Similar Posts

Cover ofThe Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting( A Facsimile of the 1887-1888 Shanghai Edition), PrincetonUniversityPress.

Truth is truth wherever it is found. In fact, it is all the more delicious when found in unexpected places. I was at the opening of an exhibition of The St John’s Bible, for which I had been one of the illuminators, and fell into conversation with one of the professors at Minnesota University. We talk about parallels between Chinese art and icon painting. I had long suspected there was overlap between the two art forms, and he kindly offered to send me a translated copy of the classic work, ‘The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting’.[i]

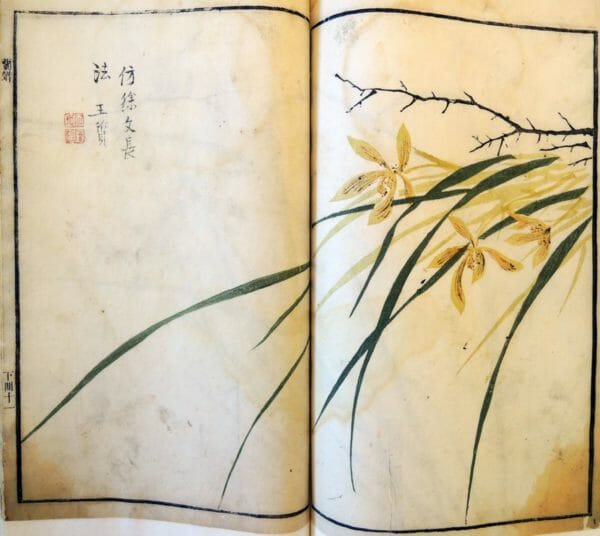

“Lotus Flower”, a page from The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting. Part III, 1701. Colour woodblock print.

Usually such offers, given generously in the atmosphere of a grand exhibition opening, come to nothing. But true to the professor’s word, the weighty 648-page volume turned up at my home a few weeks later. What a treasure it proved to be, particularly the opening chapters, which emphasize the philosophy of Chinese painting more than its practice. I would like to share some of these little jewels with you, for they cast much light on timeless principles that can be equally applied to icon painting.

The Manual was commissioned by the essayist and playwright Li Yü, whose house and bookshop was called the Mustard Seed Garden, whence the Manual’s name. The texts were compiled and images prepared between 1679 and 1701 by the three brothers Wang Kai, Wang Shih and Wang Nieh. It has long been considered a classic. It draws in fact on earlier writings, and thus represents a long history of accumulated wisdom, like the icon tradition.

The following is a selection of passages from the Manual which have meant a lot to me over the years, followed by my own commentary.

To be without method is deplorable, but to depend entirely on method is worse. (page 17).

The dominant weakness of icon painting in the West is the lack of method, the lack of skill. We have no long-term icon schools, and our art schools rarely train people in the traditional skills of drawing to any depth. Inevitably, therefore, a DIY approach dominates. By contrast, icons in traditionally Orthodox countries often suffer from the opposite problem: too much dependence on skillful copying. Accurate and analytical coping of masterpieces is certainly an excellent way to learn iconography, but should remain a means to an end. To equate Tradition with copying is a return to the Law and to depart from Grace. It betrays a spirit of fear rather than humility.

You must learn first to observe the rules faithfully; afterwards, modify them according to your intelligence and capacity. The end of all method is to seem to have no method. (17)

When we learn a second language, we consciously study its rules of grammar and learn its norms. But as we gain knowledge and confidence, we find our own voice. Iconography should be the same.

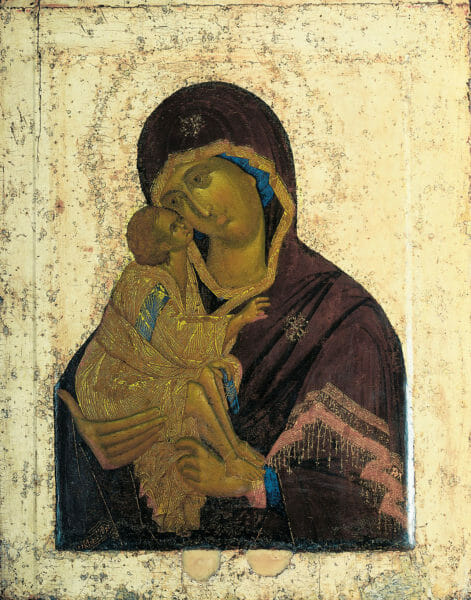

I have heard it said by some Orthodox thinkers that iconography is not art. I disagree. The icon is indeed more than art because it is part of the liturgy and exists for more than aesthetic delectation. But it is at least art. Although the icon’s sacred purpose means that its aesthetic categories are more extensive than those of secular art, it should nonetheless include them. The same universal colour theories and composition principles apply.

Like every human person, God created the icon painter as a living, intelligent, creative being and not as a machine. The aim of the icon painter should therefore be to absorb and live the tradition so much that it passes from being a consciously held second language to being a natural and first language. We can honestly then say that we paint this way because we see this way.

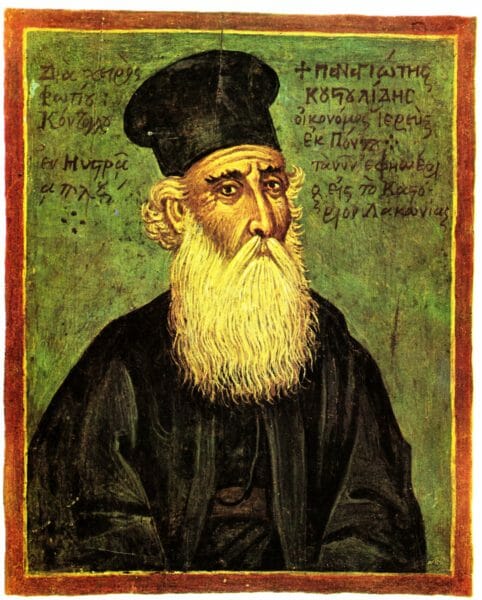

You may disagree, but I find Photius Kontoglou’s portraits more authentically iconographic than his icons. When painting a portrait he does not think: ‘I am painting an icon, so I must make it look like an icon’. Instead, because he is painting a portrait and not an icon he feels free to depict the person how he experiences them, while at the same time, because he lives the life of the Church, Mr. Kontoglou naturally ends up painting his sitter in an iconographic way. This is why, to me at least, they seem more integrated and authentic than many of his icons.

Originality should not disregard the “li” (the principle or essence) of things. (20)

This sentence hints at the heart of authentic originality. An artwork is authentically original not because of its apparent novelty but because it has touched the mysterious core – or as Church Fathers call it, the logos – of the subject.

Orchids, from volume one of an early or perhaps first edition. The sinewy leaf strokes capture perfectly the essence of the orchid flower.

Because this li or logos is spoken by the divine Logos it has a divine quality and therefore also an infinite quality. No one artist can therefore exhaustively express its mystery, hence the newness of authentic originality. Equally, because these different expressions originate in a common logos/li they are in community. The isolation and shallowness of novelty is absent. So, contrary to popular conceptions, there is scope for originality within the icon tradition, as long as it does not disregard the li of its sacred subject . This li will actually generate the originality.

Neither complexity in itself nor simplicity is enough. (17)

I think the author’s meaning here is that what ultimately matters is whether or not the painting captures the li or essence, of its subject. A skilled and inspired painter can use either simplicity or complexity to express this li. These are tools, and not the purpose of the painting. The Rumanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi affirmed this truth when he said: ‘Reality lies in the essence of things and not their external forms. Hence, it is impossible for anyone to produce anything real by imitating the external form of an object.’

… At a later stage, therefore, one may choose either to proceed methodically or to paint seemingly without method. First, however, you must work hard. (18)

Icons are deceptively simple. At first encounter their form can appear to be simplistic, even naïve. But this is illusory. An iconographer can only abstract the subject to its essentials if he or she first understands the complexity of the subject being simplified. As Brancusi once said, ‘Simplicity is complexity resolved’. Complexity resolved, not ignored.

Icons depict the world transfigured, which is very different from the world dematerialized. The Apostle Paul inferred this when he wrote: ‘The material first and then the spiritual’ (I Cor.15:46). The iconographer must work hard first to understand the lower order of the material world before venturing to show it transfigured. In the following page of the Manual the author expands on what he means:

If you aim to dispense with method, learn method. If you aim at facility, work hard. If you aim for simplicity, master complexity. (19)

Hard work is the only path to the authentic abstraction. In the years that I have taught iconography I have found that drapery is the most common stumbling block for learners. Prolonged and analytical study is required to understand the drapery that the icon tradition abstracts. Drapery’s complexity needs to be mastered in order to make sense of its simplification, otherwise it becomes irrational, not supra-rational. Lines need to be understood as horizons of forms and not strings hanging in space.

Learn from the masters but avoid their faults. (20)

Orthodox are correctly taught to respect Tradition. But Tradition is communicated through people who can also make mistakes. No-one is infallible. The Church acknowledges the greatness of the vast majority of St Gregory of Nyssa’s teachings, for example, but rejects his ideas of apokatastasis – the salvation of all. Even the great icon masters make mistakes, or could at least have done some things better. Or perhaps they created something perfect for their time and place, but this does not mean it is appropriate to reproduce their solution in our own time and place. Realism in the face of Tradition sharpens our humility before it, and does not blunt it.

Possess delicacy of skill with vigour of execution. (20)

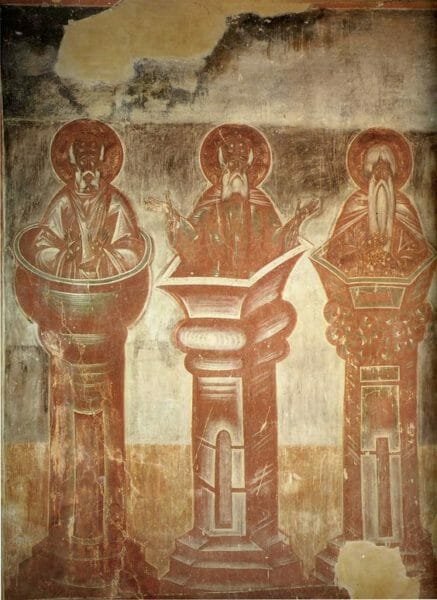

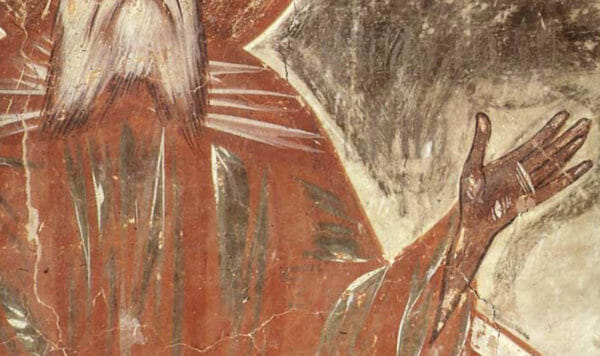

A great exemplar of this principle is Theophan the Greek (c. 1340-c.1410), in particular his frescoes at Holy Transfiguration church on Ilyina Street in Novgorod.

Holy Stylites: Simeon the Elder, Simeon the Younger & Alypius, by Theophanes the Greek, 1378. Transfiguration Church, Novgorod.

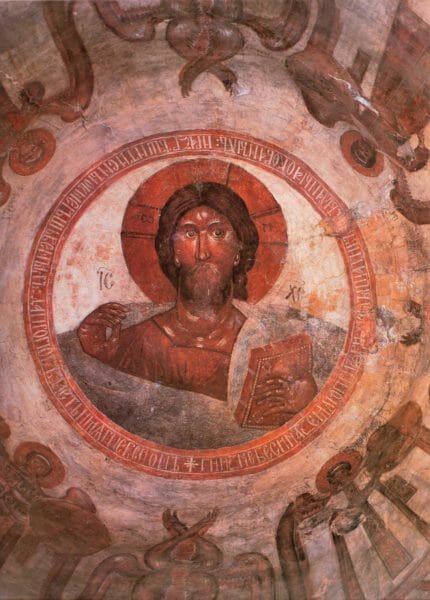

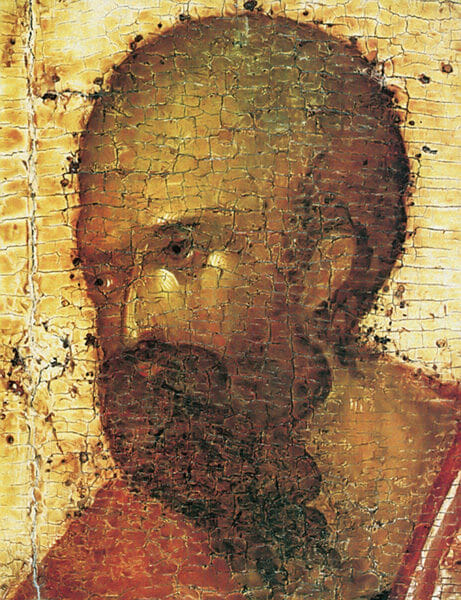

Christ Pantokrator, by Theophanes the Greek (1378). Fresco in the center of the cupola of Spas na Ilyine Church ( The Church of the Transfiguration of Christ) in Novgorod.

These remarkable works are painted, it seems, just with black, red and white pigment, using vigorous calligraphic line and very little modelling. In fact, some contemporaries likened his technique to ‘painting with a broom’. These frescoes were done quickly, and observers say, without copying from models while painting. He painted like a prophet driven to declare the word of the Lord as fast as it came to him.

But despite this vigour, close observation of each brushstroke displays a ‘delicacy of skill’ that could have come only with many years practice.

The miniatures and icons credited to his hand display dexterity and facility of line, but he was not enslaved to this detail when the subject and scale of the Novgorod frescoes demanded a broader hand. His chronicler claimed that Theophan had frescoed more than forty churches – perhaps a symbolic number, but doubtless a lot of churches.

St Paul, detail, by Theophan the Greek. From the deisis tier of the Moscow Cathedral of the Annunciation (1405).

The second fault is described as ‘carving’ (k’o), referring to the laboured movement of the brush caused by hesitation. Heart and hand are not in accord. In drawing, the brush is awkward. (21)

Care and concentration is certainly needed to paint icons well. But so also is a degree of freedom and boldness. As an Athonite monk once told me concerning the Jesus prayer: attention without tension is required. Laboured movement or K’o can happen either through lack of experience, or through a spirit of fear. The former is dealt with by hard work. The latter can be helped by painting non-iconographic works. Since these are not for a liturgical viewer the painter is free to improvise and try things out. They are free to experiment and fail. This hesitancy of line may also have a psychological root, a fearful spirit.

He who is learning to paint must first learn to still his heart, thus to clarify his understanding and increase his wisdom. (26)

For thirteen years I have taught a three-year part-time icon course for The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts. Invariably it is the students who have ‘stilled their hearts’ who are best. This hesychia allows them to observe and analyse while they are painting and thus to correct errors. They concentrate on one step at a time because their minds are not flitting about like a leaf in the wind. This inner quietness allows them to hear the music of heaven in their souls and to harmonize what they paint with this music.

But this inner quiet does not lead only to quiet and comforting iconography. The music of heaven can be intense. The prophet Ezekiel’s and the Apostle John’s visions of heaven are hardly comforting. The frescoes of Theophan the Greek offer an exemplar of a hesychasm that can produce a similarly dynamic iconography. Scholars believe it is highly likely that Theophan the Greek knew of and practiced hesychasm. He was born in Constantinople in the late 1330’s, and was educated there during and after period that hesychasm was such a prominent topic due to the writings and activities of St Gregory Palamas (three church councils on hesychasm were held in the capital in the 1340’s) .

….He should then begin to study the brushstroke technique of one school. He should be sure that he is learning what he set out to learn, and that heart and hand are in accord. After this, he may try miscellaneous brushstrokes of other schools and use them as he pleases. He will then be at the stage when he himself may set up the matrix in the furnace and, as it were, cast in all kinds of brushstrokes, of whatever schools and in whatever proportion he chooses. He himself may become a master and the founder of a school. At this later stage, it is good to forget the classifications and to create one’s own combinations of brushstrokes. At the beginning, however, the various brushstrokes should not be mixed. (26,27)

These are wise words indeed. Because we have so few proper schools of iconography in the West, most beginners tend to go from one five-day course to another, from teacher to teacher. And this tends to be confusing. Or we have the other extreme, where the student exalts one school, their school, as the most spiritual school of icon painting. Find one good teacher if you can, study under them in depth, and after you have mastered their method, explore other schools. Try to find your voice and the approach appropriate to your ministry. Do you work in Africa? Look at African art. Do you work in England? Look at early English iconography. Andrew Gould has tried to apply this principle to church architecture in the USA, and the same can be done in iconography.

Literary and intellectual training greatly aid the use and control of the brush, adding to its power. (30)

If one aims to avoid the banal, there is no other way but to study more assiduously both books and scrolls and so to encourage the spirit (ch’I) to rise, for when the vulgar and commonplace dominate, the ch’I subsides. The beginner should be hopeful and careful to encourage the ch’I to arise. (34)

To be an iconographer is not just to be a craftsperson. A myriad of decisions is made in the process of designing and painting, and these should be informed by deep theological, artistic, historical and aesthetic knowledge. But apart from such practical use of knowledge, as the Manual suggests, it also enriches the painter as a person, raises their ch’I or spirit. Theophan the Greek is a great example of the philosopher painter. He studied both art and philosophy in Constantinople, and indeed was revered in Russia as a philosopher as well as a great iconographer. Crowds would gather to watch him paint, and he would even discourse with them on exalted topics while painting.

What better way to end this little meditation than a passage from a letter by a friend of Theophan the Greek, the chronicler Epiphanius the Wise, which from first-hand experience describes the master at work:

When he was drawing or painting, nobody saw him looking at existing examples, as would do some of our icon painters. He, on the contrary, appeared to paint his frescoes with his hands while walking back and forth, talking to visitors, considering inwardly what was lofty and wise and seeing the inner goodness with the eyes of his inner feelings.

Notes:

Thank you ! Beautiful and helpful reflections. Makes me want to explore Chinese brush painting as well as to grow in iconography.

Thank you, Gary. Although the Chinese hold their brush rather differently than most iconographers (that is, vertically), the spirit of concentration and freedom required for their calligraphy must surely help the iconographer. Good luck!

Articulating the proper relationships between tradition and originality, study and mastery, cannon and innovation, was one of the principal reasons for starting the Orthodox Arts Journal. It’s pleasing to see these relationships expressed so beautifully in Chinese tradition. And I think it’s very valuable for us Orthodox artists to be reminded that our struggles are not different from those of other artists. Artistic tradition – both maintaining and transcending it – is a universal quality of human civilization, not a unique circumstance of the Orthodox Church.

Orthodox iconography has its own stylistic qualities and its own liturgical purpose, but it is still art like any other – the fruit of hard work, humility, and courage.

This search really gives sense to true iconographers being true hagiographers. I appreciate especially the comment, ‘simplicity is complexity resolved.’ Another minor point of interest was the difference in holding the brush, as though not a tool in the hand but an extension or limb of the hand, a part of the body. Thirdly, this idea of revealing the logos of the human being through line and color is discussed in more detail as a principle beginning within Byzantine Iconography, according to George Kordis. See his book, Icon As Communion, published by Holy Cross Press, Brookline, Massachusetts.

[…] Hart delves into the curious world of orthodox iconography: “Icons are deceptively simple. At first encounter […]

[…] By AIDAN HART and originally posted here. […]