Similar Posts

Spyros Papaloukas (1892-1957) was a major Greek painter of the first half of the twentieth century. Almost a legend for some, he was an innovator of Greek landscape painting. Although not mainly a church iconographer, he holds a very particular position alongside Photis Kontoglou in contemporary liturgical arts. He was born in 1892, started painting at an early age as an apprentice to a local icon painter, and in 1909 was accepted at the School of Fine Arts. From 1916 to 1921 he studied in Paris at the Académie Julien. He died in 1957 at the age of 65, only a year after he was appointed Professor at the School of Fine Arts.

He belongs to the so called “generation of the 30s” – a generation of artists, writers, and other intellectuals that have shaped the development of modern Greek art. (including also Tsarouchis, Kontoglou, Engonopoulos, to name only a few painters). Most of them had visited or had studied in Europe, mainly Paris, and in their quest to achieve a Greek modernity they turned for inspiration to the past and especially Byzantine and folk art in order to define and explore the ‘Greekness’ of Greek art.

It is well known that Photis Kontoglou is considered the major force behind the revival of the liturgical arts in twentieth-century Greece, and more generally the return to Byzantine ways of expression within iconography. It is important to stress the fact that although today many people and artists easily ground their artistic conservatism behind the teachings of Kontoglou, that was not his intent for most of his career. Kontoglou and the rest of the 30’s generation where not turning to the past out of conservativism, but as a step to redefine the path of Greek art. In Kontoglou’s case, this was far more important. He was interested in reviving the orthodox aesthetic that had been heavily compromised by Western naturalistic ways of expression. In this aspect he was a real revolutionary; he managed to overturn the established church painting norms of the time (which was heavily influenced by the so-called ‘Munich painters’) by letting in, a “strong breeze from the east”. It was much later in his career, I believe, that his teachings were over-systematized. This led many of his followers to a stagnant and uninspiring way of painting icons based on mere copying with lack of artistic personality.

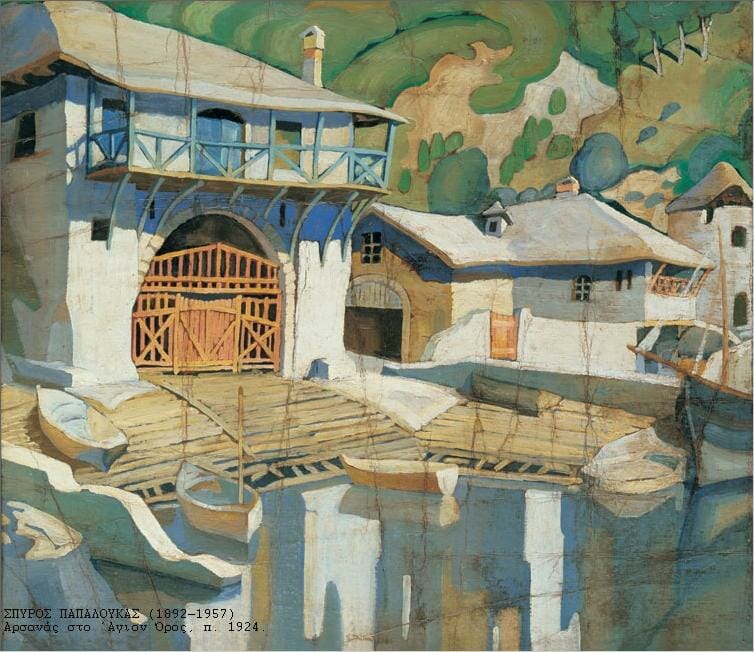

Mount Athos was a major inspiration for the 30s generation, since it was visited by a large number of Greek intellectuals and artists during the first decades of the 20th century. Both Kontoglou and Papaloukas visited Athos and studied the works of Byzantine art there. Kontoglou went there for the first time in 1923 and several times later on. Papaloukas spent a whole year there (November 1923 to November 1924) painting the landscape and copying icons, murals and manuscripts. (See the book: Spyros Papaloukas, the Mount Athos paintings, The Mount Athos Art Archives, 2003).

This sojourn there helped him not only come to terms with Byzantine tradition, but, as he stated during an interview in 1924, “Mount Athos offered true revelations on thousands of my artistic concerns and questions”. There lies the different approach towards Byzantium and tradition that Papaloukas has to offer in comparison to Kontoglou and his followers. Spyros Papaloukas saw in Byzantine art elements that were critical to the modern art movement and in many cases realized that solutions to artistic problems posed by his contemporaries were to be found in Byzantium. In several cases these gave him the answers to formal problems that were vital to painters of his time. Flatness and the adherence to the two-dimensional character of a painting, the possibility of the coexistence of multiple view points, the vital part that color played as an expressive and not merely descriptive element – all these were characteristics that modern painting shared with Byzantine art. This has been noticed even by modern painters whose art had no obvious religious focus such as Malevich and the other Russian avant-gardes, or like Henri Matisse. Matisse made a statement very much in accordance to Papaloukas, about 20 years later, in 1947, when he confronted for the first time Byzantine icons on his trip to Russia: “It was before the icons in Moscow, that this art touched me and I understood Byzantine painting. You surrender yourself that much better when you see your efforts confirmed by such an ancient tradition. It helps you jump the ditch.”

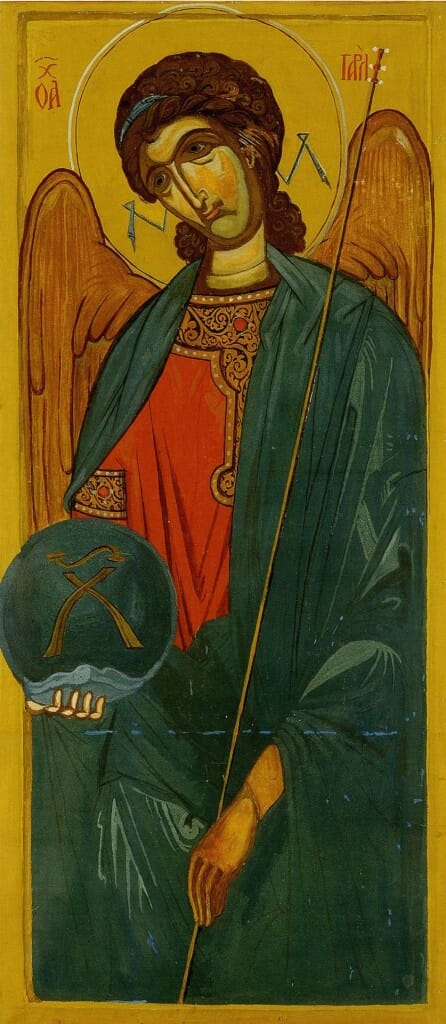

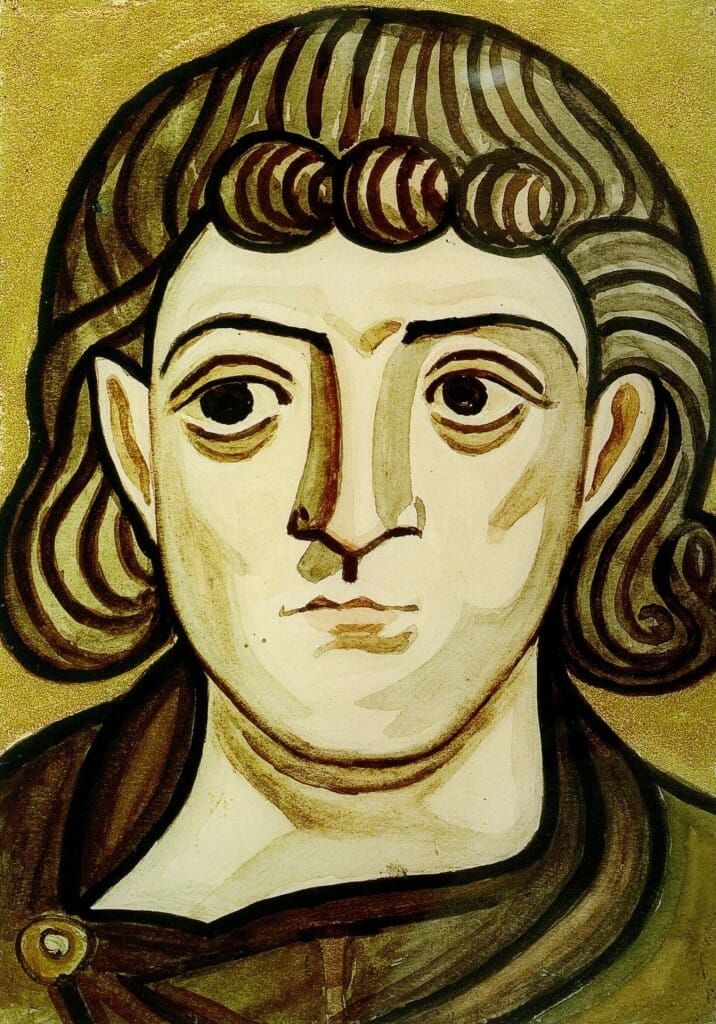

Spyros Papaloukas made several studies and copies of murals and manuscripts while visiting Athos as well as copies of mosaics from the Hosios Loukas church in Boeotia. Even from such copies, one can recognize his effort to see them from a different angle, very close to the rest of his painting, emphasizing the two-dimensionality of Byzantine art and the flatness in color.

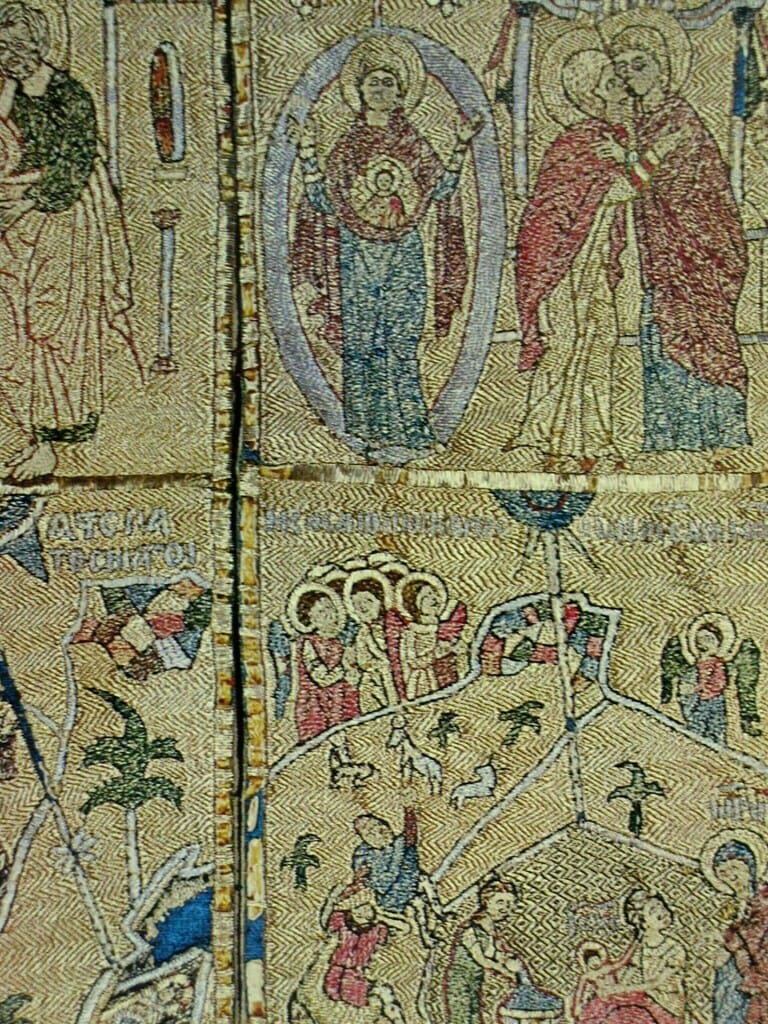

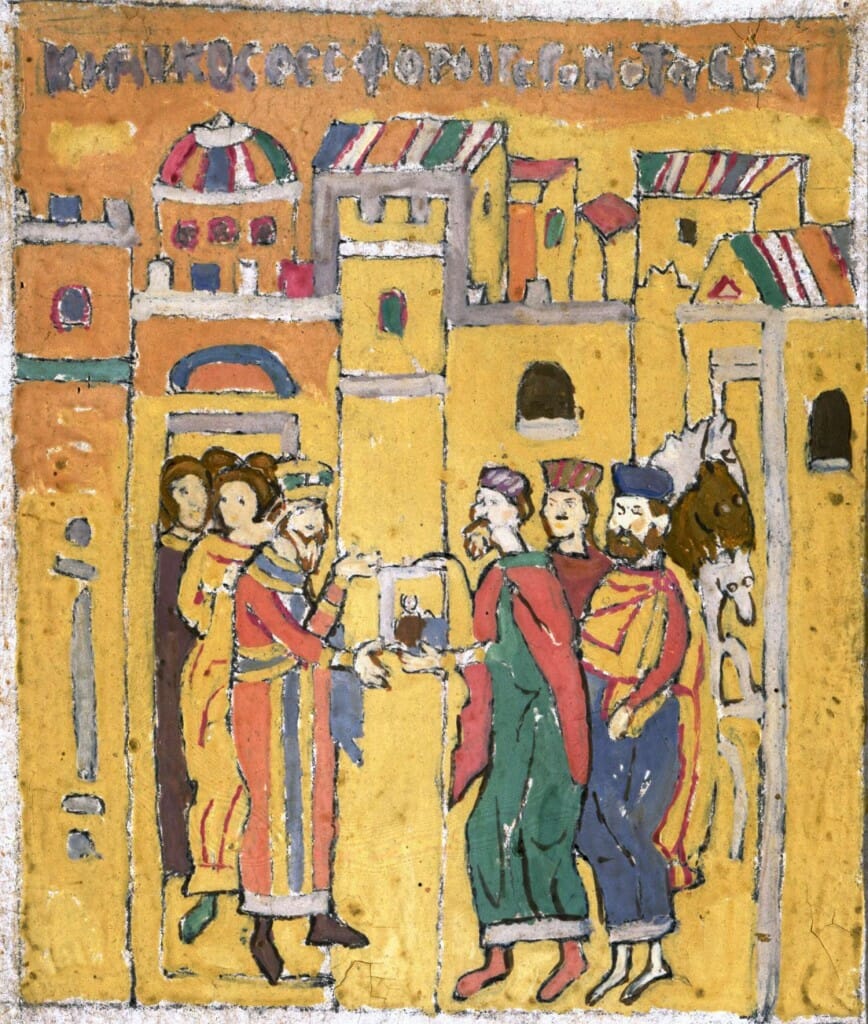

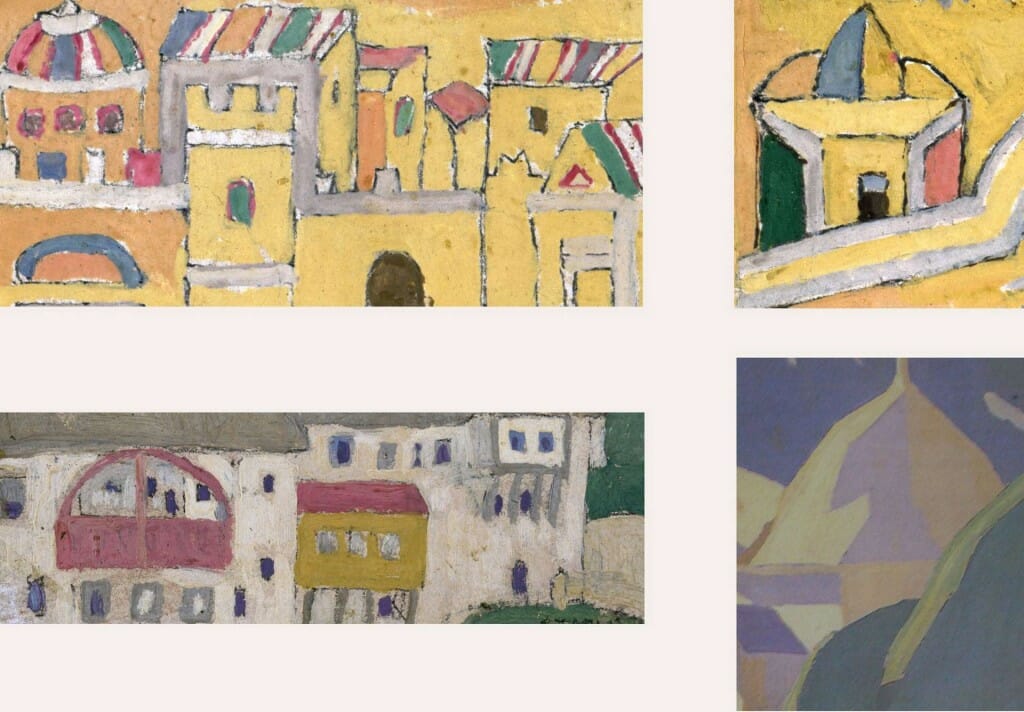

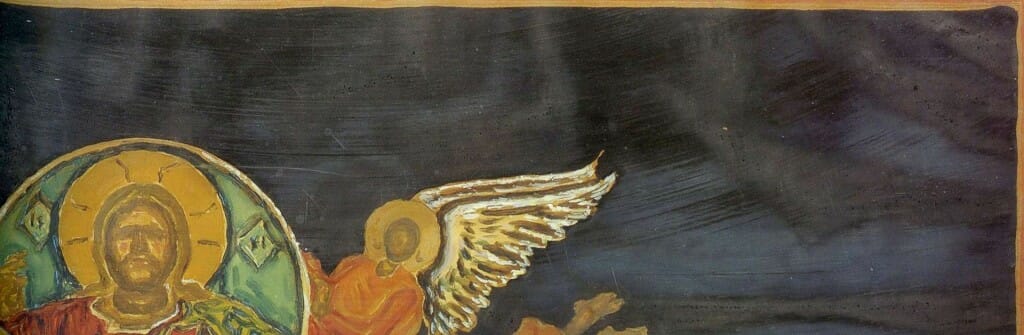

While on Athos, Papaloukas made a complete series of the stances of the Akathist hymn by copying embroidered details from a Byzantine stole (epitracheilion) at Stavronikita monastery. By choosing to work from an embroidery to produce paintings he had more opportunity to create in total freedom towards a very personal style. Examples of this series are the following three photographs.

If one looks at details of these works he will see the obvious resemblance to the original stole but at the same time the relation to his own landscape paintings from Athos. His concern was to create a unique visual vocabulary for all his painting efforts.

A comparison of a landscape detail by Papaloukas and a detail from his iconography at the Amphissa Cathedral provides another example of how close his painting style was to Byzantine art. It also provides an argument regarding the differentiation between religious and profane art; a differentiation that I believe to be totally misleading and false, especially if based only on formal or stylistic characteristics.

Papaloukas had two major experiences in his painting arsenal: one, his sojourn in Paris were he came into contact with the work of the Fauves, the Nabis, and the cubists; the other, his year-long stay on Mount Athos. Using these two starting points he undertook to decorate the Metropolis at Amphissa (1927-1932). This is his major completed contribution to the ecclesiastical and religious painting of contemporary Greece. He also started working on the decoration of the Nomikos School chapel as well as for the monastery of Megalo Spileo, between 1937 and 1939. For these two he executed studies and drawings but never managed to complete the commission due to the outbreak of World War II. Few preliminary drawings also survive from another project, the decoration of the Old Episkopi church of Tegea.

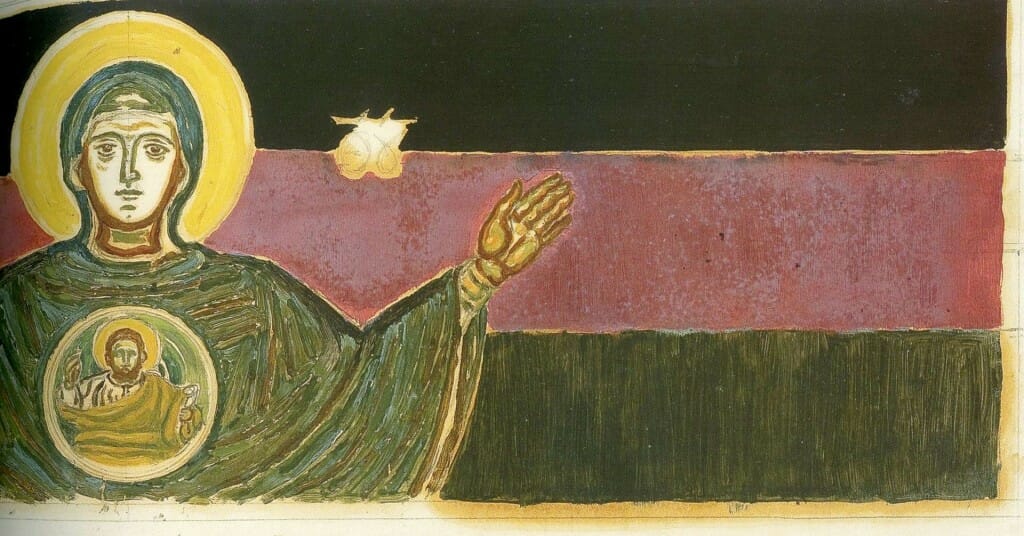

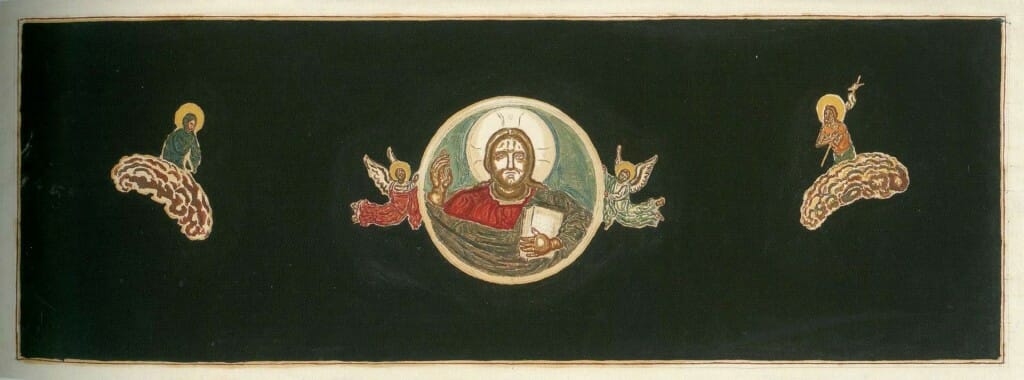

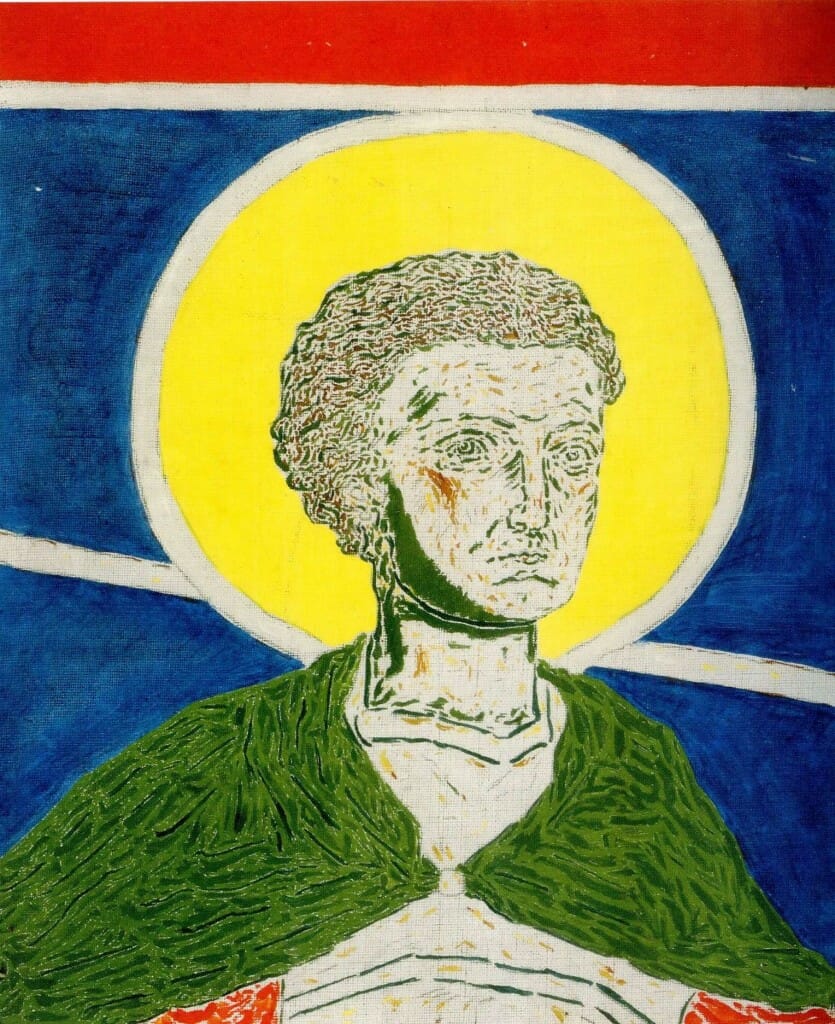

His work for the Nomikos school chapel only went as far as studies and plans, some examples of which are shown in the following photographs. These studies are works much bolder and significantly more abstracted that what he achieved in Amphissa – especially the treatment of backgrounds is almost of a quality reminiscent of abstract painters like Rothko.

Papaloukas was not the kind of painter that would establish his own style and continue with it for life. He was always searching for new expressions without sacrificing the underlying beliefs of his art; his motto was that painting should address the viewer mainly through its material elements. He often used to rework older paintings and create new variations of the same subject matter; he did this with his numerous landscape studies on Mt. Athos by reworking them in a simpler style and on a different scale many years later. On reworking the mural of the Annunciation from the Amphissa Cathedral, he came up with a small watercolor work which is very close to the way he then painted landscapes. Perhaps this simpler and very luminous style might have something to do with his ideas for the church at Tegea.

Since Papaloukas has executed full iconography for really one church only, namely the Amphissa Cathedral, some more information on his religious aesthetics can be derived from the surviving drawings, studies, and the numerous “anthivola” (actual size drawings) for Amphissa. These are now kept in a collection adjacent to the Cathedral. Some of the drawings are fairly straightforward studies (like the cartoon for St.Ephraim the Syrian), while others are more innovative with a technique based on linear or pointillist-like use of crayons or brushes – very characteristic of his style during the later years of his career.

Thank you! His landscapes of sacred places are so beautiful!

Thank you Mr. Kampanis for a wonderful article! Thank you for bringing worthy Spyros Papaloukas to our attention.

Thank you for this thoughtful and informative article. The illustrations are beautiful and to the point.