Similar Posts

THE ALTAR AND THE PORTICO (PT.1)

The Relationship of Orthodox Iconography and Gallery Art

Part 1

(This is the a talk given at Sacred And Secular In Life And Art, Oxford, a workshop dedicated to the memory of Philip Sherrard. St Gregory’s House, Oxford, 14-17 July, 2016.)

Introduction

Unlike most of the esteemed speakers at this gathering I am not a scholar but just a practising iconographer. I was also, before becoming a member of the Orthodox Church, a sculptor. So I would like to share some of my reflections about the relationship between liturgical worship – what goes on within church walls – and daily life and culture beyond those walls. In particular I will explore the relationship between liturgical art and art in the wider world – what we might for convenience call gallery or secular art.

In my reflections I would like to regard the term secular not in its pejorative sense, as the bad world outside the Church, but rather in its earlier sense as the larger world in whose midst the Church is planted to transfigure that world.

In considering our subject of sacred and secular we may have the image of a splendid garden city expanding into a wild jungle, rather than a fortress sealed off against siege from the world. This city does indeed have walls to keep bad things out, but it also has gates, and from its heart flows a River that brings life wherever it flows, as the prophet Ezekiel tells us in his vision (Ezekiel 47).

Eden within the forest

An iconographer begins in the beginning, with the raw material of pigment and egg, or of rough matter waiting to be carved. So on the subject of the sacred and secular I would like to begin at the beginning, with the story of creation. Rather presumptuously I will dare to paraphrase the Genesis account to illustrate how I understand our subject.

God created the world a luxuriant forest, and in its midst He planted a garden. This garden was His special artwork. The wild world outside was His palette, and the garden was His painting.

This garden of Eden was also a gift, a gift to His bride to be, for He gave this garden to us as our home.

Walk with me, let us commune together in my garden, He says.

But I have also given you a task. Expand this garden. Make the forest beyond even more beautiful. Cultivate it into garden. Make the good very good.

I do not know how you will design this extension of My own garden, for I have made you princes and princesses. I have granted you freedom and power to cultivate your world.

Only remember that this beauty is a gift, an expression of My love for you. Give thanks for all things and this world will be for you the tree of knowledge of good. It will be for you a communion of love, life and light.

But if you treat this world as a thing, it will be for you knowledge of evil. It will no longer be My engagement ring to you but a mere lump of gold and diamond, no longer a gift but dead matter.

If you live a life of thankfulness, in due course you will be ready to eat from the Tree of Life and live forever. By it you will become all light, all true, all love, a bush burning without being consumed. You will become flesh aflame. You will become gods by grace.

I have given to you each thing and creature. Name them so that you can have a relationship with them, and with Me through them. By each naming you will discover another line in My poem, for the cosmos is My poem written to you.

Discover each thing’s specialness, its inscape, its logos. By this you will know how to use each thing as you cultivate your paradise, a gift to me. In it I will walk together with you and with your children.

The sacred as source

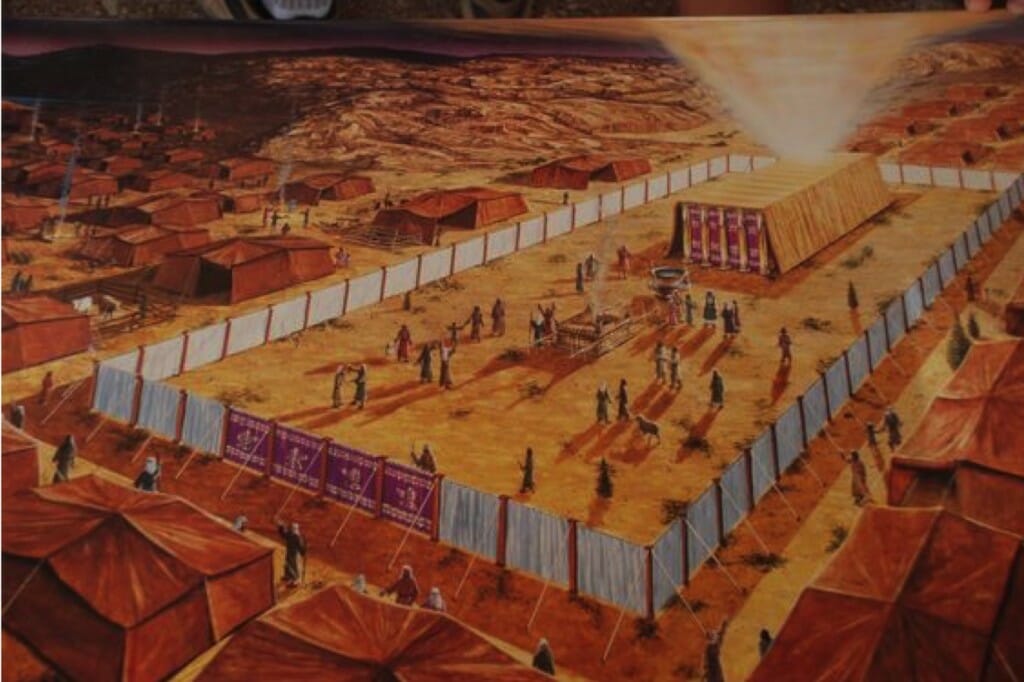

Throughout the Old Testament God gave the Israelites specifically holy and sacred things, such as the ark of the covenant, the tent of meeting and the showbread.

He also gave them specifically sacred people: the patriarchs; the prophets; the psalmists. But these were given not to condemn all else to mundanity. These things and people were “set apart” to act as the initial conduit of holiness for all. When the elders complained to Moses that there were people prophesying outside the camp, beyond the tent of meeting, he replied that he wished that all the Lord’s people would be prophets. Metropolitan Kallistos Ware has said that one is Priest (Christ); some are priests (the clergy); all are priests (the priesthood of the laity).

And so it is that I believe liturgical art exists to help us live our whole lives liturgically. A church temple, as St Maximus the Confessor affirmed, is an image of the whole world. This splendid earth was created by God to be our temple within which to worship Him. Church buildings exist simply to remind us of this. Through His incarnation God the Word has united the world with His divinity. As St Maximus the Confessor wrote:

And with us and for us, Christ embraced the whole creation through what is in the centre, the extremes as being part of Himself, and He wrapped them around Himself, insolubly united with one another: Paradise and the inhabited world, heaven and earth, the sensible and the intelligible, having Himself like us a body and sensibility showing that the whole creation is one, as if it were also a man, achieved through the coming together of all its members… [1]

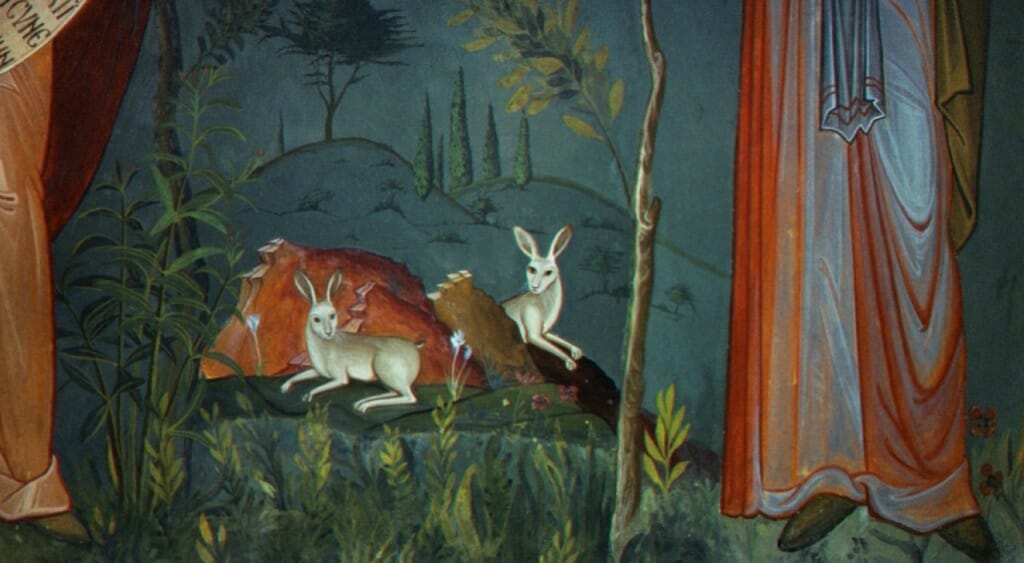

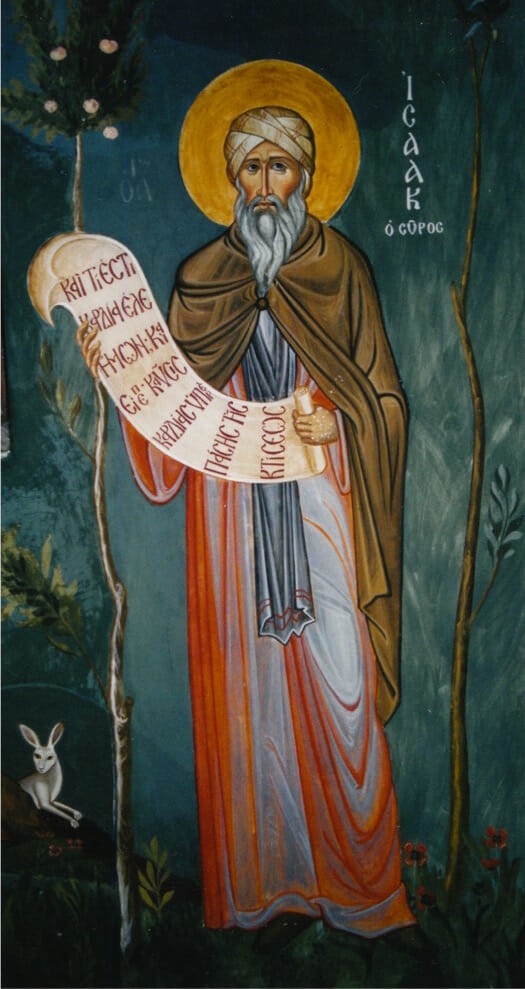

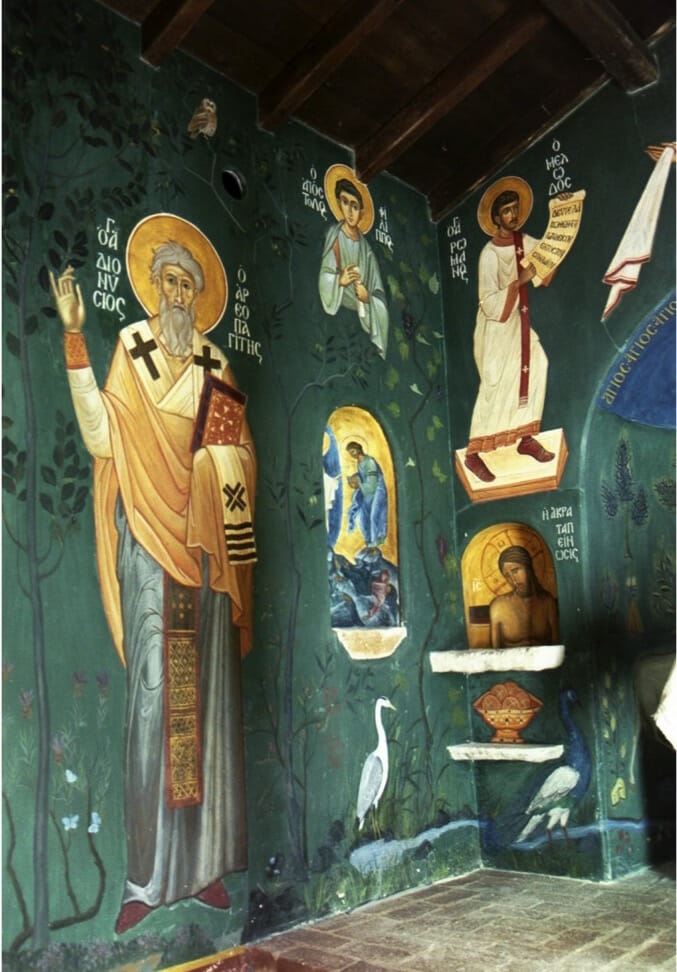

I experienced this “coming together” of heaven and earth personally when I was frescoing Denise Sherrard’s chapel at her home in Evia, the chapel of the Life Giving Spring that she and Philip had built. We wanted to reflect Philip’s affirmation that the material world is an integral part of the spiritual life,[2] so I painted a tree between each standing saint. Some of the saints are also accompanied by a creature associated with their lives: St Melangell with a hare; St Mary of Egypt with the lion which dug her grave; bees with St John the Baptist who ate honey while in the wilderness, and so on.

Lion, below fresco of St Mary of Egypt. Chapel of the Life Giving Spring, Evia, Greece. Aidan Hart. Fresco.

Hare, below icon of St Melangell of Wales. Chapel of the Life Giving Spring, Evia, Greece. Aidan Hart. Fresco.

I modelled the frescoed trees on the trees that grew outside the chapel. As I worked many hours each day in the chapel the awareness grew that the world is indeed created to be a temple, designed to inspire us to praise and love its Creator. The vision of paradisiacal trees that began inside that small chapel’s walls continued when I continued my life outside. The sacred transformed the secular, paradise extended into the ‘jungle’.

Importantly, this sense of continuum was supported by Denise’s attempt to express love for God’s creation in her daily life and to live life gently upon His earth. The food we ate was prepared with love, much of it grown in Denise’s own garden. Even the wine was homemade. The chapel itself had been made of local stone.

Immersion in the paradise of church worship affects the way we design our day-to-day lives outside the services. The architecture of our houses, our furniture design, our hospitality, our music – all aspects of life – can take their inspiration from the Liturgy. The Liturgy is like our tuning fork, helping to keep our daily lives in harmony with heaven’s.

Heaven’s music

When our inner music harmonizes with heaven’s then we will naturally fashion utensils, furniture and homes so that they harmonize with our human nature made in God’s image. During the making of an icon one is constantly making aesthetic decisions based on what will best harmonize with this inner sense, what will be conducive to prayer and what will not. In the same way we can design our dwellings and public places to lift our souls, to nourish us. Such buildings will fit the image of God like a well tailored garment.

Having this inner music we will create a culture that will not only function well but will delight the eye and bring forth the logos or character of each raw material. I have a book of traditional Balkan houses, and in it is a photograph of a Rumanian kitchen. The carved wooden utensils shown there could just as well be on display as exquisite abstract sculptures in a gallery. In fact, in these and in the carved wooden columns outside one can see the inspiration for the sculptures fashioned by the father of modern abstract sculpture, Constantine Brancusi.

As he wrote:

They who have preserved in their souls the harmony residing in all things, at the core of things, shall find it very easy to understand modern art, because their hearts shall vibrate in keeping with the laws of nature.

This relates to what St Maximus the Confessor wrote some fourteen centuries earlier:

Do not stop short of the outward appearance which visible things present to the senses but seek with your intellect to contemplate their inner essences (logoi), seeing them as images of spiritual realities…[3]

Brancusi was well acquainted with the liturgical life of the church, and this, along with Rumanian folk art and architecture, had a profound influence on his work. According to the biography written by his friend V.G. Paleolog (Tineretea lui Brancusi or The Young Brancusi)[4] Brancusi spent many years as a church server and chanter, beginning from the age of eleven. Later while an art student in Bucharest, aged 28, he was again a chanter, well respected for his pure tenor voice. Later, from 1906 to 1908, he sang and served in the Rumanian chapel in Paris, the same chapel in fact where his funeral was held according to the Orthodox Church’s rites in 1957. He evidently held the hymns that he chanted in high regard, believing them to possess metaphysical depth:

I know that the prayers of our old Oltenians [Brancusi came from the county of Olt] were a form of meditation, that is to say a philosophical interrogation.

Once when his friend Petre Pandrea was praising his sculpture, Brancusi replied that all he had done was to set up a branch office of Tismana Orthodox Monastery in Paris. He saw his sculptures as an extension of the worship and ascetical life of that monastery. The sacred informed the secular.

Culture as the Liturgy of Preparation

As we shall explore a little later, this transformative process also works the other way: the art of life lived outside the temple walls should act as a portico, preparing us for entrance to the inner sanctum.

Our daily life can be an extended beginning to the first part of the Holy Liturgy, the Service of Preparation. For the bread and wine we offer is the work of human culture. By our endeavour we humans transform God-given wheat into bread, and grapes into wine. But this transformative process does not stop there. The bread and wine turn is offered within the Liturgy at the Great Entrance, and through the calling down of the Holy Spirit, the epiclesis, they become the Body and Blood of Christ.

Every aspect of our daily living can be seen as this same transformative process, culminating in the Holy Liturgy’s deification of the bread and wine. This is suggested by the etymology of the word culture, which stems from the Latin word colere, which means to inhabit, care for, till, worship. Culture then becomes cult, an act of worship. Culture is both tilling and working and worship.

Any failings in our modern culture are ultimately due to our failure to continue work into worship, to carry the cultivation of the land into the cult of the liturgy.

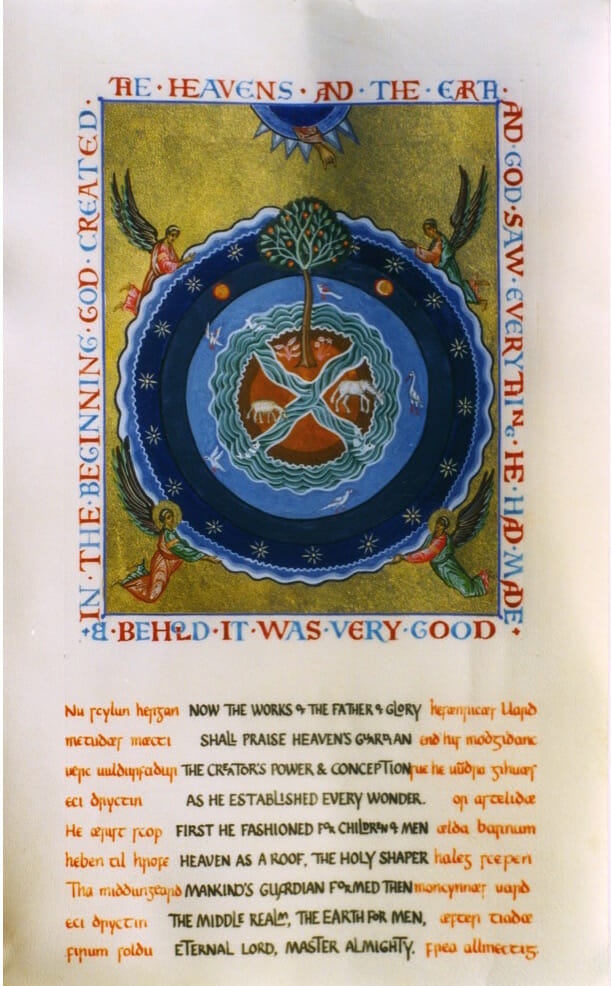

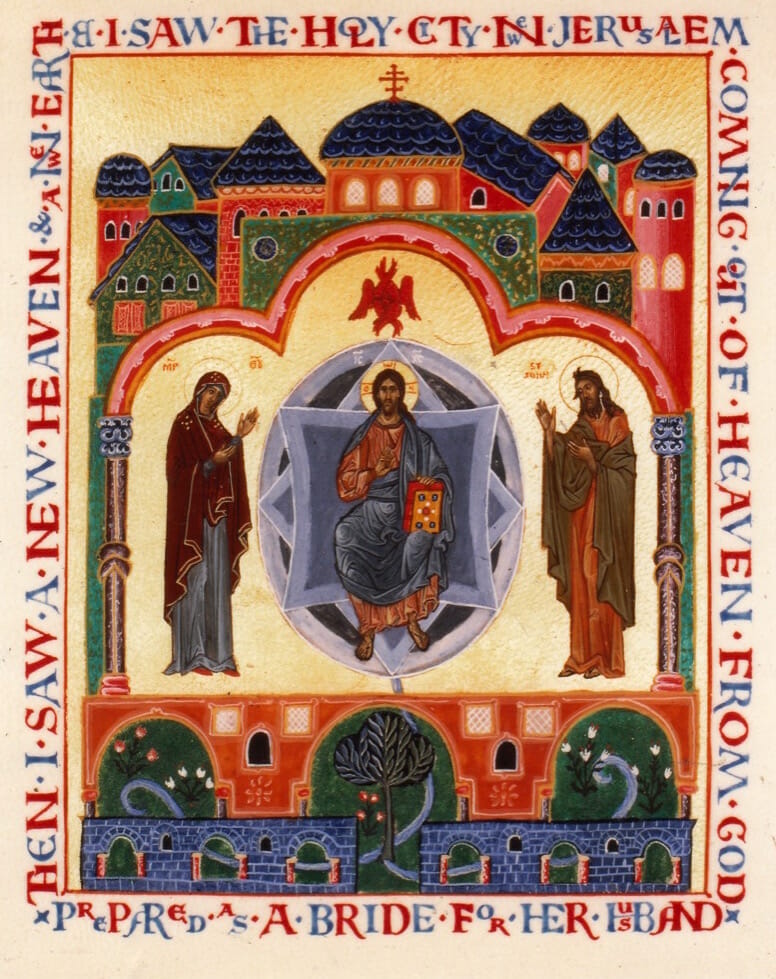

The New Jerusalem

To return to the beginning, to Eden. The Scriptures begin with this garden but they end with a city, The Holy City “coming down out of heaven from God, like a bride adorned for her husband” (Rev. 21:2).

A city, like a garden, is the result of a wild world transformed. Rocks become building stones, clay become bricks, trees become timber.

We are used to cities being the antithesis of goodness, to be like Babylons. But this only happens when their makers do not have the music of paradise within themselves, when they do not have an inspiring and appropriate prototype. This New Jerusalem is The City. It is the archetypal city that can be the inspiration for our labours and life in this age.

What then is the essence of this archetypal city? The Scriptures tell us that it “has the glory of God and a radiance like a very rare jewel” (Rev. 21:11). That is, it is deified. It is not mere matter, not mere humanity, but matter transfigured, humanity deified.

It is pertinent that the original Greek word translated in this chapter as adorn – “like a bride adorned for her husband…the foundations of the city were adorned with every jewel” (21:2 and 19) – is kekosmimenin/oi. The word is derived from kosmos, which is also the Greek word for the universe. So the Greek understood the universe is adornment.

But who is it adorning? The whole world was created to be an adornment for the Body of Christ. By becoming the garment for the Body of Christ the world can be transfigured, become glory bearing in a way that it was not before. The sacramental life of the Church can in fact be likened to the weaving of a garment for the transfigured Christ.

Prepared by thanksgiving (remember the tree of knowledge of good and evil of which we spoke in the beginning), we may in due season eat of the Tree of Life and become gods by grace. And through us, all the cosmos becomes brilliant, like the twelve jewels that adorn the foundations of the New Jerusalem.

And we must remember that these jewels are many coloured, each unique. Union with God does not eliminate each person’s and each thing’s distinctiveness. To the contrary, grace brightens uniqueness, clarifies it of ego and sets it in relationship with the other colours. Poems need distinct words. There can be no union without distinction, no community without persons.

Sant’Apollinare in Classe

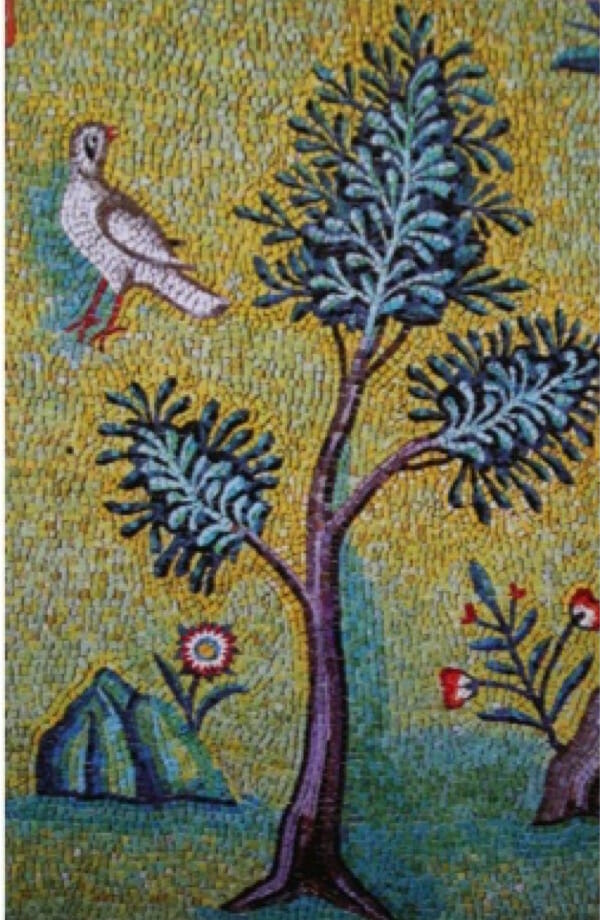

One of my favourite mosaics is that found in the apse of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, in Ravenna (created c. 534 AD).

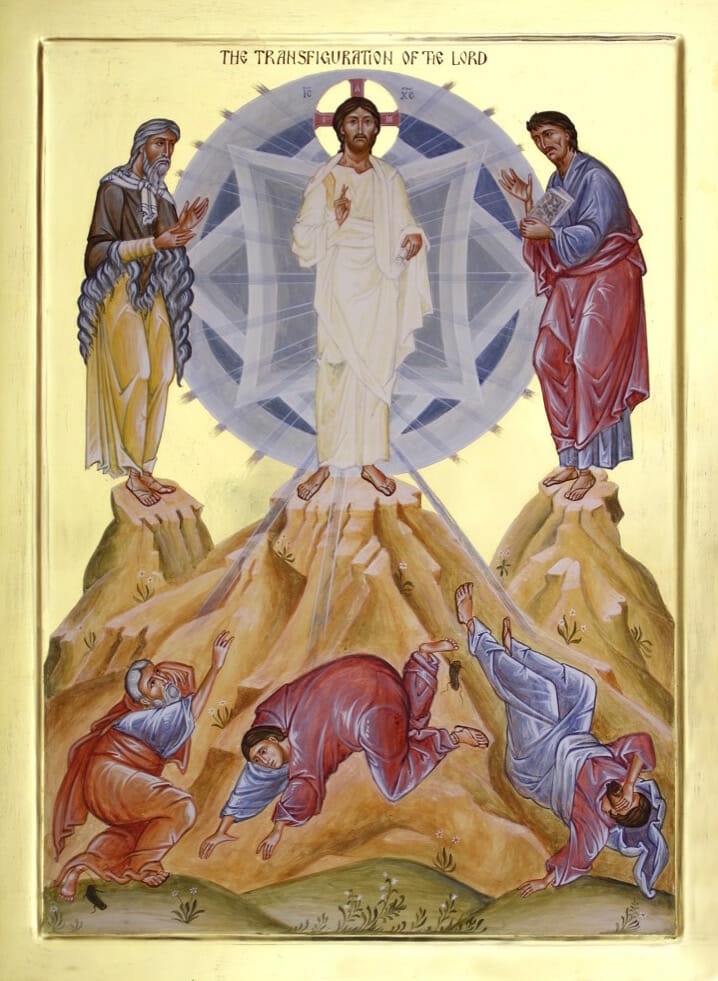

Sant’Apollinare in Classe apse (c. 534 AD). The Transfiguration; Paradise; the Second Coming; The New Jerusalem; Our Priestly role

It is an image that combines paradise, the transfiguration, the Eucharist, the Second Coming of Christ and the New Jerusalem.

In the midst of the garden stands Saint Apollinare, dressed as a celebrating bishop and with his hands raised in the prayer of epiclesis, calling down the Holy Spirit. A sea of gold is above the expanse of the emerald green landscape. Its golden light breaks forth into the world below, in the yellow tinted tesserae around the rocks and trees and in the brilliance of the white sheep and vestments of Apollinare.

The tree tops of the garden in turn reach up into the golden heavens, spirit and matter overlap.

Although it is not immediately evident, this mosaic is in fact an image of the historic transfiguration of Christ on Tabor. We see Moses and Elijah above. The three sheep represent Peter, James and John.. A vast gold cross with a small image of the Pantocrator within a roundel represents the transfigured Christ. The hand of God above suggests the voice of the Father heard by the disciples on Mount Tabor.

But this mosaic is also an image in our present age, when the world is being transfigured through the Eucharistic life of the Church. The celebrating Saint Apollinare represents in himself the whole worshipping Church, giving thanks for all things. He, and those celebrating the daily Liturgy in his church, are doing what Adam and Eve failed to do.

The mosaic is also eschatological, for it depicts the Second Coming of Christ. Why so? Because of the sunrise-coloured clouds above and the vast golden cross.

Most early mosaics in Rome show Christ in His second coming, and they too sport these brightly coloured clouds to suggest a sunrise. The vast cross also implies the Second Coming, for Christ Himself says that His coming will be preceded by “the appearing of the sign of the Son of man in heaven”, which Church tradition tells us will be the sign of the cross:

… then will appear the sign of the Son of man in heaven, and then all the tribes of the earth will mourn, and they will see the Son of man coming on the clouds of heaven with power and great glory…

(Matthew 24:30)

The mosaic goes even further, and hints at the subsequent descent from heaven of the New Jerusalem. Bethlehem and Jerusalem are depicted to the left and right of the triumphal arch to suggest the beginning and culmination of Christ’s divine dispensation. God enters the world in humble Bethlehem, and transforms it into the New Jerusalem. Indeed, icons of Christ’s nativity seem to emphasise this contrast, for they depict Bethlehem as a rocky and barren place, awaiting its transformation into the New Jerusalem. Christ is the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end.

But we must remember that this city to come is verdant. It is a garden as well as a building. There is a river in its midst, flowing from the throne of God, “and either side of the river is the tree of life, with its twelve kinds of fruit” (Rev. 22:2). This city does not replace the garden of Eden, but is its fruit, its culmination. It contains the garden and does not replace it.

Portico and Nave

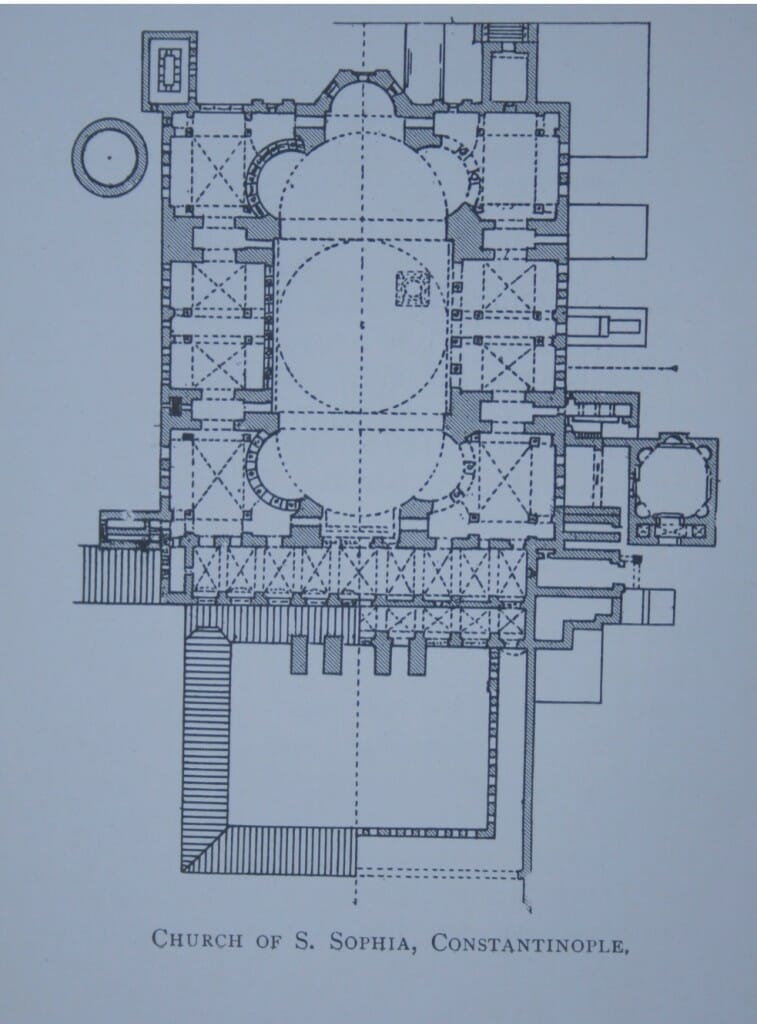

In most of our churches today we have a rather rude transition from exterior to interior. But in most early churches it was not so. Most had a portico, a place colonnaded around, roofless yet walled.

In the centre a fountain gushed forth fresh water. This fountain might also have been surrounded by a cloister type a garden. We can still see such porticos in Rome, as at San Clemente, and garden courtyards, as in Saint Cecilia’s in Trastevere.

Walking along the busy street you would spy this little paradise courtyard and be drawn towards its coolness and stillness. Once within this portico, through the open doors of the church you would eventually see hints of some glittering mosaics or wall paintings, and pins of light from oil lamps. So you would be drawn further in.

Once inside this exonarthex you would perhaps see images of the six days of creation, or the prophets, or, as in Iviron monastery, the Psalms of Lauds illustrated, where all creation is praising God.

You might also see images of the day of judgement, reminding you that repentance and purification is needed to stand the glory of God’s light which can be experienced further inside.

After looking around these scenes you would see yet another door, and enter the narthex, where you would see perhaps frescoes of standing ascetics.

Eventually you would be drawn even further, into the nave. In this broad yet intimate place you find yourself surrounded by angels, saints, scenes in the life of Christ. You might even see a mosaic floor, the world of geometry made into a dance of stone tesserae. If you were there during a vigil you might see the chandeliers swung, as though obeying the command given to the heavenly bodies, to “praise God sun and moon, praise Him all you stars and lights.” This nave might be small, as in this small chapel I made from an old barn, or large, as in an Athonite catholicon.

Beyond even this you would in due course see the holy gates open to reveal the Holy Table, the altar. Towards this Omega all things are moving, and from it also flows the river of life out into the world.

A screen with the Beautiful Gates open, with a glimpse of the Holy Table. Church of the Holy Fathers, Shrewsbury, UK. Iconscreen, icons and Holy Table by Aidan Hart.

But this journey began with the portico. Portico or threshold beauty draws us like the fragrance of a rose towards the rose. This threshold art and culture participates both in the hubbub of daily life and in the liturgical life of the Church. Culture should cultivate the soul in preparation for the seed of God’s word.

(to be continued in pt. 2)

————————————-

[1] Maximus the Confessor, Ambigua 41.91, translation from Maximus the Confessor, Selected Writings, trans. G. C. Berthold (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1985).

[2] See for example his writings: The Rape of Man and Nature: An Enquiry into the Origins and Consequences of Modern Science. Ipswich: Golgonooza, 1987; in the USA, published as The Eclipse of Man and Nature: An Enquiry into the Origins and Consequences of Modern Science. West Stockbridge, MA: Lindisfarne Press; Rochester, Vt.: Distributed by Inner Traditions, 1987. Also, The Sacred in Life and Art. Ipswich, U.K.: Golgonooza, 1990. Human Image: World Image: The Death and Resurrection of Sacred Cosmology. Ipswich, U.K.: Golgonooza (in association with Friends of the Centre), 1992; Evia, Greece: Denise Harvey (Publisher), 2004.

[3] Maximus the Confessor, First Century of Various Texts, 92. Trans. From The Philokalia, compiled by Nikodemus of the Holy Mountain and Makarios of Corinth, vol. 2, trans. G. E. H. Palmer, P. Sherrard and K. Ware (London: Faber, 1981). Page 185.

[4] V. G. Paleolog, Tineretea lui Brancusi (Bucharest, 1967).

Thank you for making these incredibly beautiful icons available .

Such beauty. Thank you, Aidan Hart.

[…] Part 2: Gallery Art (here for pt.1) […]