in my church design, I would be quite hesitant to blend such things so noticeably. But for this pavilion, I was pleased to have a little more freedom. It’s a simple fact that no one did pavements as beautifully as the Byzantines, and no one did star-patterns as beautifully as the Muslims. So I used what works, and I made them work together, much as we see in medieval Spanish architecture, or in Russian churches, where Islamic influence brought the glories of onion cupolas and arabesque ornament into Orthodox art.

In order to finance my work on this project, the College of Charleston appointed me as the Quattlebaum Artist in Residence. The endowment for this position is meant to bring a practicing artist into contact with the students, through lectures and collaborative projects. As such, I was able to bring a group of students to Holy Ascension Orthodox Church, and present to them the beauty of Orthodox liturgical art. And I worked with them to help build the pavilion. Although the plywood and aluminum panels were fabricated by a professional shop with a CNC router, the structure had to be assembled completely by volunteers – faculty and students at the college.

Bringing my liturgical art into an academic milieu, and displaying it in a secular gallery space, has been an excellent experience. I have found the faculty and students to be enthusiastically receptive of everything I have to say, even when I explain things theologically, as only a believer would. Art history professors must, of course, maintain a certain objective distance from faith in their professional work. But a practicing artist such as myself, brought in as an artist-in-residence, is in a different position. In a sense, I and my work are as much an object of study as a tool for understanding. So I have the freedom to present liturgical art and symbolism from the standpoint of a practitioner – an Orthodox Christian working in an ancient tradition.

The pavilion is displayed in the City Gallery, a grand modern building owned by the City of Charleston. It faces directly onto the waterfront park downtown, which is always full of tourists enjoying the view of the harbor and Fort Sumter, where the Civil War began. It is interesting to watch the stream of visitors walk into the gallery and see the pavilion. They come expecting something cerebral and political, probably not beautiful. (How often does one see something beautiful in a gallery of contemporary art?) But the pavilion arrests them. It does not look old, and yet it is beautiful. It does not look political, and yet it seems full of meaning. They cannot quite see how it fits into this world. I hope it awakens in them some thoughts of another.

Excellent work. As a timber framer who has done a number of pavilions, it is a joy to see one done in a beautiful sacred manner. I am curious, are those posts triangular? and were those also done on your CNC or in some other manner?

Thanks. The posts and capitals are irregular pentagons. The posts are solid timber cut on a table saw. The capitals are glued-up plywood cut on a CNC router. I would have liked to do something more refined there, but it was built on a shoestring budget, so we could only manage so much.

Hah! It is amazing how much a budget can dictate a project. Thought, to be honest, I think that the capitals provided a good transition to the plywood arches. If you had done something more refined, I feel that the transistion from the solid post to the plywood would be to abrupt.

What a wonderful collaboration and beautiful piece of work. Thank you!

This is glorious. Congratulations on the project, Andrew. I may have overlooked it, but what is the pavilion’s eventual permanent home to be?

Also, how did you make the intrados of the arches? Are they machine-rolled bent aluminum plates, or are they a thin veneer plywood that could be bent by hand?

We’re hoping to find a more permanent space to assemble the pavilion, maybe in one of the College of Charleston’s buildings. We shall see it happens.

The intrados of the arches is 1/4″ bendable plywood. It fits into a rabbet cut into the backside of the arch panels.

It has now been announced that the pavilion will be re-erected in the rotunda of the Addlestone Library – the main building at the College of Charleston – from June until December. This will greatly expand its exposure.