Similar Posts

THE SACRED AND THE SECULAR

The Relationship of Orthodox Iconography and Gallery Art

Part 2: Gallery Art (here for pt.1)

The journey of an artist

At this stage in our story, by way of illustration I would like to be a little biographical. I will speak a bit about my own journey first as an artist in the world and then as an iconographer.

Though born in England, I was raised in New Zealand. Although as a child I had a modicum of education in Christianity, I ultimately came to believe in God’s existence through trees. In my childhood home there were splendid samples of trees and bushes in which my friends and I used to play hide-and-go seek and build huts. The many hours spent in their branches nurtured a deep respect and love for trees. Quietly I came to believe that a higher Wisdom must have made such splendid things. In them, function and beauty married. Trees were my proto-evangelists, leading me to belief on God.

It is pertinent that the Psalm verse set for feast days of Evangelists -“Yet their voice goes out into all the earth, their words to the ends of the world” (Psalm 19:4a) – is actually referring to the skies, to creation. The previous verses read:

The heavens are telling of the glory of God;

And their expanse is declaring the work of His hands.

Day to day pours forth speech,

And night to night reveals knowledge.

There is no speech, nor are there words;

Their voice is not heard. (Psalm 19:1-3)

In other words, the beauty of creation is a form of proto-evangelism.

This early experience of being led a step closer to God through creation is the seed of my belief in the importance of threshold beauty. In fact, in gratitude to trees for being my proto-evangelist, thirty years later I planted 5,000 native trees in the hermitage where I then lived.

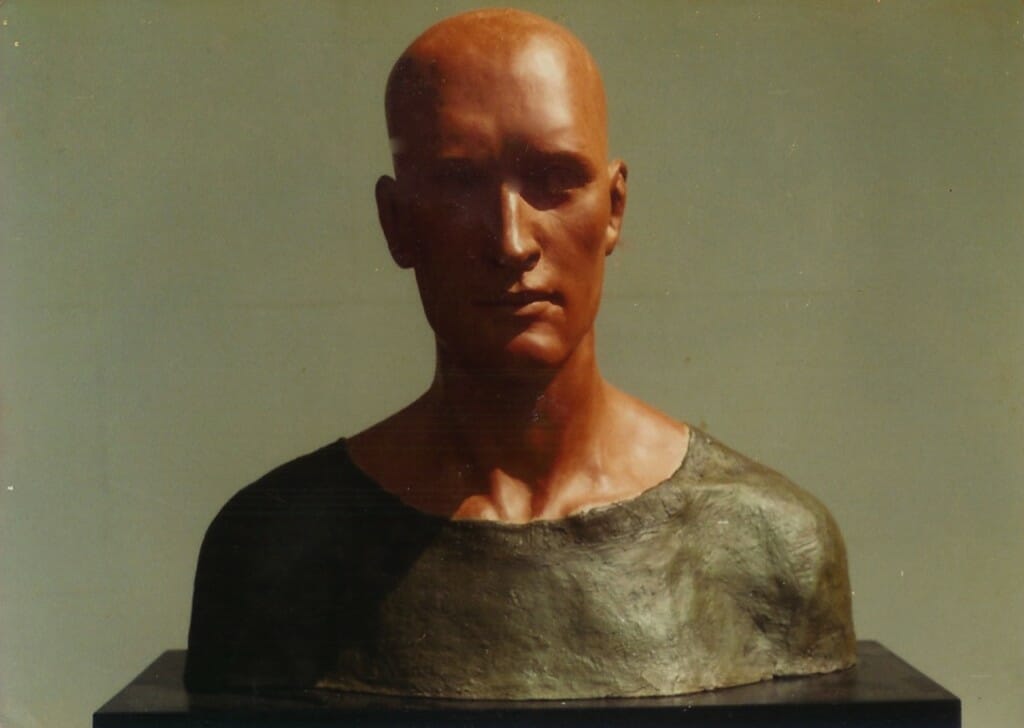

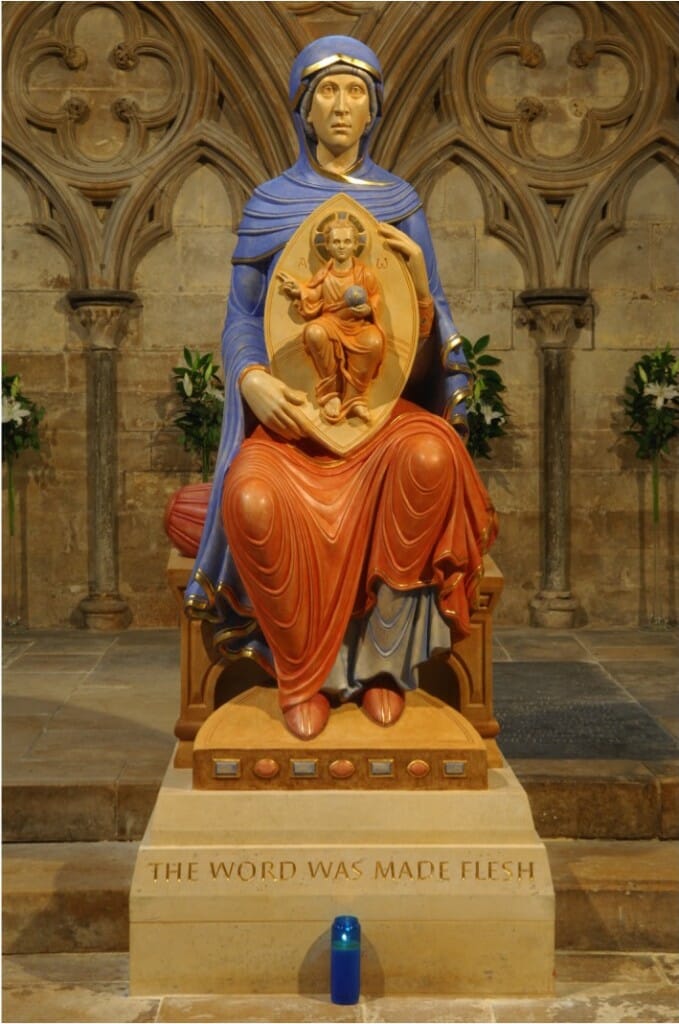

After graduating in literature and biology I began work as a sculptor, eventually going full-time. By then Christian within the Anglican/Episcopalian church, I was seeking ways to indicate in my sculptures the spiritual nature of the human person. Most of these works were not for church commissions but for gallery exhibitions.

This period reinforced for me the role of threshold art, art that was not overtly religious or liturgical but which might draw some people a little closer to at least a primitive belief in the spiritual.

As a Christian I wanted this spirituality to embrace the material world, not to be a flight from it. I felt that this incarnational approach was all the more important in a secular age which worshipped matter and where one could not assume any prior knowledge of Christianity.

There was a parallel in the then communist and atheistic Russia. I had heard that many people there began their journey to Christian faith with Buddhism. They could not take the step straight from atheism into fully-fledged faith, but they could took their first steps by following what is essentially an agnostic philosophical system, and one that did not require a communal and liturgical commitment as did Christianity. Having discovering some truth within Buddhism, but eventually finding it incomplete, many of these seekers then progressed onwards to Christ. I came to believe that the right sort of art, portico art, could do a similar thing, and so I wanted to make art that would affirm the numinous quality of life.

But before attempting this numinous quality I was convinced that as a sculptor one had to begin with technique and gain proficiency in depicting the material world, particularly the human body. Only then could one progress to suggest invisible realities. St Paul’s advice seemed pertinent: But it is not the spiritual which is first but the physical, and then the spiritual (I Cor. 15:46).

Since God had created both the material and the spiritual realms I believed that one would echo the other.

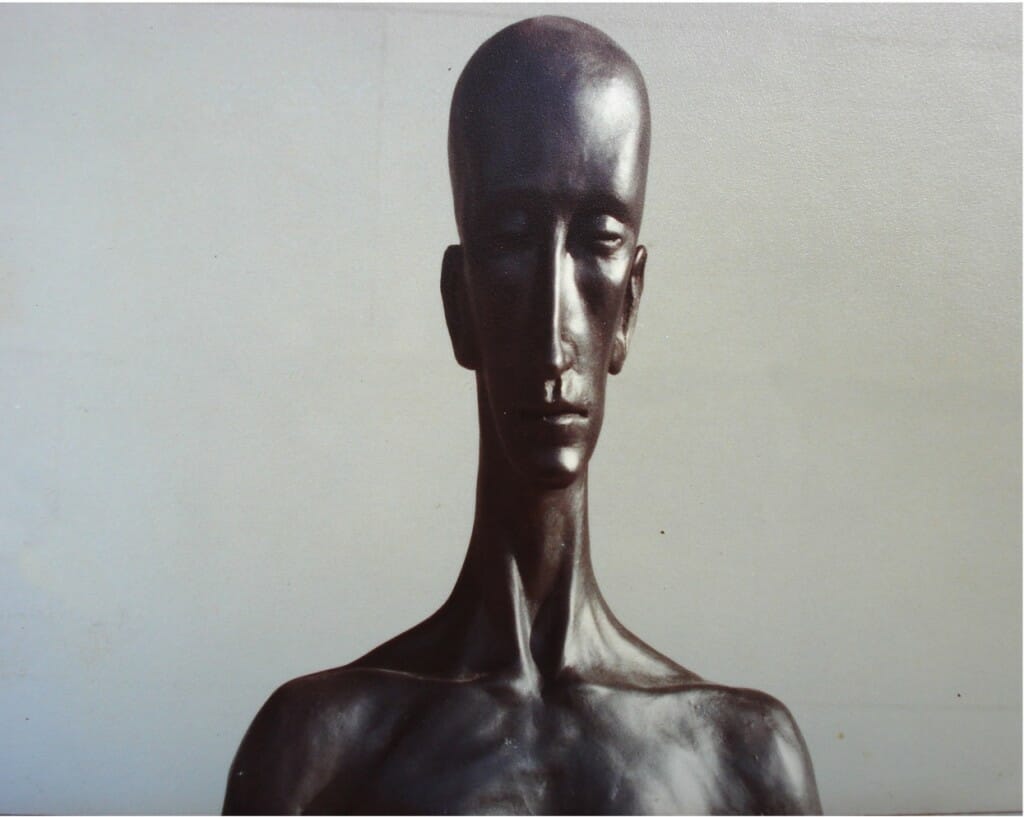

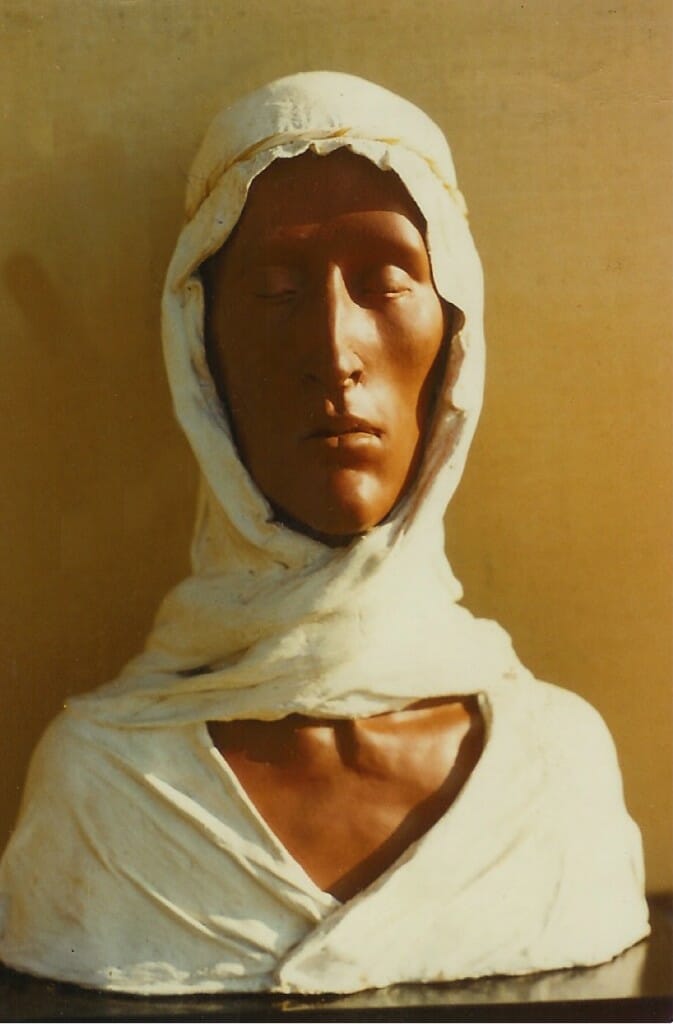

After mastering the essentials of modelling the human body, including making anatomical studies.

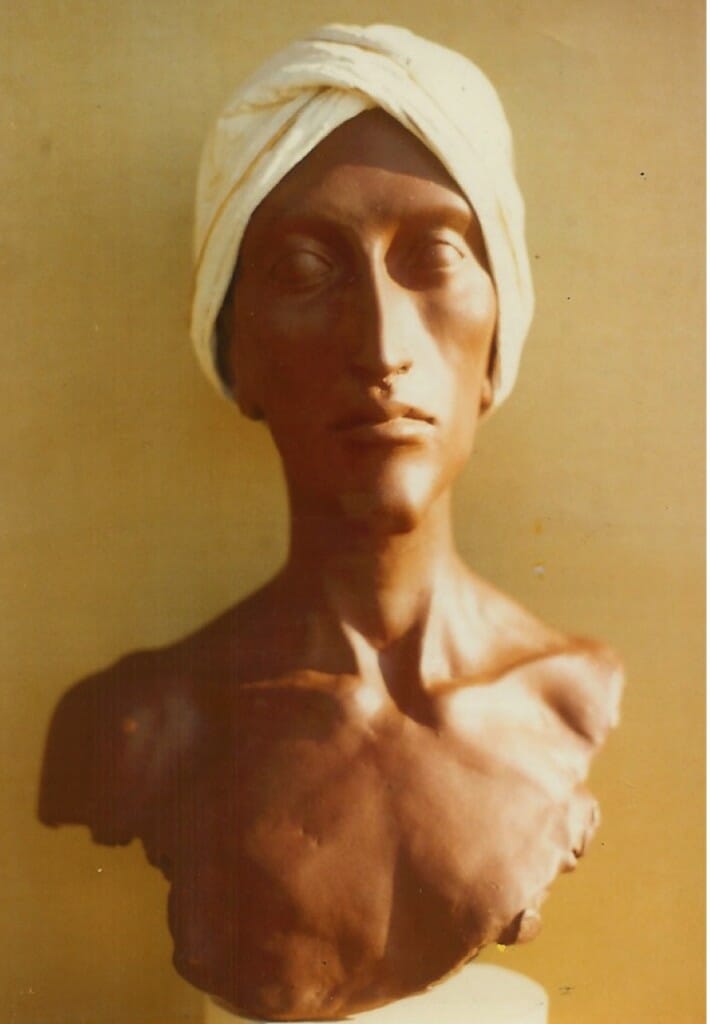

I then concentrated on how to indicate the spiritual nature of the human person. I tried varying degrees of abstraction.

To abstract means literally to “draw out”, and in its original meaning it denotes the discovery and manifestation of the essence of the subject, and not departure from reality as it tends to be understood today.

The art most influential for me at this stage was Egyptian and African work. Although perhaps too disembodied, too extreme in their abstraction, these sculptures helped me to reach some conclusions about how to indicate the spiritual. Most notably I learned the importance of a strong vertical axis or elongation; stillness rather than agitated movement; and emphasis on the eyes. Constantine Brancusi and Modigliani were also influences.

Having thus studied the two poles of figurative naturalism and abstraction I then sought ways of uniting them, of incarnating the spiritual in flesh. In retrospect I see now that I was trying to hint at holiness – essentially, to sculpt icons.

Gradually I came to some conclusions how to do this stylistically, but knew I still needed help in such a task. In due course a friend suggested that I should visit two Orthodox monks in New Zealand, one of whom was an icon painter. My friend said that icons did what I had been trying to do for some years. So I visited the monks, and found at their little monastery all that I had been seeking, both artistically, spiritually and historically.

In 1983 I was received into the Orthodox Church and soon afterwards returned to my birth place of England, where I began work as a full-time iconographer.

The last thirty-three years I have spent more or less full time as a liturgical artist, working first in relief wood carving, and then panel painting, fresco, stone carving, silverwork, and more recently, mosaic. But my earlier labours in pre-iconographic work as an exhibiting sculptor taught me the potential of gallery art to draw people a little closer to faith, to a sense of the numinous.

The Transfiguration. Our Lady of Lourdes Roman Catholic Church, Leeds, UK. By Aidan Hart, 2012. 20 feet high, fresco.

St Mary Magdalene and The Mother of God (unfinished). Detail from crucifixion for St George’s Orthodox Christian Church, Houston, Texas. By Aidan Hart, 2016. Mosaic.

How can gallery art operate as a portico to belief?

For me personally there are two types of artwork that do this: that which depicts suffering but with compassion, and that which suggests the world transfigured by light. The creators of such artworks are not necessarily people of faith, but they have grasped some truth in their search, and because this truth is an image of spiritual reality it elevates us.

Art of compassion

So first, compassionate art. Such works can help us see the divine image beneath suffering, and even behind ignorant acts. They show us that what makes us capable of suffering is also what makes us human. The Church Fathers tell us that although only holy people are in the likeness of God, all people are made in the image of God. It is precisely our God-given freedom that allows us to choose the wrong as well as the right. Compassionate artists do not idealise, but nor do they judge the wrong doer or feed on their suffering.

Dostoyevsky was the literary genius of such compassionate work, as was also the Greek writer of short stories, Alexandros Papadiamantis (1851-1911). In his short novel “The Murderess”, which is about a lady who kills the daughters of poor islanders so the parents don’t have to pay their dowries, without in any way condoning the murderous acts Papadiamantis somehow manages not to condemn or hate the woman herself.

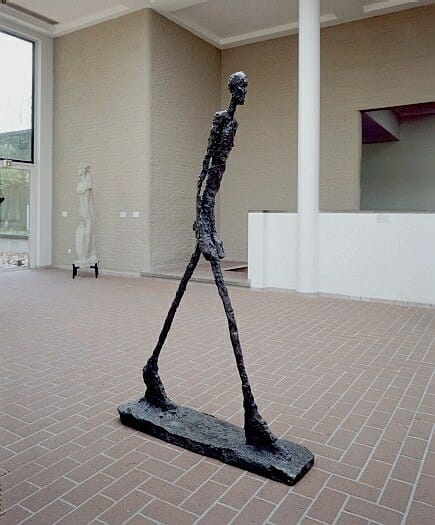

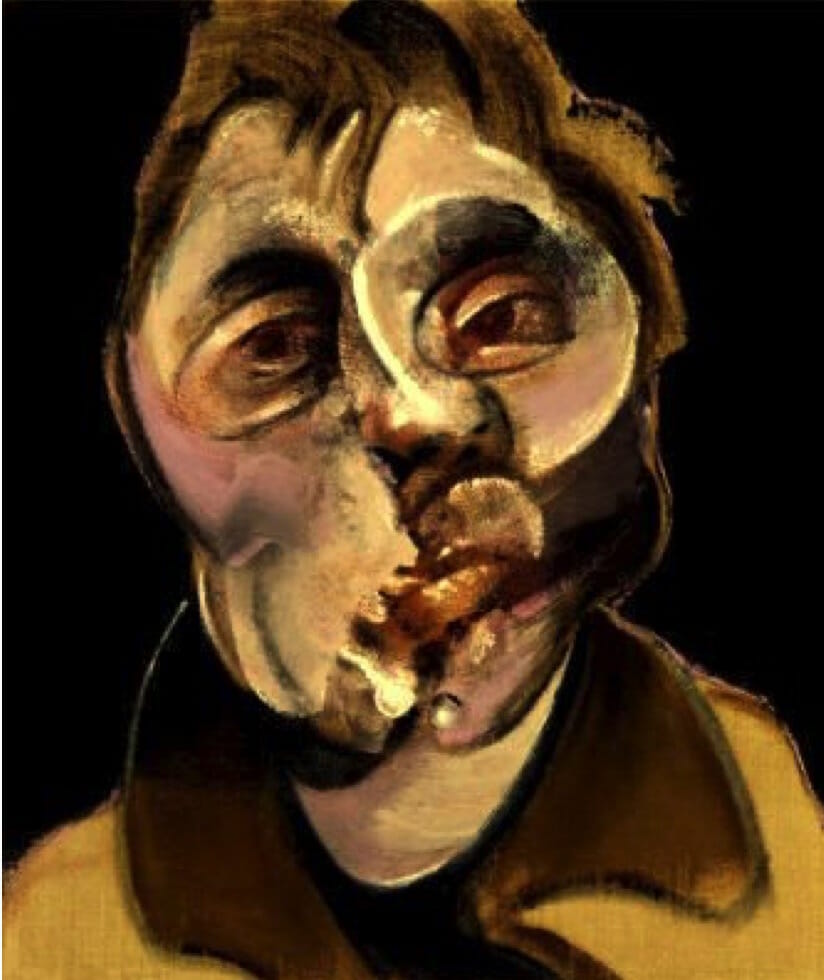

In the artistic realm, compare a Rembrandt painting, a Van Gogh, or an Alberto Giacometti sculpture with the works of Francis Bacon.

The first two indicate the suffering of humankind with pathos and compassion. Bacon on the other hand – despite his undoubted brilliance as a colourist and the visceral power of his work – seems to feed on the suffering and torment of his subjects. One feels that he needs suffering to feed his inspiration. Indeed he said:

The feeling of desperation and unhappiness are more useful to an artist than the feeling of contentment, because desperation and unhappiness stretch your whole sensibility.[5] (Francis Bacon)

It is true that great art needs a certain tension. Sentimentality and its consequent flaccidity is the bane of those trying to be positive in their art. But even iconographers, who are trying to suggest an harmonious world, feel the tension between aspiration and reality, the struggle to express both brightness and sadness, joy and sorrow, strength and gentleness. But to feed on negativity is different from depicting it with empathy and identity.

Art of illumination

Another form of threshold art is the art of illumination. Ascetic writers both East and West describe three stages in the spiritual life: purification, illumination and union. In the degree to which the soul is purified it experiences the created world illuminated by God’s grace, animated by the divine logoi or words that direct and sustain each thing. We see not just the bush, but the bush burning. In due course this leads the person towards union with God Himself, with the Logos who spoke the logoi.

Icons indicate this luminous grace symbolically by such things as gold lines on trees, furniture and garments, and of course also haloes and golden backgrounds.

Threshold artists will indicate luminosity in less symbolic ways. And most critically, they personally will not necessarily relate this light to God. But through their fascination with the way light interacts and animates matter they, perhaps inadvertently, hint at a world aflame with grace. The Impressionists are the obvious school that come to mind.

The Impressionists have been criticized for being somewhat too sensual in their depiction of nature, even sentimental. Most Impressionists were not particularly religious people, but I suggest that their preoccupation with the interaction of light with matter meant that they inadvertently hinted at a transfigured world, a world not just reflecting light but radiating light. One feels just this when standing before a Monet haystack, as also a Van Gogh sunflower, landscape or farmers.

First Steps, after Millet. Vincent van Gogh, 1890. “I want to paint men and women with a touch of the eternal”.

The light seems to emanate from within these objects and not merely reflect off their surface.

Unlike the Impressionists, Van Gogh was quite deliberate about the spiritual aim of his painting. He wrote:

And in a painting I’d like to say something consoling, like a piece of music. I’d like to paint men or women with that je ne sais quoi of the eternal, of which the halo used to be the symbol, and which we try to achieve through the radiance itself, through the vibrancy of our colorations…[6]

And in the sculptural realm Constantin Brancusi too was conscious of his purpose. He wrote:

The artist should know how to dig out the being that is within matter and be the tool that brings out its cosmic essence into an actual visible essence. [7]

Might not such an art of illumination help keep alive in us nostalgia for the paradise that is our true home? What is the fall if we do not know the heights from which we have fallen? What is paradise lost if we have forgotten paradise? What is salvation if we do not know into what we are being saved? If hell is darkness, then it is a place where luminosity is absent, where all appears without light, where we experience the flame of the bush without its light.

From prophecy to evangelism

In conclusion, we ought to have no time for a religiosity that wants to keep us enclosed within church walls, makes us fearful of the outside. True faith finds and rejoices in the good wherever it is found. As Saint Paisius of the Holy Mountain taught me, a healthy soul is like a bee that seeks flowers and ignores rotting flesh. An unhealthy soul by contrast is like a fly that ignores vast fields of flowers and is attracted to a little rotting flesh.

One task of the Church is therefore to find the partial good in its surrounding culture and bring it to fruition. In this respect, living as we are in an increasingly non-Christian but educated epoch, our task is akin to that of the Apologists of the first centuries after Christ. They sought for truths in the Greek philosophy of the time, putting aside what was wrong, adopting what accorded with truth, and adapting what was partial. We need to embrace this creative and theological activity in our own times.

Some contemporary icon painters have done the same with modern art, most notably Gregory Krug.

Whether or not he consciously adopted aspects of modern art, the fact remains that his unique icons could only have been made in the 20th century. Dr. Isaac Fanous certainly adopted aspects of Cubism into his Neo-Coptic iconography in a deliberate synthesis of old and new.

A prophetic assessment of a culture will not always of course be affirmative; it will also be critical. I suggest, for example, that an Orthodox Christian’s reading of art history will differ from the dominant narrative of secular scholarship. Scholarship reveals facts, but these facts need to be interpreted. Too often, for example, the history of art has been measured against the assumption that naturalism equals realism. So Byzantine art is considered without perspective, while Renaissance to be the champion of proper perspective.

In reality, Byzantine art uses five or six systems of perspective. These offer a far richer palette with which to express spiritual reality than the mathematical one-eyed system propagated by the Renaissance.

They also accord more closely with our subjective experience of reality. For example, even though I do not see both sides of a building I know that they are there, and therefore the icon will often depict these sidewalls simultaneously through its multi-view perspective. Unlike single view perspective, icons depict what we know and not just what we see. This is in fact the metaphysics behind much of early modernism, which reacted against the neo-Classicism then dominant in Europe.

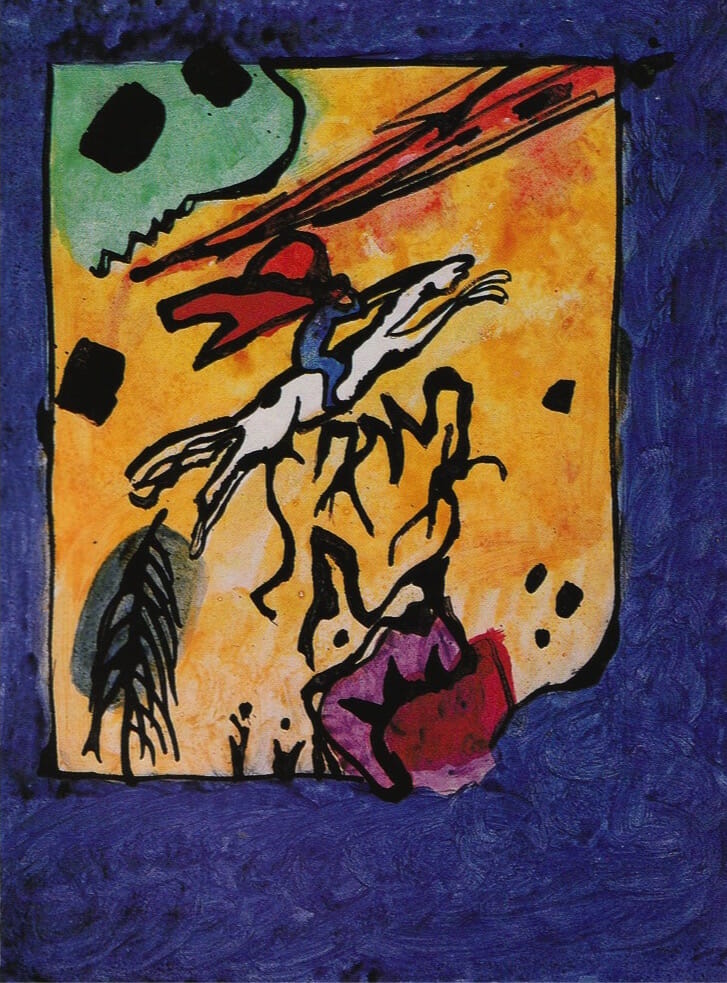

The secular art historical narrative has also been too silent about the spiritual impetus behind much of the early modernist movement. Kandinsky for example was quite articulate about the spiritual aims of his art, most notably in his work “On The Spiritual in Art”, which was particularly influential in its English translation. Although perhaps more a Theosophist than an Orthodox, his Orthodoxy nevertheless informed a lot of his thinking, and sometimes, as in his “Sketch with Horseman”, icons provided inspiration for his compositions.

Sketch with Horseman. Vasily Kandinsky, 1911, showing the influence of icons, in this case, Elijah in the fiery chariot and St George slaying the dragon.

For Kandinsky painting was a spiritual exercise with spiritual aims. He wrote:

The artist must train not only his eye, but his soul.[8]

The world sounds. It is a cosmos of spiritually affective beings. Thus, dead matter is living spirit.[9]

We have already discussed the consciously religious basis of Brancusi’s work. (for more discussion see my article “Constantin Brancusi” in http://aidanharticons.com/category/articles/).

The Scriptures and the history of the Church teach us that the best missionaries first discover what God has already revealed to the culture they are addressing, and only then begin to proclaim the Gospel. These evangelists are first listening prophets and seeing seers, and only then preaching missionaries. They perceive the words of God already accepted by the people and then try to take their listeners to the next stage.

Although St Paul was indignant about all the idols that he saw at the Areopagus, he began his address not by condemning his listeners for idolatry but by praising them for being so religious. He went on to base his message on their inscription to “An Unknown God”. He built his Gospel narrative on this germ of truth, even quoting their own philosophers and poets.

———————————————-

[5] Quoted in Art, Robert Cumming (DK, London, 2005), page 433.

[6] Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo van Gogh, 3 September 1888, (Letter 673), in Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters. http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let673/letter.html.

[7] Brancusi, in F. Bach, M. Rowell and A. Temkin, Constantin Brancusi. MIT Press, 1995. Page 23.

[8] Quoted in Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art (New York, 1994), eds. Kenneth C. Lindsey and Peter Vergo, page 197.

[9] Kandinsky, in “The Blaue Reiter Almanac”, quoted in Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art, page 250.