Similar Posts

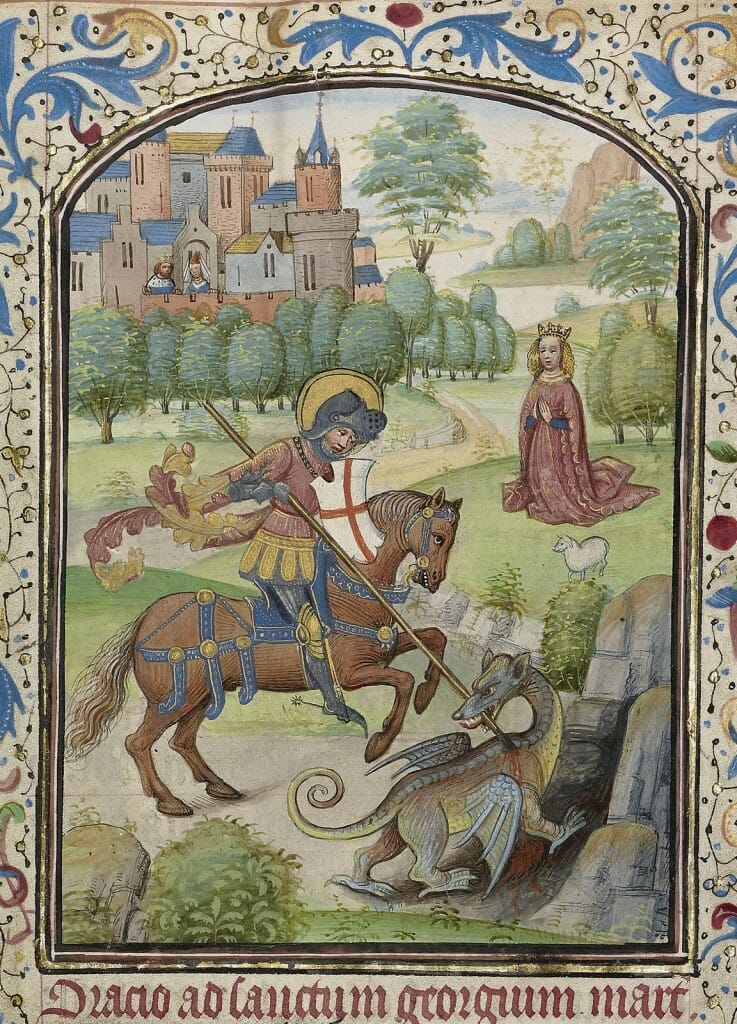

St. George and the “legendary” dragon.

In the comment section of my last post, a reader suggested that what the world needs nowadays is not more Lives of Saints, but more living examples of sanctity. “No one reads the Lives,” he said. Perhaps he is right. A living, breathing saint should be a far more convincing inspiration than the (sometimes) idiosyncratic retellings of the lives of long-dead saints. But if that were the case, what are we to make of the following story?

The newly-canonized Elder Paisios, upon hearing of a certain Elder Joseph the Hesychast, decided to visit him. Immediately, several other monastics tried to dissuade him. They recounted horror stories of how Elder Joseph beat his monks, how he practiced self-flagellation. Then they topped it off with the magic words: Elder Joseph is possessed and deluded. Elder Paisios decided not to visit his fellow-saint, and later regretted it as one of the great mistakes of his life.

If a holy man was not able to recognize sanctity when he heard about it, what is to prevent us from walking right past the world’s greatest saint, even if he lives next door? I believe that is exactly why we need the Lives of the Saints more than ever, if only because they, being written by poets (or at least those with poetic souls), help nurture a poetic way of viewing the world as an antidote to the mindset of the scientific method (see my previous posts here and here).

Newly-canonized St. Porphyrios reminds us of the importance of this poetic way of experiencing the world:

For a person to become a Christian he must have a poetic soul. He must become a poet. Christ does not wish insensitive souls in His company. A Christian, albeit only when he loves, is a poet and lives amid poetry. Poetic hearts embrace love and sense it deeply. (Wounded by Love, p 218)

“But,” says the skeptic, “what about all those legendary elements in the lives, all those historical inaccuracies, all those repeated motifs? They are nothing more than fairy tales! Are these really necessary for the development of this poetic sense?” Just for the sake of argument, let us assume that the Lives really are “littered” with pagan myths, legendary events, and even fairy tale elements. Does that mean they should be disregarded? J.R.R. Tolkien has something to say about that:

When we have examined many of the elements commonly found embedded in fairy-stories … as relics of ancient customs once practiced in daily life…there remains still a point too often forgotten: that is the effect produced now by these old things in the stories as they are…They open a door on Other Time, and if we pass through, though only for a moment, we stand outside our own time, outside Time itself, maybe. (“On Fairy Stories”)

What Tolkien says about tropes in fairy tales is just as true about legendary events or repeated motifs in the Lives, such as the miraculous appearances of icons on rivers, ascetics as infants fasting from their mother’s milk on Wednesdays and Fridays, angels imparting miraculous gifts of learning to the illiterate child. Even if, for the sake of argument, we concede that they could never happen in “real life” (whatever that is), they have a “literary effect” that helps make the Lives extremely effective instruction manuals for us who are mere children in the faith.

Tolkien’s essay “On Fairy Stories” is an unexpected treasure-trove of wisdom regarding the usefulness of “fantastical elements” in the Lives of the Saints. True, he speaks of fairy tales, not hagiography. But I am still assuming, for the sake of argument, that the Lives of Saints, as they have been handed down to us, are full of fairy tales. In this light, his essay is very illuminating. First of all, Tolkien argues for the usefulness and necessity of fantasy in and of itself:

Fantasy…is, I think, not a lower but a higher form of Art, indeed the most nearly pure form, and so (when achieved) the most potent. Fantasy, of course, starts out with an advantage: arresting strangeness. But that advantage has been turned against it, and has contributed to its disrepute. Many people dislike being “arrested.” They dislike any meddling with the Primary World, or such small glimpses of it as are familiar to them. They, therefore, stupidly and even maliciously confound Fantasy with Dreaming, in which there is no Art; and with mental disorders, in which there is not even control: with delusion and hallucination.

This is the response of those who would prefer to see nothing but straight biography in the Lives of the Saints. To such lovers of Reason, Tolkien retorts:

Fantasy is a natural human activity. It certainly does not destroy or even insult Reason; and it does not either blunt the appetite for, or obscure the perception of, scientific verity. On the contrary. The keener and the clearer is the reason, the better fantasy will it make. If men were ever in a state in which they did not want to know or could not perceive truth (facts or evidence), then Fantasy would languish until they were cured. If they ever get into that state (it would not seem at all impossible), Fantasy will perish, and become Morbid Delusion. For creative Fantasy is founded upon the hard recognition that things are so in the world as it appears under the sun; on a recognition of fact, but not a slavery to it.

Far from denying “facts,” fairy tales do a great deal more to illuminate the way the world is than dry scientific reasoning every could. There is a reason for this. Fantasy helps us see truths we have stopped seeing, because we have become so used to them that we no longer consider them at all:

We need, in any case, to clean our windows; so that the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of triteness or familiarity… This triteness is really the penalty of “appropriation”: the things that are trite, or (in a bad sense) familiar, are the things that we have appropriated, legally or mentally. We say we know them. They have become like the things which once attracted us by their glitter, or their colour, or their shape, and we laid hands on them, and then locked them in our hoard, acquired them, and acquiring ceased to look at them.

But there is an even more important function that fairy tales fulfill. They are all either presentiments or echoes of the “greatest story every told,” the Gospel:

I would venture to say that approaching the Christian Story from this direction, it has long been my feeling (a joyous feeling) that God redeemed the corrupt making-creatures, men, in a way fitting to this aspect, as to others, of their strange nature. The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories… But this story has entered History and the primary world…The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation… There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true, and none which so many skeptical men have accepted as true on its own merits. For the Art of it has the supremely convincing tone of Primary Art, that is, of Creation. To reject it leads either to sadness or to wrath. It is not difficult to imagine the peculiar excitement and joy that one would feel, if any specially beautiful fairy-story were found to be “primarily” true, its narrative to be history, without thereby necessarily losing the mythical or allegorical significance that it had possessed. It is not difficult, for one is not called upon to try and conceive anything of a quality unknown. The joy would have exactly the same quality, if not the same degree, as the joy which the “turn” in a fairy-story gives: such joy has the very taste of primary truth. (Otherwise its name would not be joy.) It looks forward (or backward: the direction in this regard is unimportant) to the Great Eucatastrophe. The Christian joy, the Gloria, is of the same kind; but it is preeminently (infinitely, if our capacity were not finite) high and joyous. But this story is supreme; and it is true. Art has been verified. God is the Lord, of angels, and of men—and of elves. Legend and History have met and fused.

It is an astounding and brave thing that Tolkien claims. “Even so,” says the skeptic, “does not the fulfillment of all myths in the Incarnation make all further myths and legends obsolete? We no longer need fairy tales, since Christ has come down in the flesh!” Ah, but Tolkien has an answer to that as well:

But in God’s kingdom the presence of the greatest does not depress the small. Redeemed Man is still man. Story, fantasy, still go on, and should go on. The Evangelium has not abrogated legends; it has hallowed them, especially the “happy ending.” The Christian has still to work, with mind as well as body, to suffer, hope, and die; but he may now perceive that all his bents and faculties have a purpose, which can be redeemed. So great is the bounty with which he has been treated that he may now, perhaps, fairly dare to guess that in Fantasy he may actually assist in the effoliation and multiple enrichment of creation. All tales may come true; and yet, at the last, redeemed, they may be as like and as unlike the forms that we give them as Man, finally redeemed, will be like and unlike the fallen that we know.

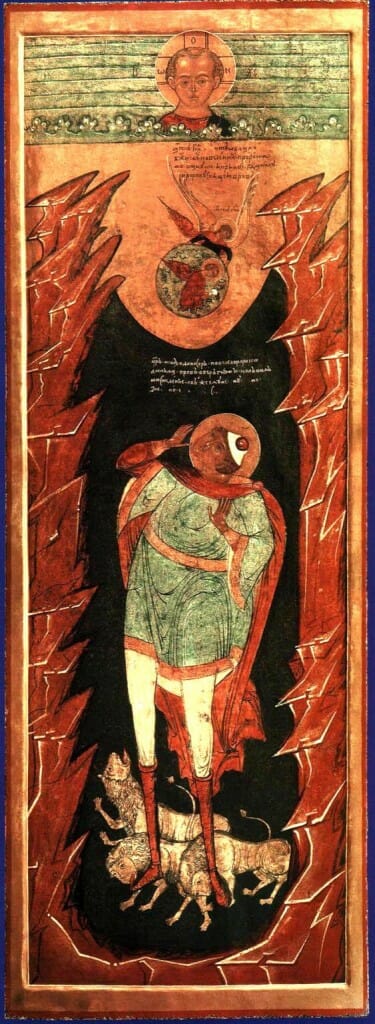

So we should welcome these fairy tale elements, even in the Lives of the Saints. The Lives are not made poorer by the inclusion of pre-Christian heroic exploits, slaying of dragons, expulsion of snakes from the bellies of pagans, miraculous journeys over impossible distances. They are enriched, as are we, if we train ourselves to have a moral imagination, not a diabolical one, if we strive to develop a poetic soul, not a critical one that destroys all it touches.

For the record, I am not suggesting that critical hagiography is a completely useless pursuit. It only becomes dangerous when we stop seeing the world as a constant revelation of God’s miraculous love. The Lives of the Saints, in the form they were preserved by the Tradition of the Church, help us regain that vision of a world fallen, but still illumined by grace.

Very interesting idea here – something I had always intuitively felt, but never expressed. It is related to an architectural matter I recently spoke of in my talk at the Climacus Conference: the perpetually ‘exotic’ quality of Orthodox architecture. There seems to have always been a tendency for Orthodox churches to be a bit fantastical – from 6th-century Byzantine architecture, which takes Roman forms but ornaments them in architectural carving derived from Persia, to 16th-century Russian churches, which are adorned with exotic and orientalist features like onion cupolas. I suggested in my talk that a certain amount of fantasy is iconic in liturgical art, because it shows us that the Church is not of this world – churches are different from our routine buildings. I feel similarly about the fantastical elements of hagiography – they show, poetically, that the saints lived in the Kingdom of God, outside of this world with its mundane rules, even whilst they were alive.

In a similar manner, Hilaire Belloc wrote in a collection of essays of his “First and Last” concerning the legends of St. Patrick:

There was once–twenty or thirty years ago–a whole school

of dunderheads who wondered whether St. Patrick ever existed, because

the mass of legends surrounding his name troubled them. How on earth

(one wonders) do such scholars consider their fellow-beings! Have they

ever seen a crowd cheering a popular hero, or noticed the expression

upon men’s faces when they spoke of some friend of striking power

recently dead? A great growth of legends around a man is the very best

proof you could have not only of his existence but of the fact that he

was an origin and a beginning, and that things sprang from his will or

his vision.

Ah, Belloc! “Dunderheads,” indeed. You can always expect him to speak his mind.

I’ve always loved Tolkien’s essay On Fairy Stories, but I never thought about its ideas in connection with hagiography. When I first moved into Orthodoxy (from a Protestant background), appreciating the more mythic qualities of saints’ lives was difficult for me. I wish I’d had your article then! Thanks for a great article!

Thanks, Katherine, that’s gratifying to hear. It surprises me how many layers one can uncover in Tolkien’s writings. Truly a profound man.

Thank you for writing this, Nicholas. It reminds me of some underlying reasons why I love reading fiction so much.

I believe Tolkien’s quotations apply to fictional fairy tales rather than biographies or hagiographies, right? It’s a bit of a stretch for me that you are using his arguments to justify the presence of fantasy in the Lives of the Saints. While part of the same tapestry of Holy Tradition, the Lives haven’t been vetted like Holy Scripture has. Nor were they produced by the same culture – the Jews were much better at memorizing and passing on oral tradition than gentile culture has ever been (with possible exception of you Waldorfians out there).

There is this principle that we shouldn’t lie to our children. Like, if you teach your kids to believe in the big red man Santa Claus who comes down the chimney cookie-eating and gift-giving. When they find out it’s not true, then what else were you lying about? Maybe this whole Jesus story is just a nice fairy tale – good literature but not actually worthy of founding my worldview upon. Holding your nose and closing your eyes to elements of Holy Tradition that you actually doubt just makes it that much easier for your kids to dismiss your religious credes as not being any more ‘real’ than their own emotional experiences and the findings of contemporary science.

I think we need to be very open-eyed when relating fantastic stories to our children that the Church’s Tradition has handed down to us. I personally want to be honest with my children about my own doubts. If you try to convince yourself that you believe 100% of it, your kids will smell a rat. Why not be honest with them that you believe 98% of it?

Thank God that this 100 years has seen much better hagiography than the preceding couple centuries. I personally feel that there are a number of Lives written with rose-colored glasses in such a manner that it sets forth not an ‘ideal’ for contemporary Christians to aspire to, but rather an ‘impossible ideal’ that was never quite accurate. My generation has a thirst for grittiness, for vulnerability, for uncertainty. The Church needs to go there. Just saying’

I will say though that I have a much higher tolerance for fantastical elements in visual representations (i.e. icons) than I do in the written word. Maybe I am hypocritical in that, but the world of metaphor and analogy, poetry and fantasy seem more accessible to the visual realm. Maybe it’s because you always know that there is illusion going on in visual art – line and color indicating forms that are arranged to indicate meaning – whereas in the written word we are accustomed to entering a mode of supposing objective ‘facts.’

What do you think?

Thanks for the comment!

I think you answered your own question. On the face of it, I really don’t see why we should have more tolerance for the abstract in visual art, but not in the written word. Maybe it has something to do with this society putting too much stock in what is written as “true.” My first two posts on the Lives deal more with “what is truth,” by the way, but I do think it would be useful for people to wean themselves off from an idea that “if it’s written, it should be true,” especially if “true” means historically accurate. It’s missing the point, frankly. I think the travesty that modern mass media has become only proves that while we would like to think that the written word is “factual,” it actually if far from it. It certain isn’t true all the time.

As for the Scriptures being “vetted,” that’s actually not quite the case. The Scriptures were never vetted. There was the gradual formation of a canon, but it only confirmed the truth of Scriptures as they were revealed. There was no committee deciding what to keep in Scriptures and what not to. That’s not how the Church works. Put very roughly, the truth is the truth because it’s the truth, not because the Church decides it’s the truth. Fr. George Florovsky describes this much better than I ever can in “The Lost Scriptural Mind.” Highly recommended reading.

By the same token, the use of the Lives in the services is about as solid a confirmation of their worth as you can get. The theology of the Orthodox Church is primarily liturgical, let’s not forget. If it’s in the services, it’s been “vetted,” so to speak (sorry, I seem to have contradicted myself 🙂

I agree that recent hagiography is more palatable to the modern ear. However, let’s not become dismissive of the past’s way of dealing with reality, rose colored glasses or not. C.S. Lewis calls it “chronological snobbery, the uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate common to our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that account discredited.” The Church doesn’t do “current and hip,” it does “timeless and traditional.” That’s a good thing!

As for expressing doubts to your children, that’s a pastoral issue. I wouldn’t comment on that except to say that I personally think we need to worry less about our kids “smelling rats” and more about giving them a worldview that allows for mystery and sacrament, without the incorrect notion that everything can be explained rationally, especially when it simply can’t.

Just my thoughts. Thanks again!