Similar Posts

Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” is a term popularized by the opera-composer Richard Wagner to describe the ideal integration of multiple art forms into a single creative vision. Clear to the Orthodox Christian, the Divine Liturgy is the supreme expression of this idea, combining communal prayer, Holy Tradition, and all the arts for the glory of God and the salvation of mankind. A church building, as the vessel of that sacred liturgy, ideally reflects the same integration. In a temple, we should expect to find a harmony of architecture, scultpure, and painting in service of a spiritual and artistic whole.

In contemporary projects, unfortunately, this unity is rather rare. Churches are typically designed, built, and only later decorated by artists working independently. The iconostasis, furnishings, and wall paintings may be added sequentially, without recourse to any standard. The result is often discordant, serving poorly as a witness to the harmony to be found in the Kingdom of Heaven—of which a church (in our tradition) is obliged to be an icon.

Aware of this problem, the team behind the chapel of the St. Onuphrius the Great Foundation [1] in Florești, Romania, collaborated from the outset to address it. Architect Călin Chifăr, sculptor Andrei Răileanu, and painter Andrei Mușat worked in continuous dialogue to affect a unified creative vision.

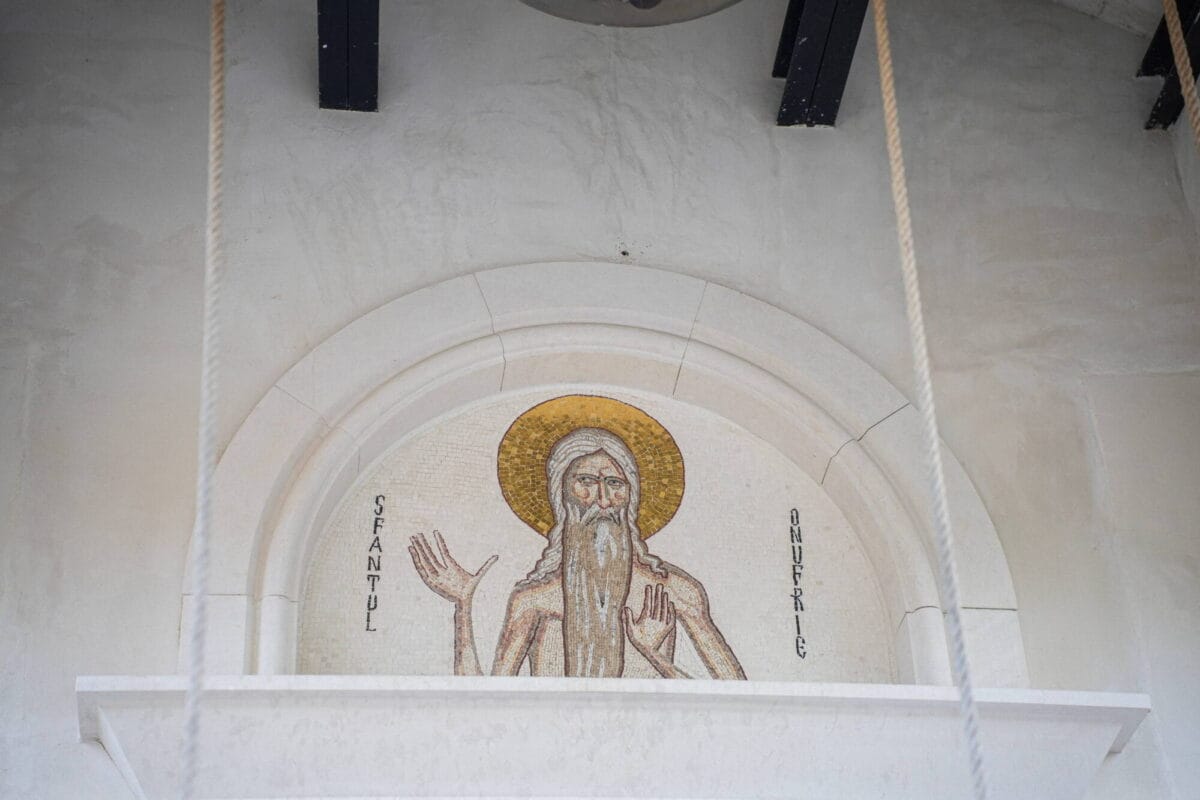

The Foundation to which the chapel belongs provides care for orphans and abandoned children. Its chosen protector, Onuphrius, a 4th-century Persian-born ascetic, is venerated locally as a patron of orphans and is associated with several miracles involving bread [2] [3]. The community cherishes its personal ties to Georgia along with a strong cultural overlap between the saint’s Persian homeland and the neighboring Christian kingdoms of the South Caucasus. Through this shared ecclesial-architectural tradition, a thematic link was established. Therefore, the threefold identity of the community as one that is dedicated to St. Onuphrius, as one that provides a home for children, and as one that honors its ties to Georgia, formed the conceptual basis for the chapel’s design.

Architecture

Călin Chifăr explains:

Just as the iconographer begins the painting of an icon by first contemplating the saint—knowing his name, his features, his way of life, and his spiritual character—so too must the architect begin the design of a church… The patron saint provides the initial direction: shaping the character of the space, its orientation, and architectural features. This approach does not make each church a unique or isolated object, but rather, like icons—however varied—they all point to the prototype of the Incarnate Savior. In the same way, all churches, defined by their patron, ultimately refer to the image of the Heavenly Jerusalem. In this case, Saint Onuphrius the Great, a Persian-born ascetic who lived in the Egyptian desert, served as inspiration for the church’s structure. [4]

In the form of the building, one is impressed by a monumentality that reflects the spiritual greatness of St. Onuphrius, as well as a minimalism that reflects the ascetic austerity of his lifestyle. The broad central dome connects to the nave with no pendentives in between; there are no columns nor pilasters dividing the walls; there are no frames around the windows nor cornices between the registers. In fact, there are no architectural flourishes nor interior partitions whatsoever. Discreet lighting and a flat, circular chandelier reinforce the geometrical clarity. And the marble—whose subtle color and rhythmic veining were selected to complement the iconographic presentation—forms a floor and dado absent of artificial ornamentation.

This tension between monumentality and minimalism is an important principle in the architect’s creative vision. Chifăr initiated a dialogue with the principal collaborators to ensure mutual understanding from the beginning.

Two views of the Church of the Holy Cross, Jvari Monastery, which served as the main prototype of the church.

Sculpture

The works of sculptor Andrei Răileanu include the iconostasis, holy table, altar furniture, table of oblation, baptistry, and chanter’s stand. Vratsa limestone was selected for its soft beige color and material properties. The bread-like texture of the stone was produced by the bush-hammering process. Stone furnishings—unique among the region’s usual church furnishings—contribute to the sense of monumentality. And the restraint of the sculptor’s hand suggests a stillness in line with the saint’s hesychastic way of life.

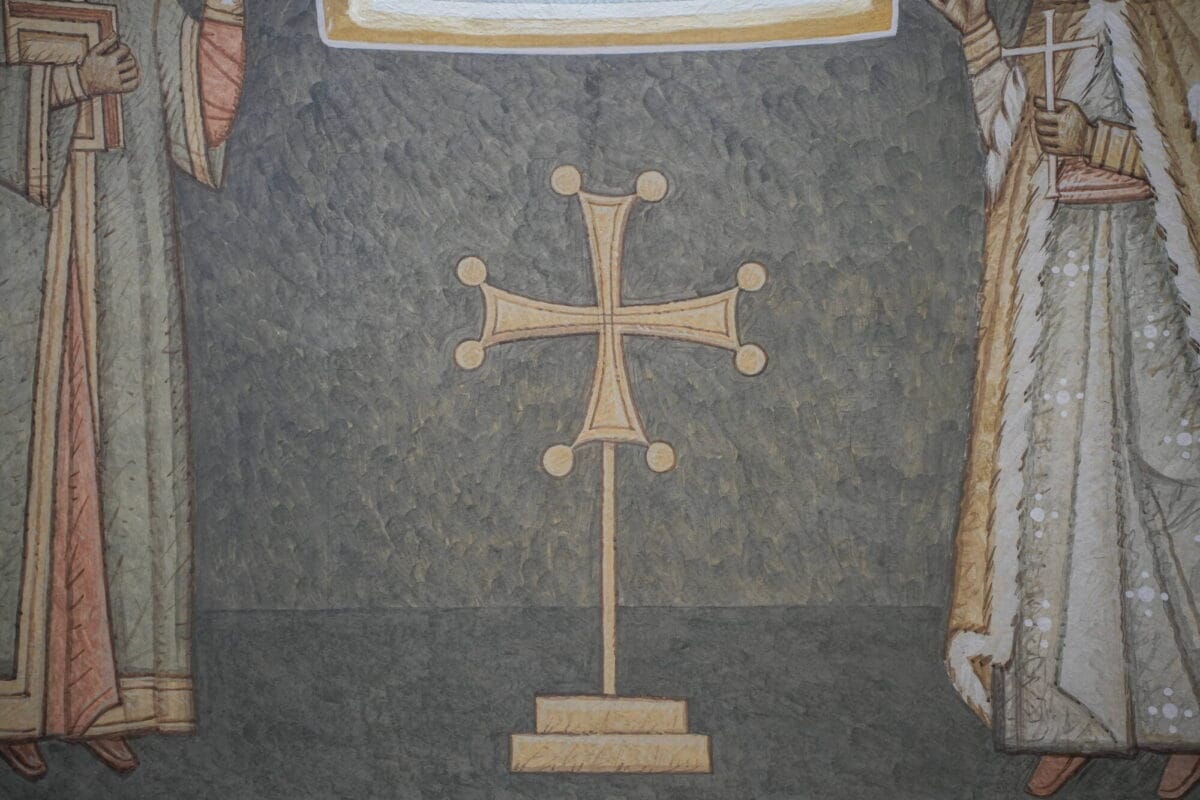

The octagonal form of the baptistry echoes the building itself, while motifs such as wheat and prosphora, carved into the iconostasis, are repeated in fresco. The iconostasis was designed in careful collaboration with the architect, who considers it not a piece of furniture, but a real structural element. The wide curvature of arches and the low-profile design preserve the circular rhythm and monumentality of the nave.

Painting

This church required novel solutions for the painting program. How, for example, could fully muraled walls with a normative dark blue background feel suitably light in such a monumental space? How could the circular rhythm be preserved when painted scenes and registers are typically separated by thick red borders? And how can the minimalism of the architecture be maintained when Orthodox church painting is so typically maximalist?

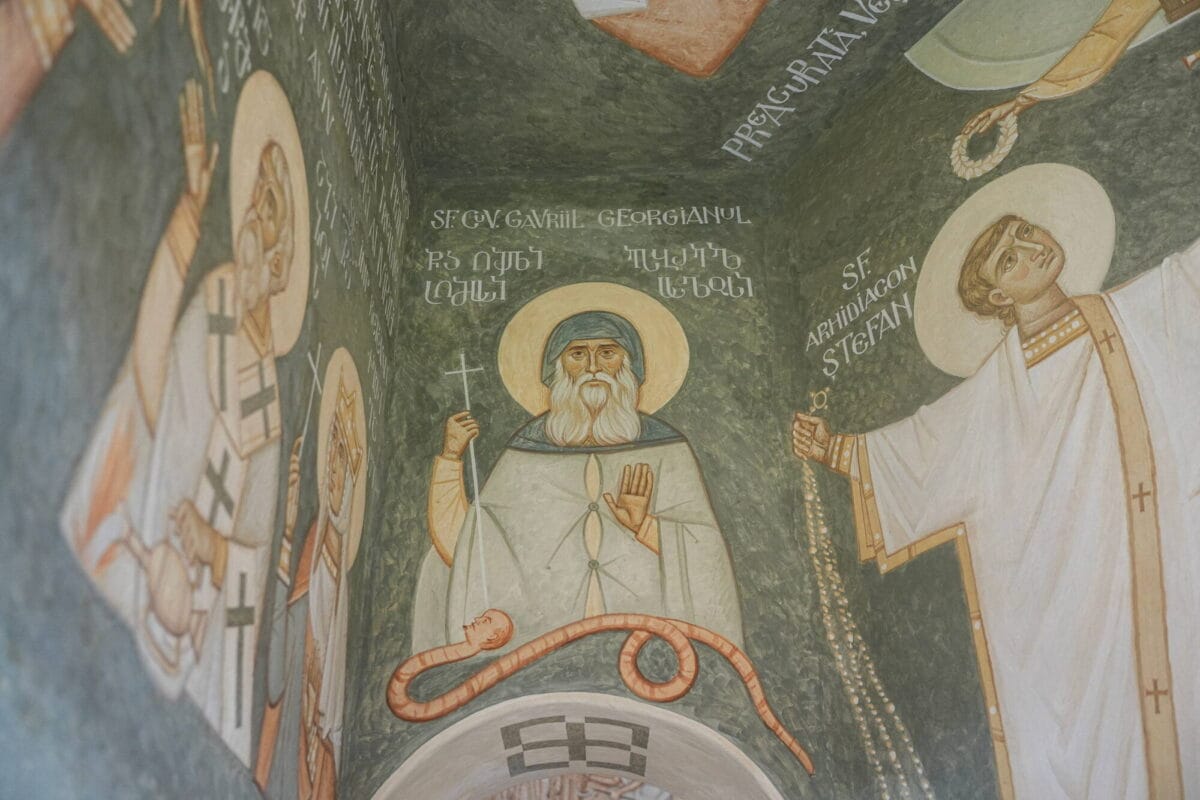

In addressing these questions, Andrei Mușat [5] developed a fresco approach featuring a desaturated palette, semi-transparent textures, and a lively painterliness. The result is wonderfully light and dynamic, and as one visitor commented: “playful, almost childlike.” Key is his minimal use of borders and ornamentation. There are no verticals to interrupt the movement of the eye. Horizontal lines are few. And thin yellow margins soften the edges of the apses and arches. Pure ornaments, often painted on architectural features and odd spaces (drawing attention to them) or as trompe-l’œil panels (creating features where they don’t exist), are severely limited. In place of such ornaments and borders, Mușat makes generous use of Scriptural quotations, allowing blocks and long strips of stylized text to function in their place.

Across the chapel, painting, sculpture, and architecture work together in a deliberate harmony that reflects the overarching vision of the architect, giving the space both monumentality and ascetic restraint while honoring the patron saint and the foundation’s mission. Other collaborators include Cristina Răileanu, who provided the iconography for the iconostasis and the table of preparation, which was painted directly onto niches that were carved into the stone. Fine lines and ample transparency elevate the beauty of the material, maintaining the sense of simplicity while providing consonant contrast to Mușat’s work. Sorin Albu assembled the mosaic of St. Onuphrius that stands above the entrance of the church, utilizing stone and glass tesserae that match the colors of the building materials. Furniture was selected with consultation from the principle collaborators, along with the textiles—designed by Atelier Bazgan [6]—that hang above the doors of the templon, cover the holy table, and adorn the clergy. Illustrator Astrid Mușat and restorationist Mădălina Mușat assisted with fresco work.

Much is owed to Fr. Visarion Pașca—the spiritual father of the local monastery and Foundation—whose visionary leadership made this project possible, and to Fr. Ioan Bizău—renowned art collector and professor of iconology—for helping to assemble and advise the team of collaborators. Fr. Ioan reflects:

What has been accomplished at Florești will become an important example in the national program of crystallizing an ecclesial art of Orthodox expression, intelligently applied to the local tradition and to the history of the parish or monastic community that assumes the uplifting labor of building what we call “the house of God.” [7]

The chapel of the St. Onuphrius the Great Foundation was sanctified on September 27, 2025 [8], on the Feast of St. Anthimos of Iveron [9], whose vita bridges his homeland of Georgia with Romania. The building demonstrates a rare example of a modern Orthodox church realized as a total work of art, where architecture, sculpture, and painting exist in iconic harmony.

- https://afso.ro/

- https://www.oramaworld.com/blog/lives-of-saints/saint-onuphrius-egypt/

- https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/0579/06/12/107799-venerable-onuphrius-the-great

- Original text: “Artistul iconograf își începe zugrăvirea unei icoane, cunoscând numele sfântului ce urmează a fi pictat, trăsăturile fizice, modul de viețuire, aspecte ale personalității duhovnicești. Asemenea arhitectul își începe proiectare unei biserici de la numele hramului care o definește și o personalizează. Hramul îi trasează direcțiile preliminare, caracterul spațiului, orientarea, trăsăturile arhitecturale. Această condiție nu le fac niște piese unice și izolate, ci precum toate icoanele, orișicât de diverse, trimit toate la prototipul Mântuitorului Întrupat, tot așa toate bisericile, definite după hram, trimit la icoana Iesalimului Ceresc. Astfel Onufrie cel Mare, un sfânt cu origini persane, nevoitor în pustia Egiptului a inspirat și structura lăcașului care împrumută prin centralitate și simetrie, morfologia bisericilor caucaziene.”

- Doctor and professor of Sacred Art at the University of Bucharest

- https://www.atelierdebroderie.net/

- Original text: “…ceea ce s.a realizat la Florești va deveni un exemplu important în programul național de cristalizare a unei arte eclesiale de expresie ortodoxă aplicată inteligent la tradiția locală și la istoria comunității parohiale sau monastice care își asumă truda înălțătoare de a edifica ceea ce numim ‘casa lui Dumnezeu’.”

- https://basilica.ro/biserica-asezamantului-pentru-copii-sfantul-onufrie-cel-mare-din-floresti-a-fost-sfintita/

9. https://orthochristian.com/7283.html

All photos used with permission from the authors.

If you enjoyed this article, please use the PayPal button below to donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

This is utterly wonderful in every way I can see.

Congratulations to all involved in the project, and thank you Jeffrey for the beautiful feature post.

My pleasure, Baker. Thank you for the compliment, I’ll pass it onto the team!

There are definitely some very beautiful elements here, but I fear that the desaturated pallet will not age well. It’s en vogue right now, and this church may feel very 2020’s in a handful of years.

That might well prove to be the case. It wouldn’t surprise me. But as long as it’s beautiful, how is that a problem? I’ve been in plenty of NeoClassical Russian churches that look so very “1810” and Art-Nouveau churches that are clearly from between 1900 and 1917. But the fact that I can identify their age from their style does not make them any less enjoyable. Quite the contrary. It would be boring if all churches looked so “canonical” as to all look the same.

As a professional stained glass artist and someone who studied art history, and as a visitor of many sites with many approaches of colour schemes in different periods of history, I agree with you Andrew.

The colours scheme or their tones also varies because of the colours communities find in the landscapes

the land surrounding them daily.

What counts most is the truth in the heart of the team work to share essential messages in harmony and with love.

What are some other recently painted churches with a desaturated palette? I wasn’t aware it’s en vogue. Appreciate your comment.

I feel rather under qualified to comment in this chat! This article, so elegantly composed, and the reality that this utterly beautiful church was recently built and painted and exists somewhere in this world, brings me the deepest peace and quiet joy! I wish I could spend a week praying there and absorbing its wonderfulness. I have sent the article to Bishop Erik Varden, a great intellect and scholar of the arts.

“And the restraint of the sculptor’s hand suggests a stillness in line with the saint’s hesychastic way of life.” I read this line again and again: perfect!

What a beautiful church, the muralist really has found a way to keep the dark blues full of light, and an especially masterful play of rhythm through all the figures and scenes. The directness of expression that makes them feel childlike is disarming without being distracting.

It is so wise for a church project to include an iconographer is the conversation early in the design process, though this is seldom practiced here in the US. Too often, a parish has designed and built a building before considering iconography, and they find that they have unwittingly placed obstacles in their own way.

This “Gestamtkunstverk” process, with all of the artists working together, is inspiring and I have only admiration towards it. But I would also like to say that, in some sense every church is gestamtkunstverk, in that it has all of these elements; architecture, painting, music, poetry, furniture and textiles – working together in one experience, even if aesthetically it is not a successful gestamtkunstverk. Maybe better put, in the liturgical life of a community, a parish church is doing something higher than Wagner’s concept aimed for, because the gestamtkunstverk is still a performance, taken in by a relatively passive ‘audience’; whereas in a church all these elements are in service of a fully participated relationship. I mainly wanted to add this comment, because I have seen that, though the love of a community in Christ, many times a beautiful organic unity can grow in a space where the design process was not as controlled.