Similar Posts

Editor’s Note: This essay was originally written in Russian by master iconographer Anton Daineko of Minsk, Belarus. It beautifully explores the paradox of creativity within iconography from the very personal perspective of a lifelong practitioner.

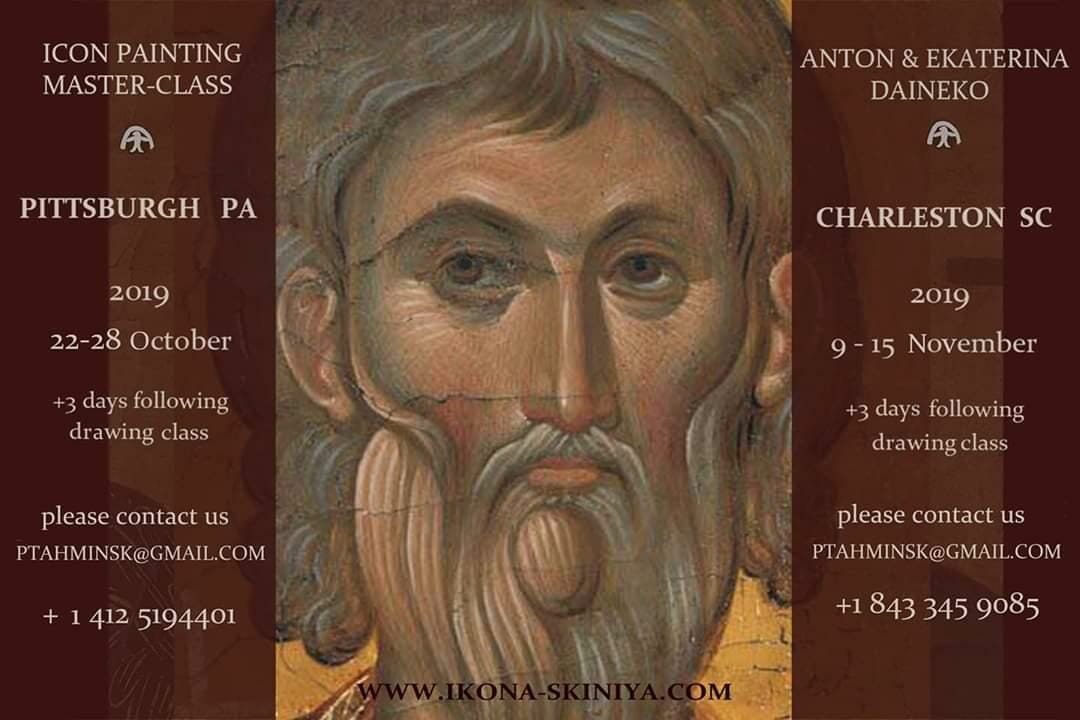

Anton and Ekaterina Daineko regularly teach icon-painting workshops in the USA, which are highly recommended. They have upcoming workshops in October and November of this year, for which space is still available. See their website here.

Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God – Matthew 16:16

An iconographer once noted, “My online friends fall into two categories: artists and iconographers. The artists share photos of their paintings, constantly heaping praise on each other’s work. The iconographers, on the other hand, constantly argue with each other.” This is a very astute observation. Indeed, heated debates, regularly arising on various websites and forums frequented by iconographers, have become the trademark of such internet venues. Disagreements mostly flare up over contemporary iconography’s path of development, that is, whether the icon should be MODERN or must stay TRADITIONAL, whether copying of icons should be avoided or encouraged, whether creativity should be part of icon painting at all.

As a child, my favorite book was The Wizard of Oz. There, throughout the story, two principal characters – the Scarecrow and the Tin Man – are engaged in an endless discussion as to which is the more important for a person: the heart or the brain. They jump into this argument at every opportunity even as their respective actions demonstrably prove the necessity of both the brain and the heart.

Something along these lines is happening now in the field of iconography. The answers to the above questions are obvious. Should the icon be traditional? Of course it should be. To eschew tradition can yield images of the Saviour as an American Indian or the Mother of God with a soccer ball, to give but two examples.

Should the icon be modern? Undoubtedly. Corresponding to each significant time period of the past was a specific iconographic style and also a unique view of the icon. Such is only natural and cannot be otherwise, which is why an icon transplanted from a different era often looks like an imitation.

In my opinion, the question runs much deeper. It would be somewhat superficial to declare that an icon MUST be this or MUST NOT be that; it would be very hard indeed to say what an icon MUST really be. It is more practicable to look into what an icon actually IS.

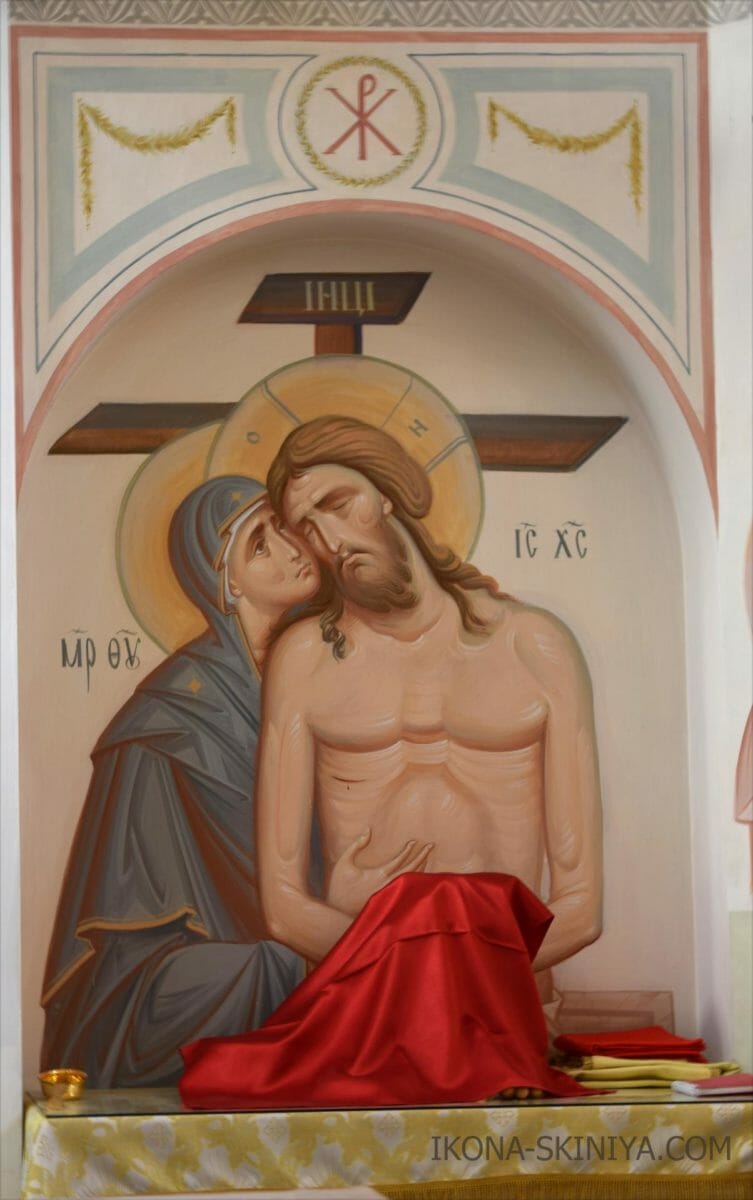

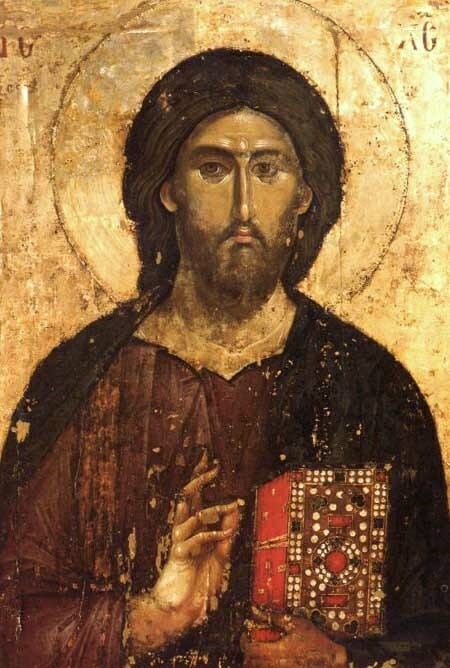

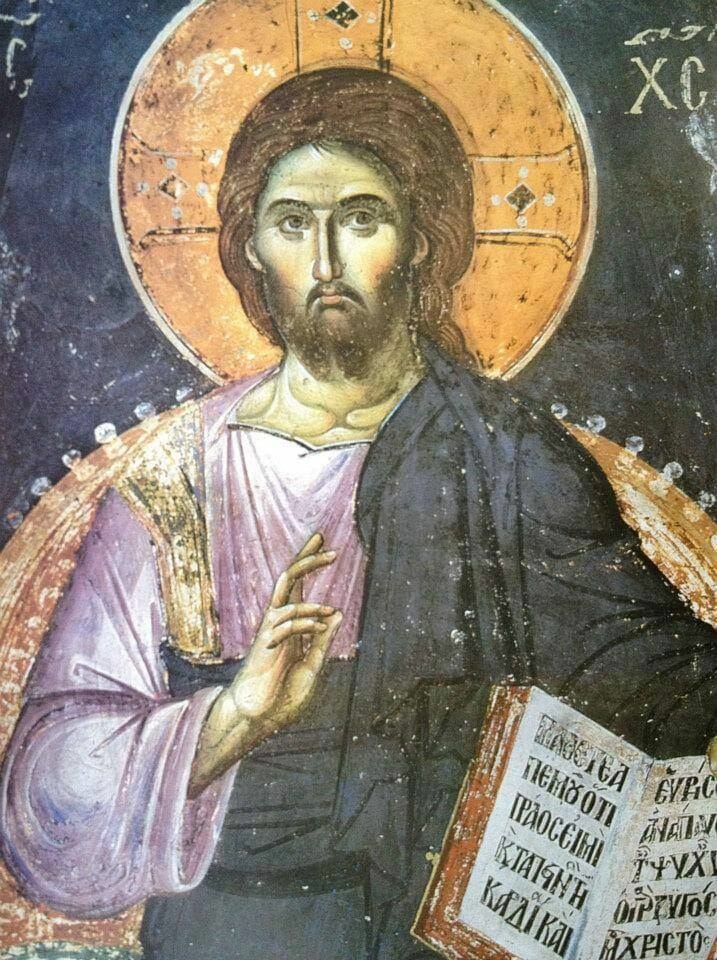

Several years ago, a priest from Grodno came to order icons for the iconostasis from us. He generally gave iconographers a wide berth of artistic freedom, with just one stipulation: he wanted his icons painted “Rublev Style”. Such a preference is well known to iconographers. The phrase “Rublev Style” is a sort of magic buzzword uttered by many clients. With the Grodno priest, we agreed that I would pick several icons as models to guide me during my work. I then made the selection which included the 13th-century Hilandar Icon of the Saviour, the Byzantine fresco of the Saviour by Manuel Panselinos, the Icon of the Saviour from Vatopedi Monastery, and a few other photos of works which, like the ones I just mentioned, had nothing to do with Andrei Rublev but were highly expressive in terms of beauty and artistic vision. During my next meeting with the priest, I laid out the samples in front of him, and he replied with complete satisfaction “Yes! This is exactly what I had in mind”.

This episode demonstrates the unshatterable link between traditional and modern.

These sample icons were painted at different times and in different manners; the faces are also notably different from one another. In fact, observing the icons in comparison, the differences become even more pronounced. Nevertheless, a glance at any of these icons leaves us in no doubt as to Whom we see in front of us: the Lord Jesus Christ; nor do we get any feeling that something may be out of place.

To the contrary, each of these images makes an enormously powerful impact on any viewer. The verdict on these icons is practically unanimous – iconographers and art historians, painters and priests, critics and everyday folks all agree that they are looking at masterpieces of Christian art, from both the artistic and the spiritual perspectives. Though different iconographers, from different periods, painting in different styles, they have each produced undisputedly beautiful images of Jesus: one but many; unique but the same; contemporary in their day; traditional in the Church.

Hence the conclusion: despite the apparent differences, all these images (unquestionably representing the summit of icon painting) have something – a certain quality – in common which gives the viewers an unerring conviction they are in the presence of a GENUINE icon.

That, in turn, allows us to talk about the existence of a particular criterion applicable to an icon’s authenticity, however difficult and elusive it may be to define. But my example with the selection of iconographic masterpieces for the Grodno priest suggests that such a criterion could be, in fact, at least partially concretizable. If it applies to the masterpieces mentioned, it may be relevant to other icons as well. This is the critical question: What exactly constitutes that certain quality?

The Criterion

Commenting on copying in iconography, Father Igor, a priest from Minsk and himself an icon painter, noted that “There are no icon copies; each icon is a REVELATION”. Naturally, this raises questions: is it even possible to define such a delicate matter as REVELATION, and what aspects should be included under the resultant definition?

It cannot be answered in a few simple words. With some icons, everything is easy: one look at the Redeemer from the Zvenigorod deesis tier, and you feel that it really is a REVELATION. But with most icons, the matter is far more complicated.

Icon of Christ from the deesis tier of an iconostasis, discovered in Zvenigorod, Russia. 15th century.

It would be appropriate here to recall the words in the epigraph to this article, the Apostle Peter’s reply to Our Lord’s question “Who do you say that I Am?” – “YOU ARE THE CHRIST, THE SON OF THE LIVING GOD“.

Perhaps this line holds the key to understanding much about the Church, including the canonical texts: in those texts, the early Christians saw an image of the LIVING GOD, crucified and raised from the dead. And that is what is most precious in the Church. It is precisely the PRESENCE of the Living God that sets the Christian Church apart from other religions and other communities. And it is precisely this PRESENCE that we can observe in scripture as well as virtually everything else in church life. The icon is no exception in this regard.

The iconic image consists of many simple elements: strokes, stripes, and smudges, while the different colors are obtained by various combinations of minerals and egg yolk. Taken separately, none of these elements carry any artistic – let alone spiritual – meaning in and of themselves. But when these elements come together in a particular combination, a miracle occurs: the strokes, the stripes, and the smudges cease to exist, and we see the Face of the Living God looking directly at us. It is as much of a miracle as the image of the Living God emanating from the simple words of the Gospels’ narrative.

It is this task – the amalgamation of a multitude of disparate visual elements into an Image of the Living God – that could be defined as the main purpose of icon painting.

How this can be achieved, if at all? – Certainly not by means of technique or methodology. Style is of relatively little consequence, for the history of Christian art offers many examples diverging in stylistic or technical aspects. The level of technical mastery definitely matters, yet its role is by no means decisive. There are many examples of icons impeccably painted from a technical perspective but with no life to them. And, on the contrary, there are plenty of aesthetically imperfect depictions which nonetheless possess an invaluable quality.

Once again we arrive at a conclusion that a criterion is very hard to define. Ultimately it depends on personal perception—but that perception, as we will see, is rooted not in subjective reality, as much as it is in the revelation of God to the heart. As can be seen from the earlier example with the selection of the best iconographic models, this does work. People, whether they are ‘near’ the icon or ‘far’ from it, can see and feel in various iconographic images the presence of OBJECTIVE TRUTH to a lesser or greater extent.

The task of the icon painter is to convey this objective truth, but they can only do so by means of their own subjective perception. It would therefore be quite interesting to explore what that personal (subjective) approach to the icon is.

The Iconographer

Several years ago, I designed something like an algorithm of icon creation. It was based on my own work experience, but as it turned out, practically all the iconographers of my acquaintance followed a similar algorithm. The process is divided into four stages, with each one sequentially leading into the next.

Stage 1 is called “Brilliant!” and covers the run-up to a new project. You are full of energy and creative ambition. It seems you have AT LONG LAST acquired a clear understanding of WHAT to paint and HOW; all the troubles that had come before were merely an uncertain phase, but from now on, things will be very different. Yes, you are ready to move mountains.

Stage 2 follows Stage 1 and is called “What a nightmare!” Right in the middle of the work, you suddenly realize with horror that not only have you failed to implement even a small fraction of your ambitious plans, but for some reason, you have difficulty mustering the skills that were so natural and readily available in the past.

Which leads directly into Stage 3 known as “Lord have mercy” – an appeal to He who has the true power to create the icon.

Everything usually comes to an end at Stage 4, or “Thank God!”: the work finally is done, and even if it fell short of the original expectations, it is at least no worse than your “usual”.

Afterwards, there follows an interim stage during which you gradually claim ownership of what had never really been yours to begin with, arriving at “Transfigured!”

The icon painter must maneuver through a whole array of paradoxes throughout the creative process. The most important of those is how, and to what degree, one reconciles the personal approach with the Divine action. The determination of that degree is very much up to the painter.

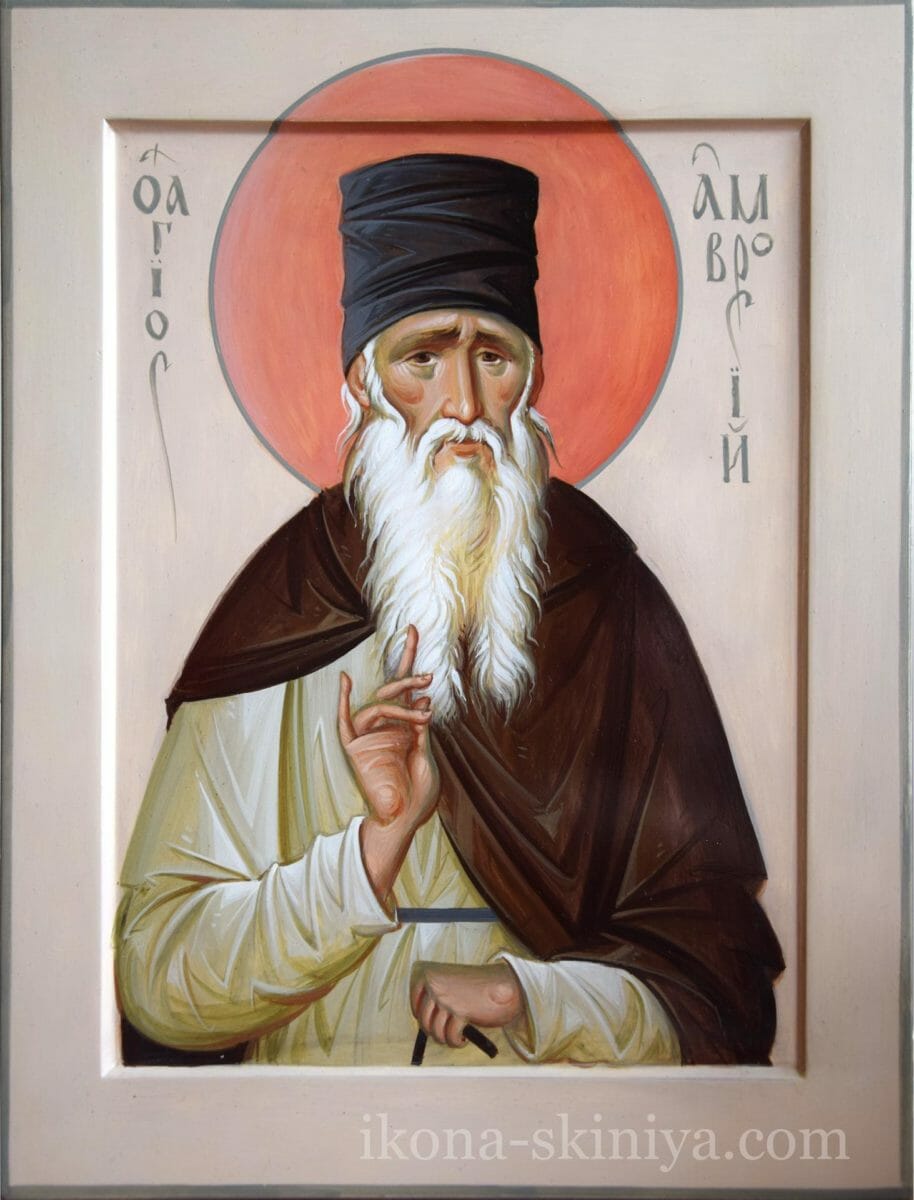

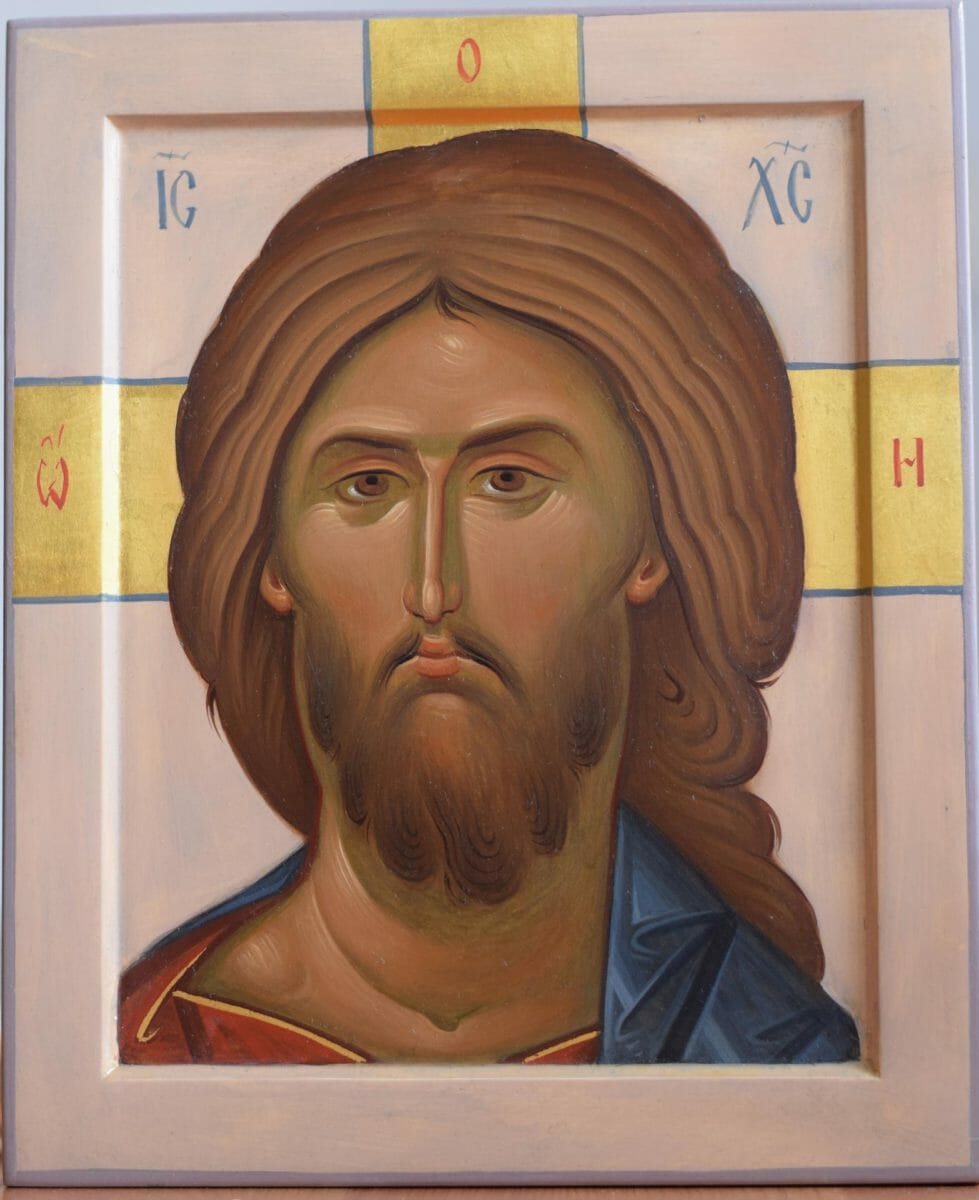

Icon painted for the iconostasis of St. John of the Ladder Orthodox Church, Greenville, SC, by Anton and Ekaterina Daineko

Paradoxes accompany every Christian from the get-go. There is even a catchphrase for that: “The Gospel is woven from paradox”. Christianity is freedom in servanthood. The New Testament is not a rule book but rather a KEY to understanding of how to act in a particular situation. Freedom is a mysterious paradox: “do not use your freedom to indulge the sinful nature” (Galatians 5). First must be last; master must be servant, greatest must be least.

The most profound of Christian thinkers were forced to grapple with and formulate the greatest and deepest of these types of paradoxes. For example, how does one unify two seemingly incompatible things—the natures Divine and human?

It would not be an exaggeration to say that a Christian’s entire life is grounded in such paradox. And more often than not, this delicate balancing act between two poles strangely enough turns out to be the only possible way forward. With regards to the paradoxes facing an icon painter, Archbishop Zenon once said, “the iconographer must kill the artist in himself”.

The question could also be put as follows: is it desirable to fight individuality, and should its destruction be viewed as an accomplishment?

An answer can be found in the remarkable variety of iconic depictions created over the past centuries. What else accounts for this treasury of riches if not artistic individuality? And the demonstration of such individuality did not preclude the creation of masterpieces; some mentioned above whose merits are obvious. That the absence of individuality is no virtue can be quickly ascertained upon examining the vast quantity of ‘iconographic products’ churned out by numerous factories and ‘co-ops’ today—places where assembly-line mass production of icons surely robs them of any distinctiveness without offering much in return.

All this presents an opportunity to see the individuality of an artist as an integral factor in icon painting. The spiritual battle is for the artist to prevent his individuality from being an end in itself—from pointing to himself, rather than to Christ. His individuality is a gift from God, allowing him to point, in his own way, by his artistic expression, to the one true man, Jesus Christ. When the iconographer’s individuality shines more through the icon than the Light of Christ, it distorts the very purpose of icon painting.

Any icon has two components: the Divine and the human. The Divine component remains the same over millennia, while the human component has forever been in a state of flux depending on the time, place, societal aesthetic conventions, or the perspective of a particular artist.

How is it possible to balance the content of the icon and the artistic individuality of the iconographer? That such a balance can indeed be within reach is suggested by the examples of the icons mentioned above. Of course, it is difficult to achieve the same perfection that those few exceptional authors were able to. What success is attainable for us can only be determined through practical experimentation.

We have seen in other examples that so much in the life of a Christian involves finding an apparently fragile balance, and this, too, can serve as a confirmation of our journey.

One further important aspect that deserves mention is personal experience, especially of a spiritual nature.

Again, a parallel with theology would be highly appropriate. Profound theological deliberations cannot be imagined without a solid personal experience of the One True God, and neither can a profound icon. The word said about God will only be a living word if it is uttered from the depths of inner experience tied firmly to the self-revelation of God. So too with a painted icon. Both the theological deliberation and the iconic image can be likened to the small tip of an iceberg whose main body is hidden under water.

The chronology of an iconographer’s spiritual progress can largely be traced through the chronology of his works. In my humble view, the iconographer, throughout his whole creative life, strives to depict just ONE image of Christ – or Mother of God, for that matter – trudging toward them along a thorny path overgrown with different styles, techniques, and artistic perspectives. And each new icon is yet another stroke added to this one image which the iconographer had been trying to grasp from the very beginning but which has always been elusive. With the passage of time and the painting of many icons, the image becomes increasingly clear and distinct. This quest has a noble goal: to depict God as He really is, to cleanse His image as much as possible from all distortions and impurities of artistic style, momentary personal preferences, and other chance details.

This quest explains both a large number of similar images by a particular iconographer and, vice versa, a noticeable variety in depictions. In the first case, it is likely a conscious phase in artistic development: that the painter is not eager to plunge into extremes and stylistic excesses is a plus. In the second case, it is the result of intense and daring exploration.

Mystery solved in Mystery: the Icon is Born in Paradox

It turns out that only in this balancing act can the icon be born. The icon is traditional and modern; it is individual and free of individuality, a product of communal artistic pursuit and, at the same time, the deeply personal attitude of the iconographer. The icon inhabits the boundary of these two worlds and carries the features of both.

There seems to be no other way. Throughout the entire history of Christian thought, no single one theologian – no matter how great – has been able to explicate Christ in His entirety. The image of Jesus made into words by theologians became possible thanks to continuous labors of many dedicated people over a huge period of time. Without the contribution by one, there would be no achievement by another, as each new thinker was building upon the foundation left by his predecessors and adding something that had yet to be unearthed.

We see the same with icon painting. If here on Earth the transmission of the Divine Truth is possible only with the synergy of men and women, each possessing their own unique individuality, their unique combination of talents, as well as their unique limitations, then perhaps all iconography can likewise be viewed as a continuous endeavor to visualize and depict the One, True God as fully and accurately as possible. Each new icon and each new image is yet another word, yet another tiny stroke adding to this portrait. And the loss of such a stroke causes damage – barely noticeable, but damage nonetheless – to the common depiction.

This common depiction could perhaps be considered the LIVING ICON of our God and Savior. And the process of creation of this Icon therefore continues…

This is a wonderfully written essay. As a student iconographer, I can relate to Anton’s description of the stages of emotional response to one’s efforts during the process of icon painting.